When there is competing evidence as to whether a prior art reference is a proper primary reference, an invalidity decision cannot be made as a matter of law at summary judgment

| April 29, 2020

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. v. Ultraproof, Inc., et al.

April 17, 2020

Newman, Lourie, Reyna (Opinion by Reyna; Dissent by Lourie)

Summary

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. (“Spigen”) sued Ultraproof, Inc. (“Ultraproof”) for infringement of its multiple patents directed to designs for cellular phone cases. The district court held that as a matter of law, Spigen’s design patents were obvious over prior art references, and granted Ultraproof’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity. However, based on the competing evidence presented by the parties, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) reversed and remanded, holding that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the primary reference was proper.

原告Spigen社は、自身の所有する複数の携帯電話ケースに関する意匠特許を被告Ultraproof社が侵害しているとして、提訴した。地裁は、原告の意匠特許は、先行技術文献により自明であるとして、裁判官は被告のサマリージャッジメントの申し立てを容認した。しかしながら、連邦控訴巡回裁判所(CAFC)は、双方の提示している証拠には「重要な事実についての真の争い(genuine dispute of material fact)」があるとして、地裁の判決を覆し、事件を差し戻した。

Details

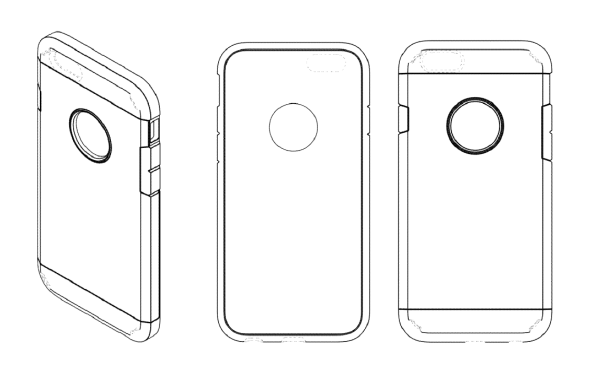

Spigen is the owner of U.S. Design Patent Nos. D771,607 (“the ’607 patent”), D775,620 (“the ’620 patent”), and D776,648 (“the ’648 patent”) (collectively the “Spigen Design Patents”), each of which claims a cellular phone case. Figures 3-5 of the ’607 patent are as shown below:

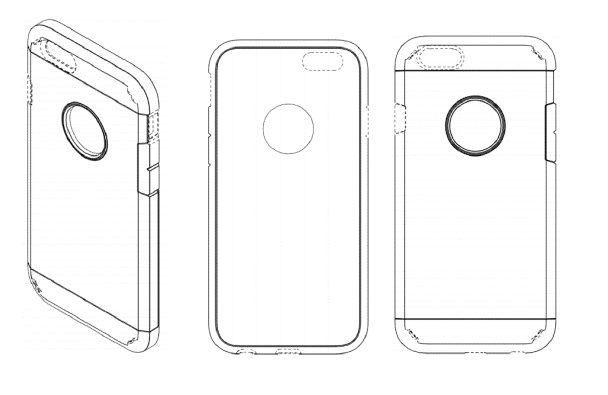

The ’620 patent disclaims certain elements shown in the ’607 patent, and Figures 3-5 of the ’620 patent are shown below:

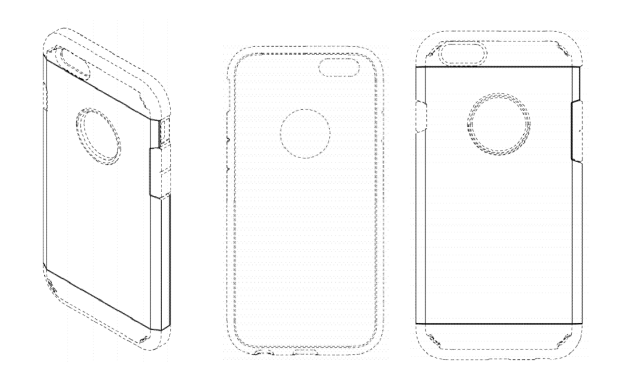

Finally, the ’648 patent disclaims most of the elements present in the ’620 patent and the ’607 patent, Figures 3-5 of which are shown below:

