Prosecution history disclaimer dooms infringement case for patentee

| November 22, 2021

Traxcell Technologies, LLC v. Nokia Solutions and Networks

Decided on October 12, 2021

Prost, O’Malley, and Stoll (opinion by Prost)

Summary

Patentee’s arguments during prosecution distinguishing the claimed invention over prior art were found to be clear and unmistakable disclaimer of certain meanings of the disputed claim terms. The prosecution history disclaimer resulted in claim constructions that favored the accused infringer and compelled a determination of non-infringement.

Details

Traxcell Technologies LLC specializes in navigation technologies. The company was founded by Mark Reed, who is also the sole inventor behind U.S. Patent Nos. 8,977,284, 9,510,320, and 9,642,024 that Traxcell accused Nokia of infringing.

The 284, 320, and 024 patents are directly related to each other as grandparent, parent, and child, respectively. The three patents are concerned with self-optimizing wireless network technology. Specifically, the patents claim systems and methods for measuring the performance and location of a wireless device (for example, a phone), in order to make “corrective actions” to or tune a wireless network to improve communications between the wireless device and the network.

The asserted claims from the three patents require a “first computer” (or in some of the asserted claims, simply “computer”) that is configured to perform several functions related to the “location” of a mobile wireless device.

Central to the parties’ dispute was the proper constructions of “first computer” and “location”.

Nokia’s accused geolocation system was undisputedly a self-optimizing network product. Nokia’s system performed similar functions as those claimed in the asserted computers, but across multiple computers. Nokia’s system also collected performance information for mobile wireless devices located within 50-meter-by-50-meter grids.

To avoid infringement, Nokia argued that the claimed “first computer” required a single computer performing the claimed functions, and that the claimed “location” required more than the use of a grid.

On the other hand, wanting to capture Nokia’s products, Traxcell argued that the claimed “first computer” encompassed embodiments in which the claimed functions were spread among multiple computers, and that the claimed “location” plainly included a grid-based location.

Unfortunately for Traxcell, their arguments did not stand a chance against the prosecution histories of the asserted patents.

The doctrine of prosecution history disclaimer “preclud[es] patentees from recapturing through claim interpretation specific meanings disclaimed during prosecution”. Omega Eng’g, Inc. v. Raytek Corp., 334 F.3d 1314, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2003). “Prosecution disclaimer can arise from both claim amendments and arguments”. SpeedTrack, Inc. v. Amazon.com, 998 F.3d 1373, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2021). “An applicant’s argument that a prior art reference is distinguishable on a particular ground can serve as a disclaimer of claim scope even if the applicant distinguishes the reference on other grounds as well”. Id. at 1380. For there to be disclaimer, the patentee must have “clearly and unmistakably” disavowed a certain meaning of the claim.

Of the three asserted patents, the 284 patent had the most protracted prosecution, with six rounds of rejections. And it was the prosecution history of the 284 patent that provided the fodder for the district court’s claim constructions. Incidentally, the 284 patent was also the only one of the three asserted patents prosecuted by the inventor, Mark Reed, himself.

During claim construction, the district court construed the terms “first computer” and “computer” to mean a single computer that could performed the various claimed functions.

The district court first looked to the plain language of the claims. The claim language recites “a first computer” or “a computer” that performs a function, and then recites that “the first computer” or “the computer” performs several additional functions. The district court determined that the claims plainly tied the claimed functions to a single computer, and that “it would defy the concept of antecedent basis” for the claims to refer back to “the first computer” or “the computer”, if the corresponding tasks were actually performed by a different computer.

The intrinsic evidence that convinced the district court of its claim construction was, however, the prosecution history of the 284 patent.

During prosecution, in a 67-page response, Mr. Reed argued explicitly and at length, in a section titled “Single computer needed in Reed et al. [i.e., the pending application] v. additional software needed in Andersson et al. [i.e., the prior art]”, that the claimed invention requiring just one computer distinguished over the prior art system using multiple computers. The district court quoted extensively from this response as intrinsic evidence supporting its claim construction.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s claim construction, quoting still more passages from the same response as evidence that the patentee “clearly and unmistakably disclaimed the use of multiple computers”.

Next, the district court addressed the term “location”. The district court construed the term to mean a “location that is not merely a position in a grid pattern”.

Here, the district court’s claim construction relied almost exclusively on arguments that Reed made during prosecution of the 284 patent. Referring again to the same 67-page response, the district court noted that Mr. Reed explicitly argued, in a section titled “Grid pattern not required in Reed et al. v. grid pattern required in Steer et al.”, that the claimed invention distinguished over the prior art because the claimed invention operated without the limitation of a grid pattern, and that the absence of a grid pattern permitted finer tuning of the network system.

And again, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s claim construction, finding that “the disclaimer here was clear and unmistakable”.

The claim constructions favored Nokia’s non-infringement arguments that its system lacked the single-computer, non-grid-pattern-based-location limitations of the asserted claims. Accordingly, the district court found, and the Federal Circuit affirmed, that Nokia’s system did not infringe the 284, 320, and 024 patents.

