IPR Amendments: Broader is Broader (even narrowly so).

| September 15, 2023

Sisvel International S.A. v. Sierra Wireless, Inc, Telit Cinterion Deuschland GMBH

Decided: September 1, 2023

Before Prost, Reyna and Stark. Authored by Stark.

Summary: Sisvel appealed a PTAB IPR decision based on claim construction and denial of entry of a claim amendment for broadening the claim. The CAFC affirmed the Board on both counts, noting that broad disclosures in the specification will lead to a broad interpretation of the claims, and that claim amendments which encompass embodiments that would come within the scope of the amended claim but would not have infringed the original claim will be considered broadening.

Background:

In an IPR involving Sisvel’s patent claims 10, 11, 13, 17, and 24 of U.S. Patent No. 7,433,698 (the “’698 patent”) and claims 1, 2, 4, and 13-18 of U.S. Patent No. 8,364,196 (the “’196 patent”), the PTAB had found all claims unpatentable as anticipated and/or obvious in view of certain prior art.

The issues centered on the phraseology in the claims regarding the “connection rejection message” being used to direct a mobile communication means to attempt a new connection with certain parameter values such as a certain carrier frequency.

Claim 10, reproduced below, was the primary representative claim used by the CAFC:

10. A channel reselection method in a mobile communication means of a cellular telecommunication system, the method comprising the steps of:

receiving a connection rejection message;

observing at least one parameter of said connection rejection message; and

setting a value of at least one parameter for a new connection setup attempt based at least in part on information in at least one frequency parameter of said connection rejection message.

On appeal, Sisvel challenged the Board’s construction of the single claim term, “connection rejection message.”

Sisvel also challenged the Board’s denial of their motion to amend the claims on the basis that the amendment enlarged their scope.

Decision:

(a) Claim construction of “connection rejection message”

Sisvel appealed the Board’s construction of giving “connection rejection message” its plain and ordinary meaning of “a message that rejects a connection.” Sisvel’s purported a construction of “a message from a GSM or UMTS telecommunications network rejecting a connection request from a mobile station.” However, the PTAB found that such a construction would improperly limit the claims to embodiments using a Global System for Mobile Communication (“GSM”) or Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (“UMTS”) network.

Sisvel argued that UMTS and GSM “are the only specific networks identified by [the] ’698 and ’196 patents that actually send connection rejection messages” provided for in their specification.

The CAFC, in required fashion, reiterated the Phillips claim-construction standard – whereby “[t]he words of a claim are generally given their ordinary and customary meaning as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art when read in the context of the specification and prosecution history,” citing Thorner v. Sony Comput. Ent. Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (citing Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc)) 669 F.3d at 1365.

After reviewing, the Court found that the intrinsic evidence provided no persuasive basis to limit the claims to any particular cellular networks. They noted that the specification, while only expressly disclosing embodiments in a UMTS or GSM network, in fact still included broad teachings directed to any network. The CAFC affirmed the Board, noting that a person of ordinary skill in the art would not read the broad claim language, accompanied by the broad specification statement to be limited to GSM and UMTS networks.

(b) IPR Amendment

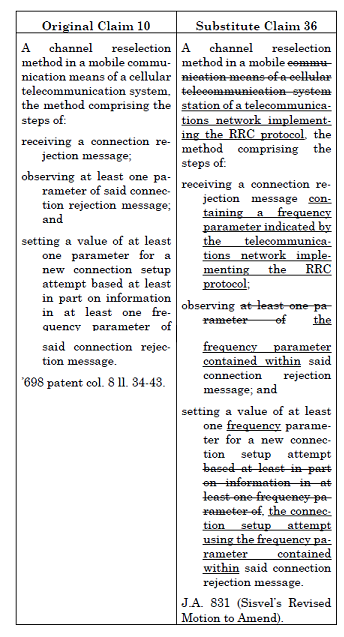

The Court also considered Sisvel’s contention that the Board erred during the IPR by denying its motion to amend the claims of the ’698 patent. The Board had denied Sisvel’s motion, concluding that the amendments to original claim 10 would have impermissibly enlarged claim scope. Original claim 10 and substitute amended claim 36 read as follows:

The Court first noted that broadening claims are not allowable during an IPR in the same fashion as in a Reissue or Reexamination proceeding at the USPTO. They further delved into the law of what constitutes a broadening of a claim noting that a claim “is broader in scope than the original claim if it contains within its scope any conceivable apparatus or process which would not have infringed the original patent” citing Hockerson-Halberstadt, Inc. v. Converse Inc., 183 F.3d 1369, 74 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

The Court further remarked that it is Sisvel’s burden, as the patent owner, to show that the proposed amendment complies with relevant regulatory and statutory requirements, citing to 37 C.F.R. § 42.121(d)(1) (“A patent owner bears the burden of persuasion to show, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the motion to amend complies with the [applicable] requirements . . . .”).

The PTAB’s denial had focused on the last (“setting a value”) limitation, comparing the original claim’s requirement that the value be set “based at least in part on information in at least one frequency parameter” of the connection rejection message, while in the substitute claims the value may be set merely by “using the frequency parameter” contained within the connection rejection message. The Board had concluded that “[i]n proposed substitute claim 36, the value that is set need not be based, in whole or in part, on information in the connection rejection message and, thus, claim 36 is broader in this respect than claim 10.” J.A. 73.

The Court agreed with the PTAB’s reasoning that, in the context of these claims, “using” is broader than “based on” and that whereas the original claim language required that the value in a new connection setup attempt be at least in some respect impacted by (i.e., “based” on) the frequency parameter, the substitute claim removes this requirement. They concluded that this removal of a claim requirement can broaden the resulting amended claim, because it is conceivable there could be embodiments that would come within the scope of substitute claim 36 but would not have infringed original claim 10, citing Pannu v. Storz Instruments, Inc., 258 F.3d 1366, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (“A reissue claim that does not include a limitation present in the original patent claims is broader in that respect.”).

Take aways:

- The Phillips standard is reiterated with the Court finding that even general disclosures within a specification (i.e. not supported by any embodiments) will provide sufficient intrinsic evidence that a skilled artisan will be considered to interpret the claim language to encompass the general disclosures.

- Drafting claim amendments in a post-grant proceeding at the USPTO must be done with extreme care. Any logically conceivable interpretation of the amendment whereby embodiments would come within the scope of substitute claim but would not have infringed the original claim will be considered broadening.

