Nexus for Secondary Considerations requires Coextensiveness between a product and the claimed invention

| June 26, 2020

Fox Factory, Inc. v. SRAM, LLC

May 18, 2020

Lourie, Mayer and Wallach. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary:

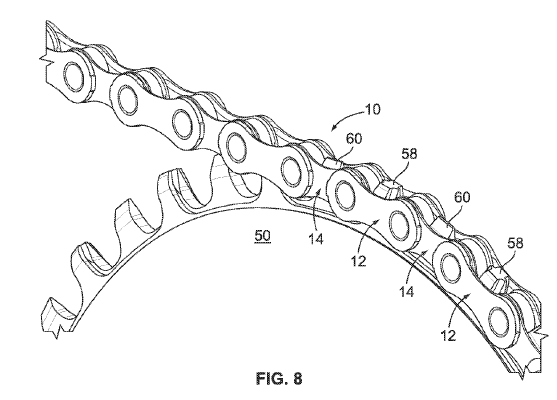

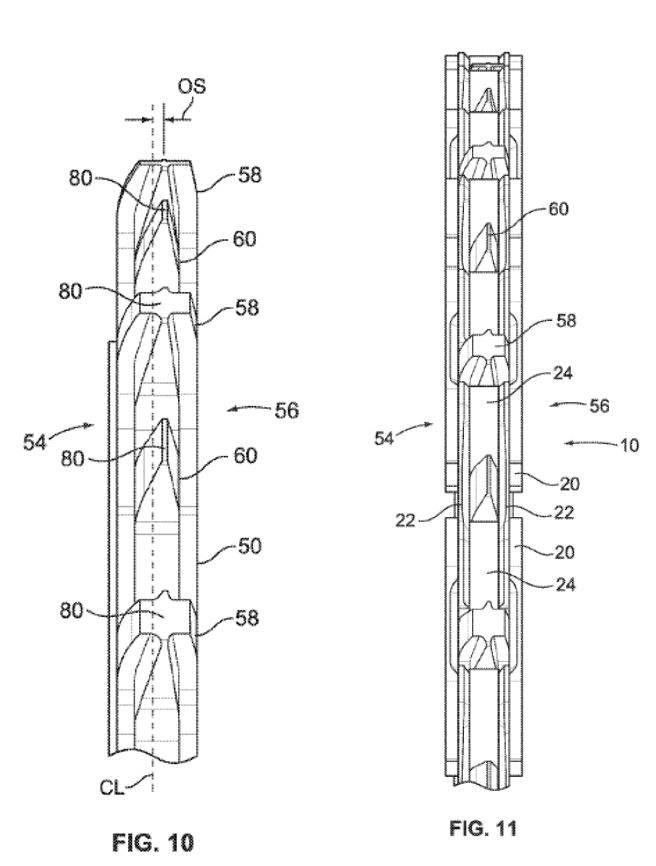

SRAM sued Fox Factory for infringing U.S. Patent 9,291,250 (the ‘250 patent) and the parent patent U.S. Patent 9,182,027 (the ‘027 patent) to bicycle chainrings having teeth that alternate between widened teeth that better fit a gap between outer plates of a chain and narrower teeth to fit a gap between inner plates of a chain. Fox Factory filed IPRs against each patent. SRAM provided evidence of secondary considerations and argued that a greater than 80% gap-filling feature of the X-Sync chainring was crucial to its success for solving chain retention problem. The PTAB held that both patents are not unpatentable as obvious relying in part on secondary consideration evidence provided by SRAM. On appeal, the CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision with regard to the ‘027 patent because the SRAM X-Sync chainring is not coextensive with the claims of the ‘027 patent that do not recite the greater than 80% gap-filling feature. However, the CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s decision for the ‘250 patent because the claims include the greater than 80% gap-filling feature.

Details:

The ’250 patent and the ‘027 patent are to bicycle chainrings. Some figures of the patents are provided below.

This chainring is designed to be a solitary chainring that does not need to switch between different size chainrings. Since it is a solitary chainring, the chainring can be designed to provide a tighter fit with the chain. A conventional chain has links that are alternatingly narrow and wide, but the conventional chainring has teeth that are all the same size. SRAM designed a chairing to have alternating teeth having widened teeth to fit the wide gaps and narrow teeth to fit the narrower gaps. SRAM’s product the X-Sync chainring that implements this design has been praised for its chain retention.

