Result-Effective-Ugh…a Bridge Too Far?

| April 25, 2024

Pfizer Inc. v. Sanofi Pasteur Inc.

Decided: March 5, 2024

Result-Effective Variable; Obviousness

Before LOURIE, BRYSON, and STARK, Circuit Judge. Opinion drafted by LOURIE.

Summary:

Pfizer appealed to the Federal Circuit following rulings from five inter partes review proceedings petitioned by Sanofi challenging all claims of Pfizer’s U.S. Patent No. 9492559 (‘559 Patent). The ‘559 Patent claims immunogenic compositions comprising glycoconjugates of various Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes for use in pneumococcal vaccines. Independent claim 1 is as follows (emphasize added):

- An immunogenic composition comprising a Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 22F glycoconjugate, wherein the glycoconjugate has a molecular weight of between 1000 kDa and 12,500 kDa and comprises an isolated capsular polysaccharide from S. pneumoniae serotype 22F and a carrier protein, and wherein a ratio (w/w) of the polysaccharide to the carrier protein is between 0.4 and 2.

The Board instituted review based on each petition and issued final written decisions which, taken together, found all claims unpatentable. Pfizer raised four challenges on appeal. The first, which will be the only challenge discussed herein, alleged that the Board erred in determining that the ‘559 Patent was obvious based on prior art references PCT Patent Application Publication 2007/071711 (“GSK-711”) and U.S. Patent Application Publication 2011/0195086 (“Merck-086”).

The Board recognized that neither GSK-711 nor Merck-086 disclosed any molecular weight for a S. pneumoniae serotype 22F glycoconjugate, as required by claim 1 of the ’559 Patent, but nevertheless concluded that, based on the evidence of record, glycoconjugate molecular weight is a result-effective variable that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to optimize to provide a conjugate having improved stability and good immune response. It is here that Pfizer argued the Board erred, because it is undisputed that the prior art does not disclose any molecular weight for the claimed serotype 22F glycoconjugate, there could be no presumption of obviousness. The CAFC disagreed.

The CAFC begin by stating that “the determination whether or not a claimed parameter is a result-effective variable is merely one aspect of a broader routine optimization analysis.”

The CAFC followed that “an overlap between a claimed range and a prior art range creates a presumption of obviousness that can be rebutted with evidence that the given parameter was not recognized as result-effective. See Genentech, Inc. v. Hospira, Inc., 946 F.3d 1333, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (citing E.I. DuPont, 904 F.3d at 1006); In re Applied Materials, Inc., 692 F.3d 1289, 1295 (Fed. Cir. 2012).” However, they emphasized that this “does not mean that the determination whether or not a variable is result-effective is only appropriate when there is such an overlap.” Rather that “a routine optimization analysis generally requires consideration whether a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated, with a reasonable expectation of success, to bridge any gaps in the prior art to arrive at a claimed invention. Where that gap includes a parameter not necessarily disclosed in the prior art, it is not improper to consider whether or not it would have been recognized as result-effective. If so, then the optimization of that parameter is “normally obvious.” In re Antonie, 559 F.2d 618, 620 (CCPA 1977).”

Thus, the CAFC concluded that the Board did not err in considering, as part of its obviousness analysis, whether or not the claimed molecular weight of a S. pneumoniae serotype 22F glycoconjugate was a result-effective variable, dispute the cited references being silent thereon.

It was ultimately concluded that “substantial evidence supports the Board’s conclusion that the molecular weight recited in claim 1 would have been obvious over the references.” Such evidence included the fact that GSK-711 gave the molecular weights for fourteen other S. pneumoniae serotype glycoconjugates, and that Expert Testimony showed that, at the time of the invention, conjugation techniques and conditions were routine such that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood the claimed molecular weight to be “typical of immunogenic conjugates.”

Comments:

An argument against a Result-Effective Variable assertion may be weakened, even when the prior art is silent on said variable, if a PHOSITA can bridge the gaps in the teaching with a reasonable success based on the evidence overall. Thus, it may be necessary to demonstrate more than simply the variable not being recognized by the reference. That is, one may also have to show there is no reasonable expectation of success in said variable

THE DOMESTIC INDUSTRY REQUIREMENT FOR AN ITC COMPLAINT CAN BE SATISFIED BASED ON A SUBSET OF A PRODUCT IF THE IP INVOLVES ONLY THAT SUBSET

| March 22, 2024

Roku, Inc. v. ITC

Decided: January 19, 2024

Before Dyk, Hughes, and Stoll. Opinion by Hughes.

Summary:

Universal Electronics, Inc. (“Universal”) filed a complaint against Roku in the International Trade Commission (ITC) for importing certain TV products that infringe U.S. Patent No. 10,593,196. The issues on appeal include whether the final determination of the ITC is proper in finding that (1) Universal had ownership rights to assert the ‘196 patent in the complaint; (2) Universal satisfied the economic prong of the domestic industry requirement under 19 U.S.C. § 1337(a)(3)(C) to bring a complaint at the ITC; and (3) Roku failed to demonstrate that the ‘196 patent was obvious over the prior art. The CAFC affirmed the ITC’s findings.

Details:

The ‘196 patent is to a device for allowing communication between various devices such as smart TVs and DVD players that may use different communication protocols such as wired connections (e.g., HDMI) or wireless communication (Wi-Fi or Bluetooth) that may be incompatible with each other. The ‘196 patent discloses a universal control engine (referred to as a “first media device” in the claims) that can scan various target devices (referred to as “second media devices” in the claims). The first media device receives wireless signals from various devices such as a remote control or an app on a tablet computer and can transmit commands using wired or IR signals to controllable devices such as TVs, DVRs or a DVD player.

Claim 1 is provided:

1. [pre] A first media device, comprising:

[a] a processing device;

[b] a high-definition multimedia interface communications port, coupled to the processing device, for communicatively connecting the first media device to a second media device;

[c] a transmitter, coupled to the processing device, for communicatively coupling the first media device to a remote control device; and

[d] a memory device, coupled to the processing device, having stored thereon processor executable instruction;

[e] wherein the instructions, when executed by the processing device,

[i] cause the first media device to be configured to transmit a first command directly to the second media device, via use of the high-definition multimedia communications port, to control an operational function of the second media device when a first data provided to the first media device indicates that the second media device will be responsive to the first command, and

[ii] cause the first media device to be configured to transmit a second data to a remote control device, via use of the transmitter, for use in configuring the remote control device to transmit a second command directly to the second media device, via use of a communicative connection between the remote control device and the second media device, to control the operational function of the second media device when the first data provided to the first media device indicates that the second media device will be unresponsive to the first command.

1. Ownership Issue

After filing its complaint, Universal filed a petition for correction of inventorship to add an inventor (Mr. Barnett) to the patent. Roku had filed a motion for summary determination before the ALJ that Universal lacked standing to assert the ‘196 patent because at the time Universal filed its complaint, it did not own all rights to the ‘196 patent. Roku argued that a 2004 agreement between Mr. Barnett and Universal did not constitute an assignment of rights.

The ALJ agreed stating that the 2004 agreement was a “mere promise to assign rights in the future, not an immediate transfer of expectant rights,” and thus, the 2004 agreement “did not automatically assign any of Mr. Barnett’s rights to the Provisional Applications of the ‘196 patent that eventually issued from the priority chain.”

The Commission reversed stating that there was a separate agreement in 2012 in which Mr. Barnett assigned all his rights to a series of provisional applications including the provisional which led to the ‘196 patent. The language of the assignment states that Mr. Barnett “hereby sell[s] and assign[s] … [his] entire right, title, and interest in and to the invention,” including “all divisions and continuations thereof, including the subject-matter of any and all claims which may be obtained in every such patent.” The Commission further found that Mr. Barnett did not contribute any new or inventive matter to the ‘196 patent after filing the provisional applications. The Commission found that the 2012 agreement constituted a “present conveyance” of Mr. Barnett’s rights in the ‘196 patent. The CAFC agreed with the Commission that the agreement constitutes a “present conveyance,” and thus, Universal had ownership rights to assert the ‘196 patent.