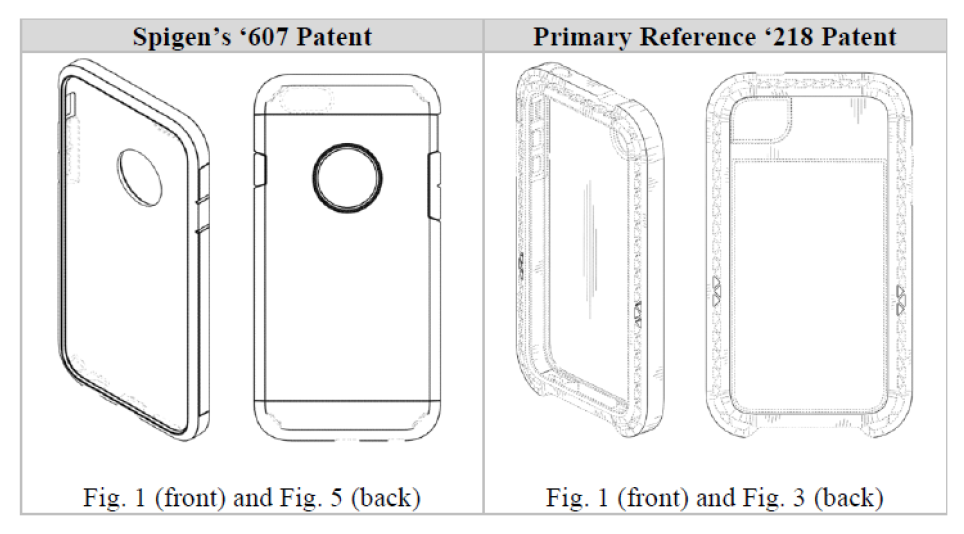

On February 13, 2017, Spigen sued Ultraproof for infringement of Spigen Design Patents in the United States District Court for the Central District of California. Ultraproof filed a motion for summary judgment of invalidity of Spigen Design Patents, arguing that the Spigen Design Patents were obvious as a matter of law in view of a primary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D729,218 (“the ’218 patent”) and a secondary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D772,209 (“the ’209 patent”). Spigen opposed the motion arguing that 1) the Spigen Design Patents were not rendered obvious by the primary and secondary reference as a matter of law; and 2) various underlying factual disputes precluded summary judgment. The district court held that as a matter of law, the Spigen Design Patents were obvious over the ’218 patent and the ’209 patent, and granted summary judgment of invalidity in favor of Ultraproof. Ultraproof then moved for attorneys’ fees, which the district court denied. Spigen appealed the district court’s obviousness determination, and Ultraproof cross-appealed the denial of attorneys’ fees.

On appeal, Spigen presented several arguments as to why the district court’s grant of summary judgment should be reversed. First, Spigen argued that there is a material factual dispute over whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference that precludes summary judgment. The CAFC agreed. The CAFC explained, citing Titan Tire Corp. v. Case New Holland, Inc., 566 F.3d 1372, 1380-81 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (quoting Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101 F.3d 100, 103 (Fed. Cir. 1996)) that the ultimate inquiry for obviousness “is whether the claimed design would have been obvious to a designer of ordinary skill who designs articles of the type involved,” which is a question of law based on underlying factual findings. Whether a prior art design qualifies as a “primary reference” is an underlying factual issue. The CAFC went on to explain that a “primary reference” is a single reference that creates “basically the same” visual impression, and for a design to be “basically the same,” the designs at issue cannot have “substantial differences in the[ir] overall visual appearance[s].” Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2012). A trial court must deny summary judgment if based on the evidence before the court, a reasonable jury could find in favor of the non-moving party. Here, the district court errored in finding that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” as the Spigen Design Patents despite there being “slight differences,” as a reasonable factfinder could find otherwise.

Spigen’s expert testified that the Spigen Design Patents and the ’218 patent are not “at all similar, let alone ‘basically the same.’” Spigen’s expert noted that the ’218 patent has the following features that are different from the Spigen Design Patents:

- unusually broad front and rear chamfers and side surfaces

- substantially wider surface

- lack of any outer shell-like feature or parting lines

- lack of an aperture on its rear side

- presence of small triangular elements illustrated on its chamfers

In contrast, Ultraproof argued that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” because of the presence of the following features:

- a generally rectangular appearance with rounded corners

- a prominent rear chamfer and front chamfer

- elongated buttons corresponding to the location of the buttons of the underlying phone

Ultraproof stated that the only differences were the “circular cutout in the upper third of the back surface and the horizontal parting lines on the back and side surfaces.”

Based on the competing evidence in the record, the CAFC found that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that the ’218 patent and the Spigen Design Patents are not basically the same. T

The CAFC determined that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference, and therefore, reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of invalidity and remanded the case for further proceedings.

