The disclosure-dedication doctrine applies at limitation level, not at embodiment level

| May 27, 2020

Eagle Pharmaceutical Inc. v. Slayback Pharm LLC

May 8, 2020

O’Malley (Opinion author), Reyna, and Chen

Summary

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s holding that the disclosure-dedication doctrine applies here to bar application of the doctrine of equivalents and, accordingly, the Slayback’s generic products do not infringe the Eagle’s four patents.

Details

Slayback filed new drug application (“NDA”) for a generic version of Eagle’s branded bendamustine product, BELRAPZO®. Bendamustine is used to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia and indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Eagle sued Slayback for infringing four patents in the District Court for the District of Delaware. Eagle’s four asserted patents share essentially the same written description. One of the four patents is U.S. Patent No. 9,572,796 (“the ’796 patent”), which has a representative claim 1 as shown below:

1. A non-aqueous liquid composition comprising: bendamustine, or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof;

a pharmaceutically acceptable fluid comprising a mixture of polyethylene glycol and propylene glycol, wherein the ratio of polyethylene glycol to propylene glycol in the pharmaceutically acceptable fluid is from about 95:5 to about 50:50; and

a stabilizing amount of an antioxidant;

. . . .

In the district court, Slayback conceded that its generic product literally infringes all limitations of claim 1 except for the “pharmaceutically acceptable fluid” limitation. Slayback uses ethanol instead of propylene glycol (PG) in its generic product. Eagle argued that the ethanol in Slayback’s product is insubstantially different from the propylene PG in the claimed composition and, accordingly, Slayback’s product infringes under the doctrine of equivalents.

Slayback moved for a judgment of non-infringement on the pleadings under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(c). Slayback argued that the disclosure-dedication doctrine barred Eagle’s claim of infringement under the doctrine of equivalents because the asserted patents disclose, but do not claim, ethanol as an alternative solvent to PG. Eagle counter-argued that the disclosure-dedication doctrine does not apply here because the asserted patents do not disclose ethanol as an alternative to PG for the claimed embodiment that contains an antioxidant. In fact, the specification only discloses ethanol when discussing unclaimed embodiments that contain chloride salt. Specifically, the asserted patents disclose three distinct “categories” of bendamustine formulations: (i) chloride salt formulations; (ii) antioxidant formulations; and (iii) dimethyl sulfoxide (“DMSO”) formulations. The specification only discloses ethanol as an alternative to PG when discussing the unclaimed chloride salt formulations; and it never discloses ethanol as an alternative to PG when discussing the claimed antioxidant formulations. Eagle also submitted an expert declaration from Dr. Mansoor Amiji in support of its opposition. Nevertheless, the district court held for Slayback because the asserted specification expressly and repeatedly identifies “ethanol” as an alternative “pharmaceutically acceptable fluid” to PG.

The federal circuit affirms the district court’s holding. The disclosure-dedication doctrine does not require the specification to disclose the allegedly dedicated subject matter in an embodiment that exactly matches the claimed embodiment. Instead, the disclosure-dedication doctrine requires only that the specification disclose the unclaimed matter as an alternative to the relevant claim limitation. That is, the disclosure-dedication doctrine requires disclosure of alternatives only at limitation level, not at embodiment level. In this case, the asserted patents disclose ethanol as an alternative to PG in the “pharmaceutically acceptable fluid” claim limitation. The specification repeatedly identifies—without qualification—ethanol as an alternative pharmaceutically acceptable fluid. Aside from the description of certain exemplary embodiments, nothing in the specification suggests that these repeated disclosures of ethanol are limited to certain formulations, or that they cannot extend to the claimed formulation.

Eagle also challenges the district court’s decision from the procedural grounds. Eagle argues that the district court erred by resolving that factual dispute at the pleading’s stage without drawing all reasonable inferences in Eagle’s favor. The federal circuit held that the district court has discretion to consider evidence outside the complaint for purposes of deciding whether to accept that evidence and convert the motion into one for summary judgment. In this case, the district court decided that Eagle was trying to fabricate a factual dispute and Slayback is entitled to judgment in its favor as a matter of law.