2. Domestic Industry Requirement – Economic Prong

To bring complaint at the ITC under Section 337, the complainant must possess a domestic industry in the United States. Domestic industry can be satisfied by showing “substantial investment in [a patent’s] exploitation, including engineering, research and development, or licensing.” 19 U.S.C. § 1337(a)(3)(C).

The Commission found that Universal had substantial investments in domestic engineering and R&D related to a platform called QuickSet which is incorporated into multiple smart TVs. The Commission found that the QuickSet platform involves software and software updates that result in practice of the asserted claims when implemented on the Samsung DI products and that Universal’s asserted expenditures are attributable to its domestic investments in R&D and engineering. The Commission further found that Universal’s investments go directly to the functionality necessary to practice many claimed elements of the ‘196 patent. The CAFC held that the Commission’s findings are supported by substantial evidence.

Roku attempted to frame the argument with regard to the TV as a whole rather than the QuickSet technology that is installed on those TVs to argue that Universal has not satisfied the domestic industry requirement. However, the CAFC stated that the domestic industry requirement “does not require expenditures in whole products themselves, but rather, sufficiently substantial investment in the exploitation of the intellectual property.” The CAFC further stated “a complainant can satisfy the economic prong of the domestic industry requirement based on expenditures related to a subset of a product, if the patent(s) at issue only involve that subset.” The CAFC held that the IP at issue in this case is practiced by QuickSet and the related QuickSet technologies, which is a subset of the entire TV.

3. Obviousness

Roku argued obviousness of the claims based on prior art references Chardon and Mishra. The parties agreed that Chardon disclosed all of the limitations of claim 1 except for limitation 1[e][ii]. Roku cited Mishra for teaching this feature. The ALJ found that Universal had presented evidence of secondary considerations showing that QuickSet satisfied a long-felt but unmet need that outweighed Roku’s obviousness case. The Commission went further regarding non-obviousness finding that the combination of Chardon and Mishra does not disclose a system that automatically configures two different control devices to transmit commands over different pathways. The Commission further found that Roku failed to present clear and convincing evidence of a motivation to combine the references.

On appeal, Roku merely argued that the Commission erred by accepting Universal’s evidence of secondary considerations. Roku argued that the Commission erred in finding a nexus between the secondary considerations of non-obviousness and the claims because some of the news articles presented by Universal discuss features in addition to QuickSet. The CAFC held that this argument is meritless because Roku did not dispute that QuickSet is discussed in the references that the Commission relied on.

The CAFC further stated that Roku did not challenge the actual findings that the combination of Chardon and Mishra does not disclose limitation 1[e], i.e., allowing for a choice between different second media devices. Thus, the Commission’s obviousness determination was affirmed.

Comments

When filing a patent infringement suit, make sure inventorship and ownership are clear, and make any necessary corrections before filing suit. When filing a complaint at the ITC, keep in mind that the domestic industry requirement does not require showing expenditures on whole products if the patent at issue only involves a subset of the product.

Why not to be conclusory!

| September 6, 2023

Volvo Penta of the Ams. LLC v. Brunswick Corp.

Decided: August 24, 2023

Before Moore, Chief Judge, Lourie and Cunningham, Circuit Judges. Authored by Chief Judge, Lourie.

Summary:

The CAFC vacated a Final Written Decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) holding all claims of U.S. Patent 9,630,692 (the “’962 patent”), owned by Volvo Penta, unpatentable as obvious. The court remanded the decision for further evaluation of objective indicia of non-obviousness that the Board had not adequately considered.

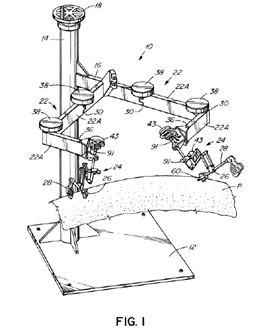

- A steerable tractor-type drive for a boat, comprising:

a drive support mountable to a stern of the boat;

a drive housing pivotally attached to the support about a steering axis, the drive housing having a vertical drive shaft connected to drive a propeller shaft, the propeller shaft extending from a forward end of the drive housing;

at least one pulling propeller mounted to the propeller shaft,

wherein the steering axis is offset forward of the vertical drive shaft.

The ’962 patent is directed to a boat drive, designed to provide a “pulling-type” or “forward facing drive” positioned under the stern of the boat. Claim 1 of the ’692 patent, reproduced below, is representative.

In 2015, Volvo Penta launched its commercial embodiment of the ’692 patent, the ‘Forward Drive.’ This product became extremely successful once available, particularly for wakesurfing and other water sports.

In August 2020, Brunswick Corp. (“Brunswick”) launched its own drive that also embodied the ’692 patent, the ‘Bravo Four S.’ The same day that Brunswick launched the Bravo Four S, it petitioned for inter partes review of all claims of the ’692 patent. Relevant to this appeal, Brunswick asserted that the challenged claims would have been obvious based on the references, Kiekhaefer and Brandt. Kiekhaefer is a 1952 patent assigned to Brunswick and directed to an outboard motor that could have either rear-facing or forward-facing propellers. Brandt is a 1989 patent assigned to Volvo Penta and directed to a stern drive with rear-facing propellers.

Volvo Penta position was not that the references combined failed to disclose all the claim elements, but rather that there was a lack of motivation to combine said references. Volvo Penta further proffered evidence of six objective indicia of non-obviousness: copying, industry praise, commercial success, skepticism, failure of others, and long-felt but unsolved need.

Ultimately, the Board had found Volvo Penta’s position unpersuasive asserting that sufficient motivation was found and that Volvo Penta’s objective evidence of secondary considerations was insufficient to outweigh Brunswick’s “strong evidence of obviousness.”

Accordingly, Volvo Penta raises three main arguments on appeal: (1) that the Board’s finding of motivation to combine was not supported by substantial evidence, (2) that the Board erred in its determination that there was no nexus, and (3) that the Board erred in its consideration of Volvo Penta’s objective evidence of secondary considerations of nonobviousness.

The court discussed each one in turn:

- Motivation:

The court began:

The ultimate conclusion of obviousness is a legal determination based on underlying factual findings, including whether or not a relevant artisan would have had a motivation to combine references in the way required to achieve the claimed invention. Henny Penny Corp. v. Frymaster LLC, 938 F.3d 1324, 1331 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (citing Wyers v. Master Lock Co., 616 F.3d 1231, 1238–39 (Fed. Cir. 2010)).

Volvo Penta first argued that the Board ignored a number of assertions in its favor, including: (1) that Brunswick, despite having knowledge of Kiekhaefer for decades, never attempted the proposed modification itself; (2) that Brunswick’s proposed modification would have entailed a nearly total and exceedingly complex redesign of the drive system; (3) the complexity of and difficulty in shifting the vertical drive shaft of Kiekhaefer; and (4) that Brunswick itself attempted to make its proposed modification yet failed to create a functional drive. The court disagreed on all points.

The Board acknowledged the testimony of Volvo Penta’s expert that a “complete redesign of Brandt” would be necessary, including “over two dozen modifications,” but ultimately found that not all of the identified changes would have been required to arrive at the claimed invention.

Volvo Penta also argued that the Board’s reliance on Kiekhaefer for motivation to combine was misplaced. The Board had relied on Kiekhaefer teaching that a “tractor-type propeller” is “more efficient and capable of higher speeds.” Volvo Penta argued this is not the metric by which recreational boats are measured.

However, again, the court disagreed stating that while ‘it is likewise not conclusive that speed may not be the primary or only metric by which recreational boats are measured. Substantial evidence supports a finding that speed is at least a consideration.’

The CAFC thus upheld the Board’s finding that motivation to combine was supported by substantial evidence.

II. Nexus

The Court began:

For objective evidence of secondary considerations to be relevant, there must be a nexus between the merits of the claimed invention and the objective evidence. See In re GPAC, 57 F.3d 1573, 1580 (Fed. Cir. 1995). A showing of nexus can be made in two ways: (1) via a presumption of nexus, or (2) via a showing that the evidence is a direct result of the unique characteristics of the claimed invention.