Takeaway

When there is competing evidence in the record, the determination of whether a prior art reference creates “basically the same” visual impression, and therefore a proper primary reference, is a matter that cannot be decided at summary judgment.

A Patent Claim Is Not Indefinite If the Patent Informs the Relevant Skilled Artisan about the Invention’s Scope with Reasonable Certainty

| April 23, 2020

NEVRO CORP. v. BOSTON SCIENTIFIC

April 9, 2020

Before MOORE, TARANTO, and CHEN, Circuit Judges. MOORE, Circuit Judge

中文标题

权利要求的不确定性判定

中文摘要

内夫罗公司(Nevro)起诉波士顿科学公司和波士顿科学神经调节公司(合称波士顿科学)侵犯了内夫罗公司的七项专利。 内夫罗公司对地方法院的专利无效判决提出上诉。根据专利说明书及其申请历史,联邦巡回法院认定“paresthesia-free,” “configured to,” “means for generating,” 和 “therapy signal” 等术语并未使内夫罗公司的权利要求产生不确定性,因此撤销专利无效判决并发回重审。

小结

- 仅因其为功能用语或仅通过专利权利的诠释不能将功能性语言判定为不确定。

- 功能性语言的确定性重要体现在专利说明书中需要有解释或支持功能术语的相关结构,特别是侧重方法的专利申请,如果这些申请中存在着系统或设备的权利要求, 而这些系统或设备权利要求由方法的权利要求转化而来,对系统或设备的必要描述是需要的。1

- 不确定性的判定标准存在于是否权利要求通过说明书和申请历史以合理的确定性向本领域技术人员告知了本发明的范围。

注1:许多专利申请通常使用诸如“模块”(module)和“单元”(unit)的术语,并将方法权利要求转换为系统或设备的权利要求。但是,在说明书中如果没有相关的结构说明,由于不确定性,通常这些权利要求会被拒绝。因此,专利说明书中有必要对“模块”或“单元”进行必要的描述,例如电子、通讯及软件类的专利申请,可添加一些与通用处理器,集成芯片或现场可编程门阵列有关的描述,以定义“模块”或“单元”并描述相关功能。

Summary

Nevro Corporation (Nevro) sued Boston Scientific Corporation and Boston Scientific Neuromodulation Corporation (collectively, Boston Scientific) for infringement of eighteen claims across seven patents. Nevro Corporation appealed the district court’s judgment of invalidity. The Federal Circuit found that the terms “paresthesia-free,” “configured to,” “means for generating,” and “therapy signal” are not rendering the asserted claims indefinite in view of the specifications and prosecution history, vacating and remanding the district court’s judgment of claim invalidity.

Background

Nevro owns seven patents having method and system claims directed to high-frequency spinal cord stimulation therapy for inhibiting an individual pain. Nevro sued Boston Scientific in the Northern District of California for patent infringement related to U.S. Patent Nos. 8,359,102; 8,712,533; 8,768,472; 8,792,988; 9,327,125; 9,333,357; and 9,480,842.

In a joint claim construction and summary judgment order, the district court held twelve claims invalid as indefinite. Though six asserted claims survived and were found definite, the district court granted Boston Scientific noninfringement. On appeal, the Federal Circuit concluded the district court erred in holding indefinite the claims reciting the terms “paresthesia-free,” “configured to,” and “means for generating.” The Federal Circuit also found the district court erred in its construction of the term “therapy signal,” though determined not indefinite by the district court. The Federal Circuit, therefore, vacated and remanded the district court’s judgment of invalidity of claims 7, 12, 35, 37 and 58 of the ’533 patent, claims 18, 34 and 55 of the ’125 patent, claims 5 and 34 of the ’357 patent and claims 1 and 22 of the ’842 patent.

Discussion

I. “paresthesia-free”

Several of Nevro’s asserted claims relate to methods and systems comprising a means for generating therapy signals that are “paresthesia-free.” Claim 18 of the ’125 patent and Claim 1 of the ’472 patent recite as follow:

18. A spinal cord modulation system for reducing or eliminating pain in a patient, the system comprising:

means for generating a paresthesia-free therapy signal with a signal frequency in a range from 1.5 kHz to 100 kHz; and

means for delivering the therapy signal to the patient’s spinal cord at a vertebral level of from T9 to T12, wherein the means for delivering the therapy signal is at least partially implantable.