Take away

- The disclosure-dedication doctrine applies at limitation level, not at embodiment level.

- A patent drafter should be careful that the scopes of claims are consistent with the disclosure of specification to avoid inadvertent disclosure-dedication.

Tags: disclosure-dedication doctrine > doctrine of equivalent > patent infringement

PETITION DENIED: AI MACHINE CANNOT BE LISTED AS AN INVENTOR

| May 21, 2020

In re Application of Application No. 16/524,350 (“Devices and Methods for Attracting Enhanced Attention”)

April 27, 2020

Robert W. Bahr (Deputy Commissioner for Patent Examination Policy)

Summary:

The PTO denied a petition to vacate a Notice to File Missing Parts of Nonprovisional Application because an AI machine cannot be listed as an inventor based on the relevant patent statutes, case laws from the Federal Circuit, and the relevant sections in the MPEP. The PTO did not find the petitioner’s policy arguments persuasive.

Details:

This application was filed on July 29, 2019. Its Application data sheet (ADS) included a single inventor with the given name “DABUS[1]” and the family name “Invention generated by artificial intelligence.” The ADS identified the Applicant as the Assignee “Stephen L. Thaler.” Also, a substitute statement (in lieu of declaration) executed by Mr. Thaler was submitted, and an assignment document executed by Mr. Thaler on behalf of both DABUS and himself was submitted. Finally, an “Inventorship Statement,” which stated that the invention was conceived by “DABUS” and it should be named as the inventor, was also submitted.

Afterward, the PTO issued a first Notice to File Missing Parts on August 8, 2019, which indicated that the ADS “does not identify each inventor by his or her legal name,” and an surcharge of $80 is due for late submission of the inventor’s oath or declaration.

Mr. Thaler filed a petition on August 29, 2019, requesting supervisory review of the first Notice.

The PTO issued a second Notice to File Missing Parts on December 13, 2019. The PTO dismissed the petition filed on August 29, 2019 in a decision issued on December 17, 2019.

Mr. Thaler filed a second petition on January 20, 2020, requesting reconsideration of the decision issued on December 17, 2019.

Relevant Statutes cited by the PTO

35 U.S.C. §100(f):

The term “inventor” means the individual or, if a joint invention, the individuals collectively who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.

35 U.S.C. §100(g):

The terms “joint inventor” and “coinventor” mean any 1 of the individuals who invented or discovered the subject matter of a joint invention.

35 U.S.C. §101:

Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

35 U.S.C. §115(a):

An application for patent that is filed under section 111 (a) or commences the national stage under section 371 shall include, or be amended to include, the name of the inventor for any invention claimed in the application. Except as otherwise provided in this section, each individual who is the inventor or a joint inventor of a claimed invention in an application for patent shall execute an oath or declaration in connection with the application

35 U.S.C. §115(b):

An oath or declaration under subsection (a) shall contain statements that … such individual believes himself or herself to be the original inventor or an original joint inventor of a claimed invention in the application.

35 U.S.C. §115(h)(1):

Any person making a statement required under this section may withdraw, replace, or otherwise correct the statement at any time.

The PTO’s reasoning

Citing the above statutes, the PTO found that the patent statutes preclude the petitioner’s broad interpretation that an “inventor” could be construed to cover machines. That is, the PTO asserted that such broad interpretation could contradict the plain reading of the patent statutes.

The PTO also cited the case law from the Federal Circuit to dismiss the petitioner’s argument. For example, in Univ. of Utah v. Max-Planck-Gesellschajt zur Forderung der Wissenschajten e. V (734 F.3d 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2013), the CAFC held that a state could not be an inventor. In Beech Aircraft Corp. v. EDO Corp. (990 F.2d 1237 (Fed. Cir. 1993), the CAFC held that “only natural persons can be ‘inventor.’”

Furthermore, the PTO cited the relevant sections in the MPEP to support their position. The PTO indicated that the MPEP defines “conception” as “the complete performance of the mental part of the inventive act” and it is “the formation in the mind of the inventor of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention as it is thereafter to be applied in practice.” The PTO asserted that the use of terms such as “mental” and “mind” indicates that conception must be performed by a natural person.

