No likelihood of confusion with the mark BLUE INDUSTRY and opposer’s numerous marks having INDUSTRY as an element

| June 25, 2021

Pure & Simple Concepts, Inc. v. I H W Management Limited, DBA Finchley Group (non-precedential)

Decided on May 24, 2021

Moore, Reyna, Chen (opinion by Reyna)

Summary

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“the CAFC”) affirmed the Board’s determination of no likelihood of confusion or dilution between numerous marks of Pure & Simple Concepts, Inc. (hereinafter “P&S”) having the shared term “INDUSTRY” and “BLUE INDUSTRY” mark of I H W Management Limited, d/b/a The Finchley Group (hereinafter “Fincley”).

Details

P&S owns eight registered trademarks which all use the word “INDUSTRY” and licenses the use of these marks in connection with apparel items. On April 30, 2015, Finchley filed an application to register the mark BLUE INDUSTRY for various clothing items. P&S opposed registration of Finchley’s mark under Section 2(d) and 43(c) of the Lanham Act on the grounds of likelihood of confusion and likelihood of dilution by blurring based on P&S’s previous use and registration of its numerous INDUSTRY marks. The Board dismissed the opposition, finding that P&S failed to prove a likelihood of confusion, and that P&S failed to establish the critical element of fame for dilution.

P&S appealed to the CAFC, contending that the Board erred by (1) not considering all relevant DuPont factors; (2) determining the word “BLUE” to be the dominant term in Finchley’s mark; (3) relying heavily on third-party registrations; and (4) failing to find P&S’s family of marks as being famous.

First, in arguing that the Board erred by not considering all relevant DuPont factors, P&S contended that the Board did not consider that clothing items are more likely to be purchased on an impulse, and therefore, consumers are more likely to be confused. Finchley argued that this argument concerns the DuPont factor 4, which P&S presented no evidence before the Board. The CAFC agreed with Finchley, finding that P&S failed to present the evidence, and accordingly, P&S forfeited argument as to this factor.

Next, P&S contended that the Board erred in concluding that “BLUE” is the dominant term in the commercial impression created by Finchley’s mark. While it is not proper to dissect a mark, “one feature of a mark may be more significant than other features, and [thus] it is proper to give greater force and effect to that dominant feature.” Giant Food, Inc. v. Nation’s Foodservice, Inc., 710 F.2d 1565, 1570 (Fed. Cir. 1983). P&S cited as an example, Trump v. Caesars World, Inc., 645 F. Supp. 1015, 1019 (D.N.J. 1986), where the second word, “Palace,” was found to be dominant in the marks TRUMP PALACE and CEASER’S PALACE. However, the CAFC determined that the Board’s finding that BLUE to be the lead term in Finchley’s mark, and that the term BLUE is most likely to be impressed upon the minds of the purchasers and be remembered was supported by substantial evidence.

Third, P&S argued that the Board erred by heavily relying on third-party registrations. P&S argued that some of these third-party registrations were listed twice, some were canceled, some had no evidence of use, and some listed different goods. Nevertheless, the CAFC affirmed that the term “INDUSTRY,” or the plural thereof, has been registered by numerous third parties to identify clothing and apparel items, and therefore, the term is weak, and the scope is limited as applied to clothing items.

Finally, as to P&S’s dilution claim, the Board determined that the number of registered marks by third parties having the INDUSTRY element precluded a finding that P&S owns a family of marks for the shared INDUSTRY element. In addition, the evidence presented by P&S was insufficient to prove that the marks were famous. The CAFC agreed with the Board’s finding of P&S’s dilution claim.

The CAFC found the Board’s findings are supported by substantial evidence, and the Board correctly found there was no likelihood of confusion of dilution.

Takeaway

- Certain portions of a mark can be determined as being dominant.

- Third party registrations are relevant in proving weakness of certain portions of a mark.

Tags: Dilution > Likelihood of Confusion under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d) > Trademark

Trademark licensing agreements are not distinguishable from other types of contracts – the contracting parties are generally held to the terms for which they bargained

| March 23, 2021

Authentic Apparel Group, LLC, et al. v. United States

March 4, 2021

Lourie, Dyk, Stoll (opinion by Lourie)

Summary

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“the CAFC”) upheld the grant of summary judgement by United States Court of Federal Claims (“the Claims Court”), finding the plaintiff’s arguments unpersuasive. The CAFC found trademark licensing agreement to not be any different from other types of contracts, and there was no legal or factual reason to deviate from a plain reading of the exculpatory clauses in the trademark license agreement between the plaintiff and the defendant.

Details

Department of the Army (“Army”) and Authentic Apparel Group, LLC (“Authentic”) entered into a nonexclusive license for Authentic to manufacture and sell clothing bearing the Army’s trademarks in exchange for royalties. The license agreement stated that prior to any sale or distribution, Authentic must submit to the Army all products and marketing materials bearing the Army’s trademark for the Army’s written approval. The license also included exculpatory clauses that exempted the Army from liability for exercising its discretion to deny approval.