1. A method for alleviating patient pain or discomfort, without relying on paresthesia or tingling to mask the patient’s sensation of the pain, comprising:

implanting a percutaneous lead in the patient’s epidural space, wherein the percutaneous lead includes at least one electrode, and wherein implanting the percutaneous lead includes positioning the at least one electrode proximate to a target location in the patient’s spinal cord region and outside the sacral region;

implanting a signal generator in the patient; electrically coupling the percutaneous lead to the signal generator; and

programming the signal generator to generate and deliver an electrical therapy signal to the spinal cord region, via the at least one electrode, wherein at least a portion of the electrical therapy signal is at a frequency in a frequency range of from about 2,500 Hz to about 100,000 Hz.

The district court presented its findings based on extrinsic evidence that “[a]lthough the parameters that would result in a signal that does not create paresthesia may vary between patients, a skilled artisan would be able to quickly determine whether a signal creates paresthesia for any given patient.” While holding that the term “paresthesia-free” does not render the method claims indefinite, the district court held indefiniteness regarding the asserted system and device claims. The Federal Circuit disagreed the indefiniteness holdings because the test of indefiniteness should be simply based on whether a claim “inform[s] those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.” The Federal Circuit states that the district court applied the wrong legal standard and the test for indefiniteness is not whether infringement of the claim must be determined on a case-by-case basis.

The Federal Circuit states that “paresthesia-free,” a functional term defined by what it does rather than what it is, does not inherently render it indefinite. Furthermore, the Federal Circuit instructs that

i. functional language can “promote[] definiteness because it helps bound the scope of the claims by specifying the operations that the [claimed invention] must undertake.” Cox Commc’ns, 838 F.3d at 1232.

ii. the ambiguity inherent in functional terms may be resolved where the patent “provides a general guideline and examples sufficient to enable a person of ordinary skill in the art to determine the scope of the claims.” Enzo Biochem. Inc. v. Applera Corp., 599 F.3d 1325, 1335 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

II. “configured to”

Nevro’s asserted claim 1 of the ’842 patent relates to a spinal cord modulation system, which recites:

1. A spinal cord modulation system comprising:

a signal generator configured to generate a therapy signal having a frequency of 10 kHz, an amplitude up to 6 mA, and pluses having a pulse width between 30 microseconds and 35 microseconds; and

an implantable signal delivery device electrically coupleable to the signal generator and configured to be implanted within a patient’s epidural space to deliver the therapy signal from the signal generator the patient’s spinal cord.

The district court held indefiniteness because it determined that “configured to” is susceptible to meaning one of two constructions: “(1) the signal generator, as a matter of hardware and firmware, has the capacity to generate the described electrical signals (either without further programing or after further programming by the clinical programming software); or (2) the signal generator has been programmed by the clinical programmer to generate the described electrical signals.”

The Federal Circuit pointed out that “the test [of indefiniteness] is not merely whether a claim is susceptible to differing interpretations” because “such a test would render nearly every claim term indefinite so long as a party could manufacture a plausible construction.” Further, the Federal Circuit states that the test for indefiniteness is whether the claims, viewed in light of the specification and prosecution history, “inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.” Nautilus, 572 U.S. at 910. (emphasis added).

The specifications of the asserted patents and prosecution history, indeed, help Nevro win the argument on “configured” means. Nevro’s asserted patents not only recites that “the system is configured and programmed to,” but also Nevro agreed with the examiner that “configured” means “programmed” as opposed to “programmable.” The limitation specifies the interpretation of the term “configured” and leads to this favorable decision towards Nevro. The “programmed” and “programmable” may sound similar. However, “programmable” would be appliable to a general machine, since any general signal generator would have the capacity to generate the described signals. The term “programmed” sets out its specific settings of the signal generator and limits such broad interpretation.

III. “means for generating”

Several asserted claims of the ‘125 patent recite “means for generating,” in which claim 18 recites as follow:

18. A spinal cord modulation system for reducing or eliminating pain in a patient, the system comprising:

means for generating a paresthesia-free therapy signal with a signal frequency in a range from 1.5 kHz to 100 kHz; and

means for delivering the therapy signal to the patient’s spinal cord at a vertebral level of from T9 to T12, wherein the means for delivering the therapy signal is at least partially implantable.

Nevro argued that the specification discloses a signal generator as the structure. The Federal Circuit agreed with Nevro and explained the difference comparing a general-purpose computer or processor. If the identified structure is a general-purpose computer or processor, it does require a specific algorithm. A signal or pulse generator is not considered as a general-purpose computer or processor, since it has the structure for the claimed “generating” function. Further, “the specification teaches how to configure the signal generators to generate and deliver the claimed signals using the recited parameters, clearly linking the structure to the recited function.” Hence, the Federal Circuit held that the district court erred in holding indefinite claims with the terms “means for generating.”