The PTO rejected the petitioner’s argument that the PTO should take into account the position adopted by the EPO and the UKIPO that DABUS created the invention, but DABUS cannot be named as the inventor. The PTO indicated that the EPO and the UKIPO are interpreting and enforcing their own laws.

The PTO also rejected the petitioner’s argument that inventorship should not be a substantial condition for the grant of patents by arguing that “inventorship has long been a condition for patentability.” The PTO rejected the notion that the granting of a patent for an invention that covers a machine does not mean that the patent statutes allow that machined to be listed as an inventor in another patent application.

Finally, the petitioner provided some policy considerations to support his position: (1) this would incentivize innovation using AI systems, (2) would reduce the improper naming of persons as inventor who do not qualify as inventors, and (3) would inform the public of the actual inventors of an invention. The PTO rejected the petitioner’s policy considerations by arguing that they do not overcome the plain language of the patent statutes.

Takeaway:

- At this point, it appears that it is not possible to list an AI machine as an inventor in the U.S. patent applications. The EPO reached a similar decision in December. It is known that the Japanese Patent Act and the Korean Patent Act do not include an explicit definition of an inventor. Also, the Chinese State Council called for “better IP protections to promote AI.”

- Congress needs to work on this issue because the patent system is in place to incentive innovation in technology, and eventually, increase investment for more jobs.

- A lack of patent protection for inventions developed by AI would decrease investment in the development and use of AI.

- However, there is a concern, among other things, that the PTO may not be able to deal with situations where AI created enormous amount of prior arts to be reviewed by the Examiners.

- Human programmer of AI or the one who defined the task of AI machine could be listed as the named inventor.

[1] DABUS stands for “Device for Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience.” Mr. Thaler asserts that DABUS is a creativity machine programmed as a series of neural networks that have been trained with general information in the field of endeavor to independently create invention. In addition, Mr. Thaler asserts that this machine was “not created to solve any particular problem and not trained on any special data relevant to the instant invention.” Furthermore, Mr. Thaler asserts that this machine recognized “the novelty and salience of the instant invention.”

Tags: 35 U.S.C. §100 > artificial intelligence > conception > DABUS > inventorship > Petition

Patent Term Extension under 35 U.S.C. §156 is Limited to the FDA-Approved Active Ingredient and Salts or Esters thereof—but not Metabolites or Compounds Sharing an Active Moiety

| May 13, 2020

Biogen International GmbH v. Banner Life Sciences

April 21, 2020

Lourie, Moore, and Chen. Opinion by Lourie

Summary

In a case focusing on the meaning of a “product” under 35 U.S.C. §156, the CAFC concluded that the scope of patent term extension is limited to the FDA-approved active ingredient and salts or ester thereof, and does not more broadly include metabolites or other compounds sharing an active moiety with the approved product. Thus, the extension of Biogen’s ‘001 patent does not include some other products within the scope of the claims, such as the metabolite MMF.

Details

Background and District Court holding

Biogen is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 7,619,001, which claims a method of treating multiple sclerosis. Claim 1 is as follows:

A method of treating multiple sclerosis comprising administering, to a patient in need of treatment for multiple sclerosis, an amount of a pharmaceutical preparation effective for treating multiple sclerosis, the pharmaceutical preparation comprising

at least one excipient or at least one carrier or at least one combination thereof; and

dimethyl fumarate, methyl hydrogen fumarate, or a combination thereof.

Biogen also holds the New Drug Application (NDA) for dimethyl fumarate (DMF). This was approved by the FDA in 2013 and is marketed as Tecfidera® “for the treatment of patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis” at a dose of 480 mg.

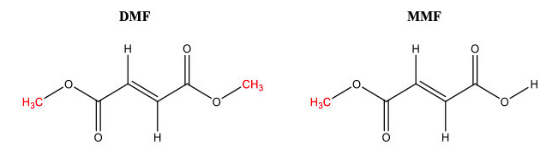

DMF is a double ester which, upon administration to the patient, metabolizes into monomethyl fumarate (MMF) (another name for the claimed “methyl hydrogen fumarate”). Both DMF and MMF are illustrated below.