Between 2011 and 2014, Authentic submitted nearly 500 requests for approval to the Army, of which 41 were denied. During this time period, several formal notices were sent to Authentic, stating Authentic’s failures to timely submit royalty reports and pay royalties. Authentic eventually paid royalties through 2013, but on November 24, 2014, but expressed its intention of not paying outstanding royalties for 2014, and that it would sue the government for damages.

On January 6, 2015, Authentic and Ruben filed a complaint in the Claims Court for breach of contract. The allegations of breach were based on “the Army’s denial of the right to exploit the goodwill associated with the Army’s trademarks, refusal to permit Authentic to advertise its contribution to certain Army recreation programs, delay of approval for a financing agreement for a footwear line, and denial of approval for advertising featuring the actor Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson.” The Claims Court dismissed Ruben as a plaintiff for lack of standing. Authentic subsequently amended its complaint to include an allegation that “the Army breached the implied duty of good faith and fair dealings by not approving the sale of certain garments.”

One November 27, 2019, the Claims Court granted the government’s motion for summary judgment, determining that Authentic could not recover damages based on the Army’s exercise of discretion in view of the express exculpatory clauses included in the license agreement. With regard to Authentic’s amended complaint, the Claims Court also found that the Army’s conduct was not unreasonable, and in line with its obligation under the agreement.

The plaintiffs appealed, challenging dismissal of Ruben as a plaintiff, and the Claims Court’s grant of summary judgment.

With regard to the dismissal of Ruben as a plaintiff, the CAFC ruled that the Claims Court properly dismissed Ruben for lack of standing, as he was not a party to the license agreement, and there is no indication of Ruben as an intended beneficiary of the agreement.

The CAFC then turned to the Claims Court’s grant of summary judgment. The CAFC stated that the license agreement expressly stated that the Army had “sole and absolute discretion” regarding approval of Authentic’s proposed products and marketing materials.

Authentic argued that even if the Army has broad approval discretion under the agreement, that discretion cannot be so broad as to allow the Army to refuse to permit the use of its trademarks “for trademark purposes.” However, the CAFC ruled that the Army’s conduct was not at odd with principles of trademark law. Authentic’s argument appeared to distinguish trademark licenses from other types of contracts, but the CAFC stated that underlying subject matter of the contract is not an issue, and contracting parties are “generally held to the terms of which they bargained.”

The CAFC found Authentic’s argument to be problematic also in that it relies on an outdated model of trademark licensing law, where, at one point, “a trademark’s sole purpose was to identify for consumers the products’ physical source of origin,” and therefore, trademark licensing was “philosophically impossible.” Under the current law, trademark licenses are allowed as long as the trademark owner exercises quality control over the products associated with its trademarks. Here, Army fulfilled its duty of quality control with an approval process.

The CAFC considered Authentic’s arguments and found them unpersuasive, thus affirming the Claims Court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of the government.

Takeaway

- Review carefully the terms of any licensing agreement and negotiate for terms prior to signing. Trademark license agreements are not any different from other types of contracts, and the parties are generally held to the terms of the contracts.

“Kitchen” Sinks QuikTrip’s Trademark Opposition: The Federal Circuit Explains that Although Trademarks are Evaluated in their Entireties, when Determining Similarities between Trademarks, More Weight Is Applied to Distinctive Aspects of the Trademarks

| January 20, 2021

Quiktrip West, Inc. v. Weigel Stores, Inc

January 7, 2021

Lourie, O’Malley, and Reyna, (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

QuikTrip filed a trademark opposition in the U.S. Patent & Trademarks Office (U.S.P.T.O.) against Weigel in relation to Weigel’s application for the trademark W Kitchens based on QuikTrip’s assertion that Weigel’s trademark is likely to cause confusion in relation to Quiktrip’s registered trademark QT Kitchen. The Board at the U.S.P.T.O. found that the dissimilarity of the marks weighed against the likelihood of confusion and dismissed QuikTrip’s opposition. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s decision. The Federal Circuit explained that the Board correctly evaluated the trademarks in their entireties, while properly giving lower weight to less distinctive aspects of the trademark, such as the term “kitchen.” The Federal Circuit also noted that although some evidence suggested that Weigel may have copied QuikTrip’s trademark, the fact that Weigel modified its trademark multiple times in response to QuikTrip’s allegations of infringement negated any inference of an intent to deceive or cause confusion.

Background

- The Factual Setting

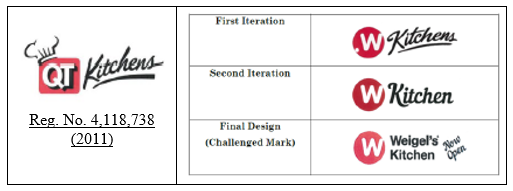

QuikTrip operates a combination gasoline and convenience store, and has sold food and beverages under its registered mark QT Kitchens (shown below left) since 2011.

In 2014, Weigel started using the stylized mark W Kitchens shown at the top-right below (First Iteration). QuikTrip sent Weigel a cease-and-desist letter. In response, Weigel adapted its mark to change Kitchens to Kitchen and to adapt the stylizing as shown at the middle-right below (Second Iteration). In response, QuikTrip demanded further modification by Weigel, and Weigel again adapted its mark to further change the font, to add its’ name Weigel’s and to include “new open” as shown at the bottom-right below (Final Challenged Mark).