CAFC splits the difference between VLSI and Intel on Claim Construction

| December 28, 2022

VLSI Technology LLC v. Intel Corp.

Decided: November 15, 2022

CHEN, BRYSON, and HUGHES. Opinion by Bryson

Summary:

The Court affirmed the PTAB’s claim construction which had narrowed an interpretation taken from the related District Court’s construction and remanded on a separate claim construction for reading a “used for” aspect out of the claim.

Background:

Intel filed three IPR’s against VLSI’s U.S. Patent No. 7,247,552 (“the ’552 patent”). The ’552 patent is directed to the structures of an integrated circuit that reduce the potential for damage to the interconnect layers and dielectric material when the chip is attached to another electronic component. The two representative claims were claim 1 directed to a device and claim 20 directed to a method. The terms subject to construction are emphasized below.

1. An integrated circuit, comprising:

a substrate having active circuitry;

a bond pad over the substrate;

a force region at least under the bond pad characterized by being susceptible to defects due to stress applied to the bond pad;

a stack of interconnect layers, wherein each interconnect layer has a portion in the force region; and

a plurality of interlayer dielectrics separating the interconnect layers of the stack of interconnect layers and having at least one via for interconnecting two of the interconnect layers of the stack of interconnect layers;

wherein at least one interconnect layer of the stack of interconnect layers comprises a functional metal line underlying the bond pad that is not electrically connected to the bond pad and is used for wiring or interconnect to the active circuitry, the at least one interconnect layer of the stack of interconnect layers further comprising dummy metal lines in the portion that is in the force region to obtain a predetermined metal density in the portion that is in the force region.

20. A method of making an integrated circuit having a plurality of bond pads, comprising:

developing a circuit design of the integrated circuit;

developing a layout of the integrated circuit according to the circuit design, wherein the layout comprises a plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers that extend under a first bond pad of the plurality of bond pads, at least a portion of the plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers underlying the first bond pad and not electrically connected to the bond pad as a result of being used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad;

modifying the layout by adding dummy metal lines to the plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers to achieve a metal density of at least forty percent for each of the plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers; and

forming the integrated circuit comprising the dummy metal lines.

VLSI had brought suit in the District of Delaware, charging Intel with infringing the ’552 patent. The District court construed the term “force region,” referencing the specification of the ’552 patent to mean a “region within the integrated circuit in which forces are exerted on the interconnect structure when a die attach is performed.” In the IPRs Intel proposed a construction of “force region” that was consistent with that adopted by the district court and VLSI did not oppose Intel’s proposed construction before the Board.

However, in the course of the IPR proceedings it became apparent that they disagreed as to the meaning of the term “die attach” as set forth in the District court construction.

Intel argued that the term “die attach” refers to any method of attaching the chip to another electronic component, and that the term “die attach” therefore includes attachment by a method known as wire bonding. VLSI argued that the term “die attach” refers to a method of attachment known as “flip chip” bonding, and does not include wire bonding.

The construction was paramount to claim 1 as applying its proposed restrictive definition of “die attach,” VLSI distinguished Intel’s principal prior art reference for the “force region” limitation, U.S. Patent Publication No. 2004/0150112 (“Oda”). Oda discloses attaching a chip to another component using wire bonding but not the flip chip process.

The Board sided with Intel that wire bonding is a type of die attach, and that Oda therefore disclosed a “force region”. Specifically, the Board found that the ’552 patent specification made clear in several places that the term “force region” was not limited to flip chip bonding, but could include wire bonding as well. Based on that finding, the Board concluded that Oda disclosed the “force region” element of claim 1 and was unpatentable for obviousness.

Regarding claim 20 of the ’552 patent, the parties disagreed over the construction of the limitation providing that the “metal-containing interconnect layers” are “used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad.” VLSI argued that the phrase requires a connection to active circuitry or the capability to carry electricity. Intel argued that the claim does not require that the interconnection actually carry electricity.

The Board again sided with Intel, asserting the principally relied upon U.S. Patent No. 7,102,223 (“Kanaoka”) teaches the “used for electrical interconnection” limitation. The Board cited to figure 45 of Kanaoka for its disclosure of a die that has a series of interconnect layers, some of which are connected to each other.

VLSI appealed.

CAFC Decision:

VLSI argued that the Board erred in its treatment of the “force region” limitation in claim 1 and in construing the phrase “used for electrical interconnection” in claim 20 to encompass a metallic structure that is not connected to active circuitry.

Claim 1

Regarding the “force region” limitation, VLSI argued that the Board failed to acknowledge and give appropriate weight to the district court’s claim construction. In particular, VLSI based its argument principally on the requirement that the Board “consider” prior claim construction determinations by a district court and give such prior constructions appropriate weight.

However, the CAFC found that the Board was clearly well aware of the district court’s construction, as it was the subject of repeated and extensive discussion in the briefing and in the oral hearing before the PTAB. Further, the Court found that the Board did not reject the district court’s construction, but rather the district court’s construction concealed a fundamental disagreement between the parties as to the proper construction of “force region.”

They held that although the district court defined the term “force region” with reference to “die attach” processes, the district court did not decide— and was not asked to decide—whether the term “die attach,” as used in the patent, included wire bonding or was limited to flip chip bonding. Thus, the CAFC found that the Board addressed an argument not made to the district court, and it reached a conclusion not at odds with the conclusion reached by the district court.

In reaching their decision, the Court noted that other language in the specification of the ‘552 patent indicates that the claimed “force region” is not limited to attachment processes that use flip chip bonding. Restating precedence that claims should not be limited “to preferred embodiments or specific examples in the specification,” they emphasized that even if the term “die attach,” was used in one section of the specification to refer to flip chip bonding in particular other portions of the specification did make clear that the invention was not intended to be limited to flip chip bonding.

VLSI further contended that defining “force region” to mean a region at least directly under the bond pad is legally flawed because the definition restates a requirement that is already in the claims. The Court noted that although caselaw has emphasized redundant construction should not be used, in this case intrinsic evidence makes it clear that the “redundant” construction is correct. Specifically, they stated that the “force region” limitation is best understood as containing a definition of the force region, (“… just as would be the case if the language of the limitation had read ‘a region, referred to as a force region, at least under the bond pad . . .’ or ‘a force region, i.e., a region at least under the bond pad . . . .’), and concluded that the language “is best viewed not as redundant, but merely as clumsily drafted.”