The ‘001 patent is was originally set to expire on April 1, 2018, but was awarded 818 days of patent term extension to June 20, 2020 under 35 U.S.C. 156 (not to be confused with patent term adjustment under 35 U.S.C. 154). This compensated Biogen for the FDA review period of Tecfidera. The question presented to the CAFC is whether MMF is covered by the 818-day PTE extension along with DMF.

In 2018, Banner filed a “paper NDA” under 21 U.S.C. 355(b)(2) to market a drug having MMF as the active ingredient. Banner could rely on Biogen’s clinical data to show safety and efficacy, and only had to demonstrate bioequivalence. Biogen then sued Banner for infringement.

In reply, Banner argued that the PTE under §156 was limited to uses including the approved product: DMF and its salts or esters, and did not include MMF. The relevant portions of §156 are presented below:

(a) The term of a patent which claims a product, a method of using a product, or a method of manufacturing a product shall be extended in accordance with this section from the original expiration date of the patent, which shall include any patent term adjustment granted under section 154(b),…

(b) Except as provided in subsection (d)(5)(F), the rights derived from any patent the term of which is extended under this section shall during the period during which the term of the patent is extended—….

(2) in the case of a patent which claims a method of using a product, be limited to any use claimed by the patent and approved for the product—

(A) before the expiration of the term of the patent—

(i) under any provision of law under which an applicable regulatory review occurred, and

(ii) under the provision of law under which any regulatory review described in paragraph (1), (4), or (5) of subsection (g) occurred, and

(B) on or after the expiration of the regulatory review period upon which the extension of the patent was based; and….

(f) For purposes of this section:

(1) The term “product” means:

(A) A drug product…..

(2) The term “drug product” means the active ingredient of—

(A) a new drug, antibiotic drug, or human biological product…including any salt or ester of the active ingredient, as a single entity or in combination with another active ingredient.

Meanwhile, Biogen argued that §156(b)(2) does not limit the PTE to uses of the approved product, but rather to all products within the scope of the claim. Additionally, Biogen argued that “product” of §156 should be more broadly interpreted as any compound that shares the “active moiety” with the approved product. The district court sided with Banner.

CAFC

First, the CAFC noted that the purpose of §156 PTE is to compensate a patent owner for regulatory delays, and that this is limited to one patent per approved product. The court also noted that §156 defines the scope of the product as “the active ingredient of…a new drug…including any salt or ester of the active ingredient.”

Biogen cited Pfizer Inc. v. Dr. Reddy’s Labs, Ltd. 359 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2004) to support the position that that “product” under §156 should be interpreted more broadly, especially where “a later applicant’s patentably indistinct drug product…relies on the patentee’s clinical data.” The CAFC did not accept this argument. In Pfizer, the question was whether an extension for amlodipine included amlodipine maleate. However, the CAFC concluded that amlodipine maleate in Pfizer was included under the extension because amlodipine maleate is a salt of the active ingredient (amlodipine), and not because these two compounds share an “active moiety.” On the other hand, in this case, MMF is not a salt or ester of DMF. Rather, MMF is a de-esterified form of DMF. The CAFC’s comments regarding clinical data were provided in Pfizer merely to clarify the purpose of §156(f) and provide context.

The parties also cited to Glaxo Ops. UK Ltd. v. Quigg, 894 F.2d 392 (Fed. Cir. 1990). However, the CAFC concluded that this case was not pertinent to the present issue. Glaxo involved an approved product having cerufoxime as its active ingredient and a second approved product having cerufoxime axetil as its active ingredient, cerufoxime axetil being an ester of cerufoxime. In Glaxo, the question was not whether cerufoxime axetil should be included in an extension for cerufoxime, but rather whether cerufoxime axetil was eligible for its own separate PTE. Since this is not the issue in the present case, the CAFC side-stepped Glaxo.

Additionally, Biogen cited to PhotoCure ASA v. Kappos, 603 F.3d 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2004). In PhotoCure, the CAFC indicated that a new ester could be separately patentable. However, the CAFC indicated that PhotoCure presented a similar situation as Glaxo: a separate extension for a new ester.

