WHEN IS PRIOR ART ANALOGOUS?

| November 29, 2019

Airbus v. Firepass

November 8, 2019

Lourie, Moore, and Stoll

Summary:

To determine whether a reference is “analogous prior art,” one must first ask whether the reference is from the same “field of endeavor” as claimed invention. If not, one must ask whether the reference is “reasonably pertinent” to the particular problem addressed by the claimed invention.

As phrased by the CAFC here, a reference is “reasonably pertinent” if

an ordinarily skilled artisan would reasonably have consulted in seeking a solution to the problem that the inventor was attempting to solve, [so that] the reasonably pertinent inquiry is inextricably tied to the knowledge and perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention.

Thus, one should consider (i) in which areas one skilled in the art would reasonably look, and (ii) what that skilled person would reasonably search for, in trying to address the problem faced by the inventor. Accordingly, courts or examiners should consider evidence cited by the parties or the applicant that demonstrates “the knowledge and perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention.”

If a reference fails both the “field of endeavor” and the “reasonably pertinent” tests, it is not analogous prior art and not available for an obviousness rejection.

Background:

Challenger Airbus filed an inter partes reexamination against a patent owned by Firepass. The examiner rejected the claims at issue here as being obvious over the Kotliar reference in view of other prior art. The examiner also rejected other claims, not in issue here, as being obvious over Kotliar in view of four prior references (Gustafsson, the 1167 Report, Luria, and Carhart).

The claimed invention is an enclosed fire prevention and suppression system (for instance, computer rooms, military vehicles, or spacecraft), which extinguishes fire with an atmosphere of breathable air. The inventor found that a low-oxygen atmosphere (16.2% or slightly lower), maintained at normal pressure, would inhibit fire and yet be breathable by humans. Normal pressure is maintained by added nitrogen gas.

The patent contains the following independent claim that was added during the reexamination:

A system for providing breathable fire-preventive and fire suppressive atmosphere in enclosed human-occupied spaces, said system comprising:

an enclosing structure having an internal environment therein containing a gas mixture which is lower in oxygen content than air outside said structure, and an entry communicating with said internal environment;

an oxygen-extraction device having a filter, an inlet taking in an intake gas mixture and first and second outlets, said oxygen-extraction device being a nitrogen generator, said first outlet transmitting a first gas mixture having a higher oxygen content than the intake gas mixture and said second outlet transmitting a second gas mixture having a lower oxygen content than the intake gas mixture;

said second outlet communicating with said internal environment and transmitting said second mixture into said internal environment so that said second mixture mixes with the atmosphere in said internal environment;

said first outlet transmitting said first mixture to a location where it does not mix with said atmosphere in said internal environment;

said internal environment selectively communicating with the outside atmosphere and emitting excessive internal gas mixture into the outside atmosphere;

said intake gas mixture being ambient air taken in from the external atmosphere outside said internal environment with a reduced humidity; and

a computer control for regulating the oxygen con-tent in said internal environment.

The Board of Appeals reversed the examiner’s rejection, finding that Kotliar is not analogous prior art. The Board stated that the examiner had not articulated a “rational underpinning that sufficiently links the problem [addressed by the claimed invention] of fire suppression/prevention confronting the inventor” to the disclosure of Kotliar, “which is directed to human therapy, wellness, and physical training.” Significantly, the Board did not consider Airbus’ argument that “breathable fire suppressive environments [were] well-known in the art,” stating that the four references, relied on by Airbus, were not used by the examiner for the rejection of the claims in issue here.

Discussion:

The CAFC began its analysis by citing the “field of endeavor” and the “reasonably pertinent” tests mentioned above.

With respect to “field of endeavor,” the CAFC agreed with the Board. The Court explained that the disclosure of the references is the primary focus, but that courts and examiners must also consider each reference’s disclosure in view of the “the reality of the circumstances” and “weigh those circumstances from the vantage point of the common sense likely to be exerted by one of ordinary skill in the art in assessing the scope of the endeavor.”

Here, the Board found that the “field of endeavor” for the patent to be “devices and methods for fire prevention/suppression,” citing the preamble of the claim, the title and specification of the patent. Kotliar, on the other hand, concerns “human therapy, wellness, and physical training,” based on its title and specification. The Board concluded that Kotliar was outside the field of endeavor of the claimed invention, particularly in view of the fact that Kotliar never mentions “fire.”

The CAFC found that the Board’s conclusion is supported by substantial evidence.

Airbus argued that the Board should have considered the four references—Gustafsson, the 1167 Report, Luria, and Carhart—to which show that “a POSA would have known and appreciated that the breathable hypoxic air produced by Kotliar is fire-preventative and fire-suppressive, even though Kotliar does not state this” (emphasis in original). The CAFC disagreed, stating that Board’s failure to consider these references, if error, was harmless error. The CAFC explained that

a reference that is expressly directed to exercise equipment and fails to mention the word “fire” even a single time—falls within the field of fire prevention and suppression. Such a conclusion would not only defy the plain text of Kotliar, it would also defy “common sense” and the “reality of the circumstances” that a factfinder must consider in determining the field of endeavor.

The CAFC, however, came to the opposite conclusion with respect to the “reasonably pertinent” test. As with the “field of endeavor” test, the Board had failed to consider the four references. The CAFC found that this was a mistake.