The U.S.P.T.O. Proceedings

Weigel applied to register its’ Final Challenged Mark with the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (application no. 87/324,199), and QuikTrip filed an opposition to Weigel’s mark under 15 U.S.C. 1052(d) asserting that it would create a likelihood of confusion with its QT Kitchens mark.

The Board evaluated the likelihood of confusion and found that the dissimilarity of the marks weighed against the likelihood of confusion and dismissed QuikTrip’s opposition to Weigel’s registration of its mark.

QuikTrip appealed the Board’s decision to the Federal Circuit.

The Federal Circuit’s Decision

The Federal Circuit reviews the Board’s legal determination de novo, but reviews the underlying findings of fact based on substantial evidence.

Here, the legal analysis involves the determination of whether the mark being sought is “likely, when used on or in connection with the goods of the applicant, to cause confusion” with another registered mark. See 15 U.S.C. 1052(d) of the Lanham Act. The likelihood of confusion evaluation is a legal determination based on underlying findings of fact relating to the longstanding factors set forth in E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 476 F. 2d 1357 (C.C.P.A. 1973). For reference, these factors include:

- The similarity of the marks (e.g., as viewed in their entireties as to their appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression);

2. The similarity and nature of the goods and services;

3. The similarity of the established trade channels;

4. The conditions under which, and buyers to whom, sales are made (e.g., impulse

verses sophisticated purchasing);

5. The fame of the prior mark;

6. The number and nature of similar marks in use on similar goods (e.g., by 3rd

parties);

7. The nature and extent of any actual confusion;

8. The length of time during, and the conditions under which, there has been

concurrent use without evidence of actual confusion;

9. The variety of goods on which a mark is or is not used;

10. The market interface between the applicant and the owner of a prior mark;

11. The extent to which applicant has a right to exclude others from use of its mark;

12. The extent of possible confusion;

13. Any other established fact probative of the effect of use.

On Appeal, QuikTrip challenges the Board’s analysis regarding the Dupont factor number one (1) based on “similarity of the marks” and the Dupont factor thirteen (13) based on “other established fact probative of the effect of use” which other fact is asserted by QuikTrip as being the “bad faith” of Weigel.

- Factor 1 (Similarity of the Marks)

With respect to the first factor pertaining to the similarity of the marks, QuikTrip asserted that the Board incorrectly “dissected the marks when analyzing their similarity” rather than rendering its determination based on the similarity of “the marks in their entireties.”

First, QuikTrip argued that the Board improperly “ignored the substantial similarity created by … the shared word Kitchen(s)” and gave “undue weigh to other dissimilar portions of the marks.” In response, the Federal Circuit explained that “[i]t is not improper for the Board to determine that ‘for rational reasons’ it should give ‘more or less weight’ to a particular feature of the mark” as long as “its ultimate conclusion … rests on a consideration of the marks in their entireties.”

Here, the Federal Circuit indicated that the portion “Kitchen(s)” should “accord less weight” because “kitchen” is a “highly suggestive, if not descriptive, word” and also because there were numerous “third-party uses, and third-party registrations of marks incorporating the word “kitchen” for sale of food and food-related services.”

Moreover, the Federal Circuit explained that “the Board was entitled to afford more weight to the dominant, distinct portions of the marks” which included “Weigel’s encircled W next to the surname Weigel’s and QuikTrip’s QT in a square below a chef’s hat” emphasizing “given their prominent placement, unique design and color.”

The Federal Circuit also noted that the Board compared the marks in their entireties and further observe that: 1) the marks contained different letters and geometric shapes; 2) QuikTrip’s mark included a tilted chef’s hat; 3) phonetically, the marks do “not sound similar,” and the component Weigel’s adds an entirely different sound; and 4) the commercial impressions and connotations are different.

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit expressed that the Board’s finding of a lack of similarity was supported by substantial evidence.

- Factor 13 (Bad Faith as Another Probative Factor)

With respect to the thirteenth factor pertaining to asserted “bad faith” as being another probative factor, QuikTrip asserted that the evidence showed that Weigel acted in bad faith and that such bad faith further supported a finding of a likelihood of confusion.

However, the Federal Circuit explained that “an inference of ‘bad faith’ requires something more than mere knowledge of a prior similar mark.” Moreover, the Federal Circuit further explained that “[t[he only relevant intent is [an] intent to confuse.” The Federal Circuit noted that “[t]here is a considerable difference between an intent to copy and an intent to deceive.”

Accordingly, although the evidence showed that Weigel had taken photographs of QuikTrip’s stores and examined QuikTrip’s marketing materials, the Federal Circuit expressed that there was not an intent to deceive. In particular, the Federal Circuit emphasized that Weigel’s “willingness to alter its mark several times in order to prevent customer confusion [in response to QuikTrip’s cease-and-desist demands] negates any inference of bad faith.”

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the decision of the Board.

Takeaways

- In evaluating similarities between trademarks for the determination of potential likelihood of confusion, although the evaluation is based on the marks in their entireties, different portions of the marks may be afforded different weight depending on circumstances. Accordingly, it is important to identify portions of the mark that are more distinctive in contrast to portions of the mark that may be descriptive or suggestive or commonly used in other marks.

