Revisiting KSR: “A person of ordinary skill is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton.”

| June 29, 2021

Becton, Dickinson and Company v. Baxter Corporation Englewood

Decided on May 28, 2021

Prost*, Clevenger, and Dyk. Court opinion by Dyk. (*Sharon Prost vacated the position of Chief Judge on May 21, 2021, and Kimberly A. Moore assumed the position of Chief Judge on May 22, 2021.)

Summary

On appeals from the United States Patent and Trademark Office, Patent Trial and Appeal Board in an inter partes review, the Federal Circuit unanimously revered the Board’s conclusion of non-obviousness of an asserted patent, directed to a “method for performing telepharmacy,” and a “system for preparing and managing patient-specific dose orders that have been entered into a first system.” The Federal Circuit stated that, in analysis of obviousness, a person of ordinary skill would also consider a source other than cited prior art references, and established that cancellation of all the claims of a patent does not affect the status of the patent as pre-AIA Section 102(e)(2) reference.

Details

I. Background

Becton, Dickinson and Company (“Becton”) petitioned for inter partes review of claims 1– 13 and 22 of U.S. Patent No. 8,554,579 (“the ’579 patent”), owned by Baxter Corporation Englewood (“Baxter”).

Becton asserted invalidity of the challenged claims primarily based on three prior art references: U.S. Patent No. 8,374,887 (“Alexander”), U.S. Patent No. 6,581,798 (“Liff”), and U.S. Patent Publication No. 2005/0080651 (“Morrison”).

Claims 1 and 8 are illustrative of the ’579 patent, as agreed by the parties. Claim 1 is directed to a “method for performing telepharmacy,” and claim 8 is directed to a “system for preparing and managing patient-specific dose orders that have been entered into a first system.”

There are two contested limitations on appeal: the “verification” limitation in claim 8, and the “highlighting” limitation in claims 1 and 8. Claim 8 recites three elements, an order processing server, a dose preparation station, and a display. The relevant portion of the dose preparation station in claim 8, containing both limitations, reads:

8. A system for preparing and managing patient-specific dose orders that have been entered into a first system, comprising:

a dose preparation station for preparing a plurality of doses based on received dose orders, the dose preparation station being in bi-directional communication with the order processing server and having an interface for providing an operator with a protocol associated with each received drug order and specifying a set of drug preparation steps to fill the drug order, the dose preparation station including an interactive screen that includes prompts that can be highlighted by an operator to receive additional information relative to one particular step and includes areas for entering an input;

. . . and wherein each of the steps must be verified as being properly completed before the operator can continue with the other steps of drug preparation process, the captured image displaying a result of a discrete isolated event performed in accordance with one drug preparation step, wherein verifying the steps includes reviewing all of the discrete images in the data record . . . .

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) determined that asserted claims were not invalid as obvious. While the Board found that Becton had established that one of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to combine Alexander and Liff, as well as Alexander, Liff, and Morrison, and that Baxter’s evidence of secondary considerations was weak, the Board nevertheless determined that Alexander did not teach or render obvious the verification limitation and that combinations of Alexander, Liff, and Morrison did not teach or render obvious the highlighting limitation.

Becton appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) unanimously revered the Board’s conclusion of non-obviousness because the determination regarding the verification and highlighting limitations is not supported by substantial evidence.

(i) The Verification Limitation

Alexander discloses in a relevant part: “[I]n some embodiments, a remote pharmacist may supervise pharmacy work as it is being performed. For example, in one embodiment, a remote pharmacist may verify each step as it is performed and may provide an indication to a non-pharmacist per- forming the pharmacy that the step was performed correctly. In such an example, the remote pharmacist may provide verification feedback via the same collaboration software, or via another method, such as by telephone.” Alexander, col. 9 ll. 47–54 (emphasis added).

Relying on the above-cited portion of Alexander, the Board found persuasive Baxter’s argument that Alexander “only discusses that ‘a remote pharmacist may verify each step’; not that the remote pharmacist must verify each and every step before the operator is allowed to proceed” (emphasis added).

The Court concluded that the Board’s determination that Alexander does not teach the verification limitation is not supported by substantial evidence because, among other things, the Court found it quite clear that “[i]n the context of Alexander, “may” does not mean “occasionally,” but rather that one “may” choose to systematically check each step.”