Claim 1 of the ‘250 patent is provided:

1. A bicycle chainring of a bicycle crankset for engagement with a drive chain, comprising:

a plurality of teeth extending from a periphery of the chainring wherein roots of the plurality of teeth are disposed adjacent the periphery of the chainring;

the plurality of teeth including a first group of teeth and a second group of teeth, each of the first group of teeth wider than each of the second group of teeth; and

at least some of the second group of teeth arranged alternatingly and adjacently between the first group of teeth,

wherein the drive chain is a roller drive chain including alternating outer and inner chain links defining outer and inner link spaces, respectively;

wherein each of the first group of teeth is sized and shaped to fit within one of the outer link spaces and each of the second group of teeth is sized and shaped to fit within one of the inner link spaces; and

wherein a maximum axial width about halfway between a root circle and a top land of the first group of teeth fills at least 80 percent of an axial distance defined by the outer link spaces.

In the IPR for the ‘250 patent, Fox Factory cited JP S56-42489 to Shimano and U.S. Patent 3,375,022 to Hattan. Shimano teaches a bicycle chainring with widened teeth to fit into the outer chain links of a conventional chain. Hattan describes that a chainring’s teeth should fill between 74.6% and 96% of the inner chain link space. Fox Factory argued that the claims would have been obvious because one of ordinary skill in the art would have seen the utility in designing a chainring with widened teeth to improve chain retention as taught by Shimano, and one of ordinary skill in the art would have looked to Hattan’s teaching with regard to the percentage of the link space that should be filled.

The PTAB held the claims to be non-obvious because of the axial fill limitation “at the midpoint of the teeth.” The PTAB found that Hattan taught the fill percentage at the bottom of the tooth instead of at the midpoint. The PTAB also found that SRAM’s evidence of secondary considerations rebutted Fox Factory’s arguments of obviousness.

On appeal, Fox Factory argued that the only difference between the prior art and the claimed invention is that the fill limitation is measured halfway up the tooth. Regarding secondary considerations, Fox Factory argued that a nexus between the claimed invention and the evidence of success of the X-Sync chainring was not demonstrated because the success is due to other various unclaimed aspects of the X-Sync chainring.

The CAFC stated that Fox Factory is correct that “a mere change in proportion … involves no more than mechanical skill, rather than the level of invention required by 35 U.S.C. § 103.” However, the CAFC stated that the PTAB “found that SRAM’s optimization of the X-Sync chainring’s teeth, as claimed in the ‘250 patent, displayed significant invention.” The CAFC pointed out that SRAM provided evidence that the success of the X-Sync chainring surprised skilled artisans, evidence of industry skepticism and subsequent praise, and evidence of a long-felt need to solve chain retention problems. The X-Sync chainring also won an award for “Innovation of the Year.” Based on the evidence, the CAFC stated that the PTAB did not err in concluding that the evidence of secondary considerations defeated the contention of routine optimization.

Fox Factory argued that the CAFC’s previous decision on the ‘027 patent requires vacatur in this case. In the appeal of the IPR for the ‘027 patent the CAFC stated that the PTAB misapplied the legal requirement of showing a nexus between evidence of secondary considerations and the obviousness of the claims of the patent. The CAFC stated that the patent owner must show that “the product from which the secondary considerations arose is coextensive with the claimed invention.” In the IPR for the ‘250 patent, SRAM argued that the greater than 80% gap-filling feature of the X-Sync chainring was crucial to its success. But the claims of the ‘027 patent do not include this greater than 80% gap filling feature. Thus, in the ‘027 appeal, the CAFC stated that no reasonable factfinder could decide that the X-Sync chainring was coextensive with a claim that did not include the greater than 80% gap filling feature, and vacated the decision of the PTAB.