In determining whether a reference is “reasonably pertinent” to the particular problem addressed by the claimed invention, for assessing whether a reference is analogous prior art, the court or the examiner should consider (i) in which areas one skilled in the art would reasonably look, and (ii) what that skilled person would reasonably search for, in trying to address the problem faced by the inventor. A court or examiner should therefore consider evidence cited by the parties or the applicant that demonstrates “the knowledge and perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention.”

Here, the four references are relevant to the question of whether one skilled in the art of fire prevention and suppression would have reasonably consulted references relating to normal pressure, low-oxygen atmospheres to address the problem of preventing and suppressing fires in enclosed environments. As stated above, the four references—Gustafsson, the 1167 Report, Luria, and Carhart—to which show that “a POSA would have known and appreciated that the breathable hypoxic air produced by Kotliar is fire-preventative and fire-suppressive, even though Kotliar does not state this” (emphasis in original). These references, the CAFC stated, could therefore lead a court or an examiner to conclude that one skilled in the field of fire prevention and suppression would have looked to Kotliar for its disclosure of a hypoxic room, even though Kotliar itself is outside the field of endeavor.

The CAFC therefore vacated the Board’s decision and remanded the case for the Board to consider whether Kotliar is analogous prior art in view of the four references.

Takeaway:

In resolving the “reasonably pertinent” test, courts and examiners must look at all the evidence of record.

Preamble Reciting a Travel Trailer is a Structural Limitation – Avoiding Assertions of Intended Use

| November 26, 2019

In Re: David Fought, Martin Clanton.

November 4, 2019

Newman, Moore and Chen

Summary

This decision provides an excellent example of when a limitation in a preamble is given patentable weight. The decision also illustrates arguments which will not be successful. The Federal Circuit held that not only was the preamble limiting, but also held that a “travel trailer” is considered a specific type of recreation vehicle having structural distinctions.

Background

The patent application contains two independent claims:

1. A travel trailer having a first and second compartment therein separated by a wall assembly which is movable so as to alter the relative dimensions of the first and second compartments without altering the exterior appearance of the travel trailer.

2. A travel trailer having a front wall, rear wall, and two side walls with a first and a second compartment therein, those compartments being separated by a wall assembly, the wall assembly having a forward wall and at least one side member,

the side member being located adjacent to and movable in parallel with respect to a side wall of the trailer, and

the wall assembly being moved along the longitudinal length of the trailer by drive means positioned between the side member and the side wall. (Emphasis added)

The examiner rejected claim 1 as anticipated by a reference describing a conventional truck trailer such as a refrigerated trailer, and rejected claim 2 as anticipated over another reference describing a bulkhead for shipping compartments. The applicants appealed the rejections by (1) arguing that the claims do not have a preamble, (2) arguing that a travel trailer is a type of recreational vehicle, as supported by extrinsic evidence, and (3) arguing that the Examiner erred by rejecting the claims without addressing the level of ordinary skill.

Discussion

The CAFC reviewed the Board’s legal conclusions (involving claim construction) de novo and reviewed the factual findings (involving the extrinsic evidence) for substantial evidence.

The effect of a preamble is treated as a claim construction issue. The CAFC was not persuaded by the argument that the claims do not have a preamble because a traditional transitional phrase such as “comprising” was not used. The CAFC explained that although a traditional transitional phrase was not used, the word “having” performs the role of a transitional phrase. As such, this argument was not persuasive.

The next argument, however, was found persuasive. In particular, the CAFC has repeatedly held that a preamble is limiting when it serves as antecedent basis for a term appearing in the body of the claim. See, e.g., C.W. Zumbiel Co., 702 F.3d at 1385; Bell Commc’ns Re-search, Inc. v. Vitalink Commc’ns Corp., 55 F.3d 615, 620–21 (Fed. Cir. 1995); Electro Sci. Indus., Inc. v. Dynamic De-tails, Inc., 307 F.3d 1343, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2002); Pacing Techs., LLC v. Garmin Int’l, Inc., 778 F.3d 1021, 1024 (Fed. Cir. 2015). As seen in claims 1 and 2 above, each claim refers back to the preamble.

With respect to the meaning of “travel trailer”, the PTAB quoted relevant portions of the extrinsic evidence:

“Recreational vehicles” or “RVs,” as referred to herein, can be motorized or towed, but in general have a living area which provides shelter from the weather as well as personal conveniences for the user, such as bathroom(s), bedroom(s), kitchen, dining room, and/or family room. Each of these rooms typically forms a separate compartment within the vehicle . . . . A towed recreational vehicle is generally referred to as a “travel trailer.”

Probably the single most-popular class of towable RV is the Travel Trailer. Spanning 13 to 35 feet long, travel trailers are designed to be towed by cars, vans, and pickup trucks with only the addition of a frame or bumper mounted hitch. Single axles are common, but dual and even triple axles may be found on larger units to carry the load.

In regard to the meaning of “travel trailer”, the extrinsic evidence shows that “travel trailer” connotes a specific structure of towability which is not an intended use. In addition, the extrinsic evidence shows that recreational vehicles and travel trailers have living space rather than cargo space, which also is not an intended use. As such, “travel trailer” is a specific type of recreational vehicle and the term is a structural limitation.