(ii) The Highlighting Limitation

Becton did not argue that Liff “directly discloses highlighting to receive additional language about a drug preparation step.” Instead, Becton argued that “Liff discloses basic computer functionality—i.e., using prompts that can be highlighted by the operator to receive additional information—that would render the highlighting limitation obvious when applied in combination with other references,” primarily Alexander.

In support of petition for inter partes review, Dr. Young testified in his declaration that Liff “teaches that the user can highlight various inputs and information displayed on the screen, as illustrated in Figure 14F.”

The Board found that Liff taught “highlight[ing] patient characteristics when dispensing a prepackaged medication.” Baxter did not contend that this aspect of the Board’s decision was erroneous.

Nevertheless, while finding that “this present[ed] a close case,” the Board determined, that “Dr. Young fail[ed] to explain why Liff’s teaching to highlight patient characteristics when dispensing a prepackaged medication would lead one of ordinary skill to highlight prompts in a drug formulation context to receive additional information relative to one particular step in that process, or even what additional information might be relevant.” In addition, the Board found that Becton’s arguments with respect to Morrison did not address the deficiency in its position based on Alexander and Liff.

In contrast, citing KSR (“[a] person of ordinary skill is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton”), the Court concluded that the Board erred in looking to Liff as the only source a person of ordinary skill would consider for what “additional information might be relevant.” The Court reached an opposite conclusion by citing following Dr. Young’s testimony:

“[a] person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood that additional information could be displayed on the tabs taught by Liff” and that “such information could have included the text of the order itself, information relating to who or how the order should be prepared, or where the or- der should be dispensed.”

“[a] medication dose order for compounding a pharmaceutical would have been accompanied by directions for how the dose should be prepared, including step-by-step directions for preparing the dose.”

(iii) An Alternative Ground

As an alternative ground to affirm the Board’s determination of non-obviousness, Baxter argues that the Board erred in determining that Alexander is prior art under 35 U.S.C. § 102(e)(2) (pre-AIA).

It is undisputed that the filing date of the application for Alexander is February 11, 2005, which is before the earliest filing date of the application for the ’579 patent, October 13, 2008; that the Alexander claims were granted; and that the application for Alexander was filed by another.

However, based on the fact that all claims in Alexander (granted on February 12, 2013) were cancelled on February 15, 2018, following inter partes review, Baxter argued that “because the Alexander ‘grant’ had been revoked, it can no longer qualify as a patent ‘granted’ as required for prior art status under Section 102(e)(2).”

The Court rejected Baxter’s argument because “[t]he text of the statute requires only that the patent be “granted,” meaning the “grant[]” has occurred. 35 U.S.C. § 102(e)(2) (pre-AIA)” and “[t]he statute [thus] does not require that the patent be currently valid.”

(iv) Secondary Considerations

The Court rejected Baxter’s argument because “Baxter does not meaningfully argue that the weak showing of secondary considerations here could overcome the showing of obviousness based on the prior art.”

Takeaway

· In analysis of obviousness, a person of ordinary skill would also consider a source other than cited prior art references (petitioner’s testimony in this case).

· Cancellation of all the claims of a patent does not affect the status of the patent as pre-AIA Section 102(e)(2) reference.

No likelihood of confusion with the mark BLUE INDUSTRY and opposer’s numerous marks having INDUSTRY as an element

| June 25, 2021

Pure & Simple Concepts, Inc. v. I H W Management Limited, DBA Finchley Group (non-precedential)

Decided on May 24, 2021

Moore, Reyna, Chen (opinion by Reyna)

Summary

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“the CAFC”) affirmed the Board’s determination of no likelihood of confusion or dilution between numerous marks of Pure & Simple Concepts, Inc. (hereinafter “P&S”) having the shared term “INDUSTRY” and “BLUE INDUSTRY” mark of I H W Management Limited, d/b/a The Finchley Group (hereinafter “Fincley”).

Details

P&S owns eight registered trademarks which all use the word “INDUSTRY” and licenses the use of these marks in connection with apparel items. On April 30, 2015, Finchley filed an application to register the mark BLUE INDUSTRY for various clothing items. P&S opposed registration of Finchley’s mark under Section 2(d) and 43(c) of the Lanham Act on the grounds of likelihood of confusion and likelihood of dilution by blurring based on P&S’s previous use and registration of its numerous INDUSTRY marks. The Board dismissed the opposition, finding that P&S failed to prove a likelihood of confusion, and that P&S failed to establish the critical element of fame for dilution.

P&S appealed to the CAFC, contending that the Board erred by (1) not considering all relevant DuPont factors; (2) determining the word “BLUE” to be the dominant term in Finchley’s mark; (3) relying heavily on third-party registrations; and (4) failing to find P&S’s family of marks as being famous.