The terms such as “module” and “unit” are commonly used in many patent applications to convert method claims to system or device claims in electronic applications. However, without structural description in the specification, such claims are usually rejected due to indefiniteness. Hence, some may add some description related to general-purpose processors, integrated chips, or field-programmable gate arrays to define the “module” or “unit” and describe the functions.

IV. “therapy signal”

The Federal Circuit agreed that claims reciting a “therapy signal” are not indefinite, but held that the district court incorrectly construed the term. The Federal Circuit reiterated the context of the specification and prosecution history for understanding the words of a claim. It stated that “[t]he words of a claim are generally given their ordinary and customary meaning as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art when read in the context of the specification and prosecution history.” Thorner v. Sony Comput. Entm’t Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

Boston Scientific argued that the asserted claims reciting a “therapy signal” are indefinite because “two signals with the same set of characteristics (e.g., frequency, amplitude, and pulse width) may result in therapy in one patient and no therapy in another.” The Federal Circuit noted that “the fact that a signal does not provide pain relief in all circumstances does not render the claims indefinite.” Geneva, 349 F.3d at 1384.

Takeaway

- Functional language won’t be held indefinite simply for that reason or simply by interpreted in the claims.

- It is of importance to describe a related structure to support the functional terms in the specification, especially for applications having system or device claims converted from method claims.

- The test for indefiniteness is whether the claims, viewed in light of the specification and prosecution history, “inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.” Nautilus, 572 U.S. at 910.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 112 > indefiniteness > Mean-Plus-Function > reasonable certainty

For Biotech, “Method of Preparation” Claims May Survive §101

| April 15, 2020

Illumina, Inc. v. Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc.

March 17, 2020

Lourie, Moore, and Reyna (Opinion by Lourie; Dissent by Reyna)

Summary

In a patent infringement litigation between the same parties that were involved in the earlier case, Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., 788 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (diagnostic patent deemed patent ineligible under 35 U.S.C. §101), the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“Federal Circuit”) found the claimed “method of preparation” of a fraction of cell-free fetal DNA (“cff-DNA”) enriched in fetal DNA to be patent eligible, reversing the district court’s grant of summary judgment of patent ineligibility. A dissent by J. Reyna (author of the earlier Ariosa decision) asserts that there is nothing new and useful in the claims, other than the discovery that cff-DNA tends to be shorter than cell-free maternal DNA, and that use of known laboratory techniques and commercially available testing kits to isolate the naturally occurring shorter cff-DNA does not make the claims patent eligible.

Details

Illumina and Sequenom (collectively, “Illumina”) appealed a

summary judgment ruling of patent ineligibility by the United States District

Court for the Northern District of California.

The two patents at issue, USP 9,580,751 (the ‘751 patent) and USP

9,738,931 (the ‘931 patent), are unrelated to the diagnostic patent held

ineligible in the 2015 Ariosa decision. While the earlier litigated patent claimed a

method for detecting the small fraction of cff-DNA in the plasma and serum of a

pregnant woman that were previously discarded as medical waste, the present

‘751 and ‘931 patents claim methods for preparing a fraction of cff-DNA that is

enriched in fetal DNA. A problem with

maternal plasma is that it was difficult, if not impossible, to determine fetal

genetic markers (e.g., for certain diseases) because the proportion of circulatory

extracellular fetal DNA in maternal plasma was tiny as compared to the majority

of it (>90%) being circulatory extracellular maternal DNA. The inventor’s

“surprising” discovery was that the majority of circulatory extracellular fetal

DNA has a relatively small size of approximately 500 base pairs or less, as

compared to the larger circulatory extracellular maternal DNA. With this discovery, they developed the

following claimed methods for preparing a DNA fraction that separated fetal DNA

from maternal DNA from the maternal plasma and serum, to create a DNA fraction

enriched with fetal DNA.

‘931 Patent:

1. A method for preparing a deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fraction from a pregnant human female useful for analyzing a genetic locus involved in a fetal chromosomal aberration, comprising:

(a) extracting DNA from a substantially cell-free sample of blood plasma or blood serum of a pregnant human female to obtain extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA fragments;

(b) producing a fraction of the DNA extracted in (a) by:

(i) size discrimination of extracellular circulatory DNA fragments, and

(ii) selectively removing the DNA fragments greater than approximately 500 base pairs, wherein the DNA fraction after (b) comprises a plurality of genetic loci of the extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA; and

(c) analyzing a genetic locus in the fraction of DNA produced in (b).