A patent owner is entitled to a presumption of nexus when it shows that the asserted objective evidence is tied to a specific product that “embodies the claimed features, and is coextensive with them.” Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. v. Philip Morris, Inc., 229 F.3d 1120, 1130 (Fed. Cir. 2000).When a nexus is presumed, “the burden shifts to the party asserting obviousness to present evidence to rebut the presumed nexus.” Id.; see also Yita LLC v. MacNeil IP LLC, 69 F.4th 1356, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2023). The inclusion of noncritical features does not defeat a finding of a presumption of nexus. See, e.g., PPC Broadband, Inc. v. Corning Optical Commc’ns RF, LLC, 815 F.3d 734, 747 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (stating that a nexus may exist “even when the product has additional, unclaimed features”)

Initially, for a presumption of nexus, there is a requirement that the product embodies the invention and is coextensive with it. Brown & Williamson, 229 F.3d at 1130. The CAFC noted that neither party disputed that both the Forward Drive and the Bravo Four S embodied the claimed invention. See, e.g., J.A. 1211, 117:10–25, but emphasized that coextensiveness is a separate requirement. Fox Factory, 944 F.3d at 1374.

Volvo Penta, as Brunswick and the Board note, did not provide sufficient argument on coextensiveness. Rather, it submitted a mere sentence that the Forward Drive is a “commercial embodiment” of the ‘692 Patent and “coextensive with the claims”. The Board found this argument “conclusory” and the CAFC agreed. As above, “[t]he patentee bears the burden of showing that a nexus exists.” Fox Factory, 944 F.3d at 1373 (quoting WMS Gaming Inc. v. Int’l Game Tech., 184 F.3d 1339, 1359 (Fed. Cir. 1999)).

However, the court found that the Boards finding of a lack of nexus, independent of a presumption, not supported by evidence. Specifically, the Board found that Brunswick’s development of the Bravo Four S was “akin to ‘copying,’” and that its “own internal documents indicate that the Forward Drive product guided [Brunswick] to design the Bravo Four S in the first place.” Indeed, the undisputed evidence, as the Board found, shows that boat manufacturers strongly desired Volvo Penta’s Forward Drive and were urging Brunswick to bring a forward drive to market.

The court found that there is therefore a nexus between the unique features of the claimed invention, a tractor-type stern drive, and the evidence of secondary considerations.

III. Objective Indicia

The court began:

Objective evidence of nonobviousness includes: (1) commercial success, (2) copying, (3) industry praise, (4) skepticism, (5) long-felt but unsolved need, and (6) failure of others. See, e.g., Transocean Offshore Deepwater Drilling, Inc. v. Maersk Drilling U.S., Inc., 699 F.3d 1340, 1349–56 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The weight to be given to evidence of secondary considerations involves factual determinations, which we review only for substantial evidence. In re Couvaras, 70 F.4th 1374, 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2023).

The court found that “the Board’s analysis of [this] objective indicia of non-obviousness, including its assignments of weight to different considerations, was overly vague and ambiguous.”

For example, despite recognizing the importance of Brunswick internal documents demonstrating deliberate copying of the Forward Drive, and “finding copying, the Board only afforded this factor ‘some weight.’” The Federal Circuit held that this “assignment of only ‘some weight’” was insufficient in view of its precedent, which generally explains that “copying [is] strong evidence of non-obviousness,” and the “failure by others to solve the problem and copying may often be the most probative and cogent evidence of non-obviousness.” Panduit Corp. v. Dennison Mfg. Co., 774 F.2d 1082, 1099 (Fed. Cir. 1985), cert. granted, judgment vacated on other grounds, 475 U.S. 809 (1986) (“That Dennison, a large corporation with many engineers on its staff, did not copy any prior art device, but found it necessary to copy the cable tie of the claims in suit, is equally strong evidence of nonobviousness.”).

Regarding commercial success, the Board recognized that the record supported, and Brunswick did not contest, that boat manufacturers “strongly desired Volvo Penta’s Forward Drive and were urging Brunswick to bring a forward drive to market.” Nevertheless, the Board only afforded this factor “some weight.” The court stated that this finding was not supported by substantial evidence.

Regarding industry praise, the Board found that although the exhibits submitted “provide praise for the Forward Drive more generally, including mentioning its forward facing propellers, as claimed in the ’692 patent,” it also found that “many of the statements of alleged praise specifically discuss unclaimed features, such as adjustable trim and exhaust-related features.”

The court noted that the Board assigned industry praise, commercial success, and copying all “some weight” without explaining why it gave these three factors the same weight. The court concluded this was ambiguous, and so the Board had “failed to sufficiently explain and support its conclusions. See, e.g., Pers. Web Techs., LLC v. Apple, Inc., 848 F.3d 987, 993 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (remanding in view of the Board’s failure to “sufficiently explain and support [its] conclusions”); In re Nuvasive, Inc., 842 F.3d 1376, 1385 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (same).”

Next, the Court also determined that the Board failed to properly evaluate long-felt but unresolved need. In evaluating the evidence presented by Volvo Penta, the Board dismissed it as merely describing the benefits of the product without indicating a long-felt problem that others had failed to solve. Volvo Penta had cited articles in support of its position, but the Board, without explanation, gave the arguments very little weight. Upon review, the CAFC stated that the articles identified more than mere benefits and “indisputably identifies a long-felt need: safe wakesurfing on stern-drive boats.”

The CAFC touches upon the relevance of the time since the issuance of cited references. The CAFC agreed with the Board that “the mere passage of time from dates of the prior art to the challenged patents” does not indicate nonobviousness “their age can be relevant to long-felt unresolved need.” See Leo Pharm. Prods., 726 F.3d 1346, 1359 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (“The length of the intervening time between the publication dates of the prior art and the claimed invention can also qualify as an objective indicator of nonobviousness.”); cf. Nike, Inc. v. Adidas AG, 812 F.3d 1326, 1338 (Fed. Cir. 2016), overruled on other grounds by Aqua Prods., Inc. v. Matal, 872 F.3d 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The CAFC stated that other factors such as “lack of market demand” can explain why a product was not developed for years, even decades after the prior art. However, when, as here, “evidence demonstrates that there was a market demand for at least” a period of that time (here, the market demand only existed for ten of the fifty years from the prior art reference), the fact that Brunswick itself owned one of the asserted should not be overlooked. That, it is certainly relevant that the asserted patents were long in existence and not obscure, but rather owned by the parties in this case.

Finally, the CAFC held that the Board’s ultimate conclusion that “Brunswick’s “strong evidence of obviousness outweighs Patent Owner’s objective evidence of nonobviousness” lacked a proper explanation for said conclusion.

Thus, ultimately the Court found that the Board failed to properly consider the evidence of objective indicia of nonobviousness and so vacated and remanded for further consideration consistent with the opinion.

Comments:

Motivation to combine a reference does not require a recognition of the primary or only metric by which an invention is measured, so long as it is at least a consideration.

Regarding a presumption of nexus, be reminded that (i) coextensiveness is a separate element and should be addressed as such; and that (ii) “[t]he patentee bears the burden of showing that a nexus exists” and this requires more than conclusory statements. Similarly, the PTO must support a finding of a lack of nexus with evidence not mere conclusory statements.

It also serves as a reminder to be thoughtful and thorough in presenting objective indicia of nonobviousness, not only during IPRs and other forms of litigation, but in prosecution too. Avoid citing arguments in conclusory fashion.

Tags: Motivation > nexus > objective indicia of nonobviousness > obviousness > secondary considerations

The Testimony of an Expert Without the Requisite Experience Would Be Discounted in the Obviousness Determination

| October 21, 2022

Best Medical International, Inc., v. Elekta Inc.

Before HUGHES, LINN, and STOLL, Circuit Judges. STOLL, Circuit Judge.

Summary

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s determination that challenged claims are unpatentable as obvious over the prior art.