First, in arguing that the Board erred by not considering all relevant DuPont factors, P&S contended that the Board did not consider that clothing items are more likely to be purchased on an impulse, and therefore, consumers are more likely to be confused. Finchley argued that this argument concerns the DuPont factor 4, which P&S presented no evidence before the Board. The CAFC agreed with Finchley, finding that P&S failed to present the evidence, and accordingly, P&S forfeited argument as to this factor.

Next, P&S contended that the Board erred in concluding that “BLUE” is the dominant term in the commercial impression created by Finchley’s mark. While it is not proper to dissect a mark, “one feature of a mark may be more significant than other features, and [thus] it is proper to give greater force and effect to that dominant feature.” Giant Food, Inc. v. Nation’s Foodservice, Inc., 710 F.2d 1565, 1570 (Fed. Cir. 1983). P&S cited as an example, Trump v. Caesars World, Inc., 645 F. Supp. 1015, 1019 (D.N.J. 1986), where the second word, “Palace,” was found to be dominant in the marks TRUMP PALACE and CEASER’S PALACE. However, the CAFC determined that the Board’s finding that BLUE to be the lead term in Finchley’s mark, and that the term BLUE is most likely to be impressed upon the minds of the purchasers and be remembered was supported by substantial evidence.

Third, P&S argued that the Board erred by heavily relying on third-party registrations. P&S argued that some of these third-party registrations were listed twice, some were canceled, some had no evidence of use, and some listed different goods. Nevertheless, the CAFC affirmed that the term “INDUSTRY,” or the plural thereof, has been registered by numerous third parties to identify clothing and apparel items, and therefore, the term is weak, and the scope is limited as applied to clothing items.

Finally, as to P&S’s dilution claim, the Board determined that the number of registered marks by third parties having the INDUSTRY element precluded a finding that P&S owns a family of marks for the shared INDUSTRY element. In addition, the evidence presented by P&S was insufficient to prove that the marks were famous. The CAFC agreed with the Board’s finding of P&S’s dilution claim.

The CAFC found the Board’s findings are supported by substantial evidence, and the Board correctly found there was no likelihood of confusion of dilution.

Takeaway

- Certain portions of a mark can be determined as being dominant.

- Third party registrations are relevant in proving weakness of certain portions of a mark.

Tags: Dilution > Likelihood of Confusion under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d) > Trademark

Making DJ Jurisdiction Easier to Maintain

| June 22, 2021

Trimble Inc. v. PerDiemCo LLC

Decided on May 12, 2021

Opinion by: Dyk, Newman, and Hughes

Summary:

How many letters, emails, and/or telephone calls from an out-of-state patent owner to an alleged patent infringer does it take to establish specific personal jurisdiction over that out-of-state patent owner in the alleged infringer’s home state? Somewhere between 3 and 22, depending on the nature of those communications.

Procedural History:

Trimble and Innovative Software Engineering (ISE) filed a lawsuit in its home state (California), seeking declaratory judgment that it doesn’t infringe out-of-state (Texas) PerDiemCo’s patents. The district court dismissed the case for lack of specific personal jurisdiction over PerDiemCo, relying on Red Wing Shoe Co. v. Hockerson-Halberstadt, Inc., 148 F.3d 1355, 1361 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (“[a] patentee should not subject itself to personal jurisdiction in a forum solely by informing a party who happens to be located there of suspected infringement” because “[g]rounding personal jurisdiction on such contacts alone would not comport with principles of fairness.”). The Federal Circuit reversed, finding specific personal jurisdiction.

Background:

PerDiemCo is a Texas LLC owning eleven geofencing patents monitoring a vehicle’s entry or exit from a preset area, electronically logging hours and activities of the vehicle’s driver. PerDiemCo’s sole owner, officer, and employee is Robert Babayi, a patent attorney living and working in Washington, DC, who rents office space in Marshall, Texas, that had never been visited.

Trimble is incorporated in Delaware and headquartered in Sunnyvale, CA. ISE is a wholly owned subsidiary LLC of Trimble, headquartered in Iowa.

