Software Patents Demand Specific, Technologically Grounded Claims

| May 3, 2024

AI Visualize, Inc. vs. Nuance Communications, Inc. and Mach7 Technologies, Inc.

Decided: April 4, 2024

Before: MOORE, Chief Judge, REYNA, and HUGHES, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The Federal Circuit upheld a district court decision that dismissed AI Visualize’s patent infringement lawsuit against Nuance Communications and Mach7 Technologies. The court agreed with the lower court’s finding that the patents claimed patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101, focusing on abstract ideas without enough inventive concept to warrant patent protection.

Background

AI Visualize asserted that Nuance Communications and Mach7 Technologies had infringed on its patents related to the visualization of medical scans through a web-based portal. The patents at issue include four patents: U.S. Patent Nos. 8,701,167; 9,106,609; 9,438,667; and 10,930,397. All these patents share a common specification that describes systems and methods aimed at improving the access and visualization of volumetric medical data, such as that obtained from MRI and CT scans, through a web-based portal. The patented technology demonstrates a centralized system that processes medical scan data and visualizes it remotely, allowing efficient transmission of three-dimensional views over low-bandwidth connections, thus facilitating better diagnostic capabilities across diverse medical environments.

The central dispute revolved around whether the patented methods and systems constituted an abstract idea under the Alice two-step framework. Nuance and Mach7 argued that the patent claims failed to transform this abstract idea into a patent-eligible application due to lack of an inventive concept. The district court agreed, finding that the patents were directed to the basic concept of manipulating and displaying data, a task it considered routine and conventional in the field.

Claim 1 of the ‘609 patent, representing the first group of claims, was central to this dispute.

1. A system for viewing at a client device at a remote location a series of three-dimensional virtual views over the Internet of a volume visualization dataset contained on at least one centralized database comprising:

at least one transmitter for accepting volume visualization dataset from remote location and transmitting it securely to the centralized database;

at least one central data storage medium containing the volume visualization dataset;

a plurality of servers in communication with the at least one centralized database and capable of processing the volume visualization dataset to create virtual views based on client request;

a resource manager device for load balancing the plurality of servers;

a security device controlling the plurality of communications between a client device, and the server; including resource manager and central storage medium;

at least one physically secured site for housing the centralized database, plurality of servers, at least a resource manager, and at least a security device;

a web application adapted to satisfy a user’s request for the three-dimensional virtual views by: a) accepting at a remote location at least one user request for a series of virtual views of the volume visualization dataset, the series of views comprising a plurality of separate view frames, the remote location having a local data storage medium for storing frames of views of the volume visualization dataset, b) determining if any frame of the requested views of the volume visualization dataset is stored on the local data storage medium, c) transmitting from the remote location to at least one of the servers a request for any frame of the requested views not stored on the local data storage medium, d) at at least one of the servers, creating the requested frames of the requested views from the volume visualization dataset in the central storage medium, e) transmitting the created frames of the requested views from at least one of the servers to the client device, f) receiving the requested views from the at least one server, and displaying to the user at the remote location the requested series of three-dimensional virtual views of the volume visualization dataset by sequentially displaying frames transmitted from at least one of the servers along with any frames of the requested series of views stored on the local data storage medium.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit’s analysis focused on whether the district court was correct in its application of the Alice two-step test for patent eligibility. This two-step framework is critical for determining whether a patent’s claims involve patent-eligible subject matter under Section 101.

In the first step of the Alice analysis, the court examines whether the claims at issue are directed to an abstract idea. For AI Visualize’s patents, the Federal Circuit assessed whether the system and method for visualizing medical scans, as claimed, merely recited an abstract concept without applying or using it in a uniquely technological manner.

The court found that the patents were primarily directed to the abstract idea of manipulating and displaying data, specifically the storage, retrieval, and graphical representation of medical imaging data. The court referenced their conclusion in Hawk Tech. Sys., LLC v. Castle Retail, LLC, 60 F.4th 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2023), noting that “converting information from one format to another . . . is an abstract idea.”

Having determined that the claims were directed to an abstract idea, the court then proceeded to step two of the Alice test, which involves determining whether the claim elements, either individually or as an ordered combination, add something significantly more to the abstract idea to transform the claim into patent-eligible subject matter. This “something more” must be an inventive concept that is not merely an instruction to implement or apply the abstract idea on a generic computer or using generic technology.

In reviewing AI Visualize’s claims, the court concluded that the methods described for processing and visualizing medical data did not involve an inventive concept sufficient to warrant patent protection. The claims were found to involve routine and conventional computer functions that are generic enough to be performed on any computer network. This included the creation of virtual views from medical data, transmitting these views over low-bandwidth networks, and enabling remote access via a web portal—none of which constituted a technological improvement over existing practices.

AI Visualize cites several sections of the specification to argue that creating virtual views offers a technical solution to a technical problem. This includes a section that explains how dynamic and static virtual views are formed by selecting related image frames from a volume visualization dataset. However, the court declined to consider details from the specification that are not specifically claimed.

Moreover, the court noted that the claimed invention did not solve a technical problem in an innovative way but rather applied a known solution (data manipulation and visualization) to a practice long prevalent in the field of computer systems.

The decision reaffirms the strict standards imposed by the Federal Circuit for patent eligibility under Section 101, emphasizing that a patent’s claims must do more than simply apply an abstract idea using conventional and well-understood applications. They must demonstrate a specific, inventive concept that enhances the technological process in a non-obvious way. This ruling highlights the challenges patent applicants face in securing protection for software-based innovations, particularly those that could be viewed as abstract ideas without clear, specific, and technologically rooted implementations.

Takeaway

- The decision reinforces the importance of demonstrating a specific, technologically rooted inventive concept in patent claims, particularly in fields involving software and data manipulation.

- Patents that broadly claim the performance of “abstract ideas” such as data retrieval and display without a clearly defined inventive mechanism are likely to face challenges under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

- It is essential to provide detailed technical descriptions in patent applications and include technological specificity in the patent claims to effectively present the unique contributions.

Tags: abstract idea > Data Manipulation > Mayo/Alice Test > patent eligibility

Federal Circuit Affirms Alice Nix of Poll-Based Networking System

| August 10, 2023

Trinity Info Media v Covalent, Inc.

Decided: July 14, 2023

Before Stoll, Bryson and Cunningham.

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed patent ineligibility of the Trinity’s poll-based networking system under Alice. The claims are directed to the abstract idea of matching based on questioning, something that a human can do. The additional features of a data processing system, computer system, web server, processor(s), memory, hand-held device, mobile phone, etc. are all generic components providing a technical environment for performing the abstract idea and do not detract from the focus of the claims being on the abstract idea. The specification also does not support a finding that the claims are directed to a technological improvement in computers, mobile phones, computer systems, etc.

Procedural History:

Trinity sued Covalent for infringing US Patent Nos. 9,087,321 and 10,936,685 in 2021. The district court granted Covalent’s 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, concluding that the asserted claims are not patent eligible subject matter under 35 USC §101. Trinity appealed.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 from the ‘321 patent is as follows:

A poll-based networking system, comprising:

a data processing system having one or more processors and a memory, the memory being specifically encoded with instructions such that when executed, the instructions cause the one or more processors to perform operations of:

receiving user information from a user to generate a unique user profile for the user;

providing the user a first polling question, the first polling question having a finite set of answers and a unique identification;

receiving and storing a selected answer for the first polling question;

comparing the selected answer against the selected answers of other users, based on the unique identification, to generate a likelihood of match between the user and each of the other users; and

displaying to the user the user profiles of other users that have a likelihood of match within a predetermined threshold.