Additionally, VLSI argued the Board was bound by the district court’s and the parties’ agreed upon claim construction, regardless of whether the construction to which the parties agree is actually the proper construction of that term, citing the Supreme Court’s decision in SAS Institute v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct. 1348 (2018), and the CAFC’s decisions in Koninklijke Philips N.V. v. Google LLC, 948 F.3d 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2020), and In re Magnum Oil Tools International, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

The Court rejected VLSI’s interpretation of the precedent set by the cases. Instead, they noted that each of these cases in fact stands for the proposition that the petition defines the scope of the IPR proceeding and that the Board must base its decision on arguments that were advanced by a party and to which the opposing party was given a chance to respond. They affirmatively stated that none of the relied upon cases prohibits the Board from construing claims in accordance with its own analysis and may adopt its own claim construction of a disputed claim term. Specifically, as to the case at hand, they noted the parties’ very different understandings of the meaning of the term “die attach,” and that it was clear in the Board proceedings that there was no real agreement on the proper claim construction. They conclude that in such a situation, it was proper for the Board to adopt its own construction of a disputed claim term.

Based thereon, the Court affirmed the claim construction of “force region” and the PTAB’s application of the Oda prior art reference.

Claim 20

Regarding claim 20, VLSI argued that the Board erred in construing the phrase “used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad,”. As noted above, the Board had held that this phrase encompasses interconnect layers that are “electrically connected to each other but not electrically connected to the bond pad” or to any other active circuitry. VLSI asserted that under its proposed construction, the Kanaoka reference does not disclose the “used for electrical interconnection” limitation of claim 20, because the metallic layers are connected by the vias only to one another; they do not carry electricity and are not electrically connected to any other components.

The Court agreed with VLSI that the Board’s construction of the phrase “used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad” was too broad, noting that two aspects of the claim make this point clear. First, the use of the words “being used for” in the claim imply that some sort of actual use of the metal interconnect layers to carry electricity is required. Second, the recitation of “dummy metal lines” elsewhere in claim 20 implies that the claimed “metal-containing interconnect layers” are capable of carrying electricity; otherwise, there would be no distinction between the dummy metal lines and the rest of the interconnect layer. The Court further noted that the file history of the ’552 patent and amendments made during prosecution provided additional support for this conclusion.

Furthermore, they noted that the phrase “as a result of being used for electrical interconnection not directly to the bond pad” was meant to serve some purpose and should be construed to have some independent meaning, citing Merck & Co. v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., 395 F.3d 1364, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (“A claim construction that gives meaning to all the terms of the claim is preferred over one that does not do so.”). Thus, they concluded that the words “being used for” imply that the interconnect layers are at least capable of carrying electricity.

The Court therefore remanded the patentability determination of claim 20 to the Board to assess Intel‘s obviousness arguments in light of their new construction of the “used for electrical interconnection” limitation.

Take away

The PTAB is not hamstrung by prior claim construction reached in a District Court action. The Board may construe claims in accordance with its own analysis and may adopt its own claim construction of a disputed claim term.

The recitation of an operational function (“being used for”) in a claim should not be ignored in claim construction. The claim language should be taken as a whole and other aspects of the claim (“dummy metal lines”) which infer an interpretation should be considered.

No Shapeshifting Claims Through Argument in an IPR

| December 15, 2022

CUPP Computing AS v. Trend Micro Inc.

Decided: November 16, 2022

Circuit Judges Dyk, Taranto and Stark. Opinion by Dyk.

Summary:

CUPP appeals three inter partes review (“IPR”) decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”), largely due to an issue of claim construction. The three patents at issue are U.S. Patents Nos. 8,631,488 (“’488 patent”), 9,106,683 (“’683 patent”), and 9,843,595 (“’595 patent”). The contested claim construction involves the limitation concerning a “security system processor,” which appears in every independent claim in each of the three patents.

The limitation in question reads in part “the mobile device having a mobile device processor different than the mobile security system processor”.

Trend Micro petitioned the Board for inter partes review of several claims in the ’488, ’683, and ’595 patents, arguing that the claims were unpatentable as obvious over two individual prior art references. CUPP responded that the security system processor limitation required that the security system processor be “remote” from the mobile device processor, and that neither of the cited references disclosed this limitation because both taught a security processor bundled within a mobile device.

The Board instituted review and, in three final written decisions, found all the challenged claims obvious over the prior art. Specifically, the Board held that the challenged claims did not require that the security system processor be remote from the mobile device processor, but merely that the mobile device has a mobile device processor different than the mobile security system processor.

That is, the fact that the security system processor is “different” than the mobile device processor does not suggest that the two processors are remote from one another. Rather, citing Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, the Board and the CAFC noted that the ordinary meaning of “different” is simply “dissimilar.” The CAFC further noted that CUPP had given no reason to apply a more specialized meaning to the word.

Furthermore, the CAFC drew support from the specification of each of the three Patents. Briefly, that in one “preferred embodiment” each of the patents described that the mobile security system may be incorporated within the mobile device. Thus, the CAFC concluded that “highly persuasive” evidence would be required to read claims as excluding a preferred embodiment of the invention. Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576, 1583–84 (Fed. Cir. 1996). Indeed, “a claim interpretation that excludes a preferred embodiment from the scope of the claim is rarely, if ever, correct.” Accent Pack-aging, Inc. v. Leggett & Platt, Inc., 707 F.3d 1318, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (citation omitted).

CUPP responds that, because at least one independent claim in each of the patents requires the security system to send a signal “to” the mobile device, and “communicate with” the mobile device, the system must be remote from the mobile device processor.

The CAFC were not persuaded holding that the Board properly construed the security system processor limitation in line with the specification. The CAFC analogized that “just as a person can send an email to him- or herself, a unit of a mobile device can send a signal “to,” or “communicate with,” the device of which it is a part.”

Next, CUPP argued that, because it disclaimed a non-remote security system processor during the initial examination of one of the patents at issue, the Board’s construction is erroneous. The CAFC held that the Board properly rejected that argument, because CUPP’s disclaimer did not unmistakably renounce security system processors embedded in a mobile device. Rather, the CAFC upheld the Board’s reading of CUPP’s remarks during prosecution as a “reasonable interpretation[]” that defeats CUPP’s assertion of prosecutorial disclaimer. Avid Tech., Inc., 812 F.3d at 1045 (citation omitted); see also J.A. 20–22.