Background

Best Medical International, Inc (BMI) owns the patent at issue, U.S. Patent No. 6,393,096 (‘096). Patent ‘096 is directed to a medical device and method for applying conformal radiation therapy to tumors using a pre-determined radiation dose. The device and the method are intended to improve radiation therapy by computing an optimal radiation beam arrangement that maximizes radiation of a tumor while minimizing radiation of healthy tissue. Claim 43 is listed below as representative of the claims:

43. A method of determining an optimized radiation beam arrangement for applying radiation to at least one tumor target volume while minimizing radiation to at least one structure volume in a patient, comprising the steps of:

distinguishing each of the at least one tumor target volume and each of the at least one structure volume by target or structure type;

determining desired partial volume data for each of the at least one target volume and structure volume associated with a desired dose prescription;

entering the desired partial volume data into a computer;

providing a user with a range of values to indicate the importance of objects to be irradiated;

providing the user with a range of conformality control factors; and

using the computer to computationally calculate an optimized radiation beam arrangement.

Varian Medical Systems, Inc. filed two IPR petitions challenging some claims of the ’096 patent. Soon after the Board instituted both IPRs, Elekta Inc. filed petitions to join Varian’s instituted IPR proceedings. The Board issued the final written decisions that determined the challenged claims 1, 43, 44, and 46 were unpatentable as obvious.

Prior to the Board’s final decisions, BMI canceled claim 1 in an ex parte reexamination where the Examiner rejected claim 1 based on the finding of statutory and obviousness-type double patenting. Although BMI had canceled claim 1, the Board still considered the merits of Elekta’s patentability challenge for claim 1 and concluded that claim 1 was unpatentable in its final decision. The Board explained that claim 1 had not been canceled by final action as BMI had “not filed a statutory disclaimer.” BMI appealed the Board’s final written decisions. Varian later withdrew from the appeal.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit first addressed the threshold question of jurisdiction. BMI asked for a vacatur of the Board’s patentability determination by arguing “the Board lacked authority to consider claim 1’s patentability because that claim was canceled before the Board issued its final written decision, rendering the patentability question moot.” The Federal Circuit found that it was proper for the Board to address every challenged claim during the IPR under the Supreme Court’s decision in SAS Institute Inc. v. Iancu in which the Supreme Court held that the Board in its final written decision “must address every claim the petitioner has challenged.” 138 S. Ct. 1348, 1354 (2018) (citing 35 U.S.C. § 318(a)). Furthermore, the Federal Circuit supported Elekta’s argument that BMI lacked standing to appeal the Board’s unpatentability determination. The Federal Circuit explained that BMI admitted during oral argument that claim 1 was canceled prior to filing its notice of appeal without challenging the rejections. Thus, the Federal Circuit found that there was no longer a case or controversy regarding claim 1’s patentability at that time. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit dismissed BMI’s appeal regarding claim 1 for lack of standing.

The Federal Circuit later moved to consider BMI’s challenges to the Board’s findings regarding the level of skill in the art, motivation to combine, and reasonable expectation of success. The Board’s finding put a requirement on the level of skill in the art that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have had “formal computer programming experience, i.e., designing and writing underlying computer code.” BMI’s expert did not have such requisite computer programming experience. Thus, BMI’s expert testimony was discounted in the Board’s obviousness analysis.

The Federal Circuit stated that there is a non-exhaustive list of factors in finding the appropriate level of skill in the art, these factoring including: “(1) the educational level of the inventor; (2) type of problems encountered in the art; (3) prior art solutions to those

problems; (4) rapidity with which innovations are made; (5) sophistication of the technology; and (6) educational level of active workers in the field.” The Federal Circuit found that both parties did not provide sufficient evidence relating to these factors. Elekta principally relied on its expert Dr. Kenneth Gall’s declaration, whereas BMI relied on Mr. Chase’s declaration. In Dr. Gall opinion, a person of ordinary skill in the art would have had “two or more years of experience in . . . computer programming associated with treatment plan optimization.” Mr. Chase only disagreed with “the requirement,” but did not provide any explanation as to why “the requirement of ‘two or more years of . . . computer programming associated with treatment plan optimization’” was “inappropriate.”

Despite competing expert testimony on a person of ordinary skill, the Federal Circuit took the Board’s side and held that the Board relied on “the entire trial record,” including the patent’s teachings as a whole, to conclude the level of skill in the art. The Federal Circuit cited several sentences from the specification of the ‘096 patent to explain why the Board was reasonable to conclude that a skilled artisan would have had formal computer programming experience. For example, representative claim 43 was cited, which recites “using the computer to computationally calculate an optimized radiation beam arrangement.” The written description in ‘096 patent also recites “optimization method may be carried out using . . . a conventional computer or set of computers, and plan optimization software, which utilizes the optimization method of the present invention.”

The Federal Circuit found that BMI’s additional arguments were unpersuasive. BMI argued that the claims require that one specific step must be accomplished using a single computer and the claimed “conformality control factors” are “mathematically defined parameter[s].” The Federal Circuit concluded that there is no error in the Board’s determination based on the plain claim language and written description. BMI also argued that the Board’s finding that the prior teaches “providing a user with a range of values to indicate the importance of objects to be irradiated” is unsupported by substantial evidence. The Federal Circuit was not persuaded, because Dr. Gall’s testimony provide the support that a skilled artisan would have found the feature obvious.

BMI also challenged the Board’s findings as to whether there would have been a motivation to combine the prior art of Carol-1995 with Viggars and whether a skilled artisan would have had a reasonable expectation of success. But the Federal Circuit found that the Board relied on the teachings of the references themselves to support both findings. Thus, it was concluded that the Board’s well-reasoned analysis was supported by substantial evidence.

Takeaway

- The level of skill in the art could be defined in the specification for determining obviousness.

- The testimony of an expert without the requisite experience would be discounted in the obviousness arguments.

General industry skepticism may not be sufficient by itself to preclude a finding of motivation to combine

| August 2, 2022

Auris Health, Inc. v. Intuitive Surgical Operations, Inc.

Decided: April 29, 2022

Prost (author), Dyke, and Reyna (dissenting)

Summary:

The Federal Circuit rejected the PTAB’s obviousness decision by holding that general industry skepticism is not relevant to the question of obviousness.

Details:

In 2018, Intuitive Surgical sued Auris Health for patent infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,142,447 (“the ’447 patent”).

The ’447 patent

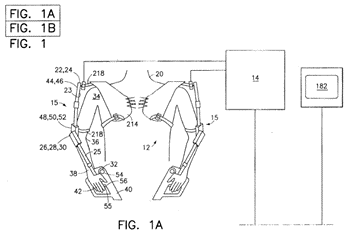

This patent is directed to robotic surgery systems.

The ’447 patent describes “an improvement over Intuitive’s earlier robotic surgery systems, which allow surgeons to remotely manipulate surgical tools using a controller.”

The ’447 patent attempts to solve problems (doctors must swap out various surgical instruments and this step could be tricky in a robotic surgical system where space is limited, different ranges of motion must be calibrated for different surgical instruments, and time is need to interchange those instruments) in the surgery via a robotic system with a servo-pulley mechanism so that doctors could swap out surgical instruments and reduce surgery time, improve safety, and increase reliability of the system.

PTAB

The PTAB determined that the prior art references asserted by Aurie – Smith and Faraz – disclosed each limitation of the claims in the ’447 patent.

The only remaining issue is whether a skilled artisan would have motivated to combine these two references.

Smith discloses “a robotic surgical system that uses an exoskeleton controller, worn by a clinician, to remotely manipulate a pair of robotic arms, each of which holds a surgical instrument.” Smith discloses that the clinician may direct an assistant to relocate the arms as necessary.

Faraz is directed an adjustable support stand that holds surgical instruments. Faraz discloses that its stand “may enable a surgeon to perform surgery with fewer assistants” because its stand “can support multiple surgical implements while [they] are being moved” and “can also provide support for a surgeon’s arms during long or complicated surgery.”