Representative claim 2 from the ‘685 patent is as follows:

A computer-implemented method for creating a poll-based network, the method comprising an act of causing one or more processors having an associated memory specifically encoded with computer executable instruction means to execute the instruction means to cause the one or more processors to collectively perform operations of:

receiving user information from a user to generate a unique user profile for the user;

providing the user one or more polling questions, the one or more polling ques-tions having a finite set of answers and a unique identification;

receiving and storing a selected answer for the one or more polling questions;

comparing the selected answer against the selected answers of other users, based on the unique identification, to generate a likelihood of match between the user and each of the other users;

causing to be displayed to the user other users, that have a likelihood of match within a predetermined threshold;

wherein one or more of the operations are carried out on a hand-held device; and

wherein two or more results based on the likelihood of match are displayed in a list reviewable by swiping from one result to another.

Looking at the claims first, the claimed functions of (1) receiving user information; (2) providing a polling question; (3) receiving and storing an answer; (4) comparing that answer to generate a “likelihood of match” with other users; and (5) displaying certain user profiles based on that likelihood are all merely collecting information, analyzing it, and displaying certain results which fall in the “familiar class of claims ‘directed to’ a patent ineligible concept,” which a human mind could perform. The court agreed with the district court’s finding that these claims are directed to an abstract idea of matching based on questioning.

The ‘685 patent adds the further function of reviewing matches using swiping and a handheld device. These features did not alter the court’s decision. The dependent claims also added other functional variations, such as performing matching based on gender, varying the number of questions asked, displaying other users’ answers, etc. These are all trivial variations that are themselves abstract ideas. The further recitation of the hand-held device, processors, web servers, database, and a “match aggregator” did not change the “focus” of the asserted claims. Instead, such generic computer components were merely limitations to a particular environment, which did not make the claims any less abstract for the Alice/Mayo Step 1.

With regard to software-based inventions, the Alice/Mayo Step 1 inquiry “often turns on whether the claims focus on the specific asserted improvement in computer capabilities or, instead, on a process that qualifies as an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool.” In addressing this, the court looks at the specification’s description of the “problem facing the inventor.” Here, the specification framed the inventor’s problem as how to improve existing polling systems, not how to improve computer technology. As such, the specification confirms that the invention is not directed to specific technological solutions, but rather, is directed to how to perform the abstract idea of matching based on progressive polling.

Under Alice/Mayo Step 2, the claimed use of general-purpose processors, match servers, unique identifications and/or a match aggregator is merely to implement the underlying abstract idea. The specification describes use of “conventional” processors, web servers, the Internet, etc. The court has “ruled many times” that “invocations of computers and networks that are not even arguably inventive are insufficient to pass the test of an inventive concept in the application of an abstract idea.” And, no inventive concept is found where claims merely recite “generic features” or “routine functions” to implement an underlying abstract idea.

Trinity’s Argument 1

Claim construction and fact discovery was necessary, but not done, before analyzing the asserted claims under §101.

Federal Circuit’s Response 1

“A patentee must do more than invoke a generic need for claim construction or discovery to avoid grant of a motion to dismiss under § 101. Instead, the patentee must propose a specific claim construction or identify specific facts that need development and explain why those circumstances must be resolved before the scope of the claims can be understood for § 101 purposes.”

Trinity’s Argument 2

Under Alice/Mayo Step One, the claims included an “advance over the prior art” because the prior art did not carry out matching on mobile phones, did not employ “multiple match servers” and did not employ “match aggregators.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 2

A claim to a “new” abstract idea is still an abstract idea.

Trinity’s Argument 3

Humans cannot mentally engage in the claimed process because humans could not perform “nanosecond comparisons” and aggregate “result values with huge numbers of polls and members” nor could humans select criteria using “servers, storage, identifiers, and/or thresholds.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 3

The asserted claims do not require “nanosecond comparisons” nor “huge numbers of polls and members.”

Trinity’s claims can be directed to an abstract idea even if the claims require generic computer components or require operations that a human cannot perform as quickly as a computer. Compare, for example, with Electric Power Group, where the court held the claims to be directed to an abstract idea even though a human could not detect events on an interconnected electric power grid in real time over a wide area and automatically analyze the events on that grid. Likewise, in ChargePoint (electric car charging network system), claims directed to enabling “communication over a network” were abstract ideas even though a human could not communicate over a computer network without the use of a computer.

Trinity’s Argument 4

Claims are eligible inventions directed to improvements to the functionality of a computer or to a network platform itself.

Federal Circuit’s Response 4

As described in the specification, mere generic computer components, e.g., a conventional computer system, server, web server, data processing system, processors, memory, mobile phones, mobile apps, are used. Such generic computer components merely provide a generic technical environment for performing an abstract idea. The specification does not describe the invention of swiping or improving on mobile phones. Indeed, the ‘685 patent describes the “advent of the internet and mobile phones” as allowing the establishment of a “plethora” or “mobile apps.” As such, “the specification does not support a finding that the claims are directed to a technological improvement in computer or mobile phone functionality.”

Trinity’s Argument 5

The district court failed to properly consider the comparison of selected answers against other uses “based on the unique identification” which was a “non-traditional design” that allowed for “rapid comparison and aggregation of result values even with large numbers of polls and members.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 5

Use of a “unique identifier” does not render an abstract idea any less abstract.

On the other hand, the “non-traditional design” appears to be based on use of an “in-memory, two-dimensional array” that “provides for linear speed across multiple match servers” and permits “an immediate comparison to determine if the user had the same answer to that of another user.” However, the asserted claims do not require any such in-memory, two-dimensional array.

Trinity’s Argument 6

The district court failed to properly consider the generation of a likelihood of a match “within a predetermined threshold.” Without this consideration, “there would be no limit or logic associated with the volume or type of results a user would receive.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 6

This merely addresses the kind of data analysis that the abstract idea of matching would include, namely how many answers should be the same before declaring a match. This does not change the focus of the claimed invention from the abstract idea of matching based on questioning.

Trinity’s Argument 7

There is an inventive concept under Alice/Mayo Step 2 because the claims recite steps performed in a “non-traditional system” that can “rapidly connect multiple users using progressive polling that compare[s] answers in real time based on their unique identification (ID) (and in the case of the ’685 patent employ swiping)” which “represents a significant advance over the art.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 7

These conclusory assertions are insufficient to demonstrate an inventive concept. “We disregard conclusory statements when evaluating a complaint under Rule 12(b)(6).”

Takeaways:

The evisceration of software-related inventions as abstract ideas continues. Although the court looks at the “claimed advance over the prior art” in assessing the “directed to” inquiry under Alice Step 1, conclusory assertions of advances over the prior art are insufficient to demonstrate inventive concept under Alice Step 2, at least for a 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss. It remains to be seen what type of description of an “advance over the prior art” would not be “conclusory” and satisfy the “significantly more” inquiry to be an inventive concept under Alice Step 2.

The one glimmer of hope for the patentee might have been the use of an “in-memory, two-dimensional array” that “provides for linear speed across multiple match servers.” An example of patent eligibility based on use of such logical structures can be found in Enfish. However, if the specification does not describe this use of an in-memory two-dimensional array and the “technological” improvement resulting therefrom to be the “focus” of the invention, even this feature might not be enough to survive § 101.