Thus, the CAFC held that the definition of “product” according to §156 is the “active ingredient ….including any salt or ester of the active ingredient.” This is not necessarily the same as “active moiety.” As such, “product” only means the active ingredient designated on the FDA approved label, and changes resulting in a salt or ester. However, “product” does not include metabolites of the active ingredient, or de-esterified forms thereof. Here, MMF is a de-esterified metabolite of DMF, rather than a salt of DMF.

Next, Biogen argued that, unlike §156(b)(1), §156(b)(2) does not limit the extension to approved uses of the approved product, but only to approved uses of any approved product. However, the CAFC dismissed this by holding that the approved product in this case is DMF, not MMF, and that it would not make sense for an extension to apply to a different product for which the NDA holder was never subjected to review.

Finally, Biogen argued that the Banner infringes under the doctrine of the equivalents. However, the CAFC dismissed this argument on that basis that a product or process cannot logically infringe an extended claim under equivalents if it is statutorily not included in the §156 extension.

Take Away

Unlike patent term adjustment under §154, which covers the full scope of the patent, patent term extension under §156 is limited in scope to a product having the active ingredient granted regulatory approval by the FDA. The “product” will be narrowly interpreted as the approved active ingredient, as well as salts and esters thereof. As such, patent term extension under §156 is not so broad to cover metabolites and other compounds which share an active moiety with the approved drug.

Interestingly, this case was decided near in time to an important IPR involving the same drug. In February, the PTAB sided with Biogen in a challenge to U.S. Patent No. 8,399,514 by Mylan Pharmaceuticals. The ‘514 patent was very similar to the claims of the ‘001 patent, but recited oral administration and a specific dosage. The PTAB indicated that the dosage was not obvious from the prior art and thus confirmed the validity of the valuable ‘514 patent. The ‘514 patent is the last unexpired patent in the family covering Tecfidera, and is set to expire in 2028.

Additionally, upon the CAFC’s decision, the FDA granted final approval on April 30 to Banner’s MMF-based drug, which will be marketed as Bafiertam ®.

The Federal Circuit declined to be bound by the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance by the Patent Office, but affirmed the Board’s conclusion of the ineligibility, which relied on the Guidance

| May 7, 2020

In re Rudy

April 24, 2020

Prost, Chief Judge, O’Malley and Taranto. Court opinion by Prost.

Summary

The Federal Circuit declined to be bound by the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance by the Patent Office, and instead followed the Supreme Court’s Alice/Mayo framework, and the Federal Circuit’s interpretation and application thereof. However, the Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed the Board’ affirmance of the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application as patent-ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101, which was fully relied on the Office Guidance.

Details

I. background

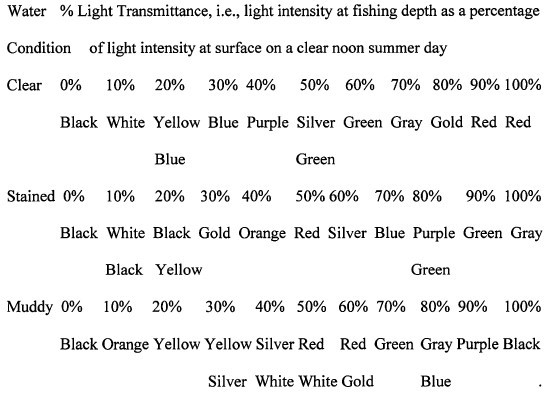

United States Patent Application No. 07/425,360 (“the ’360 application”), filed by Christopher Rudy on October 21, 1989 (before the signing of the 1994 Uruguay Round Agreements Act), is entitled “Eyeless, Knotless, Colorable and/or Translucent/Transparent Fishing Hooks with Associatable Apparatus and Methods.” After a lengthy prosecution of more than twenty years, including numerous amendments and petitions, four Board appeals, and a previous trip to the Federal Circuit where the obviousness of all claims then on appeal was affirmed (In re Rudy, 558 F. App’x. 1011 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (non-precedential)), claim 34, which the Board considered illustrative, reads as follows:

34. A method for fishing comprising steps of

(1) observing clarity of water to be fished to deter- mine whether the water is clear, stained, or muddy,