‘751 Patent:

1. A method, comprising:

(a) extracting DNA comprising maternal and fetal DNA fragments from a substantially cell-free sample of blood plasma or blood serum of a pregnant human female;

(b) producing a fraction of the DNA extracted in (a) by:

(i) size discrimination of extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA fragments, and

(ii) selectively removing the DNA fragments greater than approximately 300 base pairs, wherein the DNA fraction after (b) comprises extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA fragments of approximately 300 base pairs and less and a plurality of genetic loci of the extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA fragments; and

(c) analyzing DNA fragments in the fraction of DNA produced in (b).

The Federal Circuit had consistently found diagnostic claims patent ineligible (as directed to natural phenomenon) (Athena Diagnostics, Inc. v. Mayo Collaborative Servs., LLC, 927 F.3d 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2019); Athena Diagnostics, Inc. v. Mayo Collaborative Servs., LLC, 915 F.3d 743 (Fed. Cir. 2019); Cleveland Clinic Found. v. True Health Diagnostics LLC, 859 F.3d 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2017)). In contrast, the Federal Circuit had also held that method of treatment claims are patent eligible (Endo Pharm. Inc. v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc., 919 F.3d 1347 (Fed. Cir. 2019); Natural Alternative Int’l, Inc. v. Creative Compounds, LLC, 918 F.3d 1338 (Fed. Cir. 2019); and Vanda Pharm. Inc. v. West-Ward Pharm. Int’l Ltd., 887 F.3d 1117 (Fed. Cir. 2018)). However, this is not a diagnostic case, nor a method of treatment case. This is a method of preparation case – which the Federal Circuit found to be patent eligible.

The natural phenomenon at issue is that cell-free fetal DNA tends to be shorter than cell-free maternal DNA in the mother’s bloodstream. However, under the Alice/Mayo Step 1, the Federal Circuit held that these claims are not directed to a natural phenomenon. Instead, the claims are directed to a method that utilizes that phenomenon. The claimed method recites specific process steps – size discrimination and selective removal of DNA fragments above a specified size threshold. These process steps change the composition of the normal maternal plasma or serum, creating a fetal DNA enriched mixture having a higher percentage of cff-DNA fraction different from the naturally occurring fraction in the normal mother’s blood. “Thus, the process achieves more than simply observing that fetal DNA is shorter than maternal DNA or detecting the presence of that phenomenon.”

In distinguishing the earlier Ariosa case, the Federal Circuit stated, “the claims do not merely cover a method for detecting whether a cell-free DNA fragment is fetal or maternal based on its size.”

In distinguishing the Supreme Court decision in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. 576 (2013), the Federal Circuit noted that the “Supreme Court in Myriad expressly declined to extend its holding to method claims reciting a process used to isolate DNA” and that “in Myriad, the claims were ineligible because they covered a gene rather than a process for isolating it.” Here, the method “claims do not cover cell-free fetal DNA itself but rather a process for selective removal of non-fetal DNA to enrich a mixture in fetal DNA.” This is the opposite of Myriad.

As for whether the techniques for size discrimination and selective removal of DNA fragments were well-known and conventional, those considerations are relevant to the Alice/Mayo Step 2 analysis, or to 102/103 issues – not for Alice/Mayo Step 1. The majority concluded patent eligibility under Step 1 and did not proceed to Step 2.

J. Reyna’s dissent focused on the claims being directed to a natural phenomenon because the “only claimed advance is the discovery of that natural phenomenon.” In particular, referring to a “string of cases reciting process claims” since 2016, the “directed to” inquiry under Alice/Mayo Step 1 asks “whether the ‘claimed advance’ of the patent ‘improves upon a technological process or is merely an ineligible concept.’” citing Athena, 915 F.3d at 750 and Genetic Techs., 818 F.3d at 1375. “Here, the claimed advance is merely the inventors’ ‘surprising[]’ discovery of a natural phenomenon – that cff-DNA tends to be shorter than cell-free maternal DNA in a mother’s bloodstream.” J. Reyna criticizes the majority for ignoring the “claimed advance” inquiry altogether.

Under the claimed advance inquiry, one looks to the written description. Here, the written description identifies the use of well-known and commercially available tools/kits to perform the claimed method. Checking for 300 and 500 base pairs using commercially available DNA size markers and kits does not constitute any “advance.” There is no improvement in the underlying DNA processing technology, but for checking the natural phenomenon of sizes indicative of cff-DNA.