Mr. Babayi sent a letter to ISE in Iowa offering a nonexclusive license and including an unfiled patent infringement complaint for the Northern District of Iowa and a claim chart detailing the alleged infringement. ISE forwarded that letter to Trimble’s Chief IP Counsel in Colorado, who was the point of contact for this matter. Mr. Babayi communicated “at least twenty-two times” by letter, email, and telephone calls with Trimble’s IP Counsel in Colorado, to negotiate and to further substantiate infringement allegations, including Trimble’s products, more patents, and more claim charts. PerDiemCo also threatened to sue in the Eastern District of Texas, identifying local counsel.

Personal Jurisdiction Primers:

- PerDiemCo’s communications with Trimble’s IP Counsel in Colorado are considered, for personal jurisdiction, purposefully directed to the company at its headquarters (in California), not to the location of counsel. See, Maxchief Investments Ltd. v. Wok & Pan, Ind., Inc., 909 F.3d 1134, 1139 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

- “[A] tribunal’s authority [to exercise personal jurisdiction over a defendant] depends on the defendant’s having such ‘contacts’ with the forum State that ‘the maintenance of the suit’ is ‘reasonable, in the context of our federal system of government,’ and ‘does not offend traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.’” “The contacts needed for [specific] jurisdiction often go by the name ‘purposeful availment.’” Ford Motor Co. v. Mont. Eighth Jud. Dist. Ct., 141 S. Ct. 1017, 1024 (2021) (quoting Int’l Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310, 316-317 (1945)).

- From Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462 (1985) and World-Wide Volkswagon Corp. v. Woodson, 444 U.S. 286 (1980), courts determine whether the exercise of jurisdiction would “comport with fair play and substantial justice” by considering five factors: (1) the burden on the defendant; (2) the forum State’s interest in adjudicating the dispute; (3) the plaintiff’s interest in obtaining convenient and effective relief; (4) the interstate judicial system’s interest in obtaining the most efficient resolution of controversies; and (5) the shared interest of the several States in furthering fundamental substantive social policies.

Decision:

In Red Wing, a cease-and-desist letter was deemed “more closely akin to an offer for settlement of a disputed claim rather than an arms-length negotiation in anticipation of a long-term continuing business relationship.” Accordingly, in Red Wing, this court held that “[p]rinciples of fair play and substantial justice afford a patentee sufficient latitude to inform others of its patent rights without subjecting itself to jurisdiction in a foreign forum.” However, this year’s Supreme Court Ford decision and other post-Red Wing Supreme Court decisions have emphasized that “analysis of personal jurisdiction cannot rest on special patent policies.”

Repeated communications stent into a state may create specific personal jurisdiction, depending on the nature and scope of such communications. Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S 298, 308 (1992). And, the out-of-state defendant’s “negotiation efforts, although accomplished through telephone and mail, can still be considered as activities ‘purposefully directed’ at residents of [the forum].” Inamed Corp. v. Kuzmak, 249 F.3d 1356, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (applying Quill). Personal jurisdiction was held to be reasonable after the out-of-state defendant sent communications to eleven banks located in the forum state identifying patents, alleging infringement, and offering non-exclusive licenses, rejecting Red Wing and its progeny as having created a rule that “the proposition that patent enforcement letters can never provide the basis for jurisdiction in a declaratory judgment action.” Jack Henry & Associates, Inc. v. Plano Encryption Technologies LLC, 910 F.3d 1199, 1201, 1206 (Fed. Cir. 2018); see also, Genetic Veterinary Sciences, Inc. v. Laboklin, GmbH & Co. KG, 933 F.3d 1302, 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

Beyond the sending of communications into a forum, DJ jurisdiction can also be premised on other contacts, such as “hiring an attorney or patent agent in the forum state to prosecute a patent application that leads to the asserted patent, see Elecs. for Imaging, Inc. v. Coyle, 340 F.3d 1344, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2003); physically entering the forum to demonstrate the technology underlying the patent to the eventual plaintiff, id., or to discuss infringement contentions with the eventual plaintiff, Xilinx, Inc. v. Papst Licensing GmbH & Co. KG, 848 F.3d 1346, 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2017); the presence of ‘an exclusive licensee … doing business in the forum state,’ Brekenridge Pharm., Inc. v. Metabolite Labs., Inc., 444 F.3d 1356, 1366-67 (Fed. Cir. 2006); and ‘extra-judicial patent enforcement’ targeting business activities in the forum state, Campbell Pet Co. v. Miale, 542 F.3d 879, 886 (Fed. Cir. 2008).”