Throwing in Kitchen Sink on 101 Legal Arguments Didn’t Help Save Patent from Alice Ax

| November 21, 2022

In Re Killian

Taranto, Clevenger, Chen (August 23, 2022).

Summary:

Killian’s claim to “determining eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance [SSDI] benefits through a computer network” was deemed “clearly patent ineligible in view of our precedent.” However, the Federal Circuit also disposes of a host of the appellant’s legal challenges to 101 jurisprudence, including:

(A) all court and Board decisions finding a claim patent ineligible under Alice/Mayo is arbitrary and capricious under the APA;

(B) comparing this case to other cases in which this court and the Supreme Court considered issues of patent eligibility under 101 violates the appellant’s due process rights because Mr. Killian had no opportunity to appear in those other cases;

(C) the search for an “inventive concept” at Alice Step 2 is improper because Congress did away with an “invention” requirement when it enacted the Patent Act of 1952;

(D) “mental steps” ineligibility has no foundation in modern patent law; and

(E) there is no substantial evidence to support the rejections in view of the PTAB’s “evidentiary vacuum” in assessing the factual inquiry into whether the claimed process is well-understood, routine, and conventional.

Procedural History:

The PTAB’s affirmance of the examiner’s final rejection of Killian’s US Patent Application No. 14/450,024 under 35 USC §101 was appealed to the Federal Circuit and was upheld.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 is as follows:

A computerized method for determining eligibility for social security disability insurance (SSDI) benefits through a computer network, comprising the steps of:

(a) providing a computer processing means and a computer readable media;

(b) providing access to a Federal Social Security database through the computer network, wherein the Federal Social Security database provides records containing information relating to a person’s status of SSDI and/or parental and/or marital information relating to SSDI benefit eligibility;

(c) selecting at least one person who is identified as receiving treatment for developmental disabilities and/or mental illness;

(d) creating an electronic data record comprising information relating to at least the identity of the person and social security number, wherein the electronic data record is recorded on the computer readable media;

(e) retrieving the person’s Federal Social Security record containing information relating to the person’s status of SSDI benefits;

(f) determining whether the person is receiving SSDI benefits based on the SSDI status information contained within the Federal Social Security database record through the computer network; and

(g) indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is receiving SSDI benefits or is not receiving SSDI benefits.

The court agreed with the PTAB that the thrust of this claim is “the collection of information from various sources (a Federal database, a State database, and a caseworker) and understanding the meaning of that information (determining whether a person is receiving SSDI benefits and determining whether they are eligible for benefits under the law).” Collecting information and “determining” whether benefits are eligible are mental tasks humans routinely do. That these steps are performed on a generic computer or “through a computer network” does not save these claims from being directed to an abstract idea under Alice step 1. Under Alice step 2, this is merely reciting an abstract idea and adding “apply it with a computer.” The claims do not recite any technological improvement in how a computer goes about “determining” eligibility for benefits. Merely comparing information against eligibility requirements is what humans seeking benefits would do with or without a computer.

The court also addresses appellant’s further challenges (A)-(E) as follows.

- all court and Board decisions finding a claim patent ineligible under Alice/Mayo is arbitrary and capricious under the APA

The standards of review in the APA do not apply to decisions by courts. The APA governs judicial review of “agency action.”

There was also an assertion that there is a Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause violation stemming from the imprecision of the Alice/Mayo standard. However, the court noted that Killian never argued that the Alice/Mayo standard runs afoul of the “void-for-vagueness doctrine” and could not have argued this because this case was not even a close call (vagueness as applied to the particular case is a prerequisite to establishing facial vagueness).

As for Board decisions finding patents ineligible as being arbitrary and capricious under the APA, “we may not announce that the Board acts arbitrarily and capriciously merely by applying binding judicial precedent.” This would be akin to using the APA to attack the Supreme Court’s interpretations of 101. However, “the APA does not empower us to review decisions of ‘the courts of the United States’ because they are not agencies.”

Mr. Killian also requested “a single non-capricious definition or limiting principle” for “abstract idea” and “inventive concept.” However, the court points out that there is “no single, hard-and-fast rule that automatically outputs an answer in all contexts” because there are different types of abstract ideas (mental processes, methods of organizing human activity, claims to results rather than a means of achieving the claimed result). Nevertheless, guidance has been provided (citing several cases).

And even if the Alice/Mayo framework is unclear, “both this court and the Board would still be bound to follow the Supreme Court’s §101 jurisprudence as best we can as we must follow the Supreme Court’s precedent unless and until it is overruled by the Supreme Court.”

- comparing this case to other cases in which this court and the Supreme Court considered issues of patent eligibility under 101 violates the appellant’s due process rights because Mr. Killian had no opportunity to appear in those other cases

Examination of and comparison to earlier caselaw is just classic common law methodology for deciding cases arising under 101. “Nothing stops Mr. Killian from identifying any important distinctions between his claimed invention and claims we have analyzed in prior cases.”

- the search for an “inventive concept” at Alice Step 2 is improper because Congress did away with an “invention” requirement when it enacted the Patent Act of 1952

First, Killian has not established that Alice Step 2’s “inventive concept” is the same thing as the “invention” requirement in the Patent Act of 1952. It is not. For instance, there is no requirement to ascertain the “degree of skill and ingenuity” possessed by one of ordinary skill in the art under Alice Step 2. In any event, the Supreme Court required the “inventive concept” inquiry at Step 2, and so, “search for an inventive concept we must.”

- “mental steps” ineligibility has no foundation in modern patent law

“This argument is plainly incorrect” (citing Benson, Mayo, Diehr, Bilski, etc.). “[W]e are bound by our precedential decisions holding that steps capable of performance in the human mind are, without more, patent-ineligible abstract ideas.”

- there is no substantial evidence to support the rejections in view of the PTAB’s “evidentiary vacuum” in assessing the factual inquiry into whether the claimed process is well-understood, routine, and conventional

Substantial evidence supported the PTAB’s decision regarding Alice Step 2. The additional elements of a computer processor and a computer readable media are generic, as the application itself admits (the PTAB cited to the specification’s description about how the claimed method “may be performed by any suitable computer system”). And, the claimed “creating an electronic data record,” “indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is receiving SSDI adult child benefits,” “providing a caseworker display system,” “generating a data collection input screen,” “indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is eligible for SSDI adult child benefits,” and other data tasks are merely selection and manipulation of information – are not a transformative inventive concept.

Mr. Killian also refers to 55 documents allegedly presented to the examiner and the PTAB. But, because these were not included in the joint appendix and nothing is explained on appeal as to what these 55 documents show, “Mr. Killian forfeited any argument on appeal based on those fifty-five documents by failing to present anything more than a conclusory, skeletal argument.”

Takeaways:

Given the continued dissatisfaction over the court’s eligibility guidance and the frustration over the Supreme Court’s refusal to take on §101 since Alice, this decision offers a rare insight into the court’s position on various §101 legal challenges. For instance, this decision appears to suggest a potential Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause violation stemming from the imprecision of the Alice/Mayo standard, but only for a “close call” case where vagueness can be established for the particular case, in order to challenge the facial vagueness of the Alice/Mayo standard under the “void-for-vagueness doctrine.”

Quality and Quantity of Specification Support in Determining Patent Eligibility

| March 19, 2021

Simio, LLC v Flexsim Software Products, Inc.

