Revisiting KSR: “A person of ordinary skill is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton.”

| June 29, 2021

Becton, Dickinson and Company v. Baxter Corporation Englewood

Decided on May 28, 2021

Prost*, Clevenger, and Dyk. Court opinion by Dyk. (*Sharon Prost vacated the position of Chief Judge on May 21, 2021, and Kimberly A. Moore assumed the position of Chief Judge on May 22, 2021.)

Summary

On appeals from the United States Patent and Trademark Office, Patent Trial and Appeal Board in an inter partes review, the Federal Circuit unanimously revered the Board’s conclusion of non-obviousness of an asserted patent, directed to a “method for performing telepharmacy,” and a “system for preparing and managing patient-specific dose orders that have been entered into a first system.” The Federal Circuit stated that, in analysis of obviousness, a person of ordinary skill would also consider a source other than cited prior art references, and established that cancellation of all the claims of a patent does not affect the status of the patent as pre-AIA Section 102(e)(2) reference.

Details

I. Background

Becton, Dickinson and Company (“Becton”) petitioned for inter partes review of claims 1– 13 and 22 of U.S. Patent No. 8,554,579 (“the ’579 patent”), owned by Baxter Corporation Englewood (“Baxter”).

Becton asserted invalidity of the challenged claims primarily based on three prior art references: U.S. Patent No. 8,374,887 (“Alexander”), U.S. Patent No. 6,581,798 (“Liff”), and U.S. Patent Publication No. 2005/0080651 (“Morrison”).

Claims 1 and 8 are illustrative of the ’579 patent, as agreed by the parties. Claim 1 is directed to a “method for performing telepharmacy,” and claim 8 is directed to a “system for preparing and managing patient-specific dose orders that have been entered into a first system.”

There are two contested limitations on appeal: the “verification” limitation in claim 8, and the “highlighting” limitation in claims 1 and 8. Claim 8 recites three elements, an order processing server, a dose preparation station, and a display. The relevant portion of the dose preparation station in claim 8, containing both limitations, reads:

8. A system for preparing and managing patient-specific dose orders that have been entered into a first system, comprising:

a dose preparation station for preparing a plurality of doses based on received dose orders, the dose preparation station being in bi-directional communication with the order processing server and having an interface for providing an operator with a protocol associated with each received drug order and specifying a set of drug preparation steps to fill the drug order, the dose preparation station including an interactive screen that includes prompts that can be highlighted by an operator to receive additional information relative to one particular step and includes areas for entering an input;

. . . and wherein each of the steps must be verified as being properly completed before the operator can continue with the other steps of drug preparation process, the captured image displaying a result of a discrete isolated event performed in accordance with one drug preparation step, wherein verifying the steps includes reviewing all of the discrete images in the data record . . . .

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) determined that asserted claims were not invalid as obvious. While the Board found that Becton had established that one of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to combine Alexander and Liff, as well as Alexander, Liff, and Morrison, and that Baxter’s evidence of secondary considerations was weak, the Board nevertheless determined that Alexander did not teach or render obvious the verification limitation and that combinations of Alexander, Liff, and Morrison did not teach or render obvious the highlighting limitation.

Becton appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) unanimously revered the Board’s conclusion of non-obviousness because the determination regarding the verification and highlighting limitations is not supported by substantial evidence.

(i) The Verification Limitation

Alexander discloses in a relevant part: “[I]n some embodiments, a remote pharmacist may supervise pharmacy work as it is being performed. For example, in one embodiment, a remote pharmacist may verify each step as it is performed and may provide an indication to a non-pharmacist per- forming the pharmacy that the step was performed correctly. In such an example, the remote pharmacist may provide verification feedback via the same collaboration software, or via another method, such as by telephone.” Alexander, col. 9 ll. 47–54 (emphasis added).

Relying on the above-cited portion of Alexander, the Board found persuasive Baxter’s argument that Alexander “only discusses that ‘a remote pharmacist may verify each step’; not that the remote pharmacist must verify each and every step before the operator is allowed to proceed” (emphasis added).

The Court concluded that the Board’s determination that Alexander does not teach the verification limitation is not supported by substantial evidence because, among other things, the Court found it quite clear that “[i]n the context of Alexander, “may” does not mean “occasionally,” but rather that one “may” choose to systematically check each step.”

(ii) The Highlighting Limitation

Becton did not argue that Liff “directly discloses highlighting to receive additional language about a drug preparation step.” Instead, Becton argued that “Liff discloses basic computer functionality—i.e., using prompts that can be highlighted by the operator to receive additional information—that would render the highlighting limitation obvious when applied in combination with other references,” primarily Alexander.

In support of petition for inter partes review, Dr. Young testified in his declaration that Liff “teaches that the user can highlight various inputs and information displayed on the screen, as illustrated in Figure 14F.”

The Board found that Liff taught “highlight[ing] patient characteristics when dispensing a prepackaged medication.” Baxter did not contend that this aspect of the Board’s decision was erroneous.

Nevertheless, while finding that “this present[ed] a close case,” the Board determined, that “Dr. Young fail[ed] to explain why Liff’s teaching to highlight patient characteristics when dispensing a prepackaged medication would lead one of ordinary skill to highlight prompts in a drug formulation context to receive additional information relative to one particular step in that process, or even what additional information might be relevant.” In addition, the Board found that Becton’s arguments with respect to Morrison did not address the deficiency in its position based on Alexander and Liff.

In contrast, citing KSR (“[a] person of ordinary skill is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton”), the Court concluded that the Board erred in looking to Liff as the only source a person of ordinary skill would consider for what “additional information might be relevant.” The Court reached an opposite conclusion by citing following Dr. Young’s testimony:

“[a] person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood that additional information could be displayed on the tabs taught by Liff” and that “such information could have included the text of the order itself, information relating to who or how the order should be prepared, or where the or- der should be dispensed.”

“[a] medication dose order for compounding a pharmaceutical would have been accompanied by directions for how the dose should be prepared, including step-by-step directions for preparing the dose.”

(iii) An Alternative Ground

As an alternative ground to affirm the Board’s determination of non-obviousness, Baxter argues that the Board erred in determining that Alexander is prior art under 35 U.S.C. § 102(e)(2) (pre-AIA).

It is undisputed that the filing date of the application for Alexander is February 11, 2005, which is before the earliest filing date of the application for the ’579 patent, October 13, 2008; that the Alexander claims were granted; and that the application for Alexander was filed by another.

However, based on the fact that all claims in Alexander (granted on February 12, 2013) were cancelled on February 15, 2018, following inter partes review, Baxter argued that “because the Alexander ‘grant’ had been revoked, it can no longer qualify as a patent ‘granted’ as required for prior art status under Section 102(e)(2).”

The Court rejected Baxter’s argument because “[t]he text of the statute requires only that the patent be “granted,” meaning the “grant[]” has occurred. 35 U.S.C. § 102(e)(2) (pre-AIA)” and “[t]he statute [thus] does not require that the patent be currently valid.”

(iv) Secondary Considerations

The Court rejected Baxter’s argument because “Baxter does not meaningfully argue that the weak showing of secondary considerations here could overcome the showing of obviousness based on the prior art.”

Takeaway

· In analysis of obviousness, a person of ordinary skill would also consider a source other than cited prior art references (petitioner’s testimony in this case).

· Cancellation of all the claims of a patent does not affect the status of the patent as pre-AIA Section 102(e)(2) reference.

If it cannot be made, it does not exist!

| May 11, 2021

Raytheon Technologies Corp. v. General Electric Co. (Fed. Cir. 2021)

Decided on April 16, 2021

Lourie, Hughes, and Chen (author).

Summary:

“A typical obviousness inquiry often turns on whether an asserted prior art reference teaches a particular disputed claim limitation or whether a skilled artisan would have been motivation at the time of the invention to combine the teachings of difference references.” In this case, the court tackled the question of enabling disclosure in the prior art reference, and what is required.

Raytheon owned U.S. Patent 9,695,751 (herein ‘751) directed to gas turbine engines. Raytheon appealed a final inter partes review decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (the Board) finding claims 3 and 16 where unpatentable as obvious in view of the reference Knip. Claims 3 and 16 where the only pending claims after Raytheon disclaimed all other claims cited in the inter partes review.

“[T]he ‘751 patent generally claims a geared gas turbine engine with two turbines and a specific number of fan blades and turbine rotors and/or stages.” Further, the “key distinguishing feature of the claims is the recitation of a power density range that the patent describes as being ‘much higher than in the prior art.'”