In this case, the CAFC pointed out that the claims of the ‘250 patent include the greater than 80% gap filling feature, and thus, the X-Sync chainring is coextensive with the claims. The CAFC also stated that the unclaimed features relied on by Fox Factory as contributing to the success are to some extent incorporated into the 80% gap-filling feature. Thus, the CAFC found that substantial evidence supports the PTAB’s findings on secondary considerations and nexus, and the CAFC stated that they agree with the PTAB’s conclusion that the claims of the ‘250 patent would not have been obvious.

Comments

When arguing secondary considerations, make sure that there is nexus between the evidence and the claims. Specifically, you need to make sure that the product from which the secondary considerations arose is “coextensive” with the claimed invention. A product that falls within the scope of the claim is not necessarily coextensive with the claim.

This case is also a reminder to include claims having varying scope. In this case, SRAM’s claims survived because of the 80% gap-filling feature which was not included in the claims of the parent patent.

Federal Circuit Reverses the District Court’s Award of Attorneys’ Fees Due to the District Court’s Failure to Provide a Clear Explanation of the Supporting Reasons

| June 17, 2020

MUNCHKIN, Inc. v. LUV ‘N Care, Ltd.

June 9, 2020

Dyk, Taranto, and Chen (Opinion by Chen)

Summary

Munchkin, Inc. (Munchkin) sued Luv ‘N Care, Ltd. (LNC) in the District Court for the Central District of California based patent infringement, trademark infringement and trade dress infringement of its’ spill proof containers. Before the District Court, Munchkin voluntarily dismissed all of its’ legal claims against LNC. After dismissal of these claims, LNC filed a motion for attorneys’ fees, which was awarded to LNC by the District Court. On appeal, the Federal Circuit reversed the award of attorneys’ fees, explaining that the District Court abused its’ discretion in awarding attorneys’ fees because LNC’s motion for attorneys’ fees and the District Court’s decision awarding such fees did not provide a clear explanation of the reasons supporting an award for the attorneys’ fees, noting that it is particularly important to provide a clear explanation of the reasons supporting an award for the attorneys’ fees whenthe claims are notfully litigated before the District Court.

Background

- Subject Matter at Issue

The present case relates to spill-proof containers, and involves patent infringement, trademark infringement and trade dress infringement claims related to such spill-proof containers.

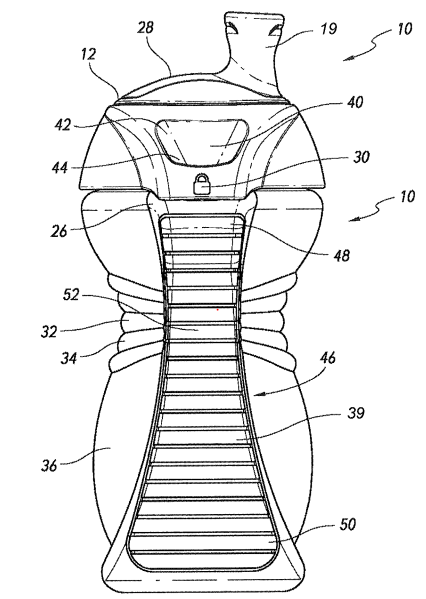

Fig. 3 of U.S. Patent No. 8,739,993

- Procedural Background

This case is an appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California.

Munchkin, Inc. (Munchkin) filed a lawsuit in the District Court against Luv n’ Care, Ltd. (LNC) for trademark infringement and unfair competition claims related to spill-proof drinking containers. A year later, the District Court granted Munchkin leave to amend the complaint to include new trademark infringement claims and trade dress infringement claims and new patent infringement claims based on U.S. Patent No. 8,739,993 (the ’993 patent).

During litigation, Munchkin voluntarily dismissed all of its non-patent claims with prejudice. Then, in an inter partes review (IPR) before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, Munchkin’s patent was held unpatentable. Thereafter, Munchkin voluntarily dismissed its’ patent claims.

Thereafter, LNC filed a motion for attorneys’ fees under 35 U.S.C. § 285 and 15 U.S.C. § 1117(a), and the District Court granted attorneys’ fees to LNC finding the case to be “exceptional” based on LNC’s arguments.

Before the Federal Circuit, Munchkin appeals, arguing that the District Court’s determination that this was an “exceptional” case lacks a proper foundation because LNC’s motion insufficiently presented the required facts and analysis needed to establish that Munchkin’s patent, trademark, and trade dress infringement claims were so substantively meritless to render the case exceptional.