December 29, 2020

Prost, Clevenger, and Stoll

Summary:

In upholding a district court’s finding of patent ineligibility for a computer-based system for object-oriented simulation, the Federal Circuit uses a new “quality and quantity” assessment of the specification’s description of an asserted claim limitation that supposedly supports the claim being directed to an improvement in computer functionality (and not an abstract idea). Here, numerous portions of the specification emphasized an improvement for a user to build object-oriented models for simulation using graphics, without the need to do any programming. This supported the court’s finding that the character of the claim as a whole is directed to an abstract idea – of using graphics instead of programming to create object-oriented simulation models. In contrast to the numerous specification descriptions supporting the abstract idea focus of the patent, one claimed feature that Simio asserted as reflecting an improvement in computer functionality was merely described in just one instance in the specification. This “disparity in both quality and quantity” between the specification support of the abstract idea versus the specification support for the asserted claim feature does not change the claim as a whole as being directed to the abstract idea.

Procedural History:

Simio, LLC sued FlexSim Software Products, Inc. for infringing U.S. Patent No. 8,156,468 (the ‘468 patent). FlexSim moved for judgment on the pleadings under Rule 12(b)(6) for failing to state a claim upon which relief could be granted because the claims of the ‘468 patent are patent ineligible under 35 USC § 101. The district court granted that motion and dismissed the case. The Federal Circuit affirmed.

Background:

Representative claim 1 of the ‘417 patent follows:

A computer-based system for developing simulation models on a physical computing device, the system comprising:

one or more graphical processes;

one or more base objects created from the one or more graphical processes,

wherein a new object is created from a base object of the one or more base objects by a user by assigning the one or more graphical processes to the base object of the one or more base objects;

wherein the new object is implemented in a 3-tier structure comprising:

an object definition, wherein the object definition includes a behavior,

one or more object instances related to the object definition, and

one or more object realizations related to the one or more object instances;

wherein the behavior of the object definition is shared by the one or more object instances and the one or more object realizations; and

an executable process to add a new behavior directly to an object instance of the one or more object instances without changing the object definition and the added new behavior is executed only for that one instance of the object.

Computer-based simulations can be event-oriented, process-oriented, or object-oriented. Earlier object-oriented simulation platforms used programming-based tools that were “largely shunned by practitioners as too complex” according to the ‘468 patent. Use of graphics emerged in the 1980s and 1990s to simplify building simulations, via the advent of Microsoft Windows, better GUIs, and new graphically based tools. Along this graphics trend, the ‘468 patent focuses on making object-oriented simulation easier for users to build simulations using graphics, without any need to write programming code to create new objects.

Decision:

Under Alice step one’s “directed to” inquiry, the court asks “what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art.” To answer this question, the court focuses on the claim language itself, read in light of the specification.

Here, the preamble relates the claim to “developing simulation models,” and the body of the claim recites “one or more graphical processes,” “one or more base objects created from the one or more graphical processes,” and “wherein a new object is created from a base object … by assigning the one or more graphical processes to the base object…” There is also the last limitation (the “executable-process limitation”). Although other limitations exist, Simio did not rely on them for its eligibility arguments.

The court considered these limitations in view of the specification. The ‘468 patent acknowledged that using graphical processes to simplify simulation building has been done since the 1980s and 1990s. And, the ‘468 patent specification states:

“Objects are built using the concepts of object-orientation. Unlike other object-oriented simulation systems, however, the process of building an object in the present invention is simple and completely graphical. There is no need to write programming code to create new objects.” ‘468 patent, column 8, lines 22-26 (8:22-26).

“Unlike existing object-oriented tools that require programming to implement new objects, Simio™ objects can be created with simple graphical process flows that require no programming.” 4:39-42.

“By making object building a much simpler task that can be done by non-programmers, this invention can bring an improved object-oriented modeling approach to a much broader cross-section of users.” 4:47-50.

“The present invention is designed to make it easy for beginning modelers to build their own intelligent objects … Unlike existing object-based tools, no programming is required to add new objects.” 6:50-53.

“In the present invention, a graphical modeling framework is used to support the construction of simulation models designed around basic object-oriented principles.” 8:60-62.

“In the present invention, this logic is defined graphically … In other tools, this logic is written in programming languages such as C++ or Java.” 9:67-10:3.

Taking the claim limitations, read in light of the specification, the court concludes that the key advance is simply using graphics instead of programming to create object-oriented simulations. “Simply applying the already-widespread practice of using graphics instead of programming to the environment of object-oriented simulations is no more than an abstract idea.” “And where, as here, ‘the abstract idea tracks the claim language and accurately captures what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance …, characterizing the claim as being directed to an abstract idea is appropriate.’”

Simio argued that claim 1 “improves on the functionality of prior simulation systems through the use of graphical or process modeling flowcharts with no programming code requited.” However, an improvement emphasizing “no programming code required” is an improvement for a user – not an improvement in computer functionality. An improvement in a user’s experience (not having to write programming code) while using a computer application does not transform the claims to be directed to an improvement in computer functionality.

Simio also argued that claim 1 improves a computer’s functionality “by employing a new way of customized simulation modeling with improved processing speed.” However, improved speed or efficiency here is not that of the computer, but rather that of the user’s ability to build or process simulation models faster using graphics instead of programming. In other words, the improved speed or efficiency is not that of computer functionality, but rather, a result of performing the abstract idea with well-known structure (a computer) by a user.

Simio finally argued that the last limitation, the executable-process limitation reflects an improvement to computer functionality. It is with regard to this last argument that the court introduces a new “quality and quantity” assessment of the specification. In particular, the court noted that “this limitation does not, by itself, change the claim’s ‘character as a whole’ from one directed to an abstract idea to one that’s not.” As support of this assessment of the claim’s “character as a whole,” the court cited to at least five instances of the specification emphasizing graphical simulation modeling making model building easier without any programming, in contrast to a single instance of the specification describing the executable process limitation:

Compare, e.g., ’468 patent col. 4 ll. 29–42 (noting that “the present invention makes model building dramatically easier,” as “Simio™ objects” can be created with graphics, requiring no programming), and id. at col. 4 ll. 47–50 (describing “this invention” as one that makes object-building simpler, in that it “can be done by non-programmers”), and id. at col. 6 ll. 50–53 (describing “[t]he present invention” as one requiring no programming to build objects), and id. at col. 8 ll. 23–26 (“Unlike other object-oriented simulation systems, however, the process of building an object in the present invention is simple and completely graphical. There is no need to write programming code to create new objects.”), and id. at col. 8 ll. 60–62 (“In the present invention, a graphical modeling frame-work is used to support the construction of simulation models designed around basic object-oriented principles.”), with col. 15 l. 45–col. 16 l. 6 (describing the executable-process limitation). This disparity—in both quality and quantity—between how the specification treats the abstract idea and how it treats the executable-process limitation suggests that the former remains the claim’s focus.

Even Simio’s own characterization of the executable-process limitation closely aligns with the abstract idea: (a) that the limitation reflects that “a new behavior can be added to one instance of a simulated object without the need for programming” and (b) that the limitation reflects an “executable process that applies the graphical process to the object (i.e., by applying only to the object instance not to the object definition).” Although this is more specific than the general abstract idea of applying graphics to object-oriented simulation, this merely repeats the above-noted focus of the patent on applying graphical processes to objects and without the need for programming. As such, this executable-process limitation does not shift the claim’s focus away from the abstract idea.

At Alice step two, Simio argued that the executable-process limitation provides an inventive concept. However, during oral arguments, Simio conceded that the functionality reflected in the executable-process limitation was conventional or known in object-oriented programming. In particular, implementing the executable process’s functionality through programming was conventional or known. Doing so through graphics does not confer an inventive concept. What Simio relies on is just the abstract idea itself – use of graphics in object-oriented simulation. Reliance on the abstract idea itself cannot supply the inventive concept that renders the invention “significantly more” than that abstract idea.