Knip is a 1987 NASA technical memorandum that envisions superior performance characteristics for an imagined “advanced [turbofan] engine” “incorporating all composite materials.” Such a construction was undisputedly unattainable at that time, [but] an imagined application of these “revolutionary” composite materials to a turbofan engine allowed the author of Knip to assume aggressive performance parameters for an “advanced” engine including then-unachievable pressure ratios and turbine temperatures.” Although the reference discloses numerous performance parameters, it did not explicitly disclose SLTO thrust, turbine volume or power density as per the ‘751 patent. (SLTO = Sea Level Takeoff).

The Board ultimately found Knip rendered obvious the ‘751 patent because “it provided enough information to allow a skilled artisan to “determine a power density as defined in claim 1, and within the range proscribed in claim 1.” (Claim 3 was a dependent claim incorporating all limitation of claim 1; claim 16 depended on claim 15 which included the same argued limitations as claim 1).

The CAFC found that the PTAB erred by focusing on whether Knip enables a skilled artisan to calculate the power density of Knip’s contemplated “futuristic engine,” rather than considering “whether Knip enabled a skilled artisan to make and use the claimed invention.”

Specifically, “[i]n general, a prior art reference asserted under §103 does not necessarily have to enable its own disclosure, i.e., be ‘self-enabling,’ to be relevant to the obviousness inquiry.” That is, “a reference that does not provide an enabling disclosure for a particular claim limitation may nonetheless furnish the motivation to combine, and be combined with, another reference in which that limitation is enabled.” Thus, “[I]n the absence of such other supporting evidence to enable a skilled artisan to make the claimed invention, a standalone §103 reference must enable the portions of its disclosure being relied upon” This is “the same standard applied to anticipatory references.”

Here, the sole reference was Knip, and so the CAFC emphasized the question as being whether Knip enables the claimed invention not whether a skilled artisan “is provided with sufficient parameters in Knip to determine, without undue experimentation, a power density” as per the Boards focus. That CAFC noted that this position could have carried weight “if GE had presented other evidence to establish that a skilled artisan could have made the claimed turbofan engine with the recited power density. But no such other evidence was presented.”

Therefore, according to the CAFC, “Knip’s self-enablement (or lack thereof) is not only relevant to the enablement analysis, in this case it is dispositive.”

The CAFC discussed GE’s expert testimony finding it to be lacking, because its expert constructed “a computer model simulation of Knip’s imagined engine” rather than “suggesting that a skilled artisan could have actually built such an engine.” In contrast, Raytheon’s expert presented unrebutted evidence of non-enablement… detailing the unavailability of the revolutionary composite material contemplated by Knip.”

Lastly, GE had argued that a skilled artisan could achieve the claimed power density by optimizing Knip’s engine. The Board had affirmed this on the basis of “result-effective variable.” That CAFC rejected this, stating that “[i]f a skilled artisan cannot make Knip’s engine, a skilled artisan necessarily cannot optimize its power density.”

Accordingly, the CAFC reversed the PTAB’s finding.

Take-away:

- “[I]f an obviousness case is based on a non-self-enabled reference, and no other prior art reference or evidence would have enabled a skilled artisan to make the claimed invention, then the invention cannot be said to have been obvious.”

- If a single reference is used in a 103 rejection, and that single reference is non-self enabling, then allegations of optimization by the PTO is improper. That is, “if a skilled artisan cannot make..[it], a skilled artisan necessarily cannot optimize it…”

Who has Standing to Appeal of IPR Decision? And What is Teaching Away?

| April 21, 2021

General Electric Company v. Raytheon Technologies Corporation, No. 2019-1319.

Decided on December 23, 2020

Before Lourie, Reyna and Hughes (Opinion by Hughes).

Summary

Raytheon had ’920 patent which was related to a gas turbine engine. GE filed IPR and PTAB reviewed the claim and found the patent is non-obvious. GE filed a request for rehearing challenging the PTAB’s application of the legal standard for both teaching away and motivation to combine. The PTAB denied the request for rehearing and GE appealed to the CAFC. Raytheon claimed that GE does not have standing to appeal because GE did not have the injury in fact. At the appeal, GE showed a concrete business plan as evidence of injury in fact, and the CAFC found that GE has a substantial risk of future infringement and has standing. Then, the CAFC reviewed the PTAB’s decision on obviousness issue. Upon review, the CAFC found that the PTAB correctly set forth the standard for teaching away, however, applied it erroneously. The CAFC also found that the PTAB lacked substantial evidence for its conclusion that GE did not establish a motivation to combine the prior arts. Therefore, the CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision and remanded the case to the PTAB.

Details

Background

Raytheon Technologies Corporation (“Raytheon”[1]) filed US Patent No.8,695,920 (“’920 patent”) in 2011 and the patent was issued in April 2014.

In December 2016, General Electric Company (“GE”), a competitor of Raytheon in the industry of commercial aviation, petitioned to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) for reviewing the 920 patent’s claims 1-4, 7-14, and 19. GE explained that the claims were obvious based on two prior art references, Wendus and Moxon.

Before the IPR institution Raytheon disclaimed claims 1-4, 7, 8, 17, and 19. The PTAB reviewed only claims 9 -14. After the IPR institution, Raytheon disclaimed 9 and the PTAB only ruled on claims 10-14.

The disputed claims 10-14 were depended on independent claim 9.

9. A method of designing a gas turbine engine comprising:

providing a core nacelle defined about an engine centerline axis;

providing a fan nacelle mounted at least partially around said core nacelle to define a fan bypass flow path for a fan bypass air-flow;

providing a gear train within said core nacelle;

providing a first spool along said engine centerline axis within said core nacelle to

drive said gear train, said first spool includes a first turbine section including be-tween three–six (3–6) stages, and a first compressor section;

providing a second spool along said engine centerline axis within said core nacelle, said second spool includes a second turbine section including at least two (2) stages and a second compressor section;

providing a fan including a plurality of fan blades to be driven through the gear train by the first spool, wherein the bypass flow path is configured to provide a bypass ratio of airflow through the bypass flow path di-vided by airflow through the core nacelle that is greater than about six (6) during engine operation.

10. The method as recited in claim 9, wherein said first turbine section defines a pressure ratio that is greater than about five (5.0).

11. The method as recited in claim 10, wherein a fan pressure ratio across the plurality of fan blades is less than about 1.45.

12. The method as recited in claim 11, wherein the gear train is configured to provide a speed reduction ratio greater than about 2.5:1.

13. The method as recited in claim 12, wherein the plurality of fan blades are configured to rotate at a fan tip speed of less than about 1150 feet/second during engine operation.

14. The method as recited in claim 13, wherein the second turbine section includes two (2) stages.

The PTAB concluded that Wendus taught away from combination with Moxon and GE did not establish the obviousness of claim 10 when considered as a whole. Therefore, the PTAB found claims 10-14 are nonobvious. GE filed a request for rehearing challenging the PTAB’s application of the legal standard for both teaching away and motivation to combine. The PTAB denied the request for rehearing and GE timely appealed to the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”).

Standing

Raytheon moved to dismiss this appeal for lack of standing because GE has never “sued or threatened to sue” for infringing the ’920 patent. Raytheon also mentioned that GE “had never alleged that an engine exists that presents a concrete and substantial risk of infringing the ’920 patent,”

In JTEKT[2], the CAFC found that when the appellant does not currently engage in infringing activity and “relies on potential infringement liability as a basis for injury in fact”, the appellant must show that “it has concrete plans for future activity that creates a substantial risk of future infringement or would likely cause the patentee to assert a claim of infringement.”

In prior lawsuit between the same parties GE v. UTC[3], GE failed to show the evidence. However, the CAFC shows some guideline of what kind of evidence do we need to have a standing to appeal IPR decision to CAFC. GE responds that it has alleged facts that show it “is currently undertaking activities” likely to lead Raytheon to sue it for infringement.

Here, GE has shown concrete plans for future activities:

- GE spent $10–12 million in 2019 developing a geared turbofan architecture and design;

- GE intends to keep developing its geared turbofan engine design;

- The design is GE’s technologically preferred design for the next-generation narrow body market;

- GE has offered this preferred geared turbofan design to Airbus;

- GE has also established that such a sale would raise a substantial risk of an infringement suit; and

- GE believes its preferred design raises a substantial risk of infringement.

GE explicitly stated that “this preferred geared turbofan design includes a gear train driven by the low-pressure spool and a two-stage high-pressure turbine.” The CAFC found that this GE’s declaration “plausibly establish that its preferred next-generation engine design substantially risks infringing the ’920 patent.” With these concrete plans, the CAFC found that GE has shown concrete plans raising a substantial risk of future infringement.