The Federal Circuit’s Decision

The Legal Bases for Attorneys’ Fees

Under 35 U.S.C. § 285 of the Patent Act, “[t]he court in exceptional cases may award reasonable attorney fees to the prevailing party.” Similarly, under 15 U.S.C. § 1117(a) of the Lanham Act pertaining to trademark and trade dress infringement, “[t]he court in exceptional cases may award reasonable attorney fees to the prevailing party.”

In Octane Fitness, 572 U.S. 545 (S. Ct. 2014), the U.S. Supreme Courtheld that an exceptional case is “one that stands out from others with respect to the substantive strength of a party’s litigating position (considering both the governing law and the facts of the case) or the unreasonable manner in which the case was litigated.” This analysis considers the case based on the totality of the circumstances, requiring a movant to show the case is exceptional by a preponderance of the evidence.

The Federal Circuit’s Review

The Federal Circuit reviews the District Court’s determination that a case is exceptional for abuse of discretion. As explained by the Federal Circuit, “[a] District Court abuses its discretion when it makes a clear error of judgment in weighing relevant factors or in basing its decision on an error of law or on clearly erroneous factual findings.”

According to the Federal Circuit, “[w]hile we generally give great deference to a District Court’s exceptional-case determination, a District Court nonetheless must “provide a concise but clear explanation of its reasons for the fee award.”

The Federal Circuit remarked that: “This case represents ‘an unusual basis for fees,’ in that the District Court’s exceptional-case determination rests on an examination of issues—trademark infringement, trade dress validity, and patent validity—that were not fully litigated before the court.” The Federal Circuit further explained that: “when the bases of an attorneys’ fee motion rest on issues that had not been meaningfully considered by the District Court, as is the case here, ‘a fuller explanation of the court’s assessment of a litigant’s position may well be needed when a District Court focuses on a freshly considered issue than one that has already been fully litigated.’” The Federal Circuit also noted that the patent, trademark, and trade dress claims were all new issues presented in the context of the motion for attorneys’ fees, but that LNC failed to make a detailed, fact-based analysis of Munchkin’s litigating positions to establish that the claims were all wholly lacking in merit.

- The Patent Claims

With respect to LNC’s patent claim, the Federal Circuit held that “neither LNC’s fee motion nor the District Court’s opinion comes close to supporting the conclusion that Munchkin acted unreasonably.” The Federal Circuit also points out that the District Court had also adopted Munchkin’s claim interpretation, which “erected a serious hurdle to LNC’s invalidity challenge.” The Federal Circuit added that the fact that the District Court had adopted Munchkin’s claim interpretation made “the need for a full and detailed explanation in this case for why Munchkin’s litigating position was exceptionally weak all the more imperative.”

The Federal Circuit also criticized the District Court’s conclusion that Munchkin unreasonably maintained its’ patent infringement lawsuit once the Patent Board instituted the IPR on the bases that “(1) published statistics at the time indicated that the Patent Board cancels some of a patent’s instituted claims 85% of the time and cancels all of the instituted claims 68% of the time, (2) the Patent Board’s final decision found all of the ’993 patent’s claims unpatentable, and (3) this court summarily affirmed that decision.” The Federal Circuit explained that the IPR statistics combined with the meritorious outcome are not enough, noting that “they tell us nothing about the substantive strength of Munchkin’s litigating position (considering both the governing law and the facts of the case).”

The Federal Circuit also criticized the District Court’s superficial reference to prior art to a Playtex Twist ‘N Click cup product as purportedly evidencing weakness of the validity of the patent because such prior art was not discussed in detail and was not even formally part of the court record. The Federal Circuit explained that LNC’s motion needed to go much further into the facts to meet its’ burden of proof.

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit held that the District Court’s finding in relation to the patent claim was an abuse of discretion. (NOTE: Here, the District Court had actually granted attorneys’ fees for both proceedings before the court and before the U.S.P.T.O. Although the Federal Circuit dismissed the award of attorneys’ fees, the Federal Circuit expressed that it would not address whether 35 U.S.C. 285 permits recovery of attorneys’ fees related to proceedings before the U.S.P.T.O.)