Auris argued that a skilled artisan would be motivated to combine these references to decrease the number of assistants necessary for surgery.

Intuitive argued that a skilled artisan would not be motivated to combine these references because “surgeons were skeptical about performing robotic surgery in the first place, [so] there would have been no reason to further complicate Smith’s already complex robotic surgical system with [Faraz’s] roboticized surgical stand.”

The PTAB agreed with Intuitive that there is no motivation to combine these references because there is skepticism at the time of the invention for using robotic systems during surgery in the first place.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit held that general industry skepticism cannot, by itself, preclude a finding of motivation to combine.

The Federal Circuit noted that the evidence of skepticism must be specific to the invention, not generic to the field and that Intuitive provided not case law to suggest that the PTAB can rely on generic industry skepticism to find a lack of motivation of combine.

The Federal Circuit held that the PTAB was wrong to exclusively rely on Intuitive’s expert testimony that “there was great skepticism for performing telesurgery” at the time of the invention and, as a result, a skilled artisan “would not have been compelled to complicate Smith’s system further.”

Therefore, the Federal Circuit remand for further consideration of the parties’ motivation-to-combine evidence.

Dissent

Judge Reyna noted that the PTAB’s determination that Auris failed to show a motivation to combine is adequately supported by substantial evidence and was not contrary to our law on obviousness.

While Judge Reyna agreed that skilled artisans’ general skepticism toward robotic surgery, by itself, could be insufficient to negate a motivation to combine, he disagreed that it could never support a finding of no motivation to combine.

Judge Reyna believes that the majority’s inflexible and rigid rule appears to be in tension with the central thrust of KSR (rejecting the “rigid approach of the Court of Appeals” and articulating an “expansive and flexible approach” of determining obviousness).

Takeaway:

- General industry skepticism may not be sufficient by itself to preclude a finding of motivation to combine.

- Specific evidence of industry skepticism related to a specific combination of references might contribute to finding a lack of motivation to combine.

APPLE MAKES ROTTEN CONVINCING THAT THE PTAB CANNOT CONSTRUE CLAIMS PROPERLY

| April 7, 2022

Apple, Inc vs MPH Technologies, OY

Decided: March 9, 2022

MOORE, Chief Judge, PROST and TARANTO. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

Apple appealed losses on 3 IPRs attempting to convince the CAFC that the PTAB had misconstrued numerous dependent claims for a myriad of reasons. The CAFC sided with the Board on all counts, in general showing deference to the PTAB and its ability to properly interpret claims.

Background:

Apple appealed from 3 IPRs wherein the PTAB had held Apple failed to show claims 2, 4, 9, and 11 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,494; claims 7–9 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,502; and claims 3, 5, 10, and 12–16 of U.S. Patent No. 9,838,362 would have been obvious. Apple’s IPR petitions relied primarily on a combination of Request for Comments 3104 (RFC3104) and U.S. Patent No. 7,032,242 (Grabelsky).

The patents disclose a method for secure forwarding of a message from a first computer to a second computer via an intermediate computer in a telecommunication network in a manner that allowed for high speed with maintained security.

The claims of the ’494 and ’362 patents cover the intermediate computer. Claim 1 of the ’494 patent was used as the representative independent claim for the patents:

1. An intermediate computer for secure forwarding of messages in a telecommunication network, comprising:

an intermediate computer configured to connect to a telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to be assigned with a first network address in the telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address having an encrypted data payload of a message and a unique identity, the data payload encrypted with a cryptographic key derived from a key exchange protocol;

the intermediate computer configured to read the unique identity from the secure message sent to the first network address; and

the intermediate computer configured to access a translation table, to find a destination address from the translation table using the unique identity, and to securely forward the encrypted data payload to the destination address using a network address of the intermediate computer as a source address of a forwarded message containing the encrypted data payload wherein the intermediate computer does not have the cryptographic key to decrypt the encrypted data payload.

The ’502 patent claims the mobile computer that sends the secure message to the intermediate computer.

Decision:

The Court first looked at dependent claim 11 of the ’494 patent and dependent claim 12 of the ’362 patent requirement that “the source address of the forwarded message is the same as the first network address.”

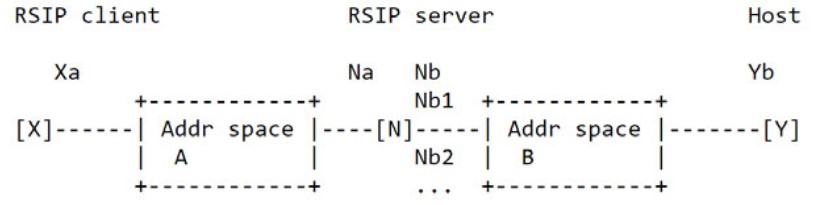

Apple had asserted RFC3104 disclosed this aspect of the claims. Specifically, RFC3104 discloses a model wherein an RSIP server examines a packet sent by Y destined for X. “X and Y belong to different address spaces A and B, respectively, and N is an [intermediate] RSIP server.” N has two addresses: Na on address space A and Nb on address space B, which are different. Apple asserted the message sent from Y to X is received by RSIP server N on the Nb interface and then must be sent to Na before being forwarded to X.

The model topography for RFC3104 is illustrated as:

In light thereof, Apple asserted that because the intermediate computer sends the message from Nb to Na before forwarding it to X, Na is both a first network address and the source address of the forwarded message. That the message was not sent directly to Na, Apple claimed, was of no import given the claim language. The Board had disagreed and found there was no record evidence that the mobile computer sent the message directly to Na.

In the appeal, Apple argued the Board misconstrued the claims to require that the mobile computer send the secure message directly to the intermediate computer. Rather, Apple asserted, the mobile computer need not send the message to the first network address so long as the message is sent there eventually. Specifically, Apple emphasized that the PTAB’s construction is inconsistent with the phrase “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” in claim 1 of the ’494 patent, upon which claim 11 depends.

The Court construed the plain meaning of “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” requires the mobile computer to send the message to the first network address. The phrase identifies the sender (i.e., the mobile computer) and the destination (i.e., the first network address). The CAFC maintained that the proximity of the concepts links them together, such that a natural reading of the phrase conveys the mobile computer sends the secure message to the first network address. Thus the CAC agreed with the PTAB that the plain language establishes direct sending.

The Court reenforced their holding by looking to the written description as confirming this plain meaning. Specifically, they noted it describes how the mobile computer forms the secure message with “the destination address . . . of the intermediate computer.” The mobile computer then sends the message to that address. There is no passthrough destination address in the intermediate computer that the secure message is sent to before the first destination address. Accordingly, like the claim language, the written description describes the secure message as sent from the mobile computer directly to the first destination address.

Second, the CAFC examined dependent claim 4 of the ’494 patent is similar to claim 5 of the ’362 patent. Claim 4 of the ‘494 recites:

…wherein the translation table includes two partitions, the first partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the secure message is sent to the first network address, the second partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the forwarded encrypted data payload is sent to the destination address. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board had interpreted “information fields” in this claim to require “two or more fields.” However, Apple’s obviousness argument relied on Figure 21 of Grabelsky, which disclosed a partition with only a single field. Therefore, the Board found Apple failed to show the combination taught this limitation. Moreover, the Board found Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the combination to use multiple fields.

On claim construction, Apple contended there is a presumption that a plural term covers one or more items. Apple maintained that patentees can overcome that presumption by using a word, like “plurality”, that clearly requires more than one item.

The Court found that Apple misstated the law. In accordance with common English usage, the Court presumes a plural term refers to two or more items. And found that this is simply an application of the general rule that claim terms are usually given their plain and ordinary meaning.

The Court also noted that there is nothing in the written description providing any significance to using a plurality of information fields in a partition. The CAFC therefore found that absent any contrary intrinsic evidence, the Board correctly held that fields referred to more than one field.