Obviousness

The CAFC reviewed the PTAB’s decision on Obviousness. The patent at issue is related to “turbofan gas turbine engines used to propel commercial airliners.” Typically, a turbofan engine has four main components, (1) the fan, (2) compressor, (3) combustor, and (4) turbine[4]. In a turbofan engine, there are two ways airflow, “bypass flow” and “core flow.” The bypass ratio is a ratio of bypass flow to core flow and it was known that a “higher bypass ratio increases fuel efficiency.”

In the industry, the high-pressure compressor and high-pressure turbine are referred to as the “high spool” and the low-pressure compressor and low-pressure turbine are referred to as the “low spool.” Ordinary, “direct-drive” turbofan engine has a low spool and all connected to the same shaft and rotate at the same speed. On the other hand, a high bypass ratio (fuel-efficient) turbofan, the difference of the diameter of the fan and the engine creates the difference of the rotational speed and the rotational speed is ideal compared to the low-pressure turbine.

Contrary to the ordinary “low spool” turbofan, Raytheon’s patent was a “‘geared’ turbofan which uses a gearbox mounted between the low-pressure compressor and the fan to reduce the rotational speed of the fan compared to the” low spool turbine. When the gearbox is used, “the fan to rotate more slowly than the rest of the low spool.” Therefore, each part can rotate at an optimal speed and create many benefits. Such as reducing engine fuel consumption, improving aerodynamic efficiency with less costly design, reducing the mechanical stress on the fan and improving safety, reducing torque on the low spool shaft and allowing to design smaller diameter shaft, and reducing engine noise.

During the IPR, GE explained that “Wendus discloses all elements of claims 9–14 except that it teaches a one-stage high-pressure turbine instead of the “at-least-two-stage” high-pressure turbine taught in claim 9 and narrowed to two stages in claim 14” and “Moxon concludes that because of increased performance demands on the high-pressure turbine required to improve fuel efficiency, “a move to one instead of two high pressure turbine stages is thought unlikely, although designs have been carried out and demonstrations have been run.”

However, the PTAB found that Wendus taught away from combination with Moxon “despite the PTAB’s prior findings of the benefits of the two-stage high-pressure turbine” and concluded “GE did “not establish the obviousness of claim 10 when considered as a whole.” Therefore, the PTAB found claims 10-14 are nonobvious.

Therefore, GE pointed the errors of the Board’s decision on three issues before the CAFC. As to the first issue, teaching away, GE asserted that “the PTAB errored by misreading Wendus to find that it disparages or discourages the use of a two-stage high pressure turbine, and therefore erred in finding that Wendus taught away from a two-stage high-pressure turbine.” For the second issue, artisan’s motivation to combine references, GE also argues that the PTAB “applied an overly rigorous requirement for motivation to combine the Wendus and Moxon references.” Lastly, GE argues that the PTAB also erred by requiring GE to show that an artisan would be motivated to retain the claimed performance parameters taught in Wendus in combining Wendus and Moxon.

Raytheon counter-argued that the CAFC must affirm the PTAB’s decision if there is substantial evidence of “(1) Wendus teaches away from modifying its advanced engine to add a two-stage high-pressure turbine; (2) no matter if Wendus teaches away, Wendus discloses a strong preference for a one-stage high-pressure turbine, undermining GE’s motivation-to-combine arguments; or (3) GE failed to establish a motivation for modifying the Wendus advanced engine to achieve the invention of claim 10, ‘as a whole.’”

CAFC stated that the PTAB correctly set forth the standard for teaching away.

“[a] reference does not teach away ‘if it merely expresses a general preference for an alternative invention but does not “criticize, discredit, or otherwise discourage” investigation into the invention claimed.’”

The PTAB found that criticism of the use of a two-stage high-pressure turbine in the prior art suggests a general preference for a one-stage high-pressure turbine.

By referencing Table 16 of Wendus[5], the PTAB concluded that “Wendus discourages the useof a two-stage high-pressure turbine rather than merely suggesting a general preference for a one-stage high-pressure turbine because…A person of ordinary skill in the art would have known that modifying the Wendus [advanced] engine to include a two-stage turbine would have increased the weight and cost of the engine which Wendus criticizes, discredits, or otherwise discourages.”

However, the CAFC found that the PTAB misleads Table 16 in the full context of Wendus because “Wendus itself only weakly supports that a one-stage high-pressure turbine has weight and cost advantages over a two-stage high pressure turbine.” Also, the CAFC mentioned that “Wendus itself does not criticize the use of a two-stage turbine for weight or cost reasons” and “Wendus references neither efficiency nor number of parts in comparison to any other high-pressure turbine design.”

The CAFC also explained that “even if an artisan recognized that a one-stage turbine would have led to reduced engine weight and lower engine cost than a two-stage turbine, Wendus is hardly consistent in indicating that weight and cost concerns alone mandate the correct design choices of an improved engine, compared to other factors like fuel efficiency or reliability.”

“Wendus ‘expressly weigh[ed] the tradeoffs [between a one-stage and two-stage turbine] and cho[se] the one-stage option’ cannot withstand scrutiny.” Therefore, the CAFC conclude that “Wendus does not criticize, credit, or discourage the use of a two-stage high-pressure turbine” and there is no substantial evidence to support the PTAB’s conclusion of teaching away.

Secondly, the CAFC concluded that the PTAB lacks substantial evidence for its conclusion that GE did not establish a motivation to combine Wendus and Moxon. By referring the PharmaStem Therapeutics[6], the CAFC confirmed the standard of obviousness is that “a person of ordinary skill in the art would have had reason to attempt to make the composition or device, or carry out the claimed process, and would have had a reasonable expectation of success in doing so.”

The CAFC found that the PTAB again misread Wendus and applied “its faulty findings that Wendus described ‘the one-stage turbine as a critical and enabling technology providing significant advantages over a prior art engine having a two-stage turbine,’ and that ‘other [Wendus] engine components [being] specifically designed to accommodate the [one-stage] turbine[7].”

Finally, the CAFC concluded that the PTAB’s holding that GE did not establish the obviousness of claim 10 “as a whole” lacks substantial evidence. The CAFC pointed that “Wendus meets all the elements of claim 10 except for the two-stage high-pressure turbine, which Moxon discloses” and “GE does not merely identify each claim element as present in Wendus and Moxon. Instead, GE’s obviousness theory combines the elements disclosed in Wendus’s advanced engine with Moxon’s teaching of a two-stage high-pressure turbine to attain better turbine reliability and efficiency.”

Therefore, the CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision and remand the case to the PTAB.

Takeaway

- As to the standing requirement “injury in fact”, this case shows what degree the appellee needs to prove the concrete plans in the future and what type of evidence is appropriate. 35 U.S.C §319 states that “Any party to the inter partes review shall have the right to be a party to the appeal.” The law did not specifically state the minimum standing requirement to appeal of IPR decision.

- An appellant’s declaration that it believes the preferred design raises a substantial risk of infringement is also plausible only if the declaration was supported by the other evidence.

- When determining the obviousness by teaching away from the prior art references, the meaning must be interpreted by the entire reference, not the partial words in the reference.

- Teaching away argument needs “criticize” more than “preference.”

[1] During the appeal, Raytheon was known as United Technologies Corporation.

[2] JTEKT Corp. v. GKN Auto. LTD., 898 F.3d 1217, 1221 (Fed. Cir. 2018), cert. denied, 139 S. Ct. 2713 (2019).

[3] Gen. Elec. Co. v. United Techs. Corp., 928 F.3d 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

[4] The compressor pressurized the air come into the core flow. Then, the combustor mixed the compressed air and fuel and ignite and generates hot gas. The hot gas expands in the turbine and create power to rotate the blades in turbine.

[5] Wendus, See page 52 of https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20030067946/downloads/20030067946.pdf

[6] PharmaStem Therapeutics, Inc. v. ViaCell, Inc., 491 F.3d 1342, 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

[7] Final Written Decision at *13 (citations omitted).

New evidence submitted with a reply in IPR institution proceedings

| December 30, 2020

VidStream LLC v. Twitter, Inc.

November 25, 2020

Newman, O’Malley, and Taranto. Court opinion by Newman.

Summary

On appeals from the United States Patent and Trademark Office in IPR arising from two petitions filed by Twitter, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s ruling that Bradford is prior art (printed publication) against the ’997 patent where the priority date of the ’997 patent is May 9, 2012 and a page of the copy of Bradford cited in Twitter’s petitions stated, in relevant parts, “Copyright © 2011 by Anselm Bradford and Paul Haine” and “Made in the USA Middletown, DE 13 December 2015.” The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s admission of new evidence regarding Bradford submitted by Twitter in reply (not included in petitions). The Federal Circuit also affirmed the Board’s rulings of unpatentability of claims 1– 35 of the ’997 patent over Bradford and other prior art references, in the two IPR decisions on appeal.