The Supreme Court’s recent Ford decision reinforces “that a broad set of a defendant’s contacts with a forum are relevant to the minimum contacts analysis.” In Ford, personal jurisdiction could be exercised over Ford even though the two types of vehicles involved in the accident were not sold in the forum states. Specific personal jurisdiction simply “demands that the suit ‘arise out of or relate to the defendant’s contacts with the forum.’” So, the broader efforts by Ford in selling similar vehicles and having dealerships in the forum states established specific personal jurisdiction.

Unlike Red Wing, which involved a total of three letters (asserting patent infringement and offering a nonexclusive license), this case involved twenty-two communications, “an extensive number of contacts with the forum in a short period of time [three months].” And unlike Red Wing “solely…informing a party who happens to be located [in the forum state] of suspected infringement,” this case’s communications continually amplified threats of infringement, including continually adding more patents, more products, suggesting mediation to reach a settlement on infringement allegations, and threat of suit in EDTx, identifying counsel that PerDiemCo planned to use. As such, “PerDiemCo’s attempts to extract a license in this case are much more akin to ‘an arms-length negotiation in anticipation of a long-term continuing business relationship’ over which a district court may exercise jurisdiction.”

As for whether specific personal jurisdiction would comport with fair play and substantial justice, the court found no fairness concerns as follows:

- Burden on the defendant: PerDiemCo’s office in Texas is “pretextual” (not an operating company, but merely an IP portfolio owner, with no employees in Texas) and is far from Washington, DC where Mr. Babayi lives and works. So, if Texas is ok, so is California.

- Forum state’s interest in adjudicating the dispute: ND Cal. has significant interest since Trimble is a resident there.

- Plaintiff’s interest in obtaining convenient and effective relief: Trimble is near the federal district court.

- Interstate judicial system’s interest in obtaining the most efficient resolution of controversies: no favor either way.

- The shared interest of the several states in furthering fundamental substantive social polices: not applicable.

Takeaways:

- This case is a good refresher for specific personal jurisdiction in the DJ action arena for patent owners and accused infringers.

- Red Wing is NOT overturned. Quite the contrary, the court quotes from the Supreme Court’s recent Ford decision that treats “isolated or sporadic [contacts] differently from continuous ones,” and confirms that “Red Wing remains correctly decided with respect to the limited number of communications involved in that case.” The court only emphasizes that “there is no general rule that demand letters can never create specific personal jurisdiction.”

- In Red Wing, the patentee’s first letter asserted patent infringement and offered a nonexclusive license. The second letter granted an extension of time for a response and asserted more products as infringing the patent. The third letter rebutted Red Wing’s noninfringement analysis and continued to offer to negotiate a nonexclusive license. So, there was some “amplification” in the second letter, just like in this case. But, the continued back and forth negotiations in Red Wing was much more limited than in this case. Where do we cross the Red Wing threshold and enter into specific personal jurisdiction for a DJ action? It is not as simple as somewhere between 3 and 22. It is the nature of the communications – the continuing of negotiations “to extract a license” that likens the behavior/communications to “an arms-length negotiation in anticipation of a long-term continuing business relationship.”

- From this case, patent owners must be careful to avoid continued communications, whether by letter, email, or telephone, that as a whole can be construed to be a continuation of negotiations to extract a license or “an arms-length negotiation in anticipation of a long-term continuing business relationship.” If the desired nonexclusive license doesn’t look promising after just a handful of contacts, this case suggests that it is safer for the patent owner to hold off further back and forth negotiations and file a complaint in the patent owner’s preferred forum state, otherwise risk a DJ action in the accused infringer’s home court. For the accused infringer, this case suggests that stringing the patent owner out and creating more back and forth communications would help secure specific personal jurisdiction for a DJ action in the accused infringer’s home court.

Tailored Advertising Claims Are Invalidated Due to Lack of Improvements to Computer Functionality

| June 8, 2021

Free Stream Media Corp., DBA Samba Tv, V. Alphonso Inc., Ashish Chordia, Lampros Kalampoukas, Raghu Kodige

Decided on May 11, 2021

Before DYK, REYNA, and HUGHES. Opinion by REYNA.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s decision and found that the asserted claims directed to tailored advertising were patent ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Background

Free Stream sued Alphonso for infringement of its US patents No. 9,026,668 (“the ’668 patent”) and No. 9,386,356 (“the ’356 patent”). The patents describe a system sending tailored advertisements to a mobile phone user based on data gathered from the user’s television. Claim 1 and 10 were involved in the alleged infringement. Free Stream conceded claims 1 and 10 are similar. Listed below is claim 1.