The CAFC thus concludes:

“There is no dispute that if “travel trailer” is a limitation, Dietrich and McDougal, which disclose cargo trailers and shipping compartments, do not anticipate. Just as one would not confuse a house with a warehouse, no one would confuse a travel trailer with a truck trailer.”

The argument that the PTAB erred for failing to explicitly state the level of ordinary skill was a loser:

“Unless the patentee places the level of ordinary skill in the art in dispute and explains with particularity how the dispute would alter the outcome, neither the Board nor the examiner need articulate the level of ordinary skill in the art. We assume a proper determination of the level of ordinary skill in the art as required by Phillips.”

Takeaways

- The preamble is limiting when it serves as antecedent basis for a term appearing in the body of the claim.

- A term in the preamble can be construed as a structural limitation and not merely a statement of intended use when the evidence supports such meaning.

Is a claim limitation functional or merely an intended use?

| November 21, 2019

Quest USA Corp. v. PopSockets LLC (Patent Trial and Appeal Board)

August 12, 2019

Zado, Kaiser and Margolies (Administrative Patent Judges)

Summary:

This case is a Final Written Decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board of an inter partes review (“IPR”) filed by Quest USA Corp (“Petitioner”) against U.S. Patent No. 8,560,031 owned by PopSockets LLC (“Patent Owner”). One issue in the IPR was whether a limitation in claim 9 of the ‘031 patent is a functional limitation that should be given patentable weight or whether the limitation is just an intended use that is not given patentable weight. The noted limitation is a securing element “for attaching the socket to the back of the portable media player.” As part of its finding that the claims are anticipated, the PTAB held that the noted limitation is an intended use and that Grinfas is inherently capable of satisfying the noted limitation.

Details:

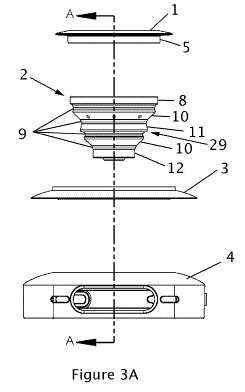

The ‘031 patent is to an “Extending Socket for Portable Media Player” and describes extending sockets for attaching to the back of a portable media player or media player case. The extending sockets can be used for, e.g., storing headphone cords and preventing cords from tangling. Figure 3A from the ‘031 patent is provided:

Claims 9-11, 16 and 17 of the ‘031 patent are at issue in this IPR. Claim 9 is provided below, and the limitation relevant to this summary is highlighted:

9. A socket for attaching to a portable media player or to a portable media player case, comprising:

[a] a securing element for attaching the socket to the back of the portable media player or portable media player case; and

[b] an accordion forming a tapered shape connected to the securing element, the accordion capable of extending outward generally along its [axis] from the portable media player and retracting back toward the portable media player by collapsing generally along its axis; and

[c] a foot disposed at the distal end of the accordion.