(2) measuring light transmittance at a depth in the water where a fishing hook is to be placed, and then

(3) selecting a colored or colorless quality of the fishing hook to be used by matching the observed water conditions ((1) and (2)) with a color or colorless quality which has been previously determined to be less attractive under said conditions than has undergone those pointed out by the following correlation for fish-attractive non-fluorescent colors:

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) affirmed the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application in the last Board appeal. The Board conducted its analysis under a dual framework for patent eligibility, purporting to apply both 1) “the two-step framework described in Mayo [Collaborative Ser- vices v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012)] and Alice [Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014)],” and 2) the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance, 84 Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019) (“Office Guidance”), published by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“Patent Office”). Specifically, the Board concluded “[u]nder the first step of the Alice/Mayo framework and Step 2A, Prong 1, of [the] Office Guidelines” that claim 34 is directed to the abstract idea of “select[ing] a colored or colorless quality of a fishing hook based on observed and measured water conditions, which is a concept performed in the human mind.” The Board went on to conclude that “[u]nder the second step in the Alice/Mayo framework, and Step 2B of the 2019 Revised Guidance, we determine that the claim limitations, taken individually or as an ordered combination, do not amount to significantly more than” the abstract idea.

Mr. Rudy timely appealed, challenging both the Board’s reliance on the Office Guidance, and the Board’s ultimate conclusion that the claims are not patent eligible.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed the Board’ affirmance of the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application.

1. Office Guidance vs. Case Law

Mr. Rudy contended that the Board “misapplied or refused to apply . . . case law” in its subject matter eligibility analysis and committed legal error by instead applying the Office Guidance “as if it were prevailing law.”

The Federal Circuit agreed with Mr. Rudy, stating: “[w]e are not[] bound by the Office Guidance, which cannot modify or supplant the Supreme Court’s law regarding patent eligibility, or our interpretation and application thereof.” Interestingly, the Federal cited a non-precedential opinion to support its position: “As we have previously explained:

While we greatly respect the PTO’s expertise on all matters relating to patentability, including patent eligibility, we are not bound by its guidance. And, especially regarding the issue of patent eligibility and the efforts of the courts to determine the distinction between claims directed to [judicial exceptions] and those directed to patent-eligible ap- plications of those [exceptions], we are mindful of the need for consistent application of our case law.

Cleveland Clinic Found. v. True Health Diagnostics LLC, 760 F. App’x. 1013, 1020 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (non-precedential). ”

In conclusion, the Federal Circuit declared: “[t]o the extent the Office Guidance contradicts or does not fully accord with our caselaw, it is our caselaw, and the Supreme Court precedent it is based upon, that must control.”

2. Subject Matter Eligibility of Rudy’s Case

The Federal Circuit concluded that although a portion of the Board’s analysis is framed as a recitation of the Office Guidance, the Board’s reasoning and conclusion for Rudy’s case are nevertheless fully in accord with the relevant caselaw in this particular case.

To determine whether a patent claim is ineligible subject matter, the U.S. Supreme Court has established a two-step Alice/Mayo framework. In Step One, courts must determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as an abstract idea. Alice, 573 U.S. at 208. In Step Two, if the claims are directed to an abstract idea, the courts must “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application.” Id. To transform an abstract idea into a patent-eligible application, the claims must do “more than simply stat[e] the abstract idea while adding the words ‘apply it.’” Id. at 221. At each step, the claims are considered as a whole. See id. at 218 n.3, 225.

a. Step One

With respect to claim 34, the Federal Circuit concluded, as the Board did, that the claim is directed to the abstract idea of selecting a fishing hook based on observed water conditions. Specifically, the Federal Circuit compared claim 34 with Elec. Power Grp., and reasoned that claim 34 requires nothing more than collecting information (water clarity and light transmittance) and analyzing that information (by applying the chart included in the claim), which collectively amount to the abstract idea of selecting a fishing hook based on the observed water conditions. See Elec. Power Grp., LLC v. Alstom S.A., 830 F.3d 1350, 1353–54 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (the Federal Circuit held in the computer context that “collecting information” and “analyzing” that information are within the realm of abstract ideas.).