- The Trademark Claims

With respect to LNC’s trademark claim, the Federal Circuit held that an ultimate problem with the District Court’s finding that the trademark claims were “exceptional” under § 1117(a) is that it conflicts with the court’s earlier order granting Munchkin’s motion to amend the complaint to add the new trademark claim. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit indicated that “Munchkin cannot be faulted for litigating a claim it was granted permission to pursue,” especially “[a]bsent misrepresentation to the court.”

Furthermore, the Federal Circuit also noted that as with the patent claims, the District Court was required to make specific findings about the trademark infringement merits themselves, pertaining to a formal likelihood of confusion analysis. Moreover, the Federal Circuit also emphasized that “Munchkin’s dismissal of its claims with prejudice also does not establish, by itself, a finding that the merits were so substantively weak as to render the claims exceptional,” noting that “[t]here are numerous reasons, including Munchkin’s asserted desire to streamline the litigation, to drop a claim, not just substantive weakness.”

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit held that the District Court’s finding in relation to the trademark claim was also an abuse of discretion.

- The Trade Dress Claims

With respect to LNC’s trade dress claim, as with the patent and trademark claims, the Federal Circuit explained that “none of these barebones allegations justify a finding that Munchkin’s position that it owned a protectable, valid trade dress right was unreasonable.” Moreover, the Federal Circuit also noted that, like the trademark claim, the District Court had allowed Munchkin to amend the complaint to add the new trade dress claim.

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit reversed the District Court’s granting of attorneys’ fees.

Takeaways

- When seeking attorneys’ fees in patent, trademark and/or trade dress matters, it is important to make sure that motions for attorneys’ fees provide a clear explanation of the reasons supporting an award for the attorneys’ fees – i.e., the reasons must demonstrate the unreasonableness of opposing party’s conduct under the governing law and the facts of the case.

Tags: 15 U.S.C. § 1117(a) > 35 U.S.C. § 285 > Attorneys’ Fees > Exceptional Cases

A Pencil Copying A Pencil Copying A Pencil: Patented Design Intentionally Resembling A No. 2 Pencil Not Infringed by Copycat

| June 3, 2020

Lanard Toys Limited v. Dolgencorp LLC

May 14, 2020

Before Lourie, Mayer, and Wallach (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

Where a design patent claims an ornamental design that intentionally resembles a common object having a well-known appearance and well-known functional features, such as a No. 2 pencil, the smaller differences in the design take on greater significance in determining not only the scope, but also infringement, of the design patent. The theory of infringement of a design patent cannot be based solely on design elements that are already known in the prior art or that are functional.

Details

Lanard Toys Limited (“Lanard”) is perhaps better known for its long-lasting, massively produced lines of The Corps! action figures, which were marketed as the more affordable alternatives to the G.I. Joe action figures.

But (unfortunately) these action figures are not the toy at issue in Lanard’s dispute with Ja-Ru, Inc. (“Ja-Ru”), a fellow toymaker; Dolgencorp LLC, a distributor; and Toy “R” Us-Delaware, Inc., a toy retailer.

Rather, the toy at issue is a chalk holder in the shape of an oversized, No. 2 pencil that can hold pieces of colored chalk for children to draw on sidewalks.

From 2011 to 2014, Dolgencorp distributed, and Toys “R” Us sold, Lanard’s “chalk pencils”. Then, in 2013, Ja-Ru began marketing its own chalk holder. Ja-Ru admitted during litigation that they had used Lanard’s chalk pencil as a reference for designing and developing their product. Beginning with the 2014 toy season, Dolgencorp and Toys “R” Us stopped ordering Lanard’s chalk pencils, and began offering Ja-Ru’s product instead.

Lanard owns U.S. Design Patent No. D671,167 (“D167 patent”), titled “chalk holder” and claims the “ornamental design for a chalk holder”.

Reproduced below (from left to right) are representative Figure 1 from the D167 patent, Lanard’s chalk pencil, and Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil:

Lanard sued Ja-Ru, Dolgencorp, and Toys “R” Us for design patent infringement.[1] When the parties cross-moved for summary judgment on the question of infringement, the district court sided with Ja-Ru, granting summary judgment that Ja-Ru’s product did not infringe Lanard’s D167 patent. Lanard appealed.