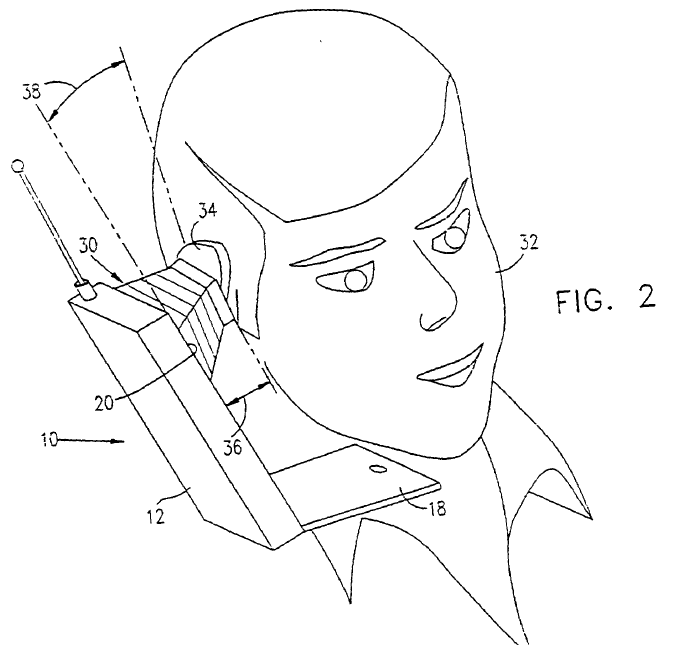

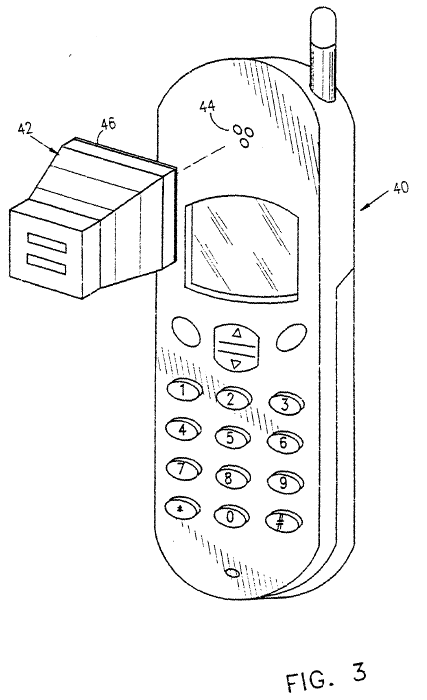

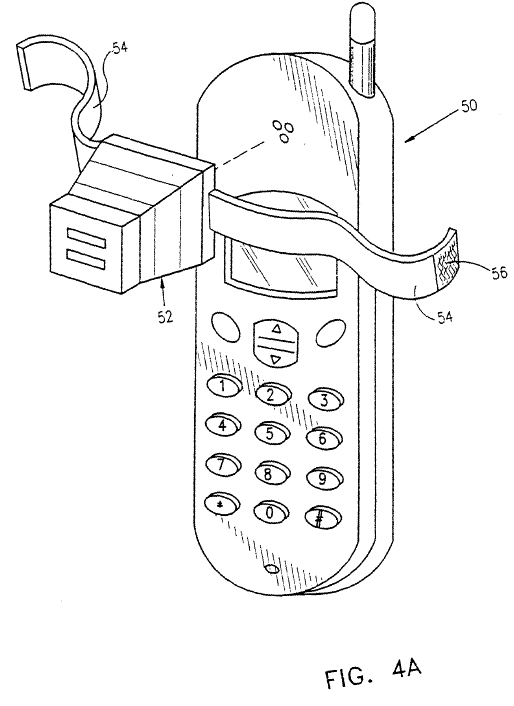

Petitioner asserted that claims 9-11, 16 and 17 are anticipated by Grinfas (UK Patent Application GB 2 316 263 A). Grinfas discloses a collapsible sound conduit for attaching to a cellular telephone. The idea of Grinfas is to provide a spaced distance between the telephone and a user’s head to reduce radiation exposure. Figures 2, 3 and 4A of Grinfas are provided below:

Grinfas discloses using an adhesive pad or straps to attach the collapsible sound conduit to the asserted media player. Patent Owner did not dispute that Grinfas discloses “a securing element” for attaching the socket to the earpiece of a telephone. However, Patent Owner, attempting to characterize the limitation as functional, argued that Grinfas does not disclose a securing element “for attaching the socket to the back of the portable media player” as recited in claim 9.

The PTAB stated that the issue is whether the noted limitation recites “1) functional language that must be given patentable weight, or 2) an intended use that is not limiting.” The PTAB also provided these two legal principles:

(1) “Where all structural elements of a claim exist in a prior art product, and that prior art product is capable of satisfying all functional or intended use limitations, the claimed invention is nothing more than an unpatentable new use for an old product.” Bettcher Indus., Inc. v. Bunzl USA, Inc., 661 F.3d 629, 654 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

(2) “[A] prior art reference may anticipate or render obvious an apparatus claim—depending on the claim language—if the reference discloses an apparatus that is reasonably capable of operating so as to meet the claim limitations, even if it does not meet the claim limitations in all modes of operation.” ParkerVision, 903 F.3d at 1361.

Petitioner argued that the “for attaching” language merely recites an intended use and is not entitled to patentable weight and that the structures disclosed in Grinfas are inherently capable of attaching to the back of a phone or phone case. The PTAB agreed with Petitioner that Grinfas is inherently capable of performing the function of attaching the asserted socket to the back of the portable media player. They relied on expert testimony that stated that the adhesive pad described in Grinfas has an adhesive that would stick to either side of the telephone, and that the straps could be used to fasten the sound conduit to either side of a telephone.

Patent Owner did not dispute that Grinfas’s securing elements are inherently capable of attaching the collapsible sound conduit to the back of a telephone. Patent Owner argued that Grinfas does not actually disclose the function of attaching to the back of a phone, and that the expert failed to provide evidence that the claimed function is necessarily present in Grinfas. The PTAB stated that Petitioner is not required to show the claimed function is actually performed or must be performed.

Patent Owner further argued that the “for attaching the socket to the back” limitation is entitled to patentable weight “because … this language recites a fundamental characteristic without which the invention would be of little use.” However, the PTAB looked at the specification and the prosecution history and concluded that the limitation does not recite a fundamental characteristic without which the invention would be of little use. The PTAB said that the specification did not describe a securing structure as being specific for attaching to the back, as opposed to some other portion, of a portable media player or case. The PTAB further stated that the specification indicates that the invention would be useful when attached to the media player generally, but does not specify attachment to the back as a requirement.

Thus, the PTAB concluded that Grinfas discloses a securing element inherently capable of being attached to the back of a portable media player, and that Grinfas discloses the securing element limitation of claim 9. The PTAB also found that Grinfas discloses all other limitations of claim 9 and that Grinfas anticipates all of the disputed claims.

Comments

The opinion pointed out that there is a risk in choosing to define an element functionally in an apparatus claim. A functional claim limitation in an apparatus claim may be considered as an intended use, and the prior art will satisfy the limitation if it is reasonably capable of performing the function.

The ‘031 patent also included a method claim (claim 16). The method claim recited attaching the socket to a portable media player; selectively extending the socket; and selectively retracting the socket. However, the method claim did not recite attaching the socket to the “back” of the portable media player.