1. A system comprising:

a television to generate a fingerprint data;

a relevancy-matching server to:

match primary data generated from the fingerprint data with targeted data, based on a relevancy factor, and

search a storage for the targeted data;

wherein the primary data is any one of a content identification data and a content identification history;

a mobile device capable of being associated with the television to:

process an embedded object,

constrain an executable environment in a security sandbox, and

execute a sandboxed application in the executable environment; and

a content identification server to:

process the fingerprint data from the television, and

communicate the primary data from the fingerprint data to any of a number of devices with an access to an identification data of at least one of the television and an automatic content identification service of the television.

The asserted claims of ‘356 patent includes three main components: (1) a television (e.g., a smart TV) or a networked device ; (2) a mobile device or a client device ; and (3) a relevancy matching server and a content identification server. The television is a network device collecting primary data, which can consist of program information, location, weather information, or identification information. The mobile phone is a client device that may be smartphones, computers, or other hardware showing advertisements. The client device includes a security sandbox, which is a security mechanism for separating running programs. Finally, the servers use primary data from the networked device to select advertisements or other targeted data based on a relevancy factor associated with the user.

Alphonso argued that the asserted claims are patent ineligible under § 101 because they are directed to the abstract idea of tailored advertising. But Free Stream characterized the claims as directed to a specific improvement of delivering relevant content (e.g., targeted advertising) by bypassing the conventional “security sandbox” separating the mobile phone from the television.

The district court rejected Alphonso’s argument and applied step one of the Alice test to conclude that the asserted claims are not directed to an abstract idea. The district court found that the ’356 patent “describes systems and methods for addressing barriers to certain types of information exchange between various technological devices, e.g., a television and a smartphone or tablet being used in the same place at the same time.”

Discussion

The Federal Circuit agreed with Alphonso’s contention that the district court erred in concluding that the ’356 patent is not directed to patent-ineligible subject matter. Claims 1 and 10 were reviewed by the Federal Circuit as being directed to (1) gathering information about television users’ viewing habits; (2) matching the information with other content (i.e., targeted advertisements) based on relevancy to the television viewer; and (3) sending that content to a second device.

Free Stream contended that claim 1 is “specifically directed to a system wherein a television and a mobile device are intermediated by a content identification server and relevancy-matching server that can deliver to a ‘sandboxed’ mobile device targeted data based on content known to have been displayed on the television, despite the barriers to communication imposed by the sandbox.” Free Stream also asserted that its invention allows devices on the same network to communicate where such devices were previously unable to do so, namely bypassing the sandbox security.

The Federal Circuit, however, noted that the specification does not provide for any other mechanism that can be used to bypass the security sandbox other than “through a cross site scripting technique, an appended header, a same origin policy exception, and/or an other mode of bypassing

a number of access controls of the security sandbox.” Also, the Federal Circuit pointed out that the asserted claims only state the mechanism used to achieve the bypassing communication but not at all describe how that result is achieved.

Further, the Federal Circuit went on to note that “even assuming the specification sufficiently discloses how the sandbox is overcome, the asserted claims nonetheless do not recite an improvement in computer functionality.” The asserted claims do not incorporate any such limitations of bypassing the sandbox. The Federal Circuit determined that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “targeted advertising.”

The Federal Circuit further reached Step 2 because the district court concluded that the claims were not directed to an abstract idea at Step 1. Free Stream argued that the claims of the ’356 patent “specify the components or methods that permit the television and mobile device to operate in [an] unconventional manner, including the use of fingerprinting, a content identification server, a relevancy-matching server, and bypassing the mobile device security sandbox.”

The argument on Step 2 was also directed around bypassing sandbox security. The Federal Circuit explained that the security sandbox may limit access to the network, but the claimed invention simply seeks to undo that by “working around the existing constraints of the conventional functioning of television and mobile devices.” It was concluded that “such a ‘work around’ or ‘bypassing’ of a client device’s sandbox security does nothing more than describe the abstract idea of providing targeted content to a client device.” The Federal Circuit emphasized that “an abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementing the idea.” Finally, the Federal Circuit found that the asserted claims simply utilized generic computing components arranged in a conventional manner but failed to embody an “inventive solution to a problem.”

Takeaway

- An abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementing the idea.

- The “work-around” does not add more features that give rise to a Step 2 “inventive concept.”

Lying in a Deposition – Never a Good Policy

| June 2, 2021

Cap Export, LLC v. Zinus, Inc.