On appeal, Lanard challenges the district court’s claim construction, asserting that the district court erroneously eliminated design elements from the scope of the D167 patent. Second, Lanard challenged the district court’s infringement analysis as failing to comport with the “ordinary observer” test.

The Federal Circuit rejected both of Lanard’s challenges, and adopted the district court’s determinations basically without modification on every one of Lanard’s contentions

Claim construction

Design patents “typically are claimed as shown in drawings”.[2] Functional characteristics in a design may limit the scope of protection, as “the scope of the claim must be construed in order to identify the non-functional aspects of the design as shown in the patent.”[3]

Further, the construction of a design patent involves identifying “various features of the claimed design as they relate to the accused design and the prior art.”[4] Prior art may be especially important in revealing the functionally necessary design elements, where “[e]very piece of prior art identified by the parties that incorporates similar elements configures them in the exact same way.”[5] Those elements represent the “broader general design concepts” that are excluded from design patent protection.

Here, Lanard argues that the district court improperly eliminated elements of the claimed designed based on functionality or lack of novelty.

The Federal Circuit, to the contrary, finds no fault with the district court’s claim construction, going so far as to note approvingly that the district court “followed our claim construction directives to a tee.”

The Federal Circuit appreciates that the district court meticulously factored out the functional “general design concepts” in Lanard’s claimed design:

- the conical tapered piece for holding the chalk in place during use;

- the wide and elongated body for storing the chalk and for the user to grasp;

- the ferrule attaching the eraser to the body of the chalk holder; and

- the eraser.

The Federal Circuit agrees with the district court that the elements listed above are common to No. 2 pencils, and are indeed utilitarian concepts that are found in every piece of writing utensil-related prior art cited during prosecution.

The Federal Circuit also agrees with the district court’s identification of the protectable ornamental elements in the D167 patent:

- the size and angle of taper of the conical piece;

- the hexagonal shape of the body

- the specific grooves on the ferrule;

- the columnar shape of the eraser; and

- the precise proportions of the various design elements relative to each other.

Before the district court, Lanard argued that the prior art does not combine the elements of a pencil with a chalk holder. The district court found Lanard’s argument to be unavailing, and the Federal Circuit agrees wholeheartedly.

Lanard’s argument is analogous to arguing that the intended use of an invention in a utility patent distinguishes the invention over the prior art. Such an argument can be difficult to make for a utility patent, and even more so in the context of a design patent. And the district court concluded as much.

Lanard’s patented design, as shown in the drawings, deliberately mimics a No. 2 pencil. The drawings do not differentiate between a toy and an actual pencil. Further, Lanard’s argument contains an implicit admission that elements of the D167 patent were taken from well-known designs for pencils. If, as Lanard asserted, the intended function was the only difference between Lanard’s design and the prior art, then Lanard’s design would not be patentable. The district court based its infringement analysis on the assumption that the D167 patent was valid.

On a side note, I believe this case is distinguishable from the Federal Circuit’s recent decision in Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2019) (case reviewed presented by Sung-Hoon Kim). In Curver,the Federal Circuit limited the scope of the claimed design (i.e., a pattern for a surface ornamentation) to the article of manufacture recited in the claim (i.e., a chair). However, the Federal Circuitalso noted that they were confronted with an atypical situation in Curver, because in most design patents, the drawings themselves depict a particular article of manufacture. Because the drawings in D167 patent identify the article of manufacture, Curver unlikely would have helped Lanard’s claim construction argument.

Infringement

The “ordinary observer” test for design patent infringement requires a comparison of the similarities in overall designs, not similarities of ornamental features in isolation. Under the “ordinary observer” test, courts may discount functional elements, but the analysis must focus on “how [the ornamental features] impact the overall design.”[6]

As in claim construction, the infringement analysis cannot ignore the prior art:

[T]he ordinary observer is deemed to view the differences between the patented design and the accused product in the context of the prior art. When the differences between the claimed and accused design are viewed in light of the prior art, the attention of the hypothetical ordinary observer will be drawn to those aspects of the claimed design that different from the prior art. And when the claimed design is close to the prior art designs, small differences between the accused design and the claimed design are likely to be important to the eye of the hypothetical ordinary observer.[7]

In this case, the district court determined that as compared to Lanard’s claimed design, Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil had:

- a more rotund and more stunted body;

- a shorter, more gradually sloping, and ridged conical piece; and

- a ferrule with a different pattern.