It appears from the PTAB decision that the patent owner may have had a chance to avoid anticipation if they could actually show that the function “recites a fundamental characteristic without which the invention would be of little use.” The decision appears to give weight to the patent owner’s argument that if the function “recites a fundamental characteristic without which the invention would be of little use,” then the prior art must actually disclose performing the function.

Definitely Consisting Essentially Of: Basic and Novel Properties Must Be Definite Under 35 U.S.C. §112

| November 15, 2019

HZNP Medicines, LLC, Horizon Pharma USA, Inc. v. Actavis Laboratories UT, Inc.

October 15, 2019

Before: Prost, Reyna and Newman; Opinion by: Reyna; Dissent-in-part by: Newman

Summary: Horizon appealed a claim construction that the term “consisting essentially of” was indefinite. The district court evaluated the basic and novel properties under the Nautilus definiteness standard and found that the properties set forth in Horizon’s specification where indefinite. Horizon maintained this was legal error. The CAFC found that having used the phrase “consisting essentially of,” Horizon thereby incorporated unlisted ingredients or steps that do not materially affect the basic and novel properties of the invention. They asserted that a drafter cannot later escape the definiteness requirement by arguing that the basic and novel properties of the invention are in the specification, not the claims. Newman dissents, noting that no precedent has held that “consisting essentially of” composition claims are invalid unless they include the properties of the composition in the claims and that the majority’s ruling “sows conflict and confusion.”

Details:

- Background

HZNP Medicines, LLC, Horizon Pharma USA, Inc (“Horizon”) owns a series of patents directed to a methods and compositions for treating osteoarthritis. Actavis Laboratories UT, Inc (“Actavis”) sought to manufacture a generic version. Horizon sued Actavis for infringement in the District of New Jersey. Most of Horizon’s claims were removed by Summary Judgment on multiple issues. One claim survived to trial and was found valid and infringed. The CAFC taking up the appeal and cross-appeal on a number of issues (induced infringement, obviousness of a modified chemical formula and indefiniteness) affirmed the District Court.

This paper focuses on the ruling that Horizon claims using the “consisting essentially of” transitional phrase where invalid based on the basic and novel properties being indefinite under 35 U.S.C. §112.

- The CAFC’s Decision

Several of the claims in the Horizon patents recited a formulation “consisting essentially of” various ingredients. Claim 49 of the ’838 patent was used as the example.

49. A topical formulation consisting essentially of:

1–2% w/w diclofenac sodium;

40–50% w/w DMSO;

23–29% w/w ethanol;

10–12% w/w propylene glycol;

hydroxypropyl cellulose; and

water to make 100% w/w, wherein the topical formulation has a viscosity of 500–5000 centipoise.

The claims had been found invalid by the District Court under Summary Judgement following a Markman hearing. The parties’ dispute focused on the basic and novel properties of the claims. The CAFC agreed with the District Court that these properties are implicated by virtue of the phrase “consisting essentially of,” which allows unlisted ingredients to be added to the formulation so long as they do not materially affect the basic and novel properties.

The district court held that the specification of the patents identified five basic and novel properties: (1) better drying time; (2) higher viscosity; (3) increased transdermal flux; (4) greater pharmacokinetic absorption; and (5) favorable stability. Further, the district court reviewed the characteristics and found that at least “better drying time” was indefinite because the specifications provided two separate manners of determining drying time which were inconsistent. Based thereon, they concluded that the basic and novel properties of the claimed invention were indefinite under Nautilus.

The CAFC evaluated whether the Nautilus definiteness standard applies to the basic and novel properties of an invention. Horizon had argued that the Nautilus definiteness standard focuses on the claims and therefore does not apply to the basic and novel properties of the invention. The majority found this argument to be “misguided” and asserted that by using the phrase “consisting essentially of” in the claims, the inventor in this case incorporated into the scope of the claims an evaluation of the basic and novel properties.

The use of “consisting essentially of” implicates not only the items listed after the phrase, but also those steps (in a process claim) or ingredients (in a composition claim) that do not materially affect the basic and novel properties of the invention. Having used the phrase “consisting essentially of,” and thereby incorporated unlisted ingredients or steps that do not materially affect the basic and novel properties of the invention, a drafter cannot later escape the definiteness requirement by arguing that the basic and novel properties of the invention are in the specification, not the claims.

They supported this position by noting that a patentee can reap the benefit of claiming unnamed ingredients and steps by employing the phrase “consisting essentially of” so long as the basic and novel properties of the invention are definite.

In evaluating the district courts finding of indefiniteness, the CAFC maintained that two questions arise when claims use the phrase “consisting essentially of.” The first focusing on definiteness: “what are the basic and novel properties of the invention?” The second, focusing on infringement: “does a particular unlisted ingredient materially affect those basic and novel properties?” The definiteness inquiry focuses on whether a person of ordinary skill in the art (“POSITA”) is reasonably certain about the scope of the invention. If the POSITA cannot as-certain the bounds of the basic and novel properties of the invention, then there is no basis upon which to ground the analysis of whether an unlisted ingredient has a material effect on the basic and novel properties. Keeping with this logic, the CAFC maintained that to determine if an unlisted ingredient materially alters the basic and novel properties of an invention, the Nautilus definiteness standard requires that the basic and novel properties be known and definite.

Hence, the CAFC concluded that the district court did not err in considering the definiteness of the basic and novel properties during claim construction.