Decided on May 5, 2021

Summary

Rule 60(b)(3) relieves a patent challenger of a final judgment entered in favor of a patentee where the patent challenger with due diligence could not discover a later-revealed fraud committed by the patentee during the underlying litigation in which the deposed patentee’s witness lied to conceal his knowledge of on-sale prior art determined to be highly material to the validity of the patent.

Details

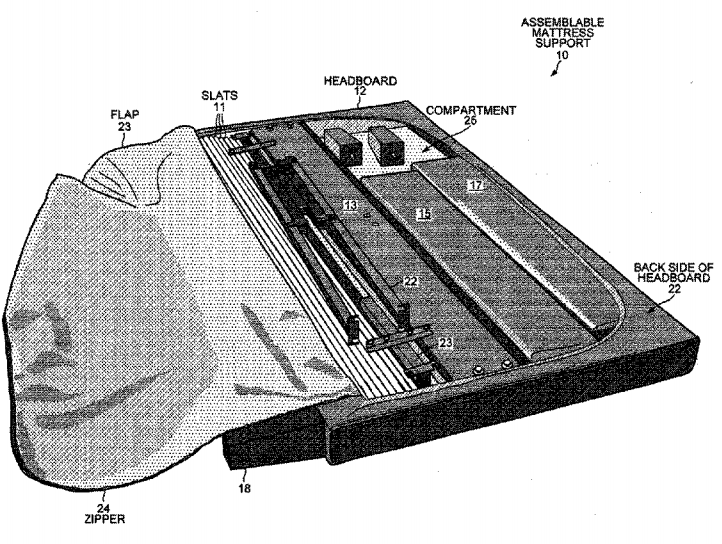

Zinus owns U.S. Patent No. 8,931,123 (“the ’123 patent”) entitled “Assemblable mattress support whose components fit inside the headboard.” The invention allows for packing various components of a bed into its headboard compartment for easy shipping in a compact state. The concept may be seen in one of the ‘123 patent figures:

The application that resulted in the ‘123 patent was filed in September 2013.

In 2016, Cap Export, LLC (“Cap Export”) sought declaratory judgment of invalidity and noninfringement of the ‘123 patent in the Central District of California. The lawsuit eventually resulted in the district court upholding the validity of the ‘123 patent claims as not anticipated or obvious over all prior art references considered. The final judgment stipulated and entered in favor of Zinus included payment of $1.1 million in damages to Zinus, and a permanent injunction against Cap Export[1]. Particularly relevant to the present case is the fact that in the course of the lawsuit, Cap Export deposed Colin Lawrie, Zinus’s president and expert witness, as to his knowledge of various prior art items.

In 2019, Zinus sued another company for infringement of the ‘123 patent. This second lawsuit prompted Cap Export to learn that Zinus’s group company had bought hundreds of beds manufactured by a foreign company which apparently had a bed-in-a-headboard feature, before the filing date of the ‘123 patent. Colin Lawrie, the aforementioned Zinus’s president, appears to be involved in this transaction as the purchase invoice was signed by Lawrie himself.

Cap Export then timely filed a Rule 60(b)(3) motion for relief from the final judgment, alleging that Lawrie during the previous deposition lied to Cap Export’s counsel. Some questions and answers highlighted in the case include:

Q. Prior to September 2013 had you ever seen a bed that was shipped disassembled in one box?

A. No.

Q. Not even—I’m not talking about everything stored in the headboard, I’m just saying one box.

A. No, I don’t think I have.

In the Rule 60(b)(3) proceeding, Lawrie admitted that his deposition testimony was “literally incorrect” while denying intentional falsity because he had misunderstood the question to refer to a bed contained “in one box with all of the components in the headboard,” rather than a bed contained “in one box” (where most laypersons should know of the latter, if not the former).

The district court was not convinced, pointing to the fact that Cap Export’s counsel had rephrased the question to distinguish the two concepts. Also, emails were discovered showing repeated sales of the beds at issue to Zinus’s family companies, the record which Zinus admitted had been in its possession throughout the underlying litigation.

The district court set aside the final judgement under Rule 60(b)(3), finding that the purchased beds were “functionally identical in design” to the ’123 patent claims, and that Lawrie’s repeated denials of his knowledge of such beds amounted to affirmative misrepresentations. Zinus appealed.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed.