The Federal Circuit disagreed with Mr. Rudy’s contention that claim 34’s preamble, “a method for fishing,” is a substantive claim limitation such that each claim requires actually attempting to catch a fish by placing the selected fishing hook in the water. The Federal Circuit reasoned that such an “additional limitation,” even if that were true, would not alter the conclusion because the character of claim 34 as a whole remains directed to an abstract idea.

The Federal Circuit also disagreed with Mr. Rudy’s contention that claim 34 is not directed to an abstract idea both because fishing “is a practical technological field . . . recognized by the PTO” and because he contends that observing light transmittance is unlikely to be performed mentally. Regarding the “practical technological field,” the Court reasoned that the undisputed fact that an applicant can obtain subject-matter eligible claims in the field of fishing is irrelevant to the fact that the claims currently before the Court are not eligible. Regarding the unlikeliness of the mental performance, the Court pointed our that the plain language of the claims encompasses such mental determination.

The Federal Circuit further rejected Mr. Rudy’s contention that, relying on the machine-or-transformation test, practicing claim 34 “acts upon or transforms fish” by transforming “freely swimming fish to hooked and landed fish” or by transforming a fishing hook “from one not having a target fish on it to one dressed with a fish when a successful strike ensues.” The Court declined to decide in this case whether the transformation from free fish to hooked fish is the type of transformation discussed in Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 604 (2010) and its predecessor cases. Instead, the Court stated that claim 34 does not actually recite or require the purported transformation that Mr. Rudy relies upon because, as Mr. Rudy’s explained, “landing a fish is never a sure thing. Many an angler has gone fishing and returned empty handed.”

b. Step Two

In the Step Two Analysis, the Court concluded that claim 34 fails to recite an inventive concept at step two of the Alice/Mayo test, and is thus not patent eligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101 because the three elements of the claim (observing water clarity, measuring light transmittance, and selecting the color of the hook to be used), either individually or as an ordered combination, do not amount to “‘significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself.’” The argument in the Step Two Analysis appears somewhat cursory.

c. The Remaining Claims

The Federal Circuit concluded that claim 38, the only other independent claim on appeal, is not patent-eligible as well.

Claim 38 begins with a method that is substantively identical to claim 34, but includes a slightly different chart for selecting the fishing hook color, and further includes only one additional limitation, which recites: “wherein the fishing hook used is disintegrated from but is otherwise connectable to a fishing lure or other tackle and has a shaft portion, a bend portion connected to the shaft portion, and a barb or point at the terminus of the bend, and wherein the fishing hook used is made of a suitable material, which permits transmittance of light therethrough and is colored to colorless in nature.”

The Court stated that the slightly different substance of claim 38’s chart does not render it patent eligible because the substance of claim 34’s hook color chart was not the basis of the eligibility determination. The Court further stated that its step-one analysis of claim 34 is equally applicable to claim 38 because, as described above, this limitation does not change the fact that the character of the claim, as a whole, is directed to an abstract idea.

The Court also affirmed the Board’s conclusions that dependent claims 35, 37, and 40 are not patent eligible, as each recites the physical attributes of the connection between the fishing hook and the fishing lure in ways not meaningfully distinct from claim 38.

The Court further affirm the Board’s conclusions regarding claims 45–49, which differ from the previously discussed claims only in that they mandate a specific color of fishing hook, which neither changes the character of the claims as a whole, nor provides an inventive concept distinct from the abstract idea itself.

Takeaway

· The case demonstrates that courts still stick to the comparative approach in Alice step one, instead of defining or categorizing the “abstract idea.” This approach is notably in contrast with that of the Patent Office, which follows the Office Guidance, dividing Alice step one into two inquiries: (i) evaluate whether the claim recites a judicial exception; and (ii) evaluate whether the judicial exception is integrated into a practical application if the claim recites a judicial exception.

· To be on the safe side for the purpose of drafting a patent specification including claim(s), which is robust to an invalidity defense under 35 U.S.C. § 101, the Supreme Court’s law regarding patent eligibility, and the Federal Circuit’s interpretation and application thereof, not the Office Guidance, shall be relied on.