J. Reyna also criticized the majority’s “change in the composition of the mixture” justification. “A process that merely changes the composition of a sample of naturally occurring substances, without altering the naturally occurring substances themselves, is not patent eligible.” Here, one begins and ends with the same naturally occurring substances – cell-free fetal DNA and cell free maternal DNA. There is no creation or alteration of any genetic information encoded in the cff-DNA. Therefore, the claims are directed to a natural phenomenon under Alice/Mayo Step 1.

J. Reyna also found no inventive concept under Alice/Mayo Step 2.

Take Away

- Until there is an en banc rehearing or a Supreme Court review of this case, this case is an example of a patent eligible method of preparation claim.

- For defendants, the “claimed advance” inquiry could help sink a claimed method under Alice/Mayo Step 1.

Tags: 101 > biotech > diagnostics > eligibility > Mayo/Alice Test > preparation > treatment

FACEBOOK’S IPRs CAN’T FRIEND EACH OTHER

| April 10, 2020

FACEBOOK, INC. v. WINDY CITY INNOVATIONS, LLC.

March 18, 2020

Prost, Plager and O’Malley (Opinion by Prost)

Summary: Plaintiff/Patent Holder Windy Citysuccessfully cross-appealed against Facebook on the issue of improper joinder of IPRs under 35 U.S.C. § 315(c). Facebook had filed IPRs within one year of Windy City’s District Court complaint and then joined later filed IPRs adding new claims. The PTAB had allowed the joinder. The CAFC vacated the Board’s joinder finding that Facebook could not join their own already filed IPRs.

Background:

In June 2016, exactly one year after being served with Windy City’s complaint for infringement of four patents related to methods for communicating over a computer-based net-work, Facebook timely petitioned for inter partes review (“IPR”) of several claims of each patent. At that time, Windy City had not yet identified the specific claims it was asserting in the district court proceeding. The four patents totaled 830 claims. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) instituted IPRs of each patent.

In January 2017, after Windy City had identified the claims it was asserting in the district court litigation, Facebook filed two additional petitions for IPR of additional claims of two of the patents. Facebook concurrently filed motions for joinder to the already instituted IPRs on those patents. By the time of filing the new IPRs, the one-year time bar of §315(b) had passed. The Board nonetheless instituted Facebook’s two new IPRs, and granted Facebook’s motions for joinder.

The Board agreed with Facebook that Windy City’s district court complaint generally asserting the “claims” of the asserted patents “cannot reasonably be considered an allegation that Petitioner infringes all 830 claims of the several patents asserted.” The Board therefore found that Facebook could not have reasonably determined which claims were asserted against it within the one-year time bar. Once Windy City identified the asserted claims after the one-year time bar, the Board found that Facebook did not delay in challenging the newly asserted claims by filing the second petitions with the motions for joinder.

The Board found that Facebook had shown by a preponderance of the evidence that some of the challenged claims are unpatentable, many of these claims had only been challenged in the later filed and joined IPRs. Facebook appealed and Windy City cross-appealed on the Board’s obviousness findings. Further, Windy City also challenged the Board’s joinder decisions allowing Facebook to join its new IPRs to its existing IPRs and to include new claims in the joined proceedings. Windy City’s cross-appeal on the joinder issue is addressed here.

Discussion:

In its cross-appeal, Windy City argued that the Board’s decisions granting joinder were improper on the basis that 35 U.S.C. § 315(c): (1) does not permit a person to be joined as a party to a proceeding in which it was already a party (“same-party” joinder); and (2) does not permit new issues to be added to an existing IPR through joinder (“new issue” joinder), including issues that would otherwise be time-barred.

Sections 315(b) and (c) recite:

(b) Patent Owner’s Action. —An inter partes review may not be instituted if the petition requesting the proceeding is filed more than 1 year after the date on which the petitioner, real party in interest, or privy of the petitioner is served with a complaint alleging infringement of the patent. The time limitation set forth in the preceding sentence shall not apply to a request for joinder under subsection (c).

(c) Joinder. —If the Director institutes an inter partes review, the Director, in his or her discretion, may join as a party to that inter partes review any person who properly files a petition under section 311 that the Director, after receiving a preliminary response under section 313 or the expiration of the time for filing such a response, determines warrants the institution of an inter partes review under section 314.

The CAFC noted that §315(b) articulates the time-bar for when an IPR “may not be instituted.” 35 U.S.C. §315(b). But §315(b) includes a specific exception to the time bar, namely “[t]he time limitation . . . shall not apply to a request for joinder under subsection (c).”