Briefly, during prosecution of the ’683 patent, the Patent Office examiner found all claims in the application obvious in light of the prior art. CUPP’s responded that if the TPM “were implemented as a stand-alone chip attached to a PC mother-board,” it would be “part of the motherboard of the mobile devices” rather than being a separate processor. J.A. 3578. The TPM would therefore not constitute “a mobile security system processor different from a mobile system processor.”

The Board found, and the CAFC upheld, that under one plausible reading, CUPP’s point was that the prior art failed to teach different processors because the TPM lacks a distinct processor. Thus, under this interpretation, if the TPM were “a stand-alone chip attached to a . . . motherboard,” it would rely on the motherboard’s processor, and not have its own different processor. For this reason, the CAFC concluded that CUPP’s comment to the examiner is consistent with it retaining claims to security system processors embedded in a mobile device with a separate processor.

Lastly, CUPP contended that the Board erred by rejecting CUPP’s disclaimer in the IPRs themselves, disavowing a security system processor embedded in a mobile device.

Here, the CAFC unambiguously stated that it was making “precedential the straightforward conclusion [they] drew in an earlier nonprecedential opinion: “[T]he Board is not required to accept a patent owner’s arguments as disclaimer when deciding the merits of those arguments.” VirnetX Inc. v. Mangrove Partners Master Fund, Ltd., 778 F. App’x 897, 910 (Fed. Cir. 2019). That a rule permitting a patentee to tailor its claims in an IPR through argument alone would substantially undermine the IPR process. Congress designed inter partes review to “giv[e] the Patent Office significant power to revisit and revise earlier patent grants,” thus “protect[ing] the public’s paramount interest in seeing that patent monopolies are kept within their legitimate scope.” If patentees could shapeshift their claims through argument in an IPR, they would frustrate the Patent Office’s power to “revisit” the claims it granted, and require focus on claims the patentee now wishes it had secured. See also Oil States Energy Servs., LLC v. Greene’s Energy Grp., LLC, 138 S. Ct. 1365, 1373 (2018).

Thus, to conclude, a disclaimer in an IPR proceeding is only binding in later proceedings, whether before the PTO or in court. The CAFC emphasized that congress created a specialized process for patentees to amend their claims in an IPR, and CUPP’s proposed rule would render that process unnecessary because the same outcome could be achieved by disclaimer. See 35 U.S.C. § 316(d).

Take-away:

- A disclaimer in an IPR proceeding is only binding in later proceedings, whether before the PTO or in court.

- A claim interpretation that excludes a preferred embodiment from the scope of the claim is rarely, if ever, correct.

- Disclaimers made during prosecution must be clear and unmistakable to be relied upon later. Specifically: “The doctrine of prosecution disclaimer precludes patentees from recapturing through claim interpretation specific meanings disclaimed during prosecution.” Mass. Inst. of Tech. v. Shire Pharms., Inc., 839 F.3d 1111, 1119 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (ellipsis, alterations, and citation omitted). However, a patentee will only be bound to a “disavowal [that was] both clear and unmistakable.” Id. (citation omitted). Thus, where “the alleged disavowal is ambiguous, or even amenable to multiple reasonable interpretations, we have declined to find prosecution disclaimer.” Avid Tech., Inc. v. Harmonic, Inc., 812 F.3d 1040, 1045 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- Claim terms are given their ordinary meaning unless persuasive reason is provided to apply a more specialized meaning to the word.

Got A Lot To Say? Unfortunately, CAFC Affirm A Word Limit Will Not Prevent Estoppel Under 35 USC §315(e)(1)

| April 1, 2022

Intuitive Surgical, Inc., vs., Ethicon LLC and Andrew Hirshfeld, performing the functions and duties of the undersecretary of commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the USPTO.

Decided: February 11, 2022

Circuit Judges O’Malley (author), Clevenger and Stoll.

Summary:

The CAFC affirmed a decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal board (PTAB) terminating Intuitive’ s participation in an inter partes review (IPR) based on the estoppel provision of 35 U.S.C. §315(e)(1).

35 U.S.C. §315(e)(1) states that “[t]he petitioner in an inter partes review of a claim in a patent under this chapter that results in a final written decision . . . may not request or maintain a proceeding before the Office with respect to that claim on any ground that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review.” 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(1).

On June 14, 2018, Intuitive simultaneously filed three IPR petitions against a Patent owned by Ethicon (U.S. Patent No. 8,479,969), each challenging the patentability of claims 24 to 26 but each based upon a different combination of prior art references. Despite being filed at the same time, one of the three petitions was instituted one month after the other two. Continuing on this varied timeline, the PTAB issued final written decisions in the two petitions that instituted earliest. As a result, the PTAB found that Intuitive was estopped from participating as a party in the pending third petition. The PTAB concluded that §315(e)(1) did not preclude estoppel from applying where simultaneous petitions were filed by the same petitioner on the same claim.

Intuitive appealed. Intuitive argued that the 14000-word page limit for IPR petitions meant they could not reasonable have raised the prior art from the third and pending petition in in the same petition as the others. Intuitive argued that §315(e)(1) estoppel should not apply to simultaneously filed petitions. Intuitive argues, moreover, that it may appeal the merits of the Board’s final written decision on the patentability of the claims because, “even if the Board’s estoppel decision is not erroneous, Intuitive was once “a party to an inter partes review” and is dissatisfied with the Board’s final decision within the meaning of § 319.” (Only a party to an IPR may appeal a Board’s final written decision. See 35 U.S.C. § 141(c) (“A party to an inter partes review . . . who is dissatisfied with the final written decision . . . may appeal.”). Section 319 of Title 35 repeats that limitation).

The CAFC disagreed arguing that the plain language of §315(e)(1) is clear. §315(e)(1) estops a petitioner as to invalidity grounds for an asserted claim that it failed to raise but “reasonably could have raised” in an earlier decided IPR, regardless of whether the petitions were simultaneously filed and regardless of the reasons for their separate filing. The CAFC reasoned that since Intuitive filed all three petitions, it follows that they actually knew of all the prior art cited and so could have reasonably raised its grounds in the third petition in either of the first two petitions. First, the CAFC concludes that the petitions could have been written “more concisely” in order to fit within two petitions. Second, the CAFC noted that Intuitive had alternative avenues, including (i) seeking to consolidate multiple proceedings challenging the same patent (see 35 U.S.C. § 315(d) (permitting the Director to consolidate separate IPRs challenging the same patent)); or (ii) filing multiple petitions where each petition focuses on a separate, manageable subset of the claims to be challenged—as opposed to subsets of grounds—as § 315(e)(1) estoppel applies on a claim-by-claim basis.