- Although “bad faith” can help support a conclusion of a likelihood of confusion, it is important to keep in mind that “bad faith” does not merely require an “intent to copy,” but requires an “intent to deceive.”

- In the event that a trademark owner demands an alleged infringer cease-and-desist use of a mark, if the accused infringer substantially modifies its trademark in an effort to prevent customer confusion, according to the Federal Circuit, such action would “negate any inference of bad faith.” Accordingly, in order to help avoid any inference of bad faith, in response to a cease-and-desist demand, an accused infringer can help to avoid such an inference by modifying its trademark.

Tags: “DuPont Factors” Test > Likelihood of Confusion under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d) > Similarity of Marks > Trademark

Box designs for dispensing wires and cables affirmed as functional, not registrable as trade dresses

| December 23, 2020

In re: Reelex Packaging Solution, Inc. (nonprecedential)

November 5, 2020

Moore, O’Malley, Taranto (Opinion by O’Malley)

Summary

In a nonprecedential opinion, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”), affirmed the decision of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (the “TTAB”), upholding the examining attorney’s refusal to register two box designs for electric cables and wire as trade dresses on grounds that the designs are functional.

Details

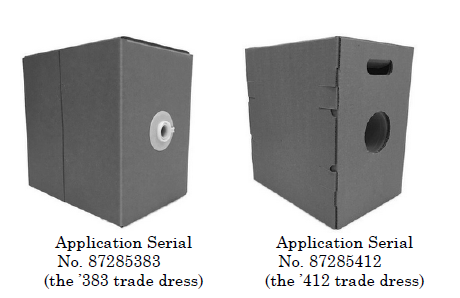

Reelex filed two trade dress applications for coils of cables and wire in International Class 9.

The trade dress of Application Serial No. 87285383 (the ‘383 trade dress) is described as follows:

The mark consists of trade dress for a coil of cable or wire, the trade dress comprising a box having six sides, four sides being rectangular and two sides being substantially square, the substantially square sides both having a length of between 12 and 14 inches, the rectangular sides each having a length of between 12 and 14 inches and a width of between 7.5 and 9 inches and a ratio of width to length of between 60% and 70%, one, and only one rectangular side having a circular hole of between 0.75 and 1.00 inches in the exact middle of the side with a tube extending through the hole and through which the coil is dispensed from the package, the tube having an outer end extending beyond an outer surface of the rectangular side, and a collar extending around the outer end of the tube on the outer surface of the rectangular side of the package, and one square side having a line folding assembly bisecting the square side.

The trade dress of Application Serial No. 87285412 (the ‘412 trade dress) is described as follows:

The mark consists of trade dress for a coil of cable or wire, the trade dress comprising a box having six sides, four sides being rectangular and two sides being substantially square, the substantially square sides both having a length of between 13 and 21 inches, the rectangular sides each having a length of the same length of the square sides and a width of between 57% and 72% of the size of the length, one, and only one rectangular side having a circular hole of 4.00 inches in the exact middle of the side with a tube extending in the hole and through which the coil is dispensed from the package, one square side having a tongue and a groove at an edge adjacent the rectangular side having the circular opening, and the rectangular side having the circular opening having a tongue and a groove with the tongue of each respective side extending into the groove of each respective side at a corner therebetween.

The examining attorney refused the applications, finding the design of the boxes as being functional and non-distinctive. Further, the examining attorney found that the designs do not function as trademarks to indicate the source of the goods. On an appeal to the TTAB, the Board affirmed the examining attorney to register on the grounds of functionality and distinctiveness. Regarding functionality, the Board found that the features of these boxes – the rectangular shape, built-in handle for the ‘412 design, and dimensions of the boxes and the size and placement of the payout tubes and payout holes, are “clearly dictated by utilitarian concerns.” The Board also found that the payout holes and their position on the boxes allowed users easy access and twist-free dispensing.

While the Board found above to be sufficient evidence to uphold the functionality refusal, the Board went further to considered the following four factors from In re Morton-Norwich Products, Inc., 671 F.2d 1332 (CCPA 1982):

(1) the existence of a utility patent that discloses the utilitarian advantages of the design sought to be registered;

(2) advertising by the applicant that touts the utilitarian advantages of the design;

(3) facts pertaining to the availability of alternative designs; and

(4) facts pertaining to whether the design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.

- Existence of a utility patent

With regard to the first factor, Reelex submitted five utility patents relating to the applied-for marks:

- U.S. Patent No. 5,810,272 for a Snap-On Tube and Locking Collar for Guiding Filamentary Material Through a Wall Panel of a Container Containing Wound Filamentary Material;

- U.S. Patent No. 6,086,012 for Combined Fiber Containers and Payout Tube and Plastic Payout Tubes;

- U.S. Patent No. 6,341,741 for Molded Fiber and Plastic Tubes;

- U.S. Patent No. 4,160,533 for a Container with Octagonal Insert and Corner Payout; and

- U.S. Patent No. 7,156,334 for a Pay-Out Tube.