Details

I. background

U.S. Patent No. 9,083,997 (“the ’997 patent”), assigned to VidStream LLC, is directed to “Recording and Publishing Content on Social Media Websites.” The priority date of the ’997 patent is May 9, 2012.

Twitter filed two petitions for inter partes review (“IPR”), with method claims 1–19 of the ’997 patent in one petition, and medium and system claims 20–35 of the ’997 patent in the other petition. Twitter cited Bradford as the primary reference for both petitions, combined with other references.

With the petitions, Twitter filed copies of several pages of the Bradford book, and explained their relevance to the ’997 claims. Twitter also filed a Bradford copyright page that contains the following legend:

Copyright © 2011 by Anselm Bradford and Paul Haine

ISBN-13 (pbk): 978-1-4302-3861-4

ISBN-13 (electronic): 978-1-4302-3862-1

A page of the copy of Bradford cited in Twitter’s petitions also states:

Made in the USA

Middletown, DE

13 December 2015

VidStream, in its patent owner’s response, argued that Bradford is not an available reference because it was published December 13, 2015.

Twitter filed replies with additional documents, including (i) a copy of Bradford that was obtained from the Library of Congress, marked “Copyright © 2011” (this copy did not contain the “Made in the USA Middletown, DE 13 December 2015” legend); and (ii) a copy of Bradford’s Certificate of Registration that was obtained from the Copyright Office and contains following statements:

Effective date of registration: January 18, 2012

Date of 1st Publication: November 8, 2011

“This Certificate issued under the seal of the Copyright Office in accordance with title 17, United States Code, attests that registration has been made for the work identified below. The information on this certificate has been made a part of the Copyright Office records.”

Twitter also filed following declarations:

The Declaration of “an expert on library cataloging and classification,” Dr. Ingrid Hsieh-Yee, who declared that Bradford was available at the Library of Congress in 2011 with citing a Machine-Readable Cataloging (“MARC”) record that was created on August 25, 2011 by the book vendor, Baker & Taylor Incorporated Technical Services & Product Development, adopted by George Mason University, and modified by the Library of Congress on December 4, 2011.

the Declaration of attorney Raghan Bajaj, who stated that he compared the pages from the copy of Bradford submitted with the petitions, and the pages from the Library of Congress copy of Bradford, and that they are identical.

Twitter further filed copies of archived webpages from the Internet Archive, showing the Bradford book listed on a publicly accessible website (http://www.html5mastery.com/) bearing the website date November 28, 2011, and website pages dated December 6, 2011 showing the Bradford book available for purchase from Amazon in both an electronic Kindle Edition and in paperback.

VidStream filed a sur-reply challenging the timeliness and the probative value of the supplemental information submitted by Twitter.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB” or “Board”) instituted the IPR petitions, found that Bradford was an available reference, and held claims 1–35 unpatentable in light of Bradford in combination with other cited references. Regarding Bradford, the Board discussed all the materials that were submitted, and found:

“Although no one piece of evidence definitively establishes Bradford’s public accessibility prior to May 9, 2012, we find that the evidence, viewed as a whole, sufficiently does so. In particular, we find the following evidence supports this finding: (1) Bradford’s front matter, including its copyright date and indicia that it was published by an established publisher (Exs. 1010, 1042, 2004); (2) the copyright registration for Bradford (Exs. 1015, 1041); (3) the archived Amazon webpage showing Bradford could be purchased on that website in December 2011 (Ex. 1016); and (4) Dr. Hsieh-Yee’s testimony showing creation and modification of MARC records for Bradford in 2011.”

VidStream timely appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed all aspects of the Board’s holdings including Bradford being prior art (printed publication).

The critical issue on this appeal is whether Bradford was made available to the public before May 9, 2012, the priority date of the ’997 patent.

Admissibility of Evidence – PTAB Rules and Procedure

VidStream argued that Twitter was required to include with its petitions all the evidence on which it relies because the PTO’s Trial Guide for inter partes review requires that “[P]etitioner’s case-in-chief” must be made in the petition, and “Petitioner may not submit new evidence or argument in reply that it could have presented earlier.” Trial Practice Guide Update, United States Patent and Trademark Office 14–15 (Aug. 2018), https://www.uspto.gov/sites/de- fault/files/documents/2018_Revised_Trial_Practice_Guide. pdf.

Twitter responded that the information filed with its replies was appropriate in view of VidStream’s challenge to Bradford’s publication date, and that this practice is permitted by the PTAB rules and by precedent, which states: “[T]he petitioner in an inter partes review proceeding may introduce new evidence after the petition stage if the evidence is a legitimate reply to evidence introduced by the patent owner, or if it is used to document the knowledge that skilled artisans would bring to bear in reading the prior art identified as producing obviousness.” Anacor Pharm., Inc. v. Iancu, 889 F.3d 1372, 1380–81 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

The Federal Circuit sided with Twitter, concluding that the Board acted appropriately, for the Board permitted both sides to provide evidence concerning the reference date of the Bradford book, in pursuit of the correct answer.

The Bradford Publication Date

VidStream argued that, even if Twitter’s evidence submitted in reply were considered, the Board did not link the 2015 copy of Bradford with the evidence purporting to show publication in 2011, i.e., the date of copyright registration, the archival dates for the Amazon and other webpages, and the date the MARC records were created. VidStream argued that the Board did not “scrutiniz[e] whether those documents actually demonstrated that any version of Bradford was publicly accessible at that time.” VidStream states that Twitter did not meet its burden of showing that Bradford was accessible prior art.

Twitter responded that that the evidence established the identity of the pages of Bradford filed with the petitions and the pages from the copy of Bradford in the Library of Congress. Twitter explains that the copy “made” on December 13, 2015 was a reprint, for the 2015 copy has the same ISBN as the Library of Congress copy, as is consistent with a reprint, not a new edition.

After citing arguments of both parties, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s ruling that Bradford is prior art against the ’997 patent because “[t]he evidence well supports the Board’s finding that Bradford was published and publicly accessible before the ’997 patent’s 2012 priority date.” There is no more explanation than this for the affirmance.

Obviousness Based on Bradford

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s rulings of unpatentability of claims 1– 35 of the ’997 patent, in the two IPR decisions on appeal because VidStream did not challenge the Board’s decision of obviousness if Bradford is available as a reference.

Takeaway

· Although all relevant evidence should be submitted with an IPR petition, new evidence submitted with a reply may have chance to be admitted if the new evidence is a legitimate reply to the evidence introduced by a patent owner, or if it is used to document the knowledge that skilled artisans would bring to bear in reading the prior art identified as producing obviousness.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board has discretion in issuing sanctions and is not limited by the Sanctions Regulations under Rule 42.12

| November 5, 2020

APPLE INC. v. VOIP-PAL.COM, INC.

September 25, 2020

Prost, Reyna and Hughes. Opinion by Reyna.

Summary:

After being sued by Voip-Pal, Apple filed separate IPR petitions against the two patents asserted against Apple. During the IPRs, Voip-Pal sent letters to PTAB judges and the USPTO, among others, criticizing the IPR process and requesting either dismissal of the IPRs or favorable judgment. These letters were not sent to Apple. The PTAB issued a final written decision upholding the validity of the claims. Apple then filed a motion for sanctions due to the ex parte communications. The PTAB held that the letters sent by Voip-Pal were sanctionable and the remedy was to provide a new PTAB panel to review Apple’s request for rehearing. On appeal at the CAFC, but before the oral arguments, a separate CAFC decision issued affirming the invalidity of some of the same claims from the same patents. The CAFC stated that for the same claims involved in the prior case, the claims are invalid, and thus, the appeal is moot. However, for the claims that do not overlap with the claims involved in the prior case, the appeal is not moot. Regarding sanctions, the CAFC stated that the PTAB did not abuse its discretion in the remedy provided to Apple. The CAFC also affirmed the PTAB’s determination of non-obviousness.

Details:

Voip-Pal sued Apple for infringement of U.S. Patent Nos. 8,542,815 and 9,179,005 to Producing Routing Messages for Voice Over IP Communications. The patents describe routing communications between two different types of networks. Apple filed two separate IPR petitions for the patents. Apple agued that the patents were obvious over the combination of U.S. Patent No. 7,486,684 (Chu ‘684) and U.S. Patent No. 8,036,366 (Chu ‘366). The original PTAB panel instituted the IPRs. Later the original PTAB panel was replaced with a second PTAB panel. No reason for the change in panels was provided in the record.