Regarding the propriety of Facebooks joinder, the Court held the plain language of §315(c) allows the Director “to join as a party [to an already instituted IPR] any person” who meets certain requirements. However, when the Board instituted Facebook’s later petitions and granted its joinder motions, the Board did not purport to be joining anyone as a party. Rather, the Board understood Facebook to be requesting that its later proceedings be joined to its earlier proceedings. The CAFC concluded that the Boards interpretation of §315(c) was incorrect because their decision authorized two proceedings to be joined, rather than joining a person as a party to an existing proceeding.

Section 315(c) authorizes the Director to “join as a party to [an IPR] any person who” meets certain requirements, i.e., who properly files a petition the Director finds warrants the institution of an IPR under § 314. No part of § 315(c) provides the Director or the Board with the authority to put two proceedings together. That is the subject of § 315(d), which provides for “consolidation,” among other options, when “[m]ultiple proceedings” involving the patent are before the PTO.35 U.S.C. § 315.

The Court went on to explain that the clear and unambiguous language of § 315(c) confirms that it does not allow an existing party to be joined as a new party, noting that subsection (c) allows the Director to “join as a party to [an IPR] any person who” meets certain threshold requirements. They noted that it would be an extraordinary usage of the term “join as a party” to refer to persons who were already a party. Finding the phrase “join as a party to a proceeding” on its face limits the range of “person[s]” covered to those who, in normal legal discourse, are capable of being joined as a party to a proceeding (a group further limited by the own-petition requirements), and an existing party to the proceeding is not so capable.

Regarding the second issue raised by Windy City that the Joinder cannot include newly raised issues, the CAFC found the language in §315(c) does no more than authorize the Director to join 1) a person 2) as a party, 3) to an already instituted IPR. Finding this language does not authorize the joined party to bring new issues from its new proceeding into the existing proceeding, particularly when those new issues are other-wise time-barred.

The Court noted that under the statute, the already-instituted IPR to which a person may join as a party is governed by its own petition and is confined to the claims and grounds challenged in that petition.

In reaching these conclusions, the Court did acknowledge the rock and hard place Facebook is left in.

We do not disagree with Facebook that the result in this particular case may seem in tension with one of the AIA’s objectives for IPRs “to provide ‘quick and cost effective alternatives’ to litigation in the courts.” [Citations omitted] Indeed, it is fair to assume that when Congress imposed the one-year time bar of § 315(b), it did not explicitly contemplate a situation where an accused infringer had not yet ascertained which specific claims were being asserted against it in a district court proceeding before the end of the one-year time period. We also recognize that our analysis here may lead defendants, in some circumstances, to expend effort and expense in challenging claims that may ultimately never be asserted against them.

However, the Court gave little remedy to bearing an enormous “effort and expense” of filing IPRs to 830 claims, asserting that they are bound by the unambiguous nature of the statute.

Petitioners who, like Facebook, are faced with an enormous number of asserted claims on the eve of the IPR filing deadline, are not without options. As a protective measure, filing petitions challenging hundreds of claims remains an available option for accused infringers who want to ensure that their IPRs will challenge each of the eventually asserted claims. An accused infringer is also not obligated to challenge every, or any, claim in an IPR. Accused infringers who are unable or unwilling to challenge every claim in petitions retain the ability to challenge the validity of the claims that are ultimately asserted in the district court. Accused infringers who wish to protect their option of proceeding with an IPR may, moreover, make different strategy choices in federal court so as to force an earlier narrowing or identification of asserted claims. Finally, no matter how valid, “policy considerations cannot create an ambiguity when the words on the page are clear.” SAS, 138 S. Ct. at 1358. That job is left to Congress and not to the courts.

Hence, the CAFC concluded that the clear and unambiguous language of §315(c) does not authorize same-party joinder, and also does not authorize joinder of new issues, including issues that would otherwise be time-barred. As a result, they vacated the Board’s decisions on all claims which were asserted in the later filed IPRs.

Take Away: A loop-hole between the one-year time bar, joinder statute for IPRs and District Court timing potentially gives a Plaintiff/Patent holder the ability to render an IPR more cost inefficient to a Defendant/Petitioner. By not identifying the claims to be asserted within one year of filing a patent infringement complaint, the patent holder can place a large burden on filing an IPR. Plaintiffs/Patent holders can strategize to assert infringement ambiguously to a prohibitive number of claims early in a District Court proceeding. Defendants will need to attempt to counter such a strategy by requesting District Courts to force Plaintiffs to identify the specific claims which will be asserted within one year of filing the complaint.