Take-away:

- To avoid estoppel under 315(e)(1), when it is not possible to draft IPR petitions concisely, consider multiple petitions each focused on a separate manageable subset of claims or seek consolidation.

Forum Selection Clause Can Prevent IPR Fights

| March 25, 2022

Nippon Shinyaku Co., Ltd. v. Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc.

Decided on February 8, 2022

Lourie (author), Newman, and Stoll

Summary:

The Federal Circuit reversed the district decision’s denial of a preliminary injunction for Nippon Shinyaku because its agreement with Sarepta was clear to exclude filing IPR petitions, and Sarepta’s filing of IPR petitions clearly breached the agreement with Nippon Shinyaku.

Details:

On June 1, 2020, Nippon Shinyaku and Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc. (“Sarepta”) executed a Mutual Confidentiality Agreement (“MCA”) to enter into discussions for a potential business relationship relating to therapies for the treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (“DMD”).

Section 6 of the MCA included a mutual covenant not to sue during the Covenant Term[1]:

shall not directly or indirectly assert or file any legal or equitable cause of action, suit or claim or otherwise initiate any litigation or other form of legal or administrative proceeding against the other Party . . . in any jurisdiction in the United States or Japan of or concerning intellectual property in the field of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.

Section 6 further stated:

For clarity, this covenant not to sue includes, but is not limited to, patent infringement litigations, declaratory judgment actions, patent validity challenges before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office or Japanese Patent Office, and reexamination proceedings before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office . . . .

After the expiration of the Covenant Term, the forum selection clause in Section 10 of the MCA is applied:

[T]he Parties agree that all Potential Actions arising under U.S. law relating to patent infringement or invalidity, and filed within two (2) years of the end of the Covenant Term, shall be filed in the United States District Court for the District of Delaware and that neither Party will contest personal jurisdiction or venue in the District of Delaware and that neither Party will seek to transfer the Potential Actions on the ground of forum non conveniens.

Here, “Potential Actions” is defined as “any patent or other intellectual property disputes between [Nippon Shinyaku] and Sarepta, or their Affiliates, other than the EP Oppositions or JP Actions, filed with a court or administrative agency prior to or after the Effective Date in the United States, Europe, Japan or other countries in connection with the Parties’ development and commercialization of therapies for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.”

The Covenant Term ended on June 21, 2021, at which point the two-year forum selection took effect. On June 21, 2021, Sarepta filed seven petitions for IPR.

District Court

On July 13, 2021, Nippon Shinyaku filed a complaint in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware asserting claims against Sarepta for breach of contract, among other things. Nippon Shinyaku alleged that Sarepta breached the MCA by filing seven IPR petitions. Nippon Shinyaku filed a motion for a preliminary injunction to enjoin Sarepta from proceeding with IPR petitions.

On September 24, 2021, the district court denied Nippon Shinyaku’s motion for a preliminary injunction and issued its memorandum order with the following reasons:

- There would be a “tension” that would exist between Sections 6 and 10 if the forum selection clauses were interpreted to exclude IPRs.

- Section 10 applies only to cases filed in federal court.

- Practical effects of interpreting Section 10 as excluding IPRs for two years following the Covent Term.

- Finally, Nippon Shinyaku did not meet its burden on second (suffer irreparable harm), third (balance of hardship), fourth (public interest) PI factors in order to obtain a preliminary injunction.

Federal Circuit

The CAFC reviewed a denial of a preliminary injunction using the law of the regional circuit (Third Circuit) for abuse of discretion.

The CAFC focused on the court’s interpretation of the MCA.

Based on the plain language of the forum selection clause in Section 10 of the MCA, the CAFC held that the forum selection clause is unambiguous because the definition of “Potential Actions” includes “patent or other intellectual property disputes… filed with a court or administrative agency,” and the district court acknowledged that the definition of Potential Actions literally encompasses IPRs.

The CAFC held that under the plain language of Section 10, Sarepta should have brought all disputes regarding the invalidity of Nippon Shinyaku’s patents in the District of Delaware.

The CAFC rejected Sarepta’s argument that IPR petitions must be filed in the federal district court in Delaware. Also, the CAFC held that there is no conflict or tension between Sections 6 and 10. The CAFC noted that this reflects harmony, not tension between two sections and this framework is “entirely consistent with our interpretation of the plain meaning of the forum selection clause.”

Finally, the CAFC noted that other factors of a preliminary injunction favored Nippon Shinyaku. As for irreparable harm, the CAFC agreed with Nippon Shinyaku’s argument that they would be “deprived of its bargained-for choice of forum and forced to litigate its patent rights in multiple jurisdictions.” As for balance of hardships, Nippon Shinyaku would suffer the irreparable harm, and Sarepta would potentially get multiple chances at a forum it bargained away. As for public interest, the CAFC rejected any notion that there is “anything unfair about holding Sarepta to its bargain.”

Therefore, the CAFC reversed the decision of the district court and remanded for entry of a preliminary injunction.

Takeaway:

- Companies will need to be extra careful when drafting nondisclosure and joint development agreements now that the CAFC held that clauses in those agreements can give up right to file challenges at the PTAB.

- Contracts can be used to waive the right to AIA review.

- This is a cautionary tale for attorneys to start paying attention to boilerplate parts of contracts.

- This is the first time that the CAFC held that it is not again the public interest to have forum selection clauses that exclude PTAB proceedings.

[1] Covenant Term is defined as “the time period commencing on the Effective Date and ending upon twenty (20) days after the earlier of: (i) the expiration of the Term, or (ii) the effective date of termination.”

Tags: contract > IPR > Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) > preliminary injunction

CAFC Remands Back To PTAB Instructing Them To Conduct The Analysis And Correct The Mistakes In Wearable Technology IPR Case

| July 22, 2020

Fitbit, Inc., v. Valencell. Inc.

July 8, 2020

Before Newman, Dyk and Reyna. Opinion by Newman

Background:

Apple Inc., petitioned the Board for IPR (Inter Partes Review) of claims 1 to 13 of the U.S. Patent No., 8,923,941 (the ‘941 patent) owned by Valencell, Inc. The Board granted the petition in part, instituting review of claims 1, 2 and 6 to 13, but denying claims 3 to 5.

Fitbit then filed an IPR petition for claims 1, 2 and 6 to 13, and moved for joinder with Apple. The Board granted Fitbit’s petition and granted the motion for joinder.