Traxcell made an interesting argument on appeal—specifically, the disclaimer found by the district court was too broad and a narrower disclaimer would have been enough to overcome the prior art. Traxcell seemed to be borrowing from the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel. Under that doctrine, arguments or amendments made during prosecution to obtain allowance of a patent creates prosecution history estoppel that limits the range of equivalents available under the doctrine of equivalents.

However, the Federal Circuit was unsympathetic to Traxcell’s argument, explaining that Traxcell was held “to the actual arguments made, not the arguments that could have been made”. The Federal Circuit also noted that “it frequently happens that patentees surrender more…than may have been absolutely necessary to avoid particular prior art”.

Mr. Reed’s somewhat unsophisticated prosecution of the 284 patent was in sharp contrast to the prosecution of the related 320 and 024 patents, which were handled by a patent attorney. The prosecution histories of the 320 and 024 patents said very little about the cited prior art, even less about the claimed invention. In addition, whereas Mr. Reed editorialized on various claimed features during prosecution of the 284 patent, the prosecution histories of the 320 and 024 patents rarely even paraphrased the claims.

Takeaways

- Avoid gratuitous remarks that define or characterize the claimed invention or the prior art during prosecution. Quote the claim language directly and avoid paraphrasing the claim language, as the paraphrases risk being construed later as a narrowing characterization of the claimed invention.

- Avoid claim amendments that are not necessary to distinguish over the prior art.

- The prosecution history of a patent can affect the construction of claims in other patents in the same family, even when the claim language is not identical. Be mindful about how arguments and/or amendments made in one application may be used against other related applications.

DESIGN CLAIM IS LIMITED TO AN ARTICLE OF MANUFACTURE IDENTIFIED IN THE CLAIM

| November 8, 2021

In Re: Surgisil, L.L.P., Peter Raphael, Scott Harris

Decided on October 4, 2021

Moore (author), Newman, and O’Malley

Summary:

The Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB’s anticipation decision on a claim of SurgiSil’s ’550 application because a design claim should be limited to an article of manufacture identified in the claim. The Federal Circuit held that since the claim in the ’550 application identified a lip implant, the claim is limited to lip implants and does not cover other article of manufacture. The CAFC held that since the Blick reference discloses an art tool rather than a lip implant, the PTAB’s anticipation finding is not correct.

Details:

The ’550 application

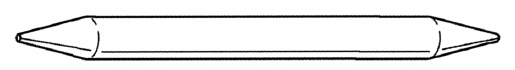

SurgiSil’s ’550 application claims an ornamental design for a lip implant[1] as shown below:

The examiner rejected a claim of the ’550 application as being anticipated by Blick, which discloses an art tool called stump as shown below:

The PTAB

The PTAB affirmed the examiner’s decision and found that the differences between the claimed design in the ’550 application and Blick are minor.

The PTAB rejected SurgiSil’s argument that Blick discloses a “very different” article of manufacture than a lip implant reasoning that “it is appropriate to ignore the identification of manufacture in the claim language” and “whether a reference is analogous art is irrelevant to whether that reference anticipates.”

The Federal Circuit

The CAFC reviewed the PTAB’s legal conclusion that the article of manufacture identified in the claims is not limiting de novo. The CAFC ultimately held that the PTAB erred as a matter of law.

By citing 35 U.S.C. §171(a) (“Whoever invents any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.”), the CAFC held that a design claim is limited to the article of manufacture identified in the claim.

The CAFC also cited a case called Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc., 938 F.3d 1334, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2019)[2] and the MPEP to hold that the claim at issue should be limited to the particular article of manufacture identified in the claim.

The CAFC held that since the claim identified a lip implant, the claim is limited to lip implants and does not cover other article of manufacture.

The CAFC held that since Blick discloses an art tool rather than a lip implant, the PTAB’s anticipation finding is not correct.

Therefore, the CAFC reversed the PTAB’s decision.

Takeaway:

- It would certainly be easier to obtain design patents going forward. Can Applicant obtain design patents by using a known design in the art and applying to a new article of manufacture?

- It would be difficult to invalidate design patents because prior arts from a different article of manufacture could not be used to invalidate them.

- Applicant should be careful to amend a title/claim and provide any description on title/terms in the claim in a design application because they could be used to construe an article of manufacture and to clarify the scope of a design patent claim.

- It may be difficult to enforce the design patent for a certain article of manufacture (i.e., “lip implant”) against a different article of manufacture (“art stump”).

[1] Website for SurgiSil: SurgiSil’s silicone lip implants are an alternative to “repetitive, costly, and painful filler injections,” but that they can be removed at any time.

[2] In this case, the CAFC held that a particular claim was limited to a wicker pattern applied to an article of manufacture recited in the claim (chair) and did not cover the use of the same pattern on another non-claimed article (i.e., basket).