The district court concluded that, based on those distinctions, an ordinary observer would not consider Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil to have the same design as claimed in the D167 patent.

On appeal, Lanard argues that the district court’s infringement analysis compared the designs on an element-by-element basis, rather than comparing their overall appearances. Lanard also argues that the district court focused on features that distinguished the claimed design over the prior art, so that the district court was in effect reverting to the now-defunct “point of novelty” test. The “point of novelty” test would have asked whether Ja-Ru had stolen the novel aspects of Lanard’s patented design that distinguished it from the prior art.

The Federal Circuit rejects both of Lanard’s arguments.

As the district court noted, and which the Federal Circuit agrees, the problem for Lanard is that the asserted design similarities between the claimed design and Ja-Ru’s product stem from aspects of the design that are either functional or well-established in the prior art.

Lanard wants the district court and the Federal Circuit to find infringement on the basis that Ja-Ru’s product and the claimed design share the overall appearance of a No. 2 pencil. But this is precisely the argument that Lanard should not make.

Any aspect of Lanard’s claimed design that relates to the function of a No. 2 pencil or the conventional, well-known appearance of a No. 2 pencil are not patentable, and as such, are excluded from the scope of the design patent during claim construction and cannot be the basis for establishing infringement.

Lanard’s argument is made weaker by the ubiquity of No. 2 pencils. The Federal Circuit agrees with the district court’s finding that, because of the crowdedness of the field of pencils or writing utensils in general, the ornamental features in Lanard’s claimed design which are not dictated by function and which are not in the prior art take on greater significance. Far from being inconsequential and minor, those ornamental distinctions would dominate an ordinary observer’s attention when evaluating the overall appearances of Ja-Ru’s product and Lanard’s claimed design. The Federal Circuit agrees with the district court that those ornamental distinctions are sufficient to preclude a finding of infringement.

What troubles the district court and the Federal Circuit especially is what they perceive to be an attempt by Lanard to monopolize the basic design concepts underlying a pencil. They believe that Lanard’s arguments, if accepted, would “exclude any chalk holder in the shape of a pencil and thus extend the scope of the D167 patent far beyond the statutorily protected ‘new, original and ornamental design’.”

Takeaway

- In a crowded art, the devil and God are in the detail. The nuances in a design can take on greater significance where the article of manufacture embodying the design (or the article of manufacture that the design is intended to resemble) has a well-known appearance.

- While the scope of a design patent is limited to the drawings, courts during litigation have often relied on “verbal descriptions” of the claimed design to construe the claim. Be strategic about those verbal descriptions. For example, a quick review of the prior art cited during prosecution suggests that Lanard’s claimed design and the design of Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil may be closer to each other than to the cited prior art—in that case, Lanard might have offered a verbal description of the D167 patent drawings that downplayed the differences between those drawings and Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil, and still distinguished over the prior art.

- Drawings in a design patent application should reflect the intended function of the claimed design. A potential weakness in Lanard’s design patent may be that the drawings look too much like the article of manufacture (i.e., No. 2 pencil) that the claimed design is intended to resemble. If Lanard’s intention was to claim an oversized, toyish rendition of the No. 2 pencil, perhaps the patent drawings could have better emphasized the exaggerated proportions of the various chalk holder parts relative to each other.

[1] Lanard also alleged copyright and trade dress infringement, but this review will focus only on the design patent issues.

[2] Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665, 679 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

[3] Sport Dimension, Inc. v. Coleman Co., 820 F.3d 1316, 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

[4] Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 680.

[5] Richardson v. Stanley Works, Inc., 610 F.Supp.2d 1046, 1049 (D. Ariz. 2009), aff’d 597 F.3d 1288 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

[6] Richardson, 597 F.3d at 1295.

[7] Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 671.