The Board found that the patents revealed several benefits of various features of the two boxes, weighing in favor of finding the designs of the two boxes to be functional.

- Advertising by the applicant

The second factor also weighed in favor of finding functionality. Reelex’s advertising materials repeatedly touted the utilitarian advantages of the boxes, which allow for dispensing of cable or wire without kinking or tangling. The boxes’ recyclability, shipping, and storage advantages were also being touted. The evidence weighed in favor of finding functionality.

- Alternative designs

The Board explained that in cases where patents and advertising demonstrate functionality of designs, there is no need to consider the availability of alternative designs. Nevertheless, the Board considered evidence submitted by Reelex, and found the evidence to be speculative and contradictory to its own advertising and patents. Therefore, the Board found the evidence to be unpersuasive.

- Comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture

Regarding this last factor, the Board found no evidence of record regarding the cost or complexity of manufacturing the trade dress.

Considering and analyzing the case using the Morton-Norwich factors, the Board found the design of Reelex’s trade dress to be “essential to the use or purpose of the device” as used for “electric cable and wires.”

On appeal, Reelex argued that evidence shows that the trade dresses at issue “provide no real utilitarian advantage to the user.” In addition, Reelex argued that the Board erred in failing to consider evidence of alternative designs.

The CAFC found there to be substantial evidence to support the Board’s finding of multiple useful features in the design of the boxes, and these features were properly analyzed by the Board as a whole and in combination, and the Board did not improperly dissect the designs of the two trade dresses into discrete design features. The CAFC also found there to be sufficient evidence supporting the Board’s finding of functionality using the Morton-Norwich factors.

As to whether the Board considered Reelex’s evidence of alternative designs, the Board expressly considered Reelex’s evidence of alternative designs, and found the evidence to be both speculative and contradictory. For example, although the declaration submitted by Reelex stated that the shape of the package, as well as the shape, size, and location of the payout hole, were merely ornamental, Reelex’s utility patents repeatedly refer to the utilitarian advantages of the two box designs.

Therefore, the CAFC affirmed the decision of the Board, upholding the examining attorney’s refusal to register the two trade dress applications because they are functional.

Takeaway

- Functional designs cannot be registered as a trade dress. If a utility patent exists for a design, it is likely that the same design cannot also be protected as a trade dress.

- Note that there is an overlap in design patent and trade dress. Existence of a design patent does not preclude an applicant from filing a trademark application for the same design.

Proprietary interest is not required in seeking cancellation of a trademark registration

| August 31, 2020

Australian Therapeutic Supplies Pty. Ltd. v. Naked TM, LLC

July 27, 2020

O’Malley, Reyna, Wallach (Opinion by Reyna; Dissent by Wallach)

Summary

The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (the “TTAB”) determined that Australian Therapeutic Supplies Pty. Ltd. (“Australian”) lacked standing to bring a cancellation proceeding against a trademark registration of Naked TM, LLC (“Naked”), because Australian lacked proprietary rights in its unregistered marks. The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) reversed and remanded, holding that proprietary interest is not required in seeking cancellation of a trademark registration. By demonstrating real interest in the cancellation proceeding and a reasonable belief of damage, statutory requirement to bring a cancellation proceeding under 15 U.S.C. § 1064 is satisfied.

Details

Australian started using the mark NAKED and NAKED CONDOM for condoms in Australia in early 2000. Australian then began advertising, selling, and shipping the goods bearing the marks to customers in the United States starting as early as April 2003.

Naked owns U.S. Trademark Registration No. 3,325,577 for the mark NAKED for condoms. In 2005, Australian became aware of the trademark application filed on September 22, 2003 by Naked’s predecessor-in-interest. On July 26, 2006, Australian contacted Naked, claiming its rights in its unregistered mark. From July 26, 2006 to early 2007, Australian and Naked engaged in settlement negotiations over email. Naked asserts that the email communications resulted in a settlement, whereby Australian would discontinue use of its unregistered mark in the United States, and Australian consents to Naked’s use and registration of its NAKED mark in the United States. Australian asserts the parties failed to agree on the final terms of a settlement, and no agreement exists.

In 2006, Australian filed a petition to cancel registration of he NAKED mark, asserting Australian’s prior use of the mark, seeking cancellation on the grounds of fraud, likelihood of confusion, false suggestion of a connection, and lack of bona fide intent to use the mark. Naked responded, denying the allegations and asserting affirmative defenses, one of which was that Australian lacked standing, as Australian was contractually and equitably estopped from pursuing the cancellation.

Following trial, on December 21, 2018, the Board concluded that Australian lacked standing to bring the cancellation proceeding, reasoning that Australian failed to establish proprietary rights in its unregistered mark and therefore, lacked standing. The Board found that while no formal written agreement existed, through email communications and parties’ actions, the Board found that Australian led Naked to reasonably believe that Australian had abandoned its rights to the NAKED mark in the United States in connection with condoms. While the Board made no finding on whether Australian agreed not to challenge Naked’s use and registration of the NAKED mark, the Board concluded that Australian lacked standing because it could not establish real interest in the cancellation or a reasonably basis to believe it would suffer damage from Naked’s continued registration of the mark NAKED.