Third, the Court looked to Claim 2 of the ’494 patent and claim 3 of the ’362 patent. Claim 2 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is further configured to substitute the unique identity read from the secure message with another unique identity prior to forwarding the encrypted data payload. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board construed the word “substitute” to require “changing or modifying, not merely adding to.” Because it determined that RFC3104 merely involved “adding to” the unique identity, the Board found Apple had failed to show RFC3104 taught this limitation. The Board expressly addressed Apple’s argument from the hearing that “adding the header is the same as replacing the header because at the end of the day you have a different header than what you had before, a completely different header.” The Board disagreed with Apple and construed “substitute” to mean “changing, replacing, or modifying, not merely adding,” and observed that this construction disposed of Apple’s position.

The CAFC found no misconstruction by the PTAB with this interpretation. Moreover, the Court noted tat substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding that Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the prior art combination to include substitution. Apple relied solely on its expert’s contrary testimony, which the Court found the Board had properly disregarded as conclusory.

Fourth, the Court reviewed the PTAB’s interpretation of claim 9 of the ’494 patent, similar to claim 10 of the ’362 patent. Claim 9 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is configured to modify the translation table entry address fields in response to a signaling message sent from the mobile computer when the mobile computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the mobile computer is changed. (emphasis added in opinion).

Apple argued that establishing a secure authorization in RFC3104 includes creating a new table entry address field as required by the claim. The Board disagreed, reasoning that “modify[ing] the translation table entry address fields” requires having existing address fields when the mobile computer changes its address. Accordingly, it found Apple failed to how the combination taught this limitation. Apple argued before the CAFC that the “configured to modify the translation table entry address fields” limitation is purely functional and, thus, covers any embodiment that results in a table with different address fields, including new address fields. The CAFC disagreed, finding as the Board held, the plain meaning of “modify[ing] the translation table entry address fields” requires having existing address fields in the translation table to modify.

Specifically, the Court reasoned that the surrounding language showing the modification occurs “when the mobile computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the mobile computer is changed” further supports the existence of an address field prior to modification. Thus, the CAFC found that the limitation does not merely claim a result; it recites an operation of the intermediate computer that requires an existing address field.

Fifth and final, the Court reviewed claim 7 of the ’502 patent which recites:

…wherein the computer is configured to send a signaling message to the intermediate computer when the computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the computer is changed.

The Court noted that the RFC3104 disclosed an ASSIGN_REQUEST_RSIPSEC message that requests an IP address assignment. Apple argued that, when a computer moves to a new address, the computer uses this message as part of establishing a secure connection and, in the process, the intermediate computer knows the address has been changed. The Board had found that the message was not used to signal address changes. Accordingly, the Board determined that Apple had failed to show that the intermediate computer knows that the address is changed, as required by the claim language. Apple reprises its arguments, which the Board had rejected.

The CAFC noted that claims 7–9 of the ’502 patent require a computer to send a message to the intermediate computer “such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the computer is changed.” The Court affirmed the Board’s contrary finding was supported by substantial evidence, including MPH’s expert testimony and RFC3104 itself. MPH’s expert testified that a skilled artisan would not have understood the relevant disclosure in RFC3104 to teach any signal address changes. Agreeing with the PTAB, the Court found that the relevant disclosure in RFC3104 relates to establishing an RSIP-IPSec session, not to signal address changes. Hence, they saw no reason why the Board was required to equate communicating a new address and signaling an address change. They therefore concluded that substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding.

In the end, the CAFC affirmed all of the Board’s final written decisions holding that claims 2, 4, 9, and 11 of the ’494 patent; claims 7–9 of the ’502 patent; and claims 3, 5, 10, and 12–16 of the ’362 patent would not have been obvious.

Take away:

Although the CAFC reviews claim construction and the Board’s legal conclusions of obviousness de novo, they are inclined toward giving deference to the PTAB. Caution should be taken in attempting to convince the CAFC that the Board has misconstrued claims unless there is a clear showing that the Board did not follow the Phillips standard (Claim terms are given their plain and ordinary meaning, which is the meaning one of ordinary skill in the art would ascribe to a term when read in the context of the claim, specification, and prosecution history).

Winning on Objective Indicia of Non-Obviousness in an IPR

| March 11, 2022

Quanergy Systems, Inc.. v. Velodyne Lidar USA, Inc.

Opinion by: O’Malley, Newman, and Lourie

Decided on February 4, 2022

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s validity decisions in two IPRs for Velodyne’s patent on lidar, relying substantially on Velodyne’s objective evidence of non-obviousness. Quanergy’s appeal attacked the PTAB’s presumption of a nexus between Velodyne’s product and the claimed invention. In particular, Quanergy challenged the nexus presumption by arguing that there were unclaimed features that attributed to the significance of Velodyne’s products, instead of the claimed invention. The Federal Circuit found the PTAB’s reasoning for how each alleged unclaimed feature resulted directly from claim limitations – such that Velodyne’s products are essentially the claimed invention – were found to be both adequate and reasonable.

Procedural History:

Quanergy Systems, Inc. (Quanergy) challenged the validity of Velodyne Lidar USA, Inc. (Velodyne) U.S. Patent 7,969,558 in two inter partes review (IPR) proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) as being obvious. The PTAB sustained the validity of the ‘558 patent. The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision.

Background:

The ‘558 patent relates to a lidar-based 3-D point cloud measuring system, useful in autonomous vehicles. “Lidar” is an acronym for “Laser Imaging Detection and Ranging.” Lidar technology uses a pulse of light to measure distance to objects. Each pulse of light for measurement results in one “pixel” and a collection of pixels is called a “point cloud.” A 3-D point cloud may be achieved by making measurements with the light pulses in up-down directions, as well as in 360 degrees. Representative claim 1 is as follows:

A lidar-based 3-D point cloud system comprising:

a support structure;

a plurality of laser emitters supported by the support structure;

a plurality of avalanche photodiode detectors supported by the support structure; and

a rotary component configured to rotate the plurality of laser emitters and the plurality of avalanche photodiode detectors at a speed of at least 200 RPM.

Quanergy relied on a Mizuno reference that uses a “triangulation system” measuring the distance to an object by detecting light reflected from the object to image sensors. Quanergy also relied on a Berkovic reference that teaches the triangulation technique, as well as a time-of-flight sensing technique. To win on obviousness, Quanergy relied on a broad interpretation of “lidar” to encompass both triangulation systems and “pulsed time-of-flight (ToF) lidar.”

However, the PTAB construed “lidar” to mean pulsed time-of-flight lidar because the ‘558 specification exclusively focuses on pulsed time-of-flight lidar in which distance is measured by the “time” of travel (i.e., flight) of the laser pulse to and from an object. The PTAB also found that Mizuno does not address a time-of-flight lidar system. Instead, Mizuno’s triangulation system is a short-range measuring device. And, the PTAB held that the skilled artisan would not have had a reasonable expectation of success in modifying Mizuno’s device to use pulsed time-of-flight lidar because Quanergy’s expert did not explain how or why a skilled artisan would have had an expectation of success in overcoming the problems in implementing a pulsed time-of-flight sensor in a short range measurement system such as that of Mizuno’s. Indeed, the Berkovic reference was found to suggest that the accuracy of pulsed time-of-flight lidar measurements degrades in shorter ranges, such as in Mizuno’s system.

But, more importantly, the PTAB relied substantially on Velodyne’s objective evidence of non-obviousness, which “clearly outweighs any presumed showing of obviousness by Quanergy” even if Quanergy satisfied obviousness with respect to the first three of the four Graham v John Deere factors (i.e., (1) scope and content of the prior art, (2) difference between the prior art and the claims at issue, (3) level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art, and (4) any objective indicia of nonobviousness).

Decision:

As for the initial claim construction issue regarding “lidar,” the Federal Circuit agreed with the strength of the intrinsic record focusing exclusively on pulsed time-of-flight lidar, collecting time-of-flight measurements, and taking note of the specification’s boasted ability to “collect approximately 1 million time of flight (ToF) distance points per second, overcoming commercial point cloud systems inability to meet the demands of autonomous vehicle navigation. Indeed, the court found Quanergy’s arguments for a broader construction to be inconsistent with the specification and therefore unreasonable.