Even if the use of graphics instead of programming to create object-oriented simulations is new, a claim directed to a new abstract idea is still an abstract idea – lacking any meaningful application of the abstract idea sufficient to constitute an inventive concept to save the claim’s eligibility.

Takeaways:

- This case serves a good reminder of the importance of proper specification drafting to address 101 issues such as these. An “improvement” that can be deemed an abstract idea (e.g., use graphics instead of programming) will not help with patent eligibility. The focus of an “improvement” to support patent eligibility must be technological (e.g., in order to use graphics instead of programming in object-oriented simulation modeling, this new xyz procedure/data structure/component replaces the programming interface previously required…). “Technological” is not to be confused with being “technical” – which could mean just disclosing more details, albeit abstract idea type of details that will not help with patent eligibility. Here, even a “new” abstract idea does not diminish the claim still being “directed to” that abstract idea, nor rise to the level of an inventive concept. Improving user experience is not technological. Improving a user’s speed and efficiency is not technological. Improving computer functionality by increasing its processing speed and efficiency could be sufficiently technological IF the specification explains HOW. Along the lines of Enfish, perhaps new data structures to handle a new interface between graphical input and object definitions may be a technological improvement, again, IF the specification explains HOW (and if that “HOW” is claimed). In my lectures, a Problem-Solution-Link methodology for specification drafting helps to survive patent eligibility. Please contact me if you have specification drafting questions.

- This case also serves as a good reminder to avoid absolute statements such as “the present invention is …” or “the invention is… .” There is caselaw using such statements to limit claim interpretation. Here, it was used to ascertain the focus of the claims for the “directed to” inquiry of Alice step one. The more preferrable approach is the use of more general statements, such as “at least one benefit/advantage/improvement of the new xyz feature is to replace the previous programming interface with a graphical interface to streamline user input into object definitions…”

- This decision’s “quality and quantity” assessment of the specification’s focus on the executable-process limitation provides a new lesson. Whatever is the claim limitation intended to “reflect” an improvement in technology, there should be sufficient specification support for that claim limitation – in quality and quantity – for achieving that technological improvement. Stated differently, the key features of the invention must not only be recited in the claim, but also, be described in the specification to achieve the technological improvement, with an explanation as to why and how.

- This is yet another unfortunate case putting the Federal Circuit’s imprimatur on the flawed standard to find the “the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” in Alice step one, albeit not as unfortunate as Chamberlain v Techtronic (certiorari denied) or American Axle v Neapco (still pending certiorari). In another lecture, I explain why the “claimed advance” standard is problematic and why it contravenes Supreme Court precedent. Briefly, the claimed advance standard is like the “gist” or “heart” of the invention standard of old that was nixed. In Aro Mfg. Co. v. Convertible Top Replacement Co., the Supreme Court stated that “there is no legally recognizable or protected ‘essential’ element, ‘gist’ or ‘heart’ of the invention in a combination patent.” In §§102 and 103 issues, the Federal Circuit said distilling an invention down to its “gist” or “thrust” disregards the claim “as a whole” requirement. Likewise, stripping the claim of all its known features down to its “claimed advance over the prior art” is also contradictory to the same requirement to consider the claim as a whole under section 101. Moreover, the claimed advance standard contravenes the Supreme Court’s warnings in Diamond v Diehr that “[i]t is inappropriate to dissect the claims into old and new elements and then to ignore the presence of the old elements in the analysis. … [and] [t]he ‘novelty’ of any element or steps in a process, or even of the process itself, is of no relevance in determining whether the subject matter of a claim falls within the 101 categories of possibly patentable subject matter.” Furthermore, the origins of the claimed advance standard have not been vetted. Originally, the focus was on finding a practical application of an abstract idea in the claim. This search for a practical application morphed, without proper legal support, into today’s claimed advance focus in Alice step one. Interestingly enough, since the 2019 PEG, the USPTO has not substantively revised its subject matter eligibility guidelines to incorporate any of the recent “claimed advance” Federal Circuit decisions.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 101 > abstract idea > patent eligibility > specification drafting

Motion detection system found to be ineligible patent subject matter

| February 18, 2021

iLife Technologies v. Nintendo

January 13, 2021

Moore, Reyna and Chen. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

iLife sued Nintendo for infringing its patent to a motion detection system. Claim 1 of the patent recites a motion detection system that evaluates relative movement of a body based on both dynamic and static acceleration, and a processor that determines whether body movement is within environmental tolerance and generates tolerance indica, and then the system transmits the tolerance indica. In granting Nintendo’s motion for JMOL, the district court held that claim 1 of iLife’s patent is directed to patent ineligible subject matter under § 101. The CAFC affirmed the district court stating that claim 1 of the patent is directed to the abstract idea of “gathering, processing, and transmitting information” and no other elements of claim 1 transform the nature of the claim into patent-eligible subject matter.

Details:

The patent at issue in this case is U.S. Patent No. 6,864,796 to a motion detection system owned by iLife. iLife sued Nintendo for infringement of claim 1 of the ‘796 patent. Claim 1 of the ‘796 patent is provided:

1. A system within a communications device capable of evaluating movement of a body relative to an environment, said system comprising:

a sensor, associable with said body, that senses dynamic and static accelerative phenomena of said body, and

a processor, associated with said sensor, that processes said sensed dynamic and static accelerative phenomena as a function of at least one accelerative event characteristic to thereby determine whether said evaluated body movement is within environmental tolerance

wherein said processor generates tolerance indicia in response to said determination; and

wherein said communication device transmits said tolerance indicia.

Nintendo moved for summary judgment arguing that claim 1 is directed to patent ineligible subject matter. The district court declined to decide the eligibility issue on summary judgment and the case proceeded to a jury trial. After a jury verdict in favor of iLife, Nintendo moved for a judgment as a matter of law (JMOL) again arguing patent ineligibility. The district court granted Nintendo’s motion for JMOL holding that claim 1 is directed to ineligible subject matter.

The CAFC followed the two-step test under Alice for determining patent eligibility.

1. Determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas. If so, proceed to step 2.

2. Examine the elements of each claim both individually and as an ordered combination to determine whether the claim contains an inventive concept sufficient to transform the nature of the claims into a patent-eligible application. If the claim elements involve well-understood, routine and conventional activity they do not constitute an inventive concept.

Under step one, iLife argued that claim 1 is not directed to an abstract idea because claim 1 recites “a physical system that incorporates sensors and improved techniques for using raw sensor data” in attempt to analogize with Thales Visionix Inc. v. United States, 850 F.3d 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2017) and Cardio-Net, LLC v. InfoBionic, Inc., 955 F.3d 1358 (Fed. Cir. 2020). However, the CAFC distinguished Thales because in Thales, “the claims recited a particular configuration of inertial sensors and a specific choice of reference frame in order to more accurately calculate position and orientation of an object on a moving platform.” The court in Thales held that the claims were directed to an unconventional configuration of sensors.”

The CAFC also distinguished Cardio-Net because the claims in that case were “focused on a specific means or method that improved cardiac monitoring technology, improving the detection of, and allowing more reliable and immediate treatment of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter.” The CAFC started that claim 1 of the ‘796 patent “is not focused on a specific means or method to improve motion sensor systems, nor is it directed to a specific physical configuration of sensors.” Thus, the CAFC concluded that claim 1 is directed to the abstract idea of “gathering, processing, and transmitting information.”