The statutory requirements to bring a cancellation proceeding under 15 U.S.C. § 1064 are 1) demonstration of a real interest in the proceeding; and 2) a reasonable belief of damage. The CAFC held that the Board erred by concluding that Australian lacked standing because it had no proprietary rights in its unregistered mark. Australian contracting away its rights to use the NAKED mark in the United States could bar Australian from proving actual damage, the CAFC clarified that 15 U.S.C. § 1064 requires only a belief of damage. In sum, establishing proprietary rights is not a requirement for demonstrating a real interest in the proceeding and a belief of damage.

Next, the CAFC considered whether Australian has a real interest and reasonable belief of damage such that is has a cause of action under 15 U.S.C. § 1064. Here, Australian demonstrates a real interest because it had twice attempted to register its mark in 2005 and 2012, but was refused registration based on a likelihood of confusion with Naked’s registered mark. The USPTO has suspended prosecution of Australian’s later-filed application, pending termination of the cancellation proceeding, which further demonstrates a belief of damage.

Naked argued that Australian’s applications do not support a cause of action because Australian abandoned its first application. It also argued that ownership of a pending application does not provide standing.

With regard to the first point, the CAFC stated that abandoning prosecution does not signify abandoning of its rights in a mark. As for the second point, Australian’s advertising and sales in the United States since April 2003, supported by substantial evidence, demonstrate a real interest and reasonable belief of damage.

While Naked questions the sufficiency of Australian’s commercial activity, the CAFC stated that minimum threshold of commercial activity is not imposed by 15 U.S.C. § 1064.

Therefore, the CAFC held that the Board erred by requiring proprietary rights in order to establish a cause of action under 15 U.S.C. § 1064. The CAFC also held that based on the facts before the Board, Australian had real interest and a reasonable belief of damage; the statutory requirements for seeking a cancellation proceeding is thereby satisfied. The CAFC reversed and remanded the case to the Board for further proceedings.

Dissenting Opinion

While Judge Wallach, in his dissenting opinion agreed that proprietary interest is not required, he disagreed with the majority’s finding that Australian met its burden of proving a real interest and a reasonable belief in damages. In this case, any “legitimate commercial interest” in the NAKED mark was contracted away, as was any “reasonable belief in damages”.

Takeaway

Proprietary interest is not required in seeking cancellation of a trademark registration. Statutory requirement to bring a cancellation proceeding under 15 U.S.C. § 1064 is satisfied by demonstrating real interest in the cancellation proceeding and a reasonable belief of damage.

Don’t raise issues for the first time before the CAFC unless it falls into one of the limited exceptions: the CAFC affirms the stylized letter “H” mark to be confusingly similar

| September 3, 2019

Hylete LLC v. Hybrid Athletics, LLC

August 1, 2019

Moore, Reyna, Wallach (Opinion by Reyna)

Summary

On appeal, Hylete LLC (“Hylete”) argued, for the first time, that the Board erred in its analysis by failing to compare its stylized “H” mark with “composite common law mark” of the Hybrid Athletics, LLC (“Hybrid”), comprising of the stylized letter “H” appearing above the phrase “Hybrid Athletics” and several dots underneath. By not presenting the argument during the opposition proceedings or at the request for reconsideration, the CAFC held that Hylete waived its argument, and upheld the decision of the Board.

Details

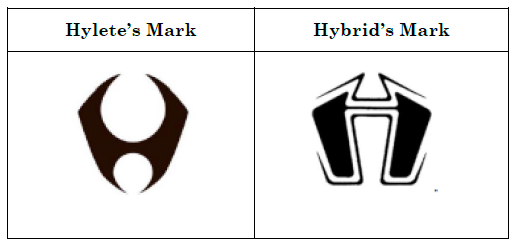

Hylete LLC applied to register a design mark for a stylized letter “H” in International Class 25 for “[a]thletic apparel, namely, shirts, pants, shorts, jackets, footwear, hats and caps.” Upon examination, the mark was approved for publication, and the mark published for opposition in the Trademark Official Gazette on June 18, 2013. After filing an extension of time to oppose, on October 16, 2013, Hybrid Athletics, LLC filed a Notice of Opposition on the grounds of likelihood of confusion with its mark under Section 2(d) of the Lanham Act. Hylete and Hybrid’s marks are as shown below:

Hybrid pleaded ownership in Application No. 86/000,809 for its design mark of a stylized “H” in connection with “conducting fitness classes; health club services, namely, providing instruction and equipment in the field of physical exercise; personal fitness training services and consultancy; physical fitness instruction” in International Class 41. Hybrid also pleaded common law rights arising from its use of the mark on “athletic apparel, including shirts, hats, shorts and socks” since August 1, 2008. The following images were submitted by Hybrid as evidence to show the use of the mark on athletic apparel:

All of the images showed the stylized “H” mark appearing above the phrase “Hybrid Athletics” and several dots underneath the phrase.