After the PTAB trial, but before the Final Written Decision, the Supreme Court decided SAS Insitute, Inc., v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct 1348 (2018), holding that all patent claims challenged in an IPR petition must be reviewed by the Board, if the petition is granted. Thus, the Board re-instituted the Apple/Fitbit IPR to add claims 3 to 5.

The Board issued a Final Written Decision that held claims 1, 2 and 6 to 13 unpatentable, and claims 3 to 5 not unpatentable. Apple withdrew and Fitbit appealed the decision on claims 3 to 5. Valencell challenged Fitbit’s right to appeal claims 3 to 5.

Issues:

I. JOINDER AND RIGHT OF APPEAL

“Valencell’s position was that Fitbit did not have standing to appeal the portion of the Board’s decision that related to claims 3 to 5, because Fitbit’s IPR petition was for claims 1, 2 and 6 to 13.” Citing Wasica Finance GmbH v. Continental Automotive Systems, Inc., 853 F.3d 1272, 1285 (Fed. Cir. 2017), Valencell argued that Fitbit had “waived any argument it did not present in its petition for IPR.” That is, Valencell argued that Fitbit does not have the status of “party” for the purpose of the appeal because “Fitbit did not request review of claims 3 to 5 in its initial IPR petition.”

Fitbit countered that although it did not “seek to file a separate brief after claims 3 to 5 were added to the IPR” the briefs were not required in order to present the issues, and the CAFC agreed that the circumstances do not override Fitbit’s statutory right of appeal.

The CAFC concluded that “Fitbit’s rights as a joined party applies to the entirety of the proceeding” including the right of appeal.

II. CONSTRUCTION OF THE CLAIMS ON APPEAL

Claims 3 to 5 at issue are as follows:

3. The method of claim 1, wherein the serial data output is parsed out such that an application-specific interface (API) can utilize the physiological information and motion-related information for an application.

4. The method of claim 1, wherein the application is configured to generate statistical relationships between subject physiological parameters and subject physical activity parameters in the physiological information and motion-related information.

5. The method of claim 4, wherein the application is configured to generate statistical relationships between subject physiological parameters and subject physical activity parameters via at least one of the following: principal component analysis, multiple linear regression, machine learning, and Bland-Altman plots.

- CLAIM 3

The Board did not review patentability of claim 3 on the asserted grounds of obviousness holding that the claim is “not unpatentable” based solely on their “rejection of Fitbit’s proposed construction of the term application-specific interface (API).

Specifically, Fitbit argued that the “broadest reasonable interpretation of “application-specific interface (API)…include[s] at least an application interface that specifies how some software component should interest with each other.” Fitbit’s interpretation was based heavily on the use of “API” which followed application-specific interface. API meaning ‘application programming interface.’

Valencell argued for a narrower meaning, based upon the specification and the prosecution history. In particular, during prosecution the applicant had relied upon the narrow scope to distinguish from a cited reference.

The Board concluded the narrower claim construction was correct, and rejected Fitbit’s broader construction. The CAFC agreed with the Boards conclusion as to the correct claim construction.

However, following the Boards rejection of Fitbit’s claim construction they did not review the patentability of claim 3, as construed, on the asserted ground of obviousness. The Board explained that because “Petitioner’s assertions challenging claim 3 are based on the rejected construction…the evidentiary support relied upon is predicated upon the same” and so “[W]e do not address this claim further.”

CAFC held this was erroneous, vacated the Board’s decision and remanded for determination of patentability in light of the cited references.

- CLAIMS 4 AND 5 – ANTECEDENT BASIS OF ‘THE APPLICATION’

The Board held that claims 4 and 5 were “not unpatentable” because “the Board could not determine the meaning of the claims due to the term “the application” lacking antecedent basis.

The mistake had occurred due to the cancellation of claim 2, and erroneous renumbering of claim 4. Both Fitbit and Valencell agreed to this. Board declined to accept the parties’ shared view, stating:

Although we agree that the recitation of the term “the application” in claim 4 lacks antecedent basis in claim 1, we declined to speculate as to the intended meaning of the term. Although Petitioner and Patent Owner now seem to agree on the nature of the error in claims 4 and 5 [citing briefs], we find that the nature of the error in claims 4 and 5 is subject to reasonable debate in view of the language of claims 1 and 3–5 and/or that the prosecution history does not demonstrate a single interpretation of the claims.

The CAFC disagreed with the Board, holding that although “the Board states that the intended meaning of the claims is “subject to reasonable debate,” we perceive no debate. Rather, the parties to this proceeding agree as to the error and its correction.”

The CAFC concluded that on remand the Board shall fixed the error and determine patentability of corrected claims 4 and 5:

The preferable agency action is to seek to serve the agency’s assignment under the America Invents Act, and to resolve the merits of patentability. Although the Board does not discuss its authority to correct errors, there is foundation for such authority in the America Invents Act, which assured that the Board has authority to amend claims of issued patents. See 35 U.S.C. § 316(d). . . . The concept of error correction is not new to the Agency, which is authorized to issue Certificates of Correction.

Comments:

A joined party has full rights to appeal a PTAB final decision.

During an IPR, the Board has authority to correct mistakes in the claims of an issued patents, in particular those where a certificate of correction would be fitting.

Always, be careful when renumbering claims for antecedent issues.

Should’ve, Could’ve, Would’ve; Hindsight is as common as CDMA, allegedly!

| March 5, 2020

Acoustic Technology, Inc., vs., Itron Networked Solutions, In.

February 13, 2020

Circuit Judges Moore, Reyna (author) and Taranto.

Summary:

i. Background:

Acoustic owns U.S. Patent No., 6,509,841 (‘841 hereon), which relates to communications systems for utility providers to remotely monitor groups of electricity meters.

Back in 2010, Acoustic sued Itron for infringement of the ‘841 patent, with the parties later settling. As part of this settlement, Acoustic licensed the patent to Itron. As a result of the lawsuit, Itron was time-barrred from seeking inter partes review (IPR), of the patent. See 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).

Six years later, Acoustic sued Silver Spring Networks, Inc., (SS) for infringement, and in response, SS filed an IPR petition that has given rise to this Appeal.

Prior to and thereafter filing the IPR, SS was in discussions with Itron regarding a potential merger. Nine days after the Board instituted IPR, the parties agreed to merge. It was publicly announced the following day. The merger was completed while the IPR proceeding remained underway. SS filed the necessary notices that listed Itron as a real-party-in-interest.