Under step two, the CAFC stated that “[a]side from the abstract idea, the claim recites only generic computer components, including a sensor, a processor, and a communication device.” The CAFC also reviewed the specification finding that these elements are all generic. iLife attempted to argue that “configuring an acceleration-based sensor and processor to detect and distinguish body movement as a function of both dynamic and static acceleration is an inventive concept.” But the CAFC pointed out that the specification describes that sensors that measure both static and dynamic acceleration were known. The CAFC further stated that “claim 1 does not recite any unconventional means or method for configuring or processing that information to distinguish body movement based on dynamic and static acceleration. Thus, the CAFC concluded that merely sensing and processing static and dynamic acceleration information using generic components “does not transform the nature of claim 1 into patent eligible subject matter.”

Comments

When drafting patent applications, make sure to include specific details for performing particular functions and/or specific configurations. Claims including details about performing functions or about specific configurations will have a better chance to survive step one of the Alice test for patent eligibility. The specification should also include descriptions of why the specific functions or configurations provide improvements over the prior art to be able to show that the claims provide an “inventive concept” under step two of Alice.

The CAFC’s Holding that Claims are Directed to a Natural Law of Vibration and, thus, Ineligible Highlights the Shaky Nature of 35 U.S.C. 101 Evaluations

| November 1, 2019

American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. v. Neapco Holdings, LLC

October 9, 2019

Opinion by: Dyke, Moore and Taranto (October 3, 2019).

Dissent by: Moore.

Summary:

American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. (AAM) sued Neapco Holdings, LLC (Neapco) for alleged infringement of U.S. Patent 7,774,911 for a method of manufacturing driveline propeller shafts for automotive vehicles. On appeal, the Federal Circuit upheld the District Court of Delaware’s holding of invalidity under 35 U.S.C. 101. The Federal Circuit explained that the claims of the patent were directed to the desired “result” to be achieved and not to the “means” for achieving the desired result, and, thus, held that the claims failed to recite a practical way of applying underlying natural law (e.g., Hooke’s law related to vibration and damping), but were instead drafted in a results-oriented manner that improperly amounted to encompassing the natural law.

Details:

- Background

The case relates to U.S. Patent 7,774,911 of American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. (AAM) which relates to a method for manufacturing driveline propeller shafts (“propshafts”) with liners that are designed to attenuate vibrations transmitted through a shaft assembly. Propshafts are employed in automotive vehicles to transmit rotary power in a driveline. During use, propshafts are subject to excitation or vibration sources that can cause them to vibrate in three modes: bending mode, torsion mode, and shell mode.

The CAFC focused on independent claims 1 and 22 as being “representative” claims, noting that AAM “did not argue before the district court that the dependent claims change the outcome of the eligibility analysis.”

| Claim 1 | Claim 22 |

| 1. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising: providing a hollow shaft member; tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member; and positioning the at least one liner within the shaft member such that the at least one liner is configured to damp shell mode vibrations in the shaft member by an amount that is greater than or equal to about 2%, and the at least one liner is also configured to damp bending mode vibrations in the shaft member, the at least one liner being tuned to within about ±20% of a bending mode natural frequency of the shaft assembly as installed in the driveline system. | 22. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising: providing a hollow shaft member; tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner, and inserting the at least one liner into the shaft member; wherein the at least one liner is a tuned resistive absorber for attenuating shell mode vibrations and wherein the at least one liner is a tuned reactive absorber for attenuating bending mode vibrations. |

As explained by the CAFC, “[i]t was known in the prior art to alter the mass and stiffness of liners to alter their frequencies to produce dampening,” and “[a]ccording to the ’911 patent’s specification, prior art liners, weights, and dampers that were designed to individually attenuate each of the three propshaft vibration modes — bending, shell, and torsion — already existed.” The court further explained that in the ‘911 patent “these prior art damping methods were assertedly not suitable for attenuating two vibration modes simultaneously,” i.e., “shell mode vibration [and] bending mode vibration,” but “[n]either the claims nor the specification [of the ‘911 patent] describes how to achieve such tuning.”

The District Court concluded that the claims were directed to laws of nature: Hooke’s law and friction damping. And, the District Court held that the claims were ineligible under 35 U.S.C. 101. AAM appealed.

- The CAFC’s Decision

Under 35 U.S.C. 101, “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof” may be eligible to obtain a patent, with the exception long recognized by the Supreme Court that “laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable.”

Under the Supreme Court’s Mayo and Alice test, a 101 analysis follows a two-step process. First, the court asks whether the claims are directed to a law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea. Second, if the claims are so directed, the court asks whether the claims embody some “inventive concept” – i.e., “whether the claims contain an element or combination of elements that is sufficient to ensure that the patent in practice amounts to significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself.”

At step-one, the CAFC explained that to determine what the claims are directed to, the court focuses on the “claimed advance.” In that regard, the CAFC noted that the ‘911 patent discloses a method of manufacturing a driveline propshaft containing a liner designed such that its frequencies attenuate two modes of vibration simultaneously. The CAFC also noted that AAM “agrees that the selection of frequencies for the liners to damp the vibrations of the propshaft at least in part involves an application of Hooke’s law, which is a natural law that mathematically relates mass and/or stiffness of an object to the frequency that it vibrates. However, the CAFC also noted that “[a]t the same time, the patent claims do not describe a specific method for applying Hooke’s law in this context.”

The CAFC also noted that “even the patent specification recites only a nonexclusive list of variables that can be altered to change the frequencies,” but the CAFC emphasized that “the claims do not instruct how the variables would need to be changed to produce the multiple frequencies required to achieve a dual-damping result, or to tune a liner to dampen bending mode vibrations.”

The CAFC explained that “the claims general instruction to tune a liner amounts to no more than a directive to use one’s knowledge of Hooke’s law, and possibly other natural laws, to engage in an ad hoc trial-and-error process … until a desired result is achieved.”

The CAFC explained that the “distinction between results and means is fundamental to the step 1 eligibility analysis, including law-of-nature cases.” The court emphasized that “claims failed to recite a practical way of applying an underlying idea and instead were drafted in such a results-oriented way that they amounted to encompassing the [natural law] no matter how implemented.

At step-two, the CAFC stated that “nothing in the claims qualifies as an ‘inventive concept’ to transform the claims into patent eligible matter.” The CAFC explained that “this direction to engage in a conventional, unbounded trial-and-error process does not make a patent eligible invention, even if the desired result … would be new and unconventional.” As the claims “describe a desired result but do not instruct how the liner is tuned to accomplish that result,” the CAFC affirmed that the claims are not eligible under step two.

NOTE: In response to Judge Moore’s dissent, the CAFC explained that the dissent “suggests that the failure of the claims to designate how to achieve the desired result is exclusively an issue of enablement.” However, the CAFC expressed that “section 101 serves a different function than enablement” and asserted that “to shift the patent-eligibility inquiry entirely to later statutory sections risks creating greater legal uncertainty, while assuming that those sections can do work that they are not equipped to do.”

- Judge Moore’s Dissent

Judge Moore strongly dissented against the majority’s opinion. Judge Moore argued, for example, that:

- “The majority’s decision expands § 101 well beyond its statutory gate-keeping function and the role of this appellate court well beyond its authority.”