FRCP Rule 60(b)(3)

Rule 60(b)(3) relieves a losing party of a final judgment where an opposing party commits “fraud … , misrepresentation, or misconduct.” The Ninth Circuit applies an additional requirement that the fraud not be discoverable through “due diligence”[2]. A movant must prove by clear and convincing evidence that the opposing party has obtained the verdict in its favor through fraudulent conduct which “prevented the losing party from fully and fairly presenting the defense.” Since the issue is procedural, the Federal Circuit follows regional circuit law and reviews the district court decision for abuse of discretion.

Due Diligence in Discovering Fraud

Zinus’s main contention was that the due diligence requirement is not satisfied, arguing that the key evidence would have been discovered had Cap Export’s counsel taken more rigorous discovery measures[3] specific to patent litigation.

The Federal Circuit disagreed, finding that due diligence in discovering fraud is not about the lawyers’ lacking a requisite standard of care, but rather, the question is “whether a reasonable company in Cap Export’s position should have had reason to suspect the fraud … and, if so, took reasonable steps to investigate the fraud.”

Here, Cap Export met the requirement because there was no reason to suspect the fraud in the first place. Lawrie’s repeated denials in the deposition testimony, combined with the impossibility to reach the concealed evidence despite numerous search efforts by Cap Export and the general unavailability of such evidence, forestalled an initial suspicion of fraud which would otherwise call for further inquiry into the possible misconduct.

Opponent’s Fraud Preventing Fair and Full Defense

The Federal Circuit also found that the district court had not abuse its discretion in judging other parts of Rule 60(b)(3) jurisprudence.

As to the existence of fraud, the Federal Circuit approved the district court’s finding of affirmative misrepresentations. There is no clear error where the district court rejected Lawrie’s explanation that the false testimony arose from misunderstanding and was unintentional, which lacks credibility given the fact that the deposition occurred within a few years from the sales at issue.

As to the frustration of fairness and fullness, the Federal Circuit noted that Rule 60(b)(3) standard does not require showing that the result would have been different but for the fraudulently withheld information, but showing the evidence’s “likely worth” is sufficient to establish the harm. As such, the concealed prior art does not have to “qualify as invalidating prior art,” but being “highly material” suffices.

The Federal Circuit endorsed the district court’s judgment that the concealed evidence “would have been material” and its unavailability to Cap Export prevented it from fully and fairly presenting its case. The determination rests on the underlying factual findings that the on-sale prior art is “functionally identical in design” to the ‘123 patent claims, and that without the misrepresentations, the evidence would have been considered by the court in its obvious and anticipation analysis.

The Opinion’s closing remarks appear to suggest an implication of the procedural rules such as Rule 60(b)(3) in allowing the patent system to achieve its core purpose of serving the public interest. Legitimacy of patents is preserved by warding off fraudulent conduct in proceedings before the court, the establishment which works only where parties give entire information for a full and fair determination of their controversy.

Takeaway

- A favorable verdict procured through fraud will be vacated under Rule 60(b)(3).

- Due diligence requirement under Rule 60(b)(3) is unique to the Ninth Circuit. In cases involving the patentee’s knowledge about prior art, reasonableness in the patent challenger’s discovery and investigation tactics, even if they didn’t expose a lie, likely satisfies this additional requirement.

- To establish the evidentiary value of the concealed prior art in a Rule 60(b)(3) motion, a showing that the information is “highly material” to presenting the movant’s case, if not “invalidating” the patent, would be sufficient.

- In the present case, the second lawsuit filed by the patentee (i.e., the lying party) led to the discovery of its own fraud. What could the patent challenger have done to safeguard against the patentee’s lies in the first lawsuit? Perhaps taking patent-specific standard discovery measures such as those noted at footnote 3 might help. Watch out for a patentee’s past transactions involving products manufactured by a third party, which might be “highly material” on-sale prior art simply because of its functional or design similarity to the patent claims.

- After a final judgment is entered, a losing party may benefit from monitoring the opponent’s litigation activity involving the patent at issue, which might lead to discovery of previously unknown information, allowing for a potential Rule 60(b)(3) relief.

[1] And a third-party defendant added during the litigation. The parties on Cap Export’s side are referred to collectively as Cap Export.

[2] The Federal Circuit notes that the diligence requirement is at odds with the plain text of Rule 60(b)(3) and does not appear to be adopted in other regional courts of appeals. Compare Rule 60(b)(2), which states that “newly discovered evidence that, with reasonable diligence, could not have been discovered in time to move for a new trial.”

[3] Such as “[to] specifically seek prior art [in a written discovery request]; … [to] depose the inventor of the ’123 patent; and [to take] a deposition of Lawrie … [specifically] under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 30(b)(6).”