Finally, seven months after Itron and SS completed the merger, the Board entered a final written decision wherein they found claim 8 of the ‘841 patent unpatentable. Acoustic did not raise a time-bar challenge to the Board.

ii. Appeal Issues:

ii-a: Acoustic alleges the Boards final written decision should be vacated because the underlying IPR proceeding is time-barred under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).

ii.b: Acoustic alleges the Boards unpatentability findings are unsupported.

iii. IPR

35 U.S.C. § 315(b)

An inter partes review may not be instituted if the petition requesting the proceeding is filed more than 1 year after the date on which the petitioner, real party in interest, or privy of the petitioner is served with a complaint alleging infringement of the patent.

The CAFC held that “when a party raises arguments on appeal that it did not raise to the Board, they deprive the court of the benefit of the Board’s informed judgment.” Thus, since Acoustic failed to raise this issue to the Board, the CAFC declined to resolve whether Itron’s pre-merger activities rendered it a real-party-in-interest. Concluding, the CAFC stated that “[A]lthough we do not address the merits of Acoustic’s time-bar argument, we note Acoustics concerns about the concealed involvement of interested, time-barred parties.”

iv. Unpatentability

The sole claim at issue is as follows:

8. A system for remote two-way meter reading comprising:

a metering device comprising means for measuring usage and for transmitting data associated with said measured usage in response to receiving a read command;

a control for transmitting said read command to said metering device and for receiving said data associated with said measured usage transmitted from said metering device; and

a relay for code-division multiple access (CDMA) communication between said metering device and said control, wherein said data associated with said measured usage and said read command is relayed between said control and metering device by being passed through said relay.

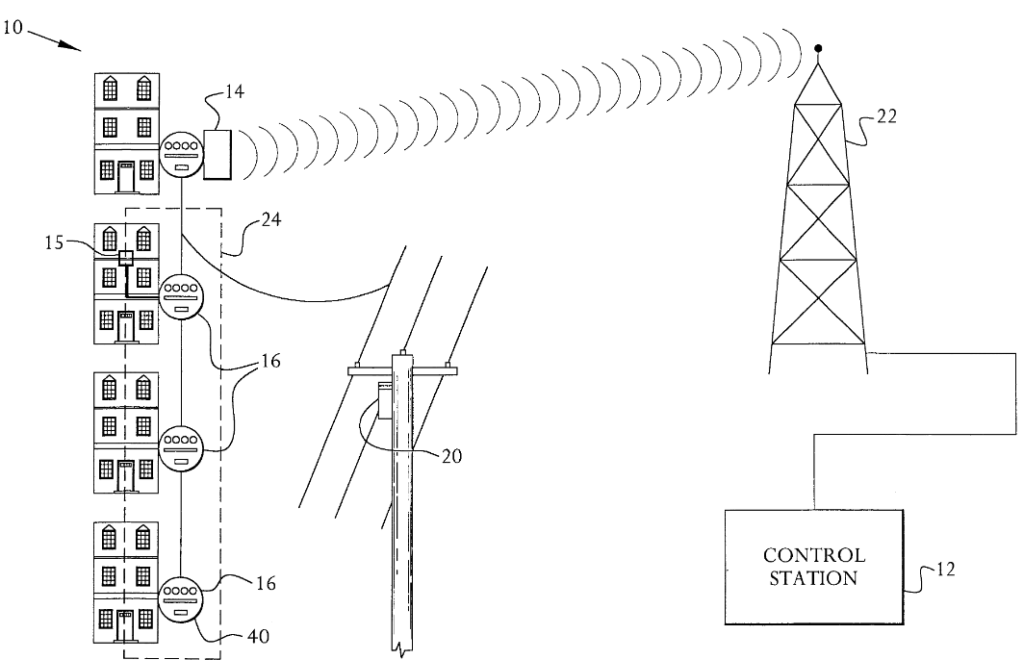

Fig. 1:

Key: 16 = on-site utility meters: 14 = relay means: 12 = contro means. The relay means can communicate via CMDA (code-divisional mutliple access), which is descibred as “an improvement upon prior art automated meter reading systems that used exspensive and problematic radio frrequency transmitter or human meter-readers.”

- Novelty

The CAFC upheld both anticipation challenges.

The first, anticipation by Netcomm, Acoustic claims that the Board erred by finding the reference disclosed the claimed CDMA communication limitation. Acoustic argued that the Board based its final decision entirely upon SS’s expert Dr. Soliman, who applied an incorrect standard. Specifically, that Dr. Soliman’s statements used the word “recognize” which, Acoustic alleged, was akin to testimony about what a prior art reference “suggests”, and so goes to obvious not anticipation. CAFC disagreed with Acoustic.

CAFC held that the “question is whether a skilled artisan would “reasonably understand or infer” from a prior art reference that every claim limitation is disclosed in that single reference.” Further that, “Expert testimony may shed light on what a skilled artisan would reasonably understand or infer from a prior art reference,” and “expert testimony can constitute substantial evidence of anticipation when the expert explains in detail how each claim element is disclosed in the prior art reference.”

The CAFC held that “Dr. Soliman conducted a detailed analysis and explained how a skilled artisan would reasonably understand that NetComm’s disclosure of radio wave communication was the same as CDMA,” and “Acoustic provided no evidence to rebut Dr. Soliman’s testimony.”

The second, anticipation by Gastouniotis, Acoustic argued that “the Board’s finding is erroneous because the Board relied on “the same structures to satisfy separate claim limitations.” Specifically, Acoustic asserts that the Board relied on the same “remote station 6” in Gastouniotis to satisfy the “control” and “relay” limitations of claim 8.” CAFC disagreed with Acoustic.

Specifically, the CAFC held that Gastouniotis disclosed a system that included a plurality of “remote stations” and “that individual “remote stations” may have different functions in a given embodiment.” So, “In finding that Gastouniotis anticipated claim 8, the Board relied on separate “remote station” structures to meet the “control” and “relay” limitations.” Again, the CAFC held that “Dr. Soliman provided unrebutted testimony that a skilled artisan would understand that these remote stations disclosed in Gastouniotis” meet the limitations of claim 8.

- Obviousness

Acoustic challenged the Boards determination of obvious in view of Nelson and Roach. “Acoustic asserts two errors in the Board’s obviousness analysis: (i) that the Board erroneously mapped Nelson onto the elements of claim 8; and (ii) that the Board’s motivation-to-combine finding is not supported by substantial evidence.” The CAFC rejected both arguments.