- “The majority’s concern with the claims at issue has nothing to do with a natural law and its preemption and everything to do with concern that the claims are not enabled. Respectfully, there is a clear and explicit statutory section for enablement, § 112. We cannot convert § 101 into a panacea for every concern we have over an invention’s patentability.”

- “Section 101 is monstrous enough, it cannot be that now you need not even identify the precise natural law which the claims are purportedly directed to.” “The majority holds that they are directed to some unarticulated number of possible natural laws apparently smushed together and thus ineligible under § 101.”

- “The majority’s validity goulash is troubling and inconsistent with the patent statute and precedent. The majority worries about result-oriented claiming; I am worried about result-oriented judicial action.”

Takeaways:

- When drafting claims, be mindful to avoid drafting a “result-oriented” claim that merely recites a desired “result” of a natural law or natural phenomenon without including specific steps or details setting establishing “how” the results are achieved.

- When drafting claims, be mindful that although under 35 U.S.C. 112 supportive details satisfying enablement are only required to be within the written specification, under 35 U.S.C. 101 supportive details satisfying eligibility must be within the claims themselves.

A treatment method including an administering step based on discovery of a natural law is patentable eligible

| June 18, 2019

Endo pharmaceuticals, Et Al. v. Teva pharmaceuticals Et Al.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s decision holding the claims of U.S. Patent No. 8,808,737 ineligible under 35 U.S.C. §101. The Federal Circuit held that the claims at issue are not directed to a natural law.

Details

Endo owns the ‘737 patent, entitled “method of treating pain utilizing controlled release oxymorphone pharmaceutical compositions and instruction on dosing for renal impairment.” The inventors of the ‘737 patent discovered that patients with moderately or severely impaired kidney function need less oxymorphone than usual to achieve a similar level of pain management. Accordingly, the treatment method of the ‘737 patent advantageously allows patients with renal impairment to inject less oxymorphone while still treating their pain.

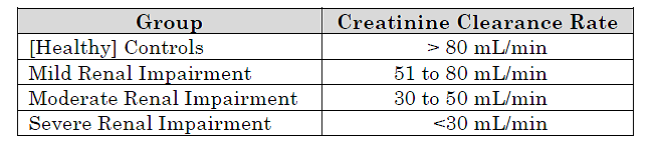

More specifically, the degree of renal impairment of the subjects can be indicated by their creatinine clearance rate. The subjects may be separated into four groups based on their creatinine clearance rates:

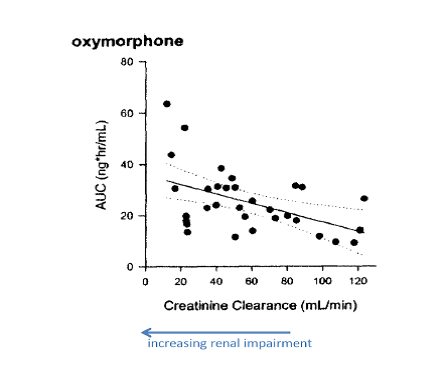

Furthermore, the inventors discover that there was a statistically significant correlation between plasma AUC (area under curve) for oxymorphone and a patient’s degree of renal impairment, as shown below:

That is, there was relatively little change in oxymorphone AUC until the subjects had moderate-to-severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance rates below 50 mL/min). Subjects with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance rates below 30 mL/min) had the highest AUC values.

Claim 1 of the ‘737 patent is as follows:

1. A method of treating pain in a renally impaired patient, comprising the steps of:

a. providing a solid oral controlled release dosage form, comprising:

a) about 5 mg to about 80 mg of oxymorphone or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof as the sole active ingredient; and

b) a controlled release matrix;

b. measuring a creatinine clearance rate of the patient and determining it to be

a) less than about 30 ml/min;

b) about 30 mL/min to about 50 mL/min;

c) about 51 mL/min to about 80 mL/min, or

d) about 80 mL/min; and

c. orally administering to said patient, in dependence on which creatinine clearance rate is found, a lower dosage of the dosage form to provide pain relief;

wherein after said administration to said patient, the average AUC of oxymorphone over a 12-hour period is less than about 21 ng·hr/mL.

The magistrate judge held, and the district court agreed, that the claims at issue were not patent-eligible because the claims are directed to the natural law that the bioavailability of oxymorphone is increased in people with severe renal impairment, and the three steps a-c do not add “significant more” to qualify as a patentable method.

However, the federal circuit disagrees with the district court, holding that the claims at issue were directed to a patent-eligible application of a natural law. Specifically, The Federal Circuit points out that “it is not enough to merely identify a patent-ineligible concept underlying the claim; we must determine whether that patent-ineligible concept is what the claim is ‘directed to.’” Applying this law, the Federal Circuit concluded that claims of the ‘737 patent are directed to a patent-eligible method of using oxymorphone or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof to treat pain in a renally impaired patient. The conclusion is supported by the claim language itself and confirmed by the specification. The claim language recites specific steps a-c in using oxymorphone to treat pain in a renally impaired patient. The specification predominantly describes the invention as a treatment method, and explains that the method avoids possible issues in dosing and allows for treatment with the lowest available dose for patients with renal impairment. That is, the inventors here recognized the relationship between oxymorphone and patients with renal impairment, but claimed an application of that relationship, which is a method of treatment including specific steps to adjust or lower the oxymorphone dose for patients with renal impairment.

Then, the Federal Circuit considered that the claims at issue are similar to those in Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. West-Ward Pharmaceuticals International Ltd, (Fed. Cir. 2018) and Rapid Litig. Mgmt. Ltd. V. CellzDirect (Fed. Cir. 2016) while distinguishing the claims at issue from those in Mayo collaborative Servs. V. Prometheus Labs., Inc. (SC 2012), and Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., (Fed. Cir. 2015). For example, the claims at issue in Vanda related to a method of treating schizophrenia patients with a drug (iloperidone), where the administered dose is adjusted based on whether or not the patient is a “CYP2D6 poor metabolizer.” Like the claims in Vanda, the claims at issue here “are directed to a specific method of treatment for specific patients using a specific compound at specific doses to achieve a specific outcome.” In contrast, the representative claim in Mayo recited administering a thiopurine drug to patient as a first step in the method before determining the natural law relationship. The administering step is not performed based on the natural law relationship, and accordingly is not an application of the natural law.

Take away

- Adding an application step such as an administering step based on discovery of a natural law will render the claims patent eligible.

- There is a potential problem of divided infringement issue here in the subsequent enforcement effort. But direct infringement against physicians and induced infringement against pharmaceutical companies have been found based on similar patent claims. Eli Lilly & Co. v. Teva Parenteral Medicines, Inc., Appeal No. 2015-2067 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 12, 2017).

More Diagnostic Patent Claims Fall—Despite following USPTO Guidelines

| May 3, 2019

Cleveland Clinic v. True Health Diagnostics

April 1, 2019

Lourie, Moore and Wallach. Opinion by Lourie. (non-precedential)

Summary

In a non-precedential opinion, the CAFC considered diagnostic patent claims ineligible. The CAFC dismissed recitation of detection of a biomarker using conventional tools as an “overly superficial” rephrasing of claims that were previously considered ineligible. The CAFC also indicated that it is not bound by USPTO guidelines, and implied that the relied-upon USPTO Example is inconsistent with Ariosa.

Details

This case relates to a diagnostic to detect heart disease. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is an early marker of heart disease associated with atherosclerotic plaques. It was known in the prior art that MPO can be detected in surgically removed plaques, but it was not known that MPO is present in elevated levels in the blood of patients having atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The inventors disclosed a method of detecting MPO by lab techniques such as colorimetric-based assay, flow cytometry, ELISA etc, and then correlating the detected MPO to heart disease. Notably, the specification states that MPO can be detected “by standard methods in the art,” and that commercially available kits can be modified to detect MPO.