While the IPRs were proceeding, the CEO of Voip-Pal sent six letters to various parties copying members of Congress, the President, federal judges, and administrative patent judges at the PTAB. The letters were not sent to Apple. The letters criticized the IPR system and requested judgment in Voip-Pal’s favor or dismissal of Apple’s IPRs.

The second PTAB panel then issued its final written decision for both IPRs. The claims were found to be not invalid as obvious over Chu ‘684 and Chu ‘366. Specifically, the PTAB said that Apple did not provide evidentiary support for their argument on motivation to combine.

Apple moved for sanctions against Voip-Pal due to the CEO’s ex parte communications with the PTAB and the USPTO arguing that the communications violated the Administrative Procedure Act and violated Apple’s due process rights. Apple requested an adverse judgment against Voip-Pal or that the final written decision be vacated and assigned to a new panel with a new proceeding. Apple also appealed the final written decision by the second PTAB panel.

The CAFC stayed the appeal and remanded to the PTAB to consider Apple’s sanctions motions. A third and final PTAB panel replaced the second PTAB panel for the sanctions proceedings. The final PTAB panel found that Voip-Pal’s ex parte communications were sanctionable. But the final PTAB panel rejected Apple’s request for a directed judgment or a new proceeding with a new panel. The final PTAB panel provided their own sanctions remedy of presiding over Apple’s request for rehearing. The final PTAB panel stated that this “achieves the most appropriate balance when considering both parties’ conduct as a whole.”

After briefing for the rehearing, the final PTAB panel denied Apple’s petition for rehearing because Apple had “not met its burden to show that in the Final Written Decision, the [Interim] panel misapprehended or overlooked any matter.” The final PTAB panel also stated that “even if [the final PTAB panel] were to accept [Apple’s] view of Chu ‘684 … [the final PTAB panel] would not reach a different conclusion.” The CAFC then lifted the stay on the appeal.

Prior to oral argument at the CAFC, Apple filed a post-briefing document entitled “Suggestion of Mootness.” Apple raised the issue of mootness because in a separate proceeding involving the same patents (Voip-Pal.com, Inc. v. Twitter, Inc., 798 F. App’x 644 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the CAFC affirmed that some of the claims of the patents are invalid as ineligible subject matter.

At the oral argument, Apple argued that the appeals for the overlapping claims are moot. Voip-Pal did not dispute mootness of the appeals for the overlapping claims. Since these claims were rendered invalid as ineligible subject matter in the Twitter case, the CAFC stated that appeals for these claims are rendered moot. For the remaining, 15 non-overlapping claims, Apple argued that they are essentially the same as the claims held ineligible in the Twitter case and that “basic principles of claim preclusion (res judicata) preclude Voip-Pal from accusing Apple” of infringing the non-overlapping claims in future litigation.

The CAFC stated that:

Under the doctrine of claim preclusion, “a judgment on the merits in a prior suit involving the same parties or their privies bars a second suit based on the same cause of action.” Lawlor v. Nat’l Screen Serv. Corp., 349 U.S. 322, 326 (1955). The determination of the “precise effect of the judgment[] in th[e] [first] case will necessarily have to be decided in any such later actions that may be brought.” In re Katz Interactive Call Processing Pat. Litig., 639 F.3d 1303, 1310 n.5 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

Thus, any res judicata effect of a first proceeding is “an issue that only a future court can resolve” and any preclusive effect that the Twitter case could have against the same or other parties must be decided in any subsequent action brought by Voip-Pal. The CAFC concluded that the question of obviousness for the non-overlapping claims is not moot.

Regarding the sanctions order, the CAFC stated that the final PTAB panel’s sanction order was not an abuse of discretion. Apple argued that the final PTAB panel’s sanction order violated the administrative procedure act (“APA”) because the PTAB panel issued a sanction not explicitly provided by 37 C.F.R. § 42.12(b), and thus, the PTAB panel exceeded its authority. However, the CAFC pointed out that § 42.12 provides that:

(a) The Board may impose a sanction against a party for misconduct, . . . .

(b) Sanctions include entry of one or more of the following [eight enumerated sanctions]:

The CAFC stated that because of the term “include,” the list of sanctions is non-exhaustive. The use of “may” in the rule also indicates that the PTAB has discretion to impose sanctions in the first place. Therefore, the PTAB is not limited to the eight listed sanctions in § 42.12(b). The CAFC also stated that the PTAB’s decision to allow Apple to petition for rehearing before a new panel was a reasonable course of action that provided Apple with a meaningful opportunity to respond to Voip-Pal’s letters.

Regarding Apple’s due process argument, the CAFC stated that Apple failed to identify any property interests in the course of its due process arguments, and that property interests identified for the first time on appeal are waived. An argument of a due process violation requires identification of a property interest that has been deprived. The CAFC also stated that the PTAB introduced the six letters into the record and gave Apple an opportunity to respond during the panel rehearing stage, but Apple chose not to address the substance of the letters.

Apple also argued that the PTAB erred when it determined that Apple failed to establish a motivation to combine Chu ‘684 with Chu ‘366 stating that the PTAB improperly applied the old teaching, suggestion, motivation test rather than the flexible obviousness analysis required under KSR. However, the CAFC stated that Apple’s argument was that a skilled artisan would have viewed Chu ‘684’s interface as less intuitive and less user friendly than that of Chu ‘366, and thus, a skilled artisan would have a desire to improve Chu ‘684’s system. But the PTAB determined that Apple’s expert did not provide adequate support for the proposition that a skilled artisan would have regarded Chu ‘684’s teachings as deficient. Thus, Apple failed to “articulate reasoning with some rational underpinning.” The CAFC stated that the PTAB applied the proper evidentiary standard in determining non-obviousness of the claims.

Comments

This decision shows that the PTAB has discretion in issuing sanctions and they are not limited to the list enumerated in 37 C.F.R. § 42.12. Also, issue preclusion can only be applied to a future action. The effect of a judgment in a first case must be decided in any later actions that may be brought. For demonstrating obviousness, make sure you include evidentiary support for an argument of obviousness.

Same difference: A broad interpretation of “contrast” renders patented design obvious in view of prior art showing a similar “level of contrast”.

| October 19, 2020

Sealy Technology, LLC v. SSB Manufacturing Company (non-precedential)

August 26, 2020

Before Prost, Reyna, and Hughes (Opinion by Prost).

Summary

In nixing a design patent purporting to show “contrast” between design elements, the Federal Circuit broadly interprets “contrast” in the claimed design as not requiring a level of contrast that is different than what is available in the prior art.

Details

In their briefs to the Federal Circuit, Sealy Technology, LLC (“Sealy”) told the story about how, during a slump in sales around 2009, they re-designed their Stearns & Foster luxury-brand mattresses to visually distinguish their mattresses in a marketplace overrun with white or otherwise monochromatic mattress designs.

To be visually distinct, Sealy incorporated a “bold” combination of contrast edging running horizontally along the edges of the mattress and around the handles on the mattress.

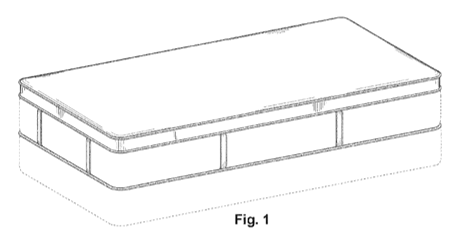

Sealy claimed this design in their U.S. Design Patent No. 622,531 (“D531 patent”). The D531 patent claimed “[t]he ornamental design for a Euro-top mattress design, as shown and described”, with Figure 1 being representative:

The D531 patent did not contain any textual descriptions of the contrast edging in Sealy’s mattress design.

Sealy’s dispute with Simmons Bedding Company (“Simmons”) began shortly after the D531 patent issued, when in 2010, Sealy sued Simmons for infringing the D531 patent. The product at issue was Simmons’s Beautyrest-brand mattress:

in 2011, Simmons sought an inter partes reexamination of the D531 patent. During the first round of the reexamination, the Examiner interpreted the claimed design as including the following elements:

- The horizontal piping along the edges of the top and bottom of the mattress and along the top flat surface of the pillow top layer has a contrasting appearance.

- The [eight] flat vertical handles each have contrasting sides of edges running vertically with the length of the handles.

However, the Examiner declined to adopt any of Simmons’s requested anticipation and obviousness challenges. And when Simmons appealed the Examiner’s refusal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, Sealy vouched for the Examiner’s interpretation.

Unfortunately for Sealy, the Board on appeal entered new obviousness rejections. A second round of the reexamination followed. This time around, the Examiner adopted the Board’s rejections, which Sealy was unable to overcome even after a second appeal to the Board. Sealy then appealed the rejections to the Federal Circuit.

Sealy raised two main issues on appeal: first, whether the Board correctly construed the “contrast” in the claimed design; and second, whether the cited prior art was a proper primary reference.