Hylete’s argument before the Board focused on the two stylized “H” designs having a different appearance, with each mark having its own distinct commercial impression. On December 15, 2016, the Board issued a final decision, sustaining Hybrid’s opposition, concluding that Hylete’s mark is likely to cause confusion with Hybrid’s mark. Hylete filed a request for reconsideration of the Board’s final decision, including an argument that “[t]here was no record evidence demonstrating that consumers would view [Hylete’s] mark as a stylized H” as a part of its commercial impression argument. The Board found that this argument is contrary to Hylete’s own characterization of the mark in its brief, as well as the testimony of its CEO, which admitted that both logos were Hs. The Board rejected Hylete’s argument and denied the request for rehearing. Hylete appealed the decision of the Board to the CAFC.

On appeal, Hylete argued that the Board erred in its analysis by failing to compare Hylete’s stylized “H” mark with Hybrid’s “composite common law mark,” comprising of the stylized letter “H” appearing above the phrase “Hybrid Athletics” and several dots underneath, as shown below:

In its appeal brief, Hylete stated as follows: “this appeal may be summarized into a single question: is Hylete’s mark sufficiently similar to [Hybrid’s] composite common law mark to be likely to cause confusion on the part of the ordinary consumer as to the source of the clothing items sold under those marks?”

In response, Hybrid stated that the “composite common law mark” arguments were never raised before the Board and are therefore waived.

The CAFC considers arguments made for the first time on appeal under the following limited circumstances:

- When new legislation is passed while an appeal is pending;

- When there is a change in the jurisprudence of the reviewing court or the Supreme Court after consideration of the case by the lower court;

- Even if the parties did not argue and the court below did not decide, when appellate court applies the correct law, if an issue is properly before the court; and

- Where a party appeared pro se.

Hylete did not dispute that the argument was not raised before the Board. Instead, Hylete contended that the argument has not been waived, because the Board “sua sponte” raised the issue of Hybrid’s common law rights in its final decision. The CAFC disagreed, stating that Hylete’s failure to raise the argument in the request for reconsideration negates its contention.

As Hylete could have raised the issue of Hybrid’s “composite common law mark” in the opposition proceedings or in the request for reconsideration, but did not do so, and as none of the exceptional circumstances in which the CAFC considers arguments made for the first time on appeals applies, the CAFC held that the issues raised by Hylete on appeal have been waived.

As the only issues Hylete raised on appeal concerned Hybrid’s “composite common law mark,” the CAFC affirmed the decision of the Board.

Takeaway

- Raise all possible arguments prior to appeal.

- It seems that the record before the Board lacked evidence that the letter H is conceptually weak or diluted in the context of the goods or in general – perhaps more evidence before the Board would have helped Hylete in this case. At the same time, perhaps presenting such evidence is not desirable to Hylete, as that would be an admission that its own mark is weak.

Absent information essential for customers to make a purchasing decision, a webpage specimen is not an acceptable display associated with the goods, but a mere advertisement

| May 10, 2019

In re: Siny Corp.

Nonprecedential Opinion Issued January 14, 2019

Precedential Opinion Issued April 10. 2019

Summary

The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board ruled, and the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed, a webpage specimen lacking information sufficient for a customer to make a decision to purchase was mere advertising material and not an acceptable specimen of use for goods. An indication of a phone number and email address under “For sales information” on a website showing the goods and the trademark used in close proximity was found insufficient for consumers to actually make a purchase, as it only shows how consumers could obtain more information necessary to make a purchase.

The CAFC had previously issued a nonprecedential opinion on January 14, 2019, but issued a precedential opinion on April 10, 2019 for this case pursuant to a request by the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

単なる宣伝資料は、商品の使用証明として不適切である。商品の近くに商標の表示されているウェブサイトにおいて、「販売情報」として電話番号とメールアドレスが掲載されていたとしても、それは、消費者が購入するために必要な情報を取得するための手段を示しているだけで、そのウェブサイトに掲載されている情報のみで消費者が実際に商品を購入することはできない。よって、そのようなウェブサイトは、商品についての単なる宣伝資料であり、使用証明にはならない。

Details

Siny Corp. filed an application for a trademark, seeking to register the standard character mark CASALANA for “Knit pile fabric made with wool for use as a textile in the manufacture of outerwear, gloves, apparel, and accessories.” To meet the requirements of a use in commerce application under Section 1(a) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1051(a), the applicant submitted a specimen of use for goods, a webpage showing the trademark used in close proximity to the photograph of the goods. The examining attorney refused registration, finding the specimen of use to be a mere advertising material, failing to show the required use in commerce for the goods. The applicant appealed to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board, and the Board affirmed in a split decision. The Board found that the specimen submitted by the applicant is submitted as a “display associated with the goods,” and for such a display to be found an acceptable specimen of use, it must be a “point of sale” display. The Board then found that the website submitted by the applicant lacked information sufficient for a customer to make a decision to purchase, such as “a price (or even a range of prices) for the goods, the minimum quantities one may order, accepted methods of payment, or how the goods would be shipped.” While the Board appreciated the applicant’s contention that the goods were “industrial materials for use by customers in manufacture,” and the sales transaction must involve the applicant’s sales personnel, the Board also found that “…if virtually all important aspects of the transaction must be determined from information extraneous to the web page, then the web page is not a point of sale.” The Board added that in cases where the goods are technical and specialized, and the applicant and examining attorney disagree on the point-of-sale nature of a submitted specimen, the applicant is advised to provide additional evidence and information regarding the manner in which purchases are made, such as providing verified statements from those knowledgeable about what happens and how.