Quanergy also challenged the PTAB’s presumption of a nexus between the claimed invention and Velodyne’s evidence of an unresolved long-felt need, industry praise, and commercial success.

To accord substantial weight to Velodyne’s objective evidence, that evidence must have a “nexus” to the claims, i.e., there must be a “legally and factually sufficient connection” between the evidence and the patented invention.

The Federal Circuit may presume a nexus to exist “when the patentee shows that the asserted objective evidence is tied to a specific product and that product ‘embodies the claimed features, and is co-extensive with them.” This co-extensiveness does not require a patentee to prove perfect correspondence between the product and the patent claim. Instead, it is sufficient to demonstrate that “the product is essentially the claimed invention.” In this analysis, “the fact finder must consider the unclaimed features of the stated products to determine their level of significance and their impact on the correspondence between the claim and the products.” “Some unclaimed features ‘amount to nothing more than additional insignificant features,’ such that presuming nexus is still appropriate.” “Other unclaimed features, like a ‘critical’ unclaimed feature that is claimed by a different patent and that materially impacts the product’s functionality, indicate that the claim is not coextensive with the product.”

This presumption of a nexus is rebuttable. However, a patent challenger may not rebut the presumption of nexus with argument alone. The patent challenger may present evidence showing that the proffered objective evidence was “due to extraneous factors other than the patented invention” such as unclaimed features or external factors like improvements in marketing or superior workmanship.

Here, Quanergy argued that the PTAB failed to consider the issue of unclaimed features before presuming a nexus and failed to provide an adequate factual basis or reasoned explanation dismissing the unclaimed features argument. Quanergy argued that Velodyne’s evidence relies on unclaimed features, including high frame-rate, dense 3D point cloud with a wide field of view and collecting measurements in an outward facing lidar for 360 degree azimuth and 26 degree vertical arc. And, such unclaimed features are critical and materially impact the functionality of Velodyne’s products. Therefore, the requisite presumption of a nexus does not exist.

However, the court found that the PTAB considered, and adequately/reasonably did so, the unclaimed features arguments, reasonably finding that Veloydyne’s products embody the full scope of the claimed invention and that the claimed invention is not merely a subcomponent of those products. First, the PTAB credited Velodyne’s expert testimony providing a detailed analysis mapping claim 1 to description of Velodyne’s product literature. Second, the claims call for a 3-D point cloud and the density of the cloud and the 360 degree horizontal field of view (i.e., the ”unclaimed features”) “result directly” from the limitation for “[rotating] the plurality of laser emitters and the plurality of avalanche photodiode detectors at a speed of at least 200 RPM.” The “3-D” feature necessarily infers both horizontal and vertical fields of view. The PTAB also pointed to (1) contemporaneous news articles describing the long-felt need for a lidar sensor that could capture points rapidly in all directions and produce a sufficiently dense 3-D point cloud for autonomous navigation, (2) articles praising Velodyne as the top lidar producer and Velodyne’s products, and (3) financial information and articles reflecting Velodyne’s revenue and market share to show commercial success.

The court also found the PTAB’s analysis of those unclaimed features arguments to be commensurate with Quanergy’s presentation of the issue. Here, the court found Quanergy’s unclaimed features arguments to be merely skeletal, undeveloped arguments. In contrast, the PTAB’s explanation of how each alleged unclaimed feature results directly from claim limitations – such that Velodyne’s products are essentially the claimed invention – were found to be both adequate and reasonable.

Quanergy also presented new arguments (not previously presented to the PTAB) that, to obtain the dense 3-D point cloud, Velodyne’s products require the unclaimed critical features of (1) more than 2 laser emitters, (2) a high pulse rate, (3) vertical angular separation between pairs of emitters and detectors, and (4) a rotation speed significantly greater than 200 RPM. However, the court held that these new arguments, presented only on appeal, were forfeited.

Takeaways:

- This case is a good primer for how to best present or attack objective indicia of non-obviousness.

- One key to success for objective indicia of non-obviousness is expert testimony mapping claimed features to product literature and explaining how and why that description of the product is essentially the claimed invention. Other helpful evidence includes contemporaneous news articles about the long-felt need, praise for the subject product, and financial information/articles showing the company’s commercial success, presumably tied to the subject product.

- If unclaimed features are asserted to attack a presumption of nexus, expert testimony explaining how those alleged unclaimed features are direct results from claimed limitations, so as to side step the attack, is helpful.

- Skeletal arguments are insufficient. If making an unclaimed features argument, it is best to flesh it out before the PTAB in detail, otherwise it will be considered forfeited if newly presented on appeal.

BREATHE EASIER, THE CAFC PROVIDES GUIDANCE ON CONSTRUING THE CLAIMED CONCENTRATION OF A STABILIZER IN PATENTS FOR AN ASTHMA DRUG

| February 25, 2022

AstraZeneca v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals

Decided December 8, 2021

Taranto, Hughes, and Stoll. Opinion by Stoll. Dissent by Taranto

Summary:

AstraZeneca sued Mylan for infringement of its patents covering Symbicort pressurized metered-dose inhaler (pMDI) which is used for treating asthma. At issue in this case is how to construe the limitation “PVP K25 is present at a concentration of 0.001% w/w.” The district court construed the concentration using the ordinary standard scientific convention using only one significant figure to encompass the range from 0.0005% to 0.0014%. Based on this construction, Mylan stipulated to infringement. The district court then held a trial on validity and upheld the validity of the asserted claims. The CAFC affirmed the district court’s judgment of validity. But the CAFC disagreed with the construction of the concentration limitation. The CAFC held that the construction of the term should be narrower than the range provided by the ordinary meaning due to disclosures in the specification and arguments and amendments in the prosecution history. The CAFC construed the noted concentration of 0.001% to include the narrower range of 0.00095% to 0.00104%. Thus, the CAFC vacated the judgment of infringement and remanded for further proceedings on infringement.

Details:

The patents at issue in this case are U.S. Patent Nos. 7,759,328; 8,143,239; and 8,575,137 which cover the asthma inhaler Symbicort pMDI. A pMDI inhaler uses a propellant gas that is in liquid form under pressure in the pMDI device. When the inhaler is activated, the propellant causes the gas to come out as a spray making it easier to deliver the medication to the lower lungs. The representative claim is provided:

13. A pharmaceutical composition comprising

formoterol fumarate dihydrate, budesonide, HFA227, PVP K25, and PEG-1000,

wherein the formoterol fumarate dihydrate is present at a concentration of 0.09 mg/ml,

the budesonide is present at a concentration of 2 mg/ml,

the PVP K25 is present at a concentration of 0.001% w/w, and

the PEG-1000 is present at a concentration of 0.3% w/w.

Mylan appealed the district court’s stipulated judgment of infringement asserting that the district court erred in the construction of the concentration of PVP K25 of 0.001%. Mylan also appealed the district court judgement of nonobviousness.

The CAFC stated that as a matter of standard scientific convention, the noted concentration of 0.001% being expressed with only one significant digit would ordinarily encompass a range from 0.0005% to 0.0014%. AstraZeneca argued that this ordinary meaning controls absent lexicography or disclaimer. However, the CAFC stated that this is an acontextual construction that does not consider disclosures in the specification and arguments/amendments in the prosecution history. The CAFC stated that “[c]onsistent with Phillips, therefore, we must read the claims in view of both the written description and prosecution history.”

The CAFC stated that the testing evidence in the specification and prosecution history demonstrates that minor differences as small as ten thousandths of a percentage (four decimal places) in the concentration of PVP impact stability. The specification repeatedly describes formulations containing 0.001% PVP as providing the best suspension stability. This is also demonstrated in the data provided in the specification. The data includes formulations including PVP at concentrations of 0.0001%, 0.0005%, 0.001%, 0.01%, 0.03%, and 0.05%. The results show that the formulation containing 0.001% PVP was the most stable and that the formulation containing 0.0005% was one of the least stable formulations. The CAFC concluded that this data shows that PVP concentration of 0.001% is more stable than formulations with slight differences in PVP concentration (e.g., a concentration of 0.0005%, and that differences down to the ten-thousandth of a percentage (fourth decimal place) matters for stability.