On the question of claim construction, the Board had determined that “the only contrast necessary is one of differing appearance from the rest of the mattress”, whether by contrasting fabric, contrasting color, contrasting pattern, and contrasting texture.

Sealy argued that the Board’s construction was too broad. The proper construction, argued Sealy, should require a more specific level of contrast, that is, “a contrasting value and/or color” or “something that causes the edge to stand out or to be strikingly different and distinct from the rest of the design”.

Sealy relied on MPEP 1503.02(II), which provides that “contrast in materials may be shown by using line shading in one area and stippling in another”, that “the claim will broadly cover contrasting surfaces unlimited by color”, and that “the claim would not be limited to specific material”. Sealy also argued that a designer of ordinary skill in the art would have understood the D531 patent as requiring a more specific degree of contrast than the Board’s construction.

The Federal Circuit disagreed.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Examiner and the Board’s findings that the patent contained no textual descriptions about contrast in the claimed design, that the drawings did not convey a different level of contrast than the prior art, and that Sealy’s argument regarding the understanding of a designer skilled in the art lacked evidentiary support..

On the question of obviousness, Sealy challenged the Board’s reliance on the Aireloom Heritage mattress shown below, arguing that the prior art mattress lacked the requisite contrast.

The weakness in Sealy’s argument was that its success depended entirely on the Federal Circuit adopting Sealy’s claim construction. And because the Federal Circuit did not find that the claimed design required a “strikingly different” contrast between the edging and the rest of the mattress, the Federal Circuit agreed with the Board’s determination that the prior art mattress had “at least some difference in appearance” between the edging and the rest of the mattress. This was sufficient to qualify the Aireloom Heritage mattress as a proper primary reference.

Takeaway

- Consider adding strategic textual descriptions in the specification to clarify the claimed design. For example, in Sealy’s case, since the contrast in the claimed design is provided in part by contrast in color, it may have been helpful to include such descriptions as “Figure 1 is a perspective view of a mattress showing a first embodiment f the Euro-top mattress design with portions shown in stippling to indicate color contrast”.

- If color contrast is important to the claimed design, consider adding solid black shading to the appropriate portions. 37 C.F.R. 1.152 (“Solid black surface shading is not permitted except when used to represent the color black as well as color contrast”).

- If the color scheme is important to the claimed design, consider filing a color drawing with the design application. One of Apple’s design patents on the iPhone graphical user interface includes a color drawing, which helped Apple’s infringement case against Samsung because similarities between the claimed design and the graphical user interface on Samsung’s Galaxy phones were immediately noticeable.

LICENSING AGREEMENTS AND TESTIMONIES COULD BE USED AS EVIDENCE OF SECONDARY CONSIDERATIONS TO OVERCOME OBVIOUSNESS ONLY WHEN THEY PROVIDE A “NEXUS” TO THE PATENTS

| October 10, 2020

Siemens Mobility, Inc. v. U.S. PTO

September 8, 2020

Lourie (author), Moore, and O’Malley

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s final decision that claims of Siemens’s patents are unpatentable as obvious. The Federal Circuit found that the PTAB’s findings in claim construction of “corresponding regulations,” and evaluation of Siemens’s evidence of secondary considerations are clearly supported by substantial evidence.

Details:

Siemens Mobility, Inc. (“Siemens”) appeals from two final decisions of the PTAB, where the PTAB held that claims 1-9 and 11-19 of U.S. Patent No. 6,609,049 (“the ‘049 patent) and claims 1-9 and 11-19 of U.S. Patent No. 6,824,110 (“the ‘110 patent) were unpatentable.

The ‘049 patent and ‘110 patent

Siemens’s ‘049 and ‘110 patents are directed to methods and systems for automatically activating a train warning device, including a horn, at various locations. The systems include a control unit, a GPS receiver, and database of locations of grade crossings, and a horn. Siemens’s two patent disclose that if that grade crossing is subject to state regulations, the horn is activated based on those state regulations. If that grade crossing is not subject to state regulations, Siemens’s system considers that crossing as subject to a Federal Railroad Administration regulation and sounds the horn when the train is 24 seconds or fewer away from the crossing.

Independent claim 1 of ‘110 patent:

1. A computerized method for activating a warning device on a train at a location comprising the steps of:

maintaining a database of locations at which the warning device must be activated

and corresponding regulations concerning activation of the warning device;

obtaining a position of the train from a positioning system;

selecting a next upcoming location from among the locations in the database based at least in part on the position;

determining a point at which to activate the warning device in compliance with a

regulation corresponding to the next upcoming location; and

activating the warning device at the point.

The claims of the ‘049 and ‘110 patents substantially similar.

PTAB

Westinghouse Air Brake Technologies Corporation (“Westinghouse”) petitioned for IPR, challenging claims of both ‘049 and ‘110 patents under §103.

The PTAB found that all challenged claims would have been obvious over two references (Byers and Michalek). In addition, the PTAB did not found Siemens’s evidence of secondary considerations to be persuasive. Finally, the PTAB found that a skilled artisan would have combined the teachings of both references.

Siemens appealed.

CAFC

Three aspects of the PTAB decisions at issue in the appeal:

- The board’s claim construction of “corresponding regulations”;

- The board’s evaluation of Siemens’s evidence of secondary considerations; and

- The board’s findings of a person of skill in the art would have combined both references.

As for the second issue, Siemens presented two license agreements to both patents. Also, Siemens provided evidence regarding Westinghouse’s request to license and testimony from Westinghouse employees regarding the strength of two patents.

Siemens argued that the PTAB improperly discounted this evidence for lack of nexus.

The CAFC did not find those license agreements to be persuasive.

The CAFC noted that the license agreement with Norfolk Southern was presented to the PTAB with royalty information redacted and that another license was provided only for a nominal fee. Also, the CAFC noted that a license request from Westinghouse was for avoiding the cost of a pending patent infringement suit.

Furthermore, the CAFC agreed with the PTAB’s position that testimony from Westinghouse “provided a scant basis for accessing the value of the ‘110 patent” because while the testimony referred to a “horn sequencing patent” or “automatic horn activation,” it did not provide any connection to the language of the claims.

Therefore, the CAFC held that the PTAB’s findings were clearly supported by substantial evidence.

Takeaway:

- In the obviousness analysis, a nexus is required between the merits of the claimed invention and the offered evidence.

- Licensing agreements and testimonies could be used as evidence of secondary considerations to overcome obviousness only when they provide a “nexus” to the patents at issue.

Tags: employee testimony > evidence of secondary considerations > licensing agreement > nexus > obviousness

PTAB Should Provide Adequate Reasoning and Evidence in Its Decision and Teaching Away Argument Requires More Than a General Preference

| August 26, 2020

ALACRITECH, INC. V. INTEL CORP., CAVIUM, LLC, DELL, INC.

July 31, 2020

Before Stoll, Chen, and Moore

Summary

The Federal Circuit reviewed the adequacy of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s (Board) obviousness findings under the Administrative Procedure Act’s (APA) requirement that the Board’s decisions be supported by adequate reasoning and evidence. The Federal Circuit agreed with Alacritech’s argument that the Board did not adequately support the finding. The Federal Circuit found no reversible error in the Board’s remaining obviousness determination. The Federal Circuit vacated in part and remanded the Board’s decision.

Background

Alacritech, Inc. owns the patent 8,131,880. Intel Corp., et al., (Intel) petitioned to the Board for inter partes review (IPR) of the patent ‘880. The Board’s final decisions found the challenged claims unpatentable as obvious. Alacritech appealed the Board’s obviousness decision for four independent claims.

The ‘880 patent relates to computer networking and is directed to a network-related apparatus and method for offloading certain network processing from a central processing unit (CPU) to an “intelligent network interface card.” Intel asserted that the challenged claims would have been obvious over Thia1 in view of Tanenbaum2. The Board agreed and held all of the challenged claims unpatentable as obvious in the final written decisions. On appeal in the Federal Circuit, one of the focus was on claim 41 reciting “a flow re-assembler disposed in the network interface” as follows:

| 41. An apparatus for transferring a packet to a host computer system, comprising: a traffic classifier, disposed in a network interface for the host computer system, configured to classify a first packet received from a network by a communication flow that includes said first packet; a packet memory, disposed in the network interface, configured to store said first packet; a packet batching module, disposed in the network interface, configured to determine whether another packet in said packet memory belongs to said communication flow; a flow re-assembler, disposed in the network interface, configured to re-assemble a data portion of said first packet with a data portion of a second packet in said communication flow; and a processor, disposed in the network interface, that maintains a TCP connection for the communication flow, the TCP connection stored as a control block on the network interface. |

Discussion

Alacritech argued that the Board’s analysis was inadequate to support its findings on claims 41-43. Independent claim 43 is similar to claim 41, but recites a limitation in the network interface with “a re-assembler for storing data portions of said multiple packets without header portions in a first portion of said memory.” The dispute was focused on where reassembly takes place in the prior art and whether that location satisfies the claim limitations. The alleged claims incorporate limitations that require reassembly in the network interface, as opposed to a central processor. Intel argued that “Thia . . . discloses a flow re-assembler on the network interface to re-assemble data portions of packets within a communication flow.” In response, Alacritech argued that “[n]either Thia nor Tanenbaum discloses a flow re-assembler that is part of the NIC.”