The CAFC agreed with the Board. The CAFC disagreed with the applicant that the Board applied “overly rigid requirements” in reaching the determination that the specimen submitted by the applicant did not qualify as a display associated with the goods, and noted that the Board’s decision was made by carefully considering the contents of the submitted specimen.

Takeaway

- Catalogs and webpages that merely indicate contact information are usually not good specimens.

- If the goods are highly technical or specialized such that price/quantities/methods of payment/how goods will be shipped cannot be indicated on a display associated with the goods (i.e., website), consider submitting an affidavit.

- The USTPO has been reviewing specimens of use a lot more closely in recent years, and finding appropriate specimens of use for submission has become even more crucial.

“CHURRASCOS” determined generic for restaurant services – earlier registration have no bearing on the USPTO’s genericness analysis

| May 19, 2016

In re: Cordua Restaurants, Inc.

May 13, 2016

Before Prost, Dyk, Stoll. Opinion by Dyk.

Summary

Appellant Cordua Restaurants, Inc. (Cordua) applied to register a stylized word “CHURRASCOS” for “Bar and restaurant services; Catering.” Although Cordua had prior registration for the standard character mark “CHURRASCOS” for the same services, that the mark was registered in the Principal Register had no bearing on the USPTO’s determination of whether the stylized form of “CHURRASCOS” was generic. In addition, even if the public does not understand the term to refer to the broad genus of restaurant services as a whole, the term is still generic, as the relevant public understands the term to refer to a type of restaurant within the broad genus of restaurant services. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) affirmed the decision of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB), finding the mark to be generic, and ineligible for registration.

Cordua Restaurants, Inc.(以下、「Cordua社」)のCHURRASCOSデザイン文字商標出願は、CHURRASCOSという言葉が、レストランサービスについて使用された場合、一般用語であるため、登録はできないとして拒絶された。Cordua社は、先登録として、標準文字のCHURRASOCOS商標登録を有しており、この先登録が存在するため、デザイン文字出願の方も登録されるべきと主張したものの、CAFCはこれを受け付けなかった。また、CHURRASCOSという言葉が、レストランサービス全体において一般用語として認識されていない場合でも、当該者はその言葉を、レストランサービスという大きな括り中のレストランの一種類であると理解しているため、CHURRASCOSは一般用語である。

Designer’s Connection with Paris Insufficient to Overcome a Section 2(e)(3) Refusal

| October 24, 2012

In re Miracle Tuesday, LLC

October 4, 2012

Panel: Rader, Linn, O’Malley. Opinion by O’Malley

Summary

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed the decision of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“the Board”), refusing to register the mark JPK PARIS 75 and design on the grounds that it is primarily geographically deceptively misdescriptive under Section 2(e)(3) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(3). While the CAFC does not endorse a rule that the goods need to be manufactured in the named place to originate there, there must be some other direct connection between the goods and the place identified in the mark. In this case, the CAFC found there is no evidence of a current connection between the goods and Paris.

商標審判は、商標「JPK PARIS 75」は、「産地について誤信を生じさせる商標(primarily geographically deceptively misdescriptive)」であると認定し、CAFCは、これを支持した。 CAFCは、商品がその産地にて製造される必要があるとは示さなかったものの、商品とその産地には直接的な関係が必要であると示した。本件では、商品とパリに直接的な関係が存在するという証拠はなかった

Tags: geographical indication > geographically misdescriptive > Trademark

Using Trademark in Categories Other than the One as Filed May Result in Abandonment

| August 15, 2012

LENS.COM, INC. v. 1-800 CONTACTS, INC.

August 3, 2012

Panel: Newman, Linn and Moore. Opinion by Linn.

Summary

Lens.com, Inc. (“Lens.com”) appeals a decision of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) granting a motion for summary judgment by 1-800 Contacts, Inc. (“1-800 Contacts”) and ordering the cancellation of Lens.com’s registration for the mark LENS due to nonuse. The mark was filed to be used in connection with computer software, but the business of Lens.com is in the field of retail sales of contact lenses. The issue at dispute is whether software incidentally distributed in connection with retail business in the context of an internet service constitutes a “good in commerce.” The court applies a three-prong test established in non-internet-related case law to the current case in finding nonuse of the mark, and distinguishes the current case from an Eleventh Circuit decision.

Lens.com公司就商标裁决上诉委员会批准关于注销 LENS 商标登记的动议提出上诉。 该动议由1-800 Contacts公司提出,称lens.com已停止使用该商标。该商标注册为“计算机软件相关业务”的商标,而Lens.com仅在隐形眼镜零售领域开展业务。该案中的争议问题是互联网零售业务中偶尔附带发送的软件是否构成“商品”。法院利用了建立在非互联网相关案件的判例法上的“三因素测试”认定该商标已停止使用, 并且将本案与第十一巡回法庭判决的一个互联网相关案件加以对比区分。

Tags: abandonment > cancellation > Trademark > use in trade