In the prosecution history, the Applicant amended the claims to change ranges of the concentration to recite the exact concentration of PVP to 0.001% without using the qualifier “about,” and emphasized that 0.001% was critical to stability. The CAFC also stated that Applicant knew how to claim ranges and describe numbers with approximation using the term “about,” but the Applicant chose to claim the exact value. The CAFC concluded that this supports construing 0.001% narrowly, but that there should be some room for experimental error in the PVP concentration. The CAFC stated that the margin of error that is best supported by the intrinsic record is variations in the PVP concentration at the fourth decimal place (0.000095% to 0.000104%).

AstraZeneca argued that Mylan’s proposed construction is an attempt to limit the scope of the claims to the preferred embodiment. However, the CAFC stated that AstraZeneca’s proposed construction would read on two distinct formulations described in the specification (0.0005% PVP and 0.001% PVP), but the Applicant chose to claim only one of these formulations. The CAFC also stated that Applicant cancelled claims that included the 0.0005% PVP concentration and that this provides evidence that the formulations containing 0.0005% PVP are not within the scope of an asserted claim.

Regarding the nonobviousness determination by the district court, Mylan argued that the district court erred in finding that the prior art reference Rogueda taught away from the claimed invention. The CAFC citing Meiresonne v. Google, Inc., 849 F.3d 1379 (Fed Cir. 2017), stated that “a prior art reference is said to teach away from the claimed invention if a skilled artisan ‘upon reading the reference, would be discouraged from following the path set out in the reference, or would be led in a direction divergent from the path that was taken’ in the claim.”

The Rogueda reference included control formulations to compare with its novel formulations. Mylan relied on some of the control formulations as rendering the claims obvious. Rogueda disclosed that the novel formulations provided a “drastic” reduction in the amount of drug adhesion compared to the controls.

Mylan, citing Meiresonne, argued that the court’s precedent regarding “teaching away” is that a reference “that merely expresses a general preference for an alternative invention but does not criticize, discredit, or otherwise discourage investigation into the claimed invention does not teach away.” Mylan argued that Rogueda merely expresses a preference for the novel formulations over the control formulations citing a statement in the district court opinion that “Rogueda did not necessarily disparage the formulations in Controls 3 and 9.” However, AstraZeneca provided expert testimony stating that a skilled artisan looking at the adhesion results in Rogueda would conclude that the control formulations “were not suitable” and “clearly don’t work.” The district court credited the expert testimony that a skilled artisan would have known that the control formulations were unsuitable, and thus, discouraging investigation into these formulations, and concluded that Rogueda teaches away and does not render the claims obvious. The CAFC stated that there was no clear error in the district court’s determination and affirmed the validity of the claims.

Dissent

Judge Taranto dissented from the claim construction opinion. Judge Taranto stated that 0.001% should be construed to have its significant-figure meaning of 0.0005% to 0.0014% with the possibility of shrinking the lower end of the range to exclude the overlap area between the significant-figure interval of 0.001% (0.0005% to 0.0014%) and the significant-figure interval of 0.0005% (00045% to 0.00054%). Thus, if this exclusion is applied, the range would be 0.00055% to 0.0014%.

Judge Taranto takes the position that nothing in the specification or prosecution history warrants departing from the ordinary meaning. Judge Taranto pointed out that the specification, when referring to the formulations that were tested, states that several of the formulations were “considered excellent” and that the formulation with 0.001% PVP “gave the best suspension ability overall.” In the prosecution history, the Examiner stated the need for the Applicant to show criticality by showing unexpected results of a 0.001% concentration level compared to concentration levels “slightly greater or less” than 0.001% PVP. But it is unclear if the Examiner meant to include 0.0005% and other tested concentration levels tested within the meaning of “slightly greater or less.” The Examiner’s statement about criticality does not exclude 0.0005%.

Judge Taranto also stated that changing “0.001%” having one significant figure to “0.0010%” having two significant figures (as proposed by Mylan and adopted by the majority) requires rewriting the claim term, and that this rewriting is counter to the specification and prosecution history. The specification and prosecution history uniformly used only one significant figure when referring to PVP concentration. Just because four decimal places were used for some PVP concentrations does not mean that all concentration values should be read to express a degree of precision to four decimal places. The specification uses four decimal places to refer to the absolute concentration level in examples where this is unavoidable such as for 0.0001% and 0.0005%. However, absolute levels and degrees of precision are distinct.

Judge Taranto also addressed the fact that the range implied by 0.001% overlaps the range implied by 0.0005%. Judge Taranto stated that the overlap does not support adding an extra significant digit. Judge Taranto stated that “the most this overlap could possibly support would be an exclusion of the small range with the one significant-figure interval for which there is overlap resulting in the range of 0.00055% to 0.0014%. However, Judge Taranto pointed out that Mylan’s product is still within this narrower range, and thus, it is not necessary to decide whether the overlap-area exclusion is justified as a claim construction.

Comments

The majority appears to have been swayed by the fact that a formulation within the range of the ordinary meaning of the claimed concentration provided significantly different results. What is not clear is whether these different results, while not the best, could still be considered good. Judge Taranto pointed out that the specification stated that several of the tested formulations were considered excellent while the 0.001% was the best. When drafting and prosecuting patent applications, you need to be aware that your experimental data and amendments to the claims can be used to narrow the range afforded by the ordinary meaning of a certain value.

With regard to arguing non-obviousness due to a teaching away in the prior art, expert testimony can be critical and should be used to support your argument whether you are defending the validity of a patent or trying to invalidate.

Lets’ B. Cereus, No Reasonable Fact Finder Could Find an Expectation of Success Based on the Teachings of a Prior Art Reference That Failed to Achieve That Which The Inventor Succeeds

| December 6, 2021

University of Strathclyde vs., Clear-Vu Lighting LLC

Circuit Judges Reyna, Clevenger and Stoll (author).

Summary:

Here, the University of Strathclyde (Strathclyde herein after) appeals from a final written decision of the Patent Trail and Appeal Board holding claims 1 to 4 of U.S. Patent No. 9,839,706 unpatentable as obvious.

The patent relates to effective sterilization methods for environmental decontamination of air and surfaces of, amongst other antibiotic resistant Gram-positive bacteria, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Specifically, sterilization is performed via photoinactivation without the need for a photosensitizing agent.

Claim 1[1] is as follows:

1. A method for disinfecting air, contact surfaces or materials by inactivating one or more pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria in the air, on the contact surfaces or on the materials, said method comprising exposing the one or more pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria to visible light without using a photosensitizer, wherein the one or more pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria are selected from the group consisting of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus (CONS), Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Clostridium species, and wherein a portion of the visible light that inactivates the one or more pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria consists of wavelengths in the range 400-420 nm, and wherein the method is performed outside of the human body and the contact surfaces or the materials are non-living.

The Board determined that claim 1 above would have been obvious over Ashkenazi in view of Nitzan. Ashkenazi is an article that discusses photoeradication of a Gram-positive bacterium, stating that “In the case of P. acnes (leading cause of acne) or other bacterial cells that produce porphyrins…. Blue light may photoinactivate the intact bacterial cells.” However, as noted by the CAFC, the methods of Ashkenazi always contained a photosensitive agent. Ashkenazi taught that increasing the light doses, the number of illuminations, and the length of time the bacteria are cultured resulted in greater inactivation.

The Nitzan article studied the effects of ALA (photosensitive agent) on Gram-positive bacteria, including MRSA. In Nitzan, for all the non-ALA MRSA cultures, it was reported therein that a 1.0 survival fraction was observed, meaning there was “no decrease in viability…after illumination” with blue light.

The Board ultimately held that Ashkenazi and Nitzan taught or suggested all the limitations of claim 1, and that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to combine these two references, and “would have had a reasonable expectation of successfully doing so.”