The Board recited some of the parties’ arguments and concluded that the asserted prior art teaches the reassembly limitations. Alacritech argued that the Board’s analysis did not adequately support its obviousness finding. The Federal Circuit reviewed the adequacy of the Board’s obviousness finding under the APA’s requirement that the Board’s decisions be supported by adequate reasoning and evidence. The Federal Circuit emphasized that the Board’s findings need not be perfect, but must be “reasonably discernable.” However, the Board failed to meet the requirement by explaining why it found those arguments persuasive. The Federal Circuit reasoned that the Board briefly recites two terse paragraphs from the parties’ arguments and, in doing so, “appears to misapprehend both the scope of the claims and the parties’ arguments.” Further, the Federal Circuit turned down Intel’s argument that it should prevail because the Board “soundly rejected” Alacritech’s arguments. But the Board’s rejection does not necessarily support the Board’s finding that the asserted prior art teaches or suggests reassembly in the network interface. The Board should meet the obligation to “articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action including a rational connection between the facts found and the choice made.” The Federal Circuit, therefore, vacated the portion of the Board’s decision.

Alacritech successfully kept the ball rolling due to the Board’s inadequate reasoning and evidence. However, Alacritech did not substantially weaken the obviousness determination, and its teaching away argument on Tanenbaum hit the wall. Tanenbaum suggests on protocols for gigabit networks that “[u]sually, the best approach is to make the protocols simple and have the main CPU do the work.” Such a statement did not disparage other approaches. As pointed out by the Federal Court, “Tanenbaum merely expresses a preference and does not teach away from offloading processing from the CPU to a separate processor.”

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s finding of a motivation to combine Thia and Tanenbaum, explaining that “[a] reference that ‘merely expresses a general preference for an alternative invention but does not criticize, discredit, or otherwise discourage investigation into’ the claimed invention does not teach away.” (Meiresonne v. Google (Fed. Cir. March 7, 2017)) The proposition makes clear that a general preference cannot support teaching away argument. A proper teach away argument requires evidence that shows the prior art references would lead away from the claimed invention.

Takeaway

- The PTAB’s obviousness findings should meet the APA’s requirements to support its decisions with adequate reasoning and evidence.

- A proper teach away argument requires evidence that shows the prior art references would lead away from the claimed invention.

CAFC Finds Claim Limitations Missing in the Prior Art May Still Be Obvious with Common Sense

| July 13, 2020

B/E AEROSPACE, INC. v. C&D ZODIAC, INC

June 26, 2020

Lourie, Reyna, and Hughes, Opinion by Reyna.

Summary:

On appeal from an inter partes review proceeding wherein the petitioner, C&D Zodiac, Inc. (“Zodiac”), successfully challenged two patents owned by B/E Aerospace, Inc. (“B/E”), U.S. Patent No. 9,073,641 (“the ’641 patent”) and U.S. Patent No. 9,440,742 (“the ’742 patent”) B/E asserted that the PTAB had failed to consider all the limitations of the claims. The patents involved space-saving technologies for aircraft enclosures, such as lavatory enclosures, designed to “reduce or eliminate the gaps and volumes of space required between lavatory enclosures and adjacent structures.”

The CAFC concluded that the Board’s final determination of obviousness by predictable result of a known element and common sense was correct and therefore affirmed the Board’s decision.

Details:

Claim 1 of the ’641 patent was designated as representative of the challenged claims.

1. An aircraft lavatory for a cabin of an aircraft of a type that includes a forward-facing passenger seat that includes an upwardly and aftwardly inclined seat back and an aft-extending seat support disposed below the seat back, the lavatory comprising:

a lavatory unit including a forward wall portion and defining an enclosed interior lavatory space, said forward wall portion configured to be disposed proximate to and aft of the passenger seat and including an exterior surface having a shape that is substantially not flat in a vertical plane; and

wherein said forward wall portion is shaped to substantially conform to the shape of the upwardly and aftwardly inclined seat back of the passenger seat, and includes a first recess configured to receive at least a portion of the upwardly and aftwardly inclined seat back of the passenger seat therein, and further includes a second recess configured to receive at least a portion of the aft-extending seat support therein when at least a portion of the upwardly and aftwardly inclined seat back of the passenger seat is received within the first recess.

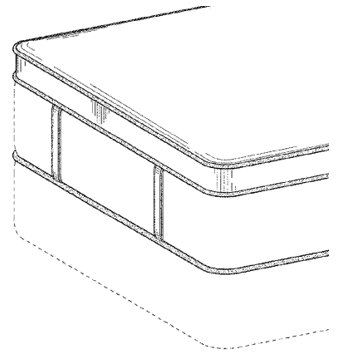

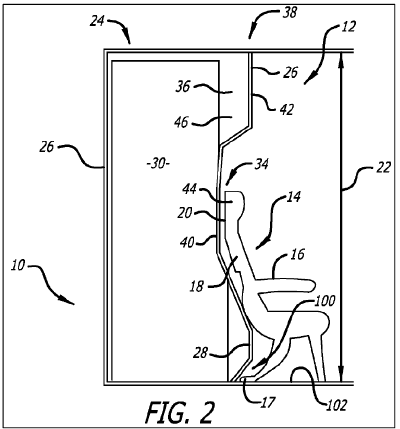

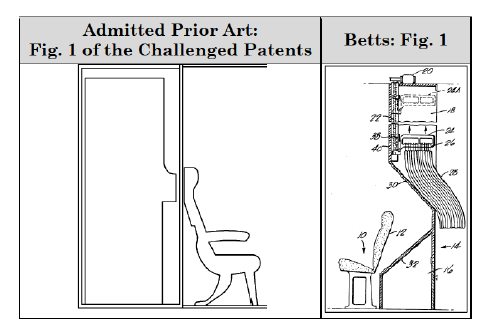

The appeal focused on the “first recess” and “second recess” limitations, labeled as elements 34 and 100, respectively, in Figure 2 of the ‘641 patent reproduced below.

The IPR had only one instituted ground: that the challenged claims were obvious over the “Admitted Prior Art” and U.S. Patent No. 3,738,497 (“Betts”). The “Admitted Prior Art” included Figure 1. Betts discloses an airplane passenger seat with tilting backrest. Rather than a flat forward-facing wall, Betts discloses a contoured forward-facing wall to receive the tilted backrest. The Court noted that the “lower portion 30” of Betts slants rearwardly to provide space for a seatback 12 and the top 32 of the storage space 16 also slants rearwardly to not interfere with the seatback 12.

The PTAB had ruled that the Bett’s contoured wall design met the “first recess” limitation and that skilled artisans (airplane interior designers) would have been motivated to modify the flat forwardfacing wall of the lavatory in the Admitted Prior Art with Betts’s contoured, forward-facing wall to preserve space in the cabin.

While the cited art does not disclose the “second recess” to receive passenger seat supports, the Board agreed with Zodiac that creating a recess in the wall to receive the seat support was an obvious solution to a known problem and found that Zodiac “established a strong case of obviousness based on the Admitted Prior Art and Betts, coupled with common sense and the knowledge of a person of ordinary skill in the art.”

B/E’s appeal argued that the Board’s obviousness determination is erroneous because it improperly incorporated a second recess limitation not disclosed in the prior art.

Analysis

The CAFC determined that only the “second recess” limitation was at issue. They found no error in the PTAB’s approaches to finding the “second recess” obvious. First noting that the prior art yields a predictable result, the “second recess,” because a person of skill in the art would have applied a variation of the first recess and would have seen the benefit of doing so. The Court noted the evidence provided by Zodiac’s expert and quoted the often cited KSR recitation: “The combination of familiar elements according to known methods is likely to be obvious when it does no more than yield predictable results. . . . If a person of ordinary skill in the art can implement a predictable variation § 103 likely bars its patentability.” KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 416 (2007).