The majority then looked to the specific finding of indefiniteness by the district court regarding the basic and novel property of “better drying time.” They noted that the specification discloses results from two tests: an in vivo test and an in vitro test. The district court had found that the two different methods for evaluating “better drying time” do not provide consistent results at consistent times. Accordingly, CAFC affirmed the district court’s conclusion that the basic and novel property of “better drying rate” was indefinite, and consequently, that the term “consisting essentially of” was likewise indefinite.

In sum, we hold that the district court did not err in: (a) defining the basic and novel properties of the formulation patents; (b) applying the Nautilus definiteness standard to the basic and novel properties of the formulation patents; and (c) concluding that the phrase “consisting essentially of” was indefinite based on its finding that the basic and novel property of “better drying time” was indefinite on this record.

However, they noted that the Nautilus standard was not to be applied in an overly stringent manner.

To be clear, we do not hold today that so long as there is any ambiguity in the patent’s description of the basic and novel properties of its invention, no matter how marginal, the phrase “consisting essentially of” would be considered indefinite. Nor are we requiring that the patent owner draft claims to an untenable level of specificity. We conclude only that, on these particular facts, the district court did not err in determining that the phrase “consisting essentially of” was indefinite in light of the indefinite scope of the invention’s basic and novel property of a “better drying time.”

Judge Newman’s Dissent

Judge Newman dissented. She asserted that the majority holding that “By using the phrase ‘consisting essentially of’ in the claims, the inventor in this case incorporated into the scope of the claims an evaluation of the basic and novel properties” is not correct as a matter of claim construction, it is not the law of patenting novel compositions, and it is not the correct application of section 112(b).

First, she noted that there is no precedent that when the properties of a composition are described in the specification, the usage “consisting essentially of” the ingredients of the composition invalidates the claims when the properties are not repeated in the claims.

Second, in regard to the specifics of “drying time” for the case at hand, she noted that whatever the significance of drying time as an advantage of the claimed composition, recitation and measurement of this property in the specification does not convert the composition claims into invalidating indefiniteness because the ingredients are listed in the claims as “consisting essentially of.”

The role of the claims is to state the subject matter for which patent rights are sought. The usage “consisting essentially of” states the essential ingredients of the claimed composition. There are no fuzzy concepts, no ambiguous usages in the listed ingredients. There is no issue in this case of the effect of other ingredients…

Noting that there was no evidence that a POSITA would not understand the components of the composition claims with reasonable certainty, Newman concluded that since in the current case there are no other components asserted to be present, no “unnamed ingredients and steps” that even adopting the construction taken by the majority the claims are not subject to invalidity for indefiniteness.

Takeaways:

Added caution must be taken by patent prosecutors when electing to use the transitional phrase “consisting essentially of”. The specification needs to be clear as to what the basic and novel properties are and how they are determinable.

When using “consisting essentially of” incorporating the properties that are considered to be basic and novel into the claim language may help prevent ambiguity.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. §112 > basic and novel properties > consisting essentially of > definiteness

Presenting multiple arguments in prosecution risks prosecution history estoppel on each of them

| November 8, 2019

Amgen Inc. v. Coherus BioSciences Inc.

July 29, 2019

Before Reyna, Hughes, and Stoll. Opinion by Stoll.

Summary

The CAFC affirmed a district court decision holding that Amgen had failed to state a claim and dismissed Amgen’s suit against Coherus for patent infringement under the doctrine of equivalents, in view of Amgen’s clear and unmistakable disclaimer of claim scope during prosecution.

Details

Amgen Inc. and Amgen Manufacturing Ltd. (“Amgen”) sued Coherus BioSciences Inc. for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,273,707 (the ‘707 patent). The patent relates to methods of purifying proteins using hydrophobic interaction chromatography (“HIC”), in which a buffered salt solution containing the desired protein is poured into a HIC column and the proteins are bound to a column matrix while the impurities are washed out. However, only a limited amount of protein can bind to the matrix. If too much protein is loaded on the column, some of the protein will be lost to the solution phase before elution.

Conventionally, a higher salt concentration in a buffer solution is provided to increase the dynamic capacity of the HIC column, but the higher salt concentration causes protein instability. Amgen’s ‘707 patent discloses a process that increases the dynamic capacity of a HIC column by providing combinations of salts instead of using a single salt.

According to the ‘707 patent, any one of the three combinations of salts – citrate and sulfate, citrate and acetate, or sulfate and acetate – allows for a decreased concentration of at least one of the salts to achieve a greater dynamic capacity without compromising the quality of the protein separation.

During prosecution, the Examiner rejected the claims as being obvious in view of U.S. Patent No. 5,231,178 (“Holtz”). In reply to the Examiner’s rejection, Amgen argued that:

(1) The pending claims recite a particular combination of salts. No combinations of salts are taught nor suggested in Holtz;

(2) No particular combinations of salts recited in the pending claims are taught or suggested in Holtz; and

(3) Holtz does not teach dynamic capacity at all.

Amgen also attached a declaration from the inventor. The declaration stated that the use of the three salt combinations leads to substantial increases in the dynamic capacity of a HIC column and “[use] of this particular combination of salts greatly improves the cost-effectiveness of commercial manufacturing by reducing the number of cycles required for each harvest and reducing the processing time for each harvest.”