In Cleveland Clinic I, the CAFC held that method claims reciting “a method of assessing risk of having atherosclerotic heart disease” were invalid as reciting a law of nature without anything significantly more. See Cleveland Clinic v. True Health Diagnostics LLC, 859 F.3d 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2017), cert. denied, 138 S. Ct. 2621, (2018). In that case, the claims only recited a step of “comparing” MPO levels of a subject with MPO levels in a known non-diseased person.

However, this case presents slightly different claims based on same technology. Rather than reciting diagnosis or treatment, the present claims recite methods of detecting and identifying elevated MPO, with more detail. Specifically, the relevant claims are as follows:

Patent 9,575,065:

1. A method of detecting elevated MPO mass in a patient sample comprising:

a) obtaining a plasma sample from a human patient having atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD); and

b) detecting elevated MPO mass in said plasma sample, as compared to a control MPO mass level from the general population or apparently healthy subjects, by contacting said plasma sample with anti-MPO antibodies and detecting binding between MPO in said plasma sample and said anti-MPO antibodies.

Patent 9,581,597:

1. A method for identifying an elevated myeloperoxidase (MPO) concentration in a plasma sample from a human subject with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease comprising: a) contacting a sample with an anti-MPO antibody, wherein said sample is a plasma sample from a human subject having atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease;

b) spectrophotometrically detecting MPO levels in said plasma sample;

c) comparing said MPO levels in said plasma sample to a standard curve generated with known amounts of MPO to determine the MPO concentration in said sample; and

d) comparing said MPO concentration in said plasma sample from said human subject to a control MPO concentration from apparently healthy human subjects, and identifying said MPO concentration in said plasma sample from said human subject as being elevated compared to said control MPO concentration.

2. The method of claim 1, further comprising, prior to step a), centrifuging an anti-coagulated blood sample from said human subject to generate said plasma sample.

Prosecution

In prosecution of these patents, the Applicant argued by analogy to Example 29 of the May 2016 USPTO eligibility guidelines. Example 29 presents two claims:

1. A method of detecting JUL-1 in a patient, said method comprising:

a. obtaining a plasma sample from a human patient; and

b. detecting whether JUL-1 is present in the plasma sample by contacting the plasma sample with an anti-JUL-1 antibody and detecting binding between JUL-1 and the antibody.

2. A method of diagnosing julitis in a patient, said method comprising:

a. obtaining a plasma sample from a human patient;

b. detecting whether JUL-1 is present in the plasma sample by contacting the plasma sample with an anti-JUL-1 antibody and detecting binding between JUL-1 and the antibody; and

c. diagnosing the patient with julitis when the presence of JUL-1 in the plasma sample is detected.

According to the 2016 guidelines, claim 1 is eligible, because it does not recite a law of nature (pass on step 2A). However, in the USPTO’s view, claim 2 is ineligible because it recites a law of nature without reciting something significantly more (fail on steps 2A and 2B).

In prosecution, the Applicant argued that the “detecting” claim of the ‘065 patent is more similar to the “detecting” claim 1 of Example 29 (eligible) than it is to the “diagnosing” claim 2 of Example 29 (ineligible). The Examiner agreed and allowed the application.

As to the ‘597 claims, the Applicant successfully argued in prosecution that the “identifying” claim recites significantly more than a judicial exception, also relying on Example 29. The Applicant argued that it was not known to identify elevated MPO in plasma of patients having atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, even though it was previously known to detect MPO in plaques. The Examiner agreed and allowed the application.

District Court

The district court interpreted the claims as being directed to a law of nature, based on the recitations of “detecting elevated MPO mass in a patient sample…”, “….from a human having atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease”, and “identifying an elevated [MPO] concentration in a plasma sample from a human subject with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.” The district court concluded that the method is only useful for detecting elevated MPO associated with cardiovascular disease. In other words, the method is only useful for detecting a natural phenomenon.

As such, the district court concluded that the claims do not recite a general laboratory technique and instead are trying to “recast [a] diagnostic patent as a laboratory method patent.” The district court concluded that the claims are directed to detecting the correlation between MPO and the disease, rather than to detecting MPO more generally. Thus, the claims fail step 2A. Further, the additional steps are all well-known and conventional and thus fail step 2B. Specifically, the district court stated that “[i]f merely using existing, conventional methods to observe a newly discovered natural phenomenon were enough to qualify for protection under §101, the natural law exception would be eviscerated.”

CAFC

The CAFC agreed in holding that the claims are ineligible. Cleveland Clinic argued first that the claims are not directed to a natural law, but rather to a technique of using an immunoassay to measure MPO. However, the CAFC considered this distinction to be “overly superficial,” and stated that the claims are directed to a natural law (correlation between MPO and the disease). The CAFC characterized the difference between the claims at issue and the claims of Cleveland Clinic I as a “rephrasing” that does not make the claims less directed to a law of nature.

Cleveland Clinic also argued that the correlation is not a natural law because it can only be detected using certain techniques. However, the CAFC saw through this, and stated that the same is true for many of the natural laws at issue in previous cases. Specifically, the CAFC stated that “[i]nadequate measures of detection do not render a natural law any less natural.”

The CAFC also held that the claims do not recite an additional inventive concept. Cleveland Clinic argued that using a known technique in a standard way to observe a natural law confers an inventive concept. However, the CAFC stated that this reasoning has been dismissed is previous cases such as Athena Diagnostics v. Mayo and Ariosa v. Sequenom. Further to this point, the CAFC stressed that the MPO is detected using known techniques without significant adjustments.

Finally, the CAFC addressed the USPTO guidelines. Cleveland Clinic stated that the district court erred by not giving appropriate deference to Example 29 noted above. The CAFC agreed with True Health in stating the USPTO guidelines are neither persuasive nor relevant to the claims at issue, because the district court reached the correct decision.

The CAFC did not include an extensive discussion of the USPTO guidelines, but stated as follows:

While we greatly respect the PTO’s expertise on all matters relating to patentability, including patent eligibility, we are not bound by its guidance. And, especially regarding the issue of patent eligibility and the efforts of the courts to determine the distinction between claims directed to natural laws and those directed to patent-eligible applications of those laws, we are mindful of the need for consistent application of our case law.

Further with regard to Example 29, the CAFC stated that its claim 1 is “strikingly similar” to ineligible claim 1 of Ariosa. As such, the CAFC stated that although they have considered Example 29 and related arguments, Ariosa must control. Thus, the CAFC did not follow the USPTO’s guidelines.

Takeaway

- Patent eligibility of diagnostic methods continues to be highly problematic. However, Chris Coons (D-DE) and Thom Tillis (R-NC) have recently been holding meetings on the issue, and released a “framework” on April 17, 2019:

However, in view of competing interests of the life sciences industry and the software industry, as well as reluctance to change a long-standing law, legislative change may be farther away than one might hope.

- One relies on USPTO guidelines at their own risk. Here, less than 3 years after publication, a CAFC panel has declined to follow the USPTO’s guidelines. Since such guidelines do not have the force of law, the courts are not required to follow them. In fact, in this case, the CAFC was somewhat dismissive of the USPTO’s efforts regarding §101. It is quite possible that the much-lauded USPTO guidelines issued on January 4, 2019 might suffer the same fate.