The Court further affirm the Board’s conclusion that the challenged claims would have been obvious because “it would have been a matter of common sense” to incorporate a second recess in the Admitted Prior Art/Betts combination. B/E argued that the Board legally erred by relying on “an unsupported assertion of common sense” to “fill a hole in the evidence formed by a missing limitation in the prior art.” The Court again cited KSR, noting that common sense teaches that familiar items may have obvious uses beyond their primary purposes, and in many cases a person of ordinary skill will be able to fit the teachings of multiple patents together like pieces of a puzzle. Id at 421. (“A person of ordinary skill is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton.”). They found the PTAB’s “invocation of common sense was properly accompanied by reasoned analysis and evidentiary support” noting that the Board dedicated more than eight pages of analysis to the “second recess” limitation and relied on detailed expert testimony.

The Court noted their decision in Perfect Web Techs, Inc. v. InfoUSA, Inc., that “[c]ommon sense has long been recognized to inform the analysis of obviousness if explained with sufficient reasoning.” 587 F.3d 1324, 1328 (Fed. Cir. 2009). They concluded that the Board properly adequately explained their reasoning that the missing claim limitation (the “second recess”) involves repetition of an existing element (the “first recess”) until success is achieved (reasoning that the logic of using a recess to receive the seat back applies equally to using another recess to receive the aft extending seat support).

The CAFC therefore affirmed the PTAB’s finding of the challenged claims unpatentable.

Take Aways

Patent holders need to be cautious in relying on simple limitations. Such limitations may be considered obvious even if not clearly recited in the prior art. Consideration of whether the use of common sense by a skilled artisan would result in the inclusion of the limitation needs to be taken into consideration.

Nexus for Secondary Considerations requires Coextensiveness between a product and the claimed invention

| June 26, 2020

Fox Factory, Inc. v. SRAM, LLC

May 18, 2020

Lourie, Mayer and Wallach. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary:

SRAM sued Fox Factory for infringing U.S. Patent 9,291,250 (the ‘250 patent) and the parent patent U.S. Patent 9,182,027 (the ‘027 patent) to bicycle chainrings having teeth that alternate between widened teeth that better fit a gap between outer plates of a chain and narrower teeth to fit a gap between inner plates of a chain. Fox Factory filed IPRs against each patent. SRAM provided evidence of secondary considerations and argued that a greater than 80% gap-filling feature of the X-Sync chainring was crucial to its success for solving chain retention problem. The PTAB held that both patents are not unpatentable as obvious relying in part on secondary consideration evidence provided by SRAM. On appeal, the CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision with regard to the ‘027 patent because the SRAM X-Sync chainring is not coextensive with the claims of the ‘027 patent that do not recite the greater than 80% gap-filling feature. However, the CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s decision for the ‘250 patent because the claims include the greater than 80% gap-filling feature.

Details:

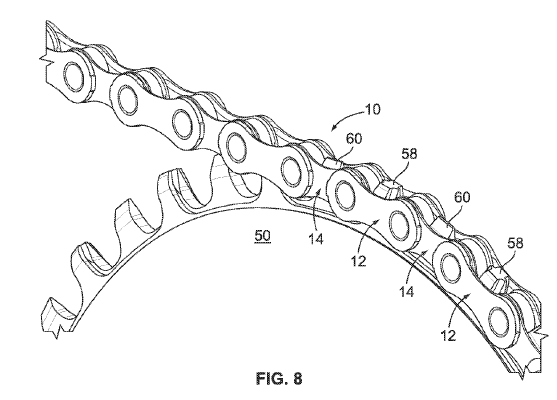

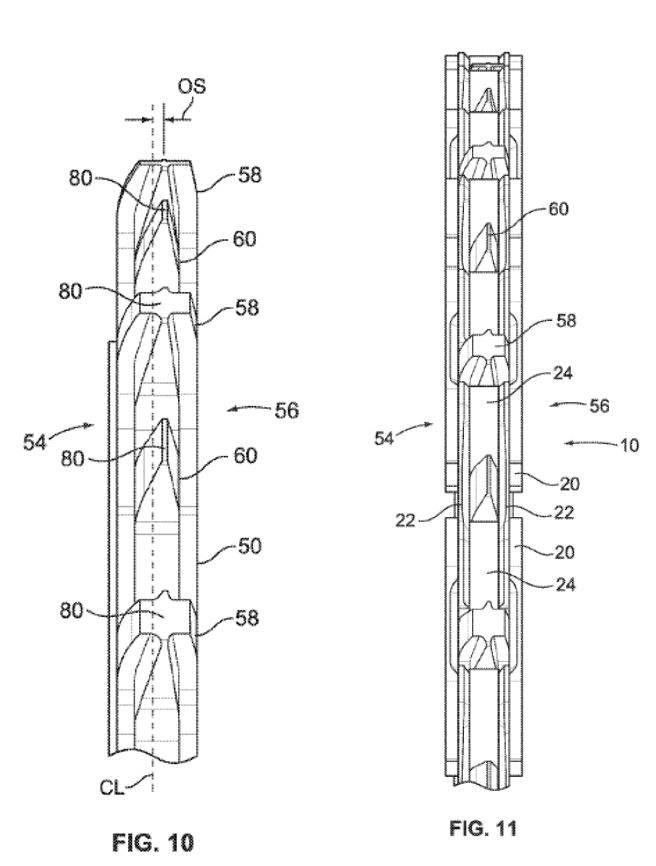

The ’250 patent and the ‘027 patent are to bicycle chainrings. Some figures of the patents are provided below.

This chainring is designed to be a solitary chainring that does not need to switch between different size chainrings. Since it is a solitary chainring, the chainring can be designed to provide a tighter fit with the chain. A conventional chain has links that are alternatingly narrow and wide, but the conventional chainring has teeth that are all the same size. SRAM designed a chairing to have alternating teeth having widened teeth to fit the wide gaps and narrow teeth to fit the narrower gaps. SRAM’s product the X-Sync chainring that implements this design has been praised for its chain retention.

Claim 1 of the ‘250 patent is provided:

1. A bicycle chainring of a bicycle crankset for engagement with a drive chain, comprising:

a plurality of teeth extending from a periphery of the chainring wherein roots of the plurality of teeth are disposed adjacent the periphery of the chainring;

the plurality of teeth including a first group of teeth and a second group of teeth, each of the first group of teeth wider than each of the second group of teeth; and

at least some of the second group of teeth arranged alternatingly and adjacently between the first group of teeth,

wherein the drive chain is a roller drive chain including alternating outer and inner chain links defining outer and inner link spaces, respectively;

wherein each of the first group of teeth is sized and shaped to fit within one of the outer link spaces and each of the second group of teeth is sized and shaped to fit within one of the inner link spaces; and

wherein a maximum axial width about halfway between a root circle and a top land of the first group of teeth fills at least 80 percent of an axial distance defined by the outer link spaces.

In the IPR for the ‘250 patent, Fox Factory cited JP S56-42489 to Shimano and U.S. Patent 3,375,022 to Hattan. Shimano teaches a bicycle chainring with widened teeth to fit into the outer chain links of a conventional chain. Hattan describes that a chainring’s teeth should fill between 74.6% and 96% of the inner chain link space. Fox Factory argued that the claims would have been obvious because one of ordinary skill in the art would have seen the utility in designing a chainring with widened teeth to improve chain retention as taught by Shimano, and one of ordinary skill in the art would have looked to Hattan’s teaching with regard to the percentage of the link space that should be filled.

The PTAB held the claims to be non-obvious because of the axial fill limitation “at the midpoint of the teeth.” The PTAB found that Hattan taught the fill percentage at the bottom of the tooth instead of at the midpoint. The PTAB also found that SRAM’s evidence of secondary considerations rebutted Fox Factory’s arguments of obviousness.

On appeal, Fox Factory argued that the only difference between the prior art and the claimed invention is that the fill limitation is measured halfway up the tooth. Regarding secondary considerations, Fox Factory argued that a nexus between the claimed invention and the evidence of success of the X-Sync chainring was not demonstrated because the success is due to other various unclaimed aspects of the X-Sync chainring.

The CAFC stated that Fox Factory is correct that “a mere change in proportion … involves no more than mechanical skill, rather than the level of invention required by 35 U.S.C. § 103.” However, the CAFC stated that the PTAB “found that SRAM’s optimization of the X-Sync chainring’s teeth, as claimed in the ‘250 patent, displayed significant invention.” The CAFC pointed out that SRAM provided evidence that the success of the X-Sync chainring surprised skilled artisans, evidence of industry skepticism and subsequent praise, and evidence of a long-felt need to solve chain retention problems. The X-Sync chainring also won an award for “Innovation of the Year.” Based on the evidence, the CAFC stated that the PTAB did not err in concluding that the evidence of secondary considerations defeated the contention of routine optimization.