The Examiner again rejected Amgen’s argument and took the position that the prior art does disclose salts used in a method of purification and that adjustment of conditions was within the skill of an ordinary artisan. This time, in response to the Examiner’s position, Amgen replied that Holtz does not disclose any combination of salts and does not mention the dynamic capacity of a HIC column. In particular, Amgen stated that it was a “lengthy development path” when choosing a working salt combination and that merely adding a second salt would not have been expected to result in the invention. The Examiner allowed the claims.

In 2016, Coherus sought FDA approval to market a biosimilar version of Amgen’s pegfilgrastim product. In 2017, Amgen sued Coherus for infringing the ‘707 patent under the doctrine of equivalents because Coherus’s process did not match any of the three explicitly recited salt combinations in the ‘707 patent. Coherus moved to dismiss Amgen’s complaint for failure to state a claim.

The district court agreed to dismiss the complaint. The district court noted that during prosecution, Amgen had distinguished Holtz by repeatedly arguing that Holtz did not disclose “one of the particular, recited combinations of salts” in the two responses and in the declaration. The district court held that “[t]he prosecution history, namely, the patentee’s correspondence in response to two office actions and a final rejection, shows a clear and unmistakable surrender of claim scope by the patentee.” In addition, the district court held that “by disclosing but not claiming the salt combination used by Coherus, Amgen had dedicated that particular combination to the public.”

Amgen appealed.

The CAFC affirmed the district Court’s dismissal and found that the “prosecution history estoppel has barred Amgen from succeeding on its infringement claim under the doctrine of equivalents.”

In the appeal, Amgen argued that it only had distinguished Holtz by stating that Holtz does not disclose increasing any dynamic capacity or mention any salt combination. Amgen also argued that the prosecution history should not apply here because the last response filed prior to allowance did not make the argument that Holtz failed to disclose the particular salt combinations.

Regarding Amgen’s first point – that during prosecution, only dynamic capacity had been used to distinguish Holtz – the CAFC noted the three grounds on which Amgen has relied for distinguishing Holtz, and the fact that Amgen had quoted the declaration in support of the particular combination of salts recited in the claims. The CAFC explained that “separate arguments create separate estoppels as long as the prior art was not distinguished based on the combination of these various grounds.”

The CAFC also disagreed with Amgen’s second point (that prosecution history estoppel should not apply because of their last response), commenting that “there is no requirement that argument-based estoppel apply only to arguments made in the most recent submission before allowance… We see nothing in Amgen’s final submission that disavows the clear and unmistakable surrender of unclaimed salt combinations made in Amgen’s response.”

The CAFC held that the prosecution history estoppel applied and affirmed the District Court’s order dismissing Amgen’s complaint for failure to state a claim. The CAFC did not discuss whether Amgen dedicated unclaimed salt combinations to the public.

Takeaway

- Prosecution history estoppel can be triggered, not only by narrowing amendments, but also by arguments, even without any amendments.

- Presenting multiple arguments does not eliminate the risk of triggering estoppel for each of them.

- When writing an argument, avoid using expressions that are not recited in the claims (when discussing the claimed invention) or the cited documents (when discussing the state of the art).

The CAFC’s Holding that Claims are Directed to a Natural Law of Vibration and, thus, Ineligible Highlights the Shaky Nature of 35 U.S.C. 101 Evaluations

| November 1, 2019

American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. v. Neapco Holdings, LLC

October 9, 2019

Opinion by: Dyke, Moore and Taranto (October 3, 2019).

Dissent by: Moore.

Summary:

American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. (AAM) sued Neapco Holdings, LLC (Neapco) for alleged infringement of U.S. Patent 7,774,911 for a method of manufacturing driveline propeller shafts for automotive vehicles. On appeal, the Federal Circuit upheld the District Court of Delaware’s holding of invalidity under 35 U.S.C. 101. The Federal Circuit explained that the claims of the patent were directed to the desired “result” to be achieved and not to the “means” for achieving the desired result, and, thus, held that the claims failed to recite a practical way of applying underlying natural law (e.g., Hooke’s law related to vibration and damping), but were instead drafted in a results-oriented manner that improperly amounted to encompassing the natural law.

Details:

- Background

The case relates to U.S. Patent 7,774,911 of American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. (AAM) which relates to a method for manufacturing driveline propeller shafts (“propshafts”) with liners that are designed to attenuate vibrations transmitted through a shaft assembly. Propshafts are employed in automotive vehicles to transmit rotary power in a driveline. During use, propshafts are subject to excitation or vibration sources that can cause them to vibrate in three modes: bending mode, torsion mode, and shell mode.

The CAFC focused on independent claims 1 and 22 as being “representative” claims, noting that AAM “did not argue before the district court that the dependent claims change the outcome of the eligibility analysis.”

| Claim 1 | Claim 22 |

| 1. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising: providing a hollow shaft member; tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member; and positioning the at least one liner within the shaft member such that the at least one liner is configured to damp shell mode vibrations in the shaft member by an amount that is greater than or equal to about 2%, and the at least one liner is also configured to damp bending mode vibrations in the shaft member, the at least one liner being tuned to within about ±20% of a bending mode natural frequency of the shaft assembly as installed in the driveline system. | 22. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising: providing a hollow shaft member; tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner, and inserting the at least one liner into the shaft member; wherein the at least one liner is a tuned resistive absorber for attenuating shell mode vibrations and wherein the at least one liner is a tuned reactive absorber for attenuating bending mode vibrations. |

As explained by the CAFC, “[i]t was known in the prior art to alter the mass and stiffness of liners to alter their frequencies to produce dampening,” and “[a]ccording to the ’911 patent’s specification, prior art liners, weights, and dampers that were designed to individually attenuate each of the three propshaft vibration modes — bending, shell, and torsion — already existed.” The court further explained that in the ‘911 patent “these prior art damping methods were assertedly not suitable for attenuating two vibration modes simultaneously,” i.e., “shell mode vibration [and] bending mode vibration,” but “[n]either the claims nor the specification [of the ‘911 patent] describes how to achieve such tuning.”

The District Court concluded that the claims were directed to laws of nature: Hooke’s law and friction damping. And, the District Court held that the claims were ineligible under 35 U.S.C. 101. AAM appealed.

- The CAFC’s Decision

Under 35 U.S.C. 101, “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof” may be eligible to obtain a patent, with the exception long recognized by the Supreme Court that “laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable.”

Under the Supreme Court’s Mayo and Alice test, a 101 analysis follows a two-step process. First, the court asks whether the claims are directed to a law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea. Second, if the claims are so directed, the court asks whether the claims embody some “inventive concept” – i.e., “whether the claims contain an element or combination of elements that is sufficient to ensure that the patent in practice amounts to significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself.”

At step-one, the CAFC explained that to determine what the claims are directed to, the court focuses on the “claimed advance.” In that regard, the CAFC noted that the ‘911 patent discloses a method of manufacturing a driveline propshaft containing a liner designed such that its frequencies attenuate two modes of vibration simultaneously. The CAFC also noted that AAM “agrees that the selection of frequencies for the liners to damp the vibrations of the propshaft at least in part involves an application of Hooke’s law, which is a natural law that mathematically relates mass and/or stiffness of an object to the frequency that it vibrates. However, the CAFC also noted that “[a]t the same time, the patent claims do not describe a specific method for applying Hooke’s law in this context.”

The CAFC also noted that “even the patent specification recites only a nonexclusive list of variables that can be altered to change the frequencies,” but the CAFC emphasized that “the claims do not instruct how the variables would need to be changed to produce the multiple frequencies required to achieve a dual-damping result, or to tune a liner to dampen bending mode vibrations.”

The CAFC explained that “the claims general instruction to tune a liner amounts to no more than a directive to use one’s knowledge of Hooke’s law, and possibly other natural laws, to engage in an ad hoc trial-and-error process … until a desired result is achieved.”

The CAFC explained that the “distinction between results and means is fundamental to the step 1 eligibility analysis, including law-of-nature cases.” The court emphasized that “claims failed to recite a practical way of applying an underlying idea and instead were drafted in such a results-oriented way that they amounted to encompassing the [natural law] no matter how implemented.

At step-two, the CAFC stated that “nothing in the claims qualifies as an ‘inventive concept’ to transform the claims into patent eligible matter.” The CAFC explained that “this direction to engage in a conventional, unbounded trial-and-error process does not make a patent eligible invention, even if the desired result … would be new and unconventional.” As the claims “describe a desired result but do not instruct how the liner is tuned to accomplish that result,” the CAFC affirmed that the claims are not eligible under step two.

NOTE: In response to Judge Moore’s dissent, the CAFC explained that the dissent “suggests that the failure of the claims to designate how to achieve the desired result is exclusively an issue of enablement.” However, the CAFC expressed that “section 101 serves a different function than enablement” and asserted that “to shift the patent-eligibility inquiry entirely to later statutory sections risks creating greater legal uncertainty, while assuming that those sections can do work that they are not equipped to do.”

- Judge Moore’s Dissent

Judge Moore strongly dissented against the majority’s opinion. Judge Moore argued, for example, that:

- “The majority’s decision expands § 101 well beyond its statutory gate-keeping function and the role of this appellate court well beyond its authority.”

- “The majority’s concern with the claims at issue has nothing to do with a natural law and its preemption and everything to do with concern that the claims are not enabled. Respectfully, there is a clear and explicit statutory section for enablement, § 112. We cannot convert § 101 into a panacea for every concern we have over an invention’s patentability.”

- “Section 101 is monstrous enough, it cannot be that now you need not even identify the precise natural law which the claims are purportedly directed to.” “The majority holds that they are directed to some unarticulated number of possible natural laws apparently smushed together and thus ineligible under § 101.”

- “The majority’s validity goulash is troubling and inconsistent with the patent statute and precedent. The majority worries about result-oriented claiming; I am worried about result-oriented judicial action.”

Takeaways:

- When drafting claims, be mindful to avoid drafting a “result-oriented” claim that merely recites a desired “result” of a natural law or natural phenomenon without including specific steps or details setting establishing “how” the results are achieved.

- When drafting claims, be mindful that although under 35 U.S.C. 112 supportive details satisfying enablement are only required to be within the written specification, under 35 U.S.C. 101 supportive details satisfying eligibility must be within the claims themselves.