Regarding point (i): “Acoustic asserts that the Board relied on the same “electronic meter reader (EMR)” in Nelson to satisfy both the “metering device” and “relay” limitations of claim 8.” Again, the CAFC held that the Board had correctly relied on “separate EMR structures to meet the “metering device” and “relay” limitations,” and that “Dr. Soliman provided unrebutted testimony that a skilled artisan would recognize” the metering apparatus of Nelson as meeting the limitations of claim 8.”

Regarding point (ii): “Acoustic requests that [the CAFC] reverse the Board’s finding because the Board relied on “attorney argument,” and “generically cited to [Dr. Soliman’s] expert testimony.” The CAFC held that “The motivation to combine prior art references can come from the knowledge of those skilled in the art, from the prior art reference itself, or from the nature of the problem to be solved.” That, the CAFC “have found expert testimony insufficient where, for example, the testimony consisted of conclusory statements that a skilled artisan could combine the references, not that they would have been motivated to do so.”

However, ultimately, the CAFC found that “Dr. Soliman’s testimony was not conclusory or otherwise defective, and the Board was within its discretion to give that testimony dispositive weight.” That the Board did not merely “generically” cite to Dr. Soliman’s testimony, but cited specific pages. Thus concluding that the “expert testimony constituted substantial evidence of a motivation to combine prior art references.”

Additional Note:

The subject ‘841 Patent is a continuation of U.S. Patent Application No., 08/949,440 (Patent No., 5,986,574). Acoustic filed a related appeal in said Patent on the same day as filing this Appeal. (Acoustic Tech., Inc. v. Itron Networked Solutions, Inc., Case No. 2019-1059). Oral arguments were heard in both cases on the same day, and the CAFC simultaneously issued opinions in both cases.

In the related Appeal, Acoustics argued again that the CAFC “must vacate the Board’s final written decisions because the inter partes reviews were time-barred under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).” For the same reasons outlined above, Acoustics were unsuccessful.

The second issue on Appeal in the related case centered on Acoustic arguing that the CAFC “should reverse the Board’s obviousness findings on grounds that the Board erroneously construed the “WAN means” term.” However, the CAFC noted that “Acoustic’s argument on appeal is new. Rather than arguing that the prior art fails to disclose a conventional radio capable of transmitting over publicly available WAN, Acoustic now argues that the prior art fails to disclose any conventional WAN radio” Thus, “[B]ecause Acoustic never presented to the Board the non-obviousness arguments it now raises on appeal, we find those arguments waived,” and so the Board’s decision was affirmed.

Take-away:

1. Ensure all arguments are presented to the Board.

2. Ensure that any arguments against an unpatentability rejection directly address the actual reasons for rejection. That is, the CAFC repeatedly stated that Acoustic had failed to rebut any of the actual reasons outlined in the expert testimony that the Board ultimately relied upon in its holding.

3. Be aware of Broadest Reasonable Interpretation. Here, Acoustic argued

A Change in Language from IPR Petition to Written Decision May Not Result in A Change in Theory of Motivation to Combine

| September 25, 2019

Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Corp.

August 21, 2019

Dyk, Chen, Opinion written by Stoll

Summary

The CAFC affirmed the Board’s decision that claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541 were obvious over Gordon in view of West and that the IPR proceeding was constitutional. The CAFC held that minor variations in wording, from the IPR Petition to the written Final Decision, do not violate the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). Further, the CAFC rejected Arthrex’s argument to reconsider evidence that was contrary to the Board’s decision since there was sufficient evidence to support the Board’s findings of obviousness by the preponderance of evidence standard.

Details

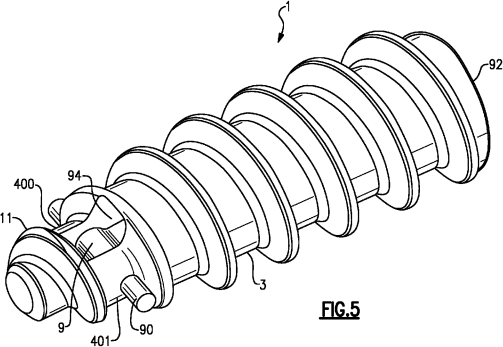

Arthrex’s Patent No. 8,821,541 (hereinafter “Patent ’541”) is directed towards a surgical suture anchor that reattaches soft tissue to bone. A feature of the suture anchor of Patent ‘541 is that the “fully threaded suture anchor’ includes ‘an eyelet shield that is molded into the distal part of the biodegradable suture anchor’”, wherein the eyelet shield is an integrated rigid support that strengthen the suture to the soft tissue. Id. at 2 and 3. The specification discloses that “because the support is molded into the anchor structure (as opposed to being a separate component), it ‘provides greater security to prevent pull-out of the suture.’ Id at col 5 ll. 52-56.” Id. at 3. Figure 5 of Patent ‘541 illustrates an embodiment of the suture anchor (component 1), wherein component 9 is the eyelet shield (integral rigid support) and component 3 is the body wherein helical threading is formed.

Claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541 are herein enclosed (emphasis added to the claim terms at issue in the dispute)

10. A suture anchor assembly comprising:

an anchor body including a longitudinal axis, a proximal end, a distal end, and a central passage extending along the longitudinal axis from an opening at the proximal end of the anchor body through a portion of a length of the anchor body, wherein the opening is a first suture opening, the anchor body including a second suture opening disposed distal of the first suture opening, and a third suture opening disposed distal of the second suture opening, wherein a helical thread defines a perimeter at least around the proximal end of the anchor body;

a rigid support extending across the central passage, the rigid support having a first portion and a second portion spaced from the first portion, the first portion branching from a first wall portion of the anchor body and the second portion branching from a second wall portion of the anchor body, wherein the third suture opening is disposed distal of the rigid support;

at least one suture strand having a suture length threaded into the central passage, supported by the rigid support, and threaded past the proximal end of the anchor body, wherein at least a portion of the at least one suture strand is disposed in the central passage between the rigid support and the opening at the proximal end, and the at least one suture strand is disposed in the first suture opening, the second suture opening, and the third suture opening; and

a driver including a shaft having a shaft length, wherein the shaft engages the anchor body, and the suture length of the at least one suture strand is greater than the shaft length of the shaft.

11. A suture anchor assembly comprising:

an anchor body including a distal end, a proximal end having an opening, a central longitudinal axis, a first wall portion, a second wall portion spaced opposite to the first wall portion, and a suture passage beginning at the proximal end of the anchor body, wherein the suture passage extends about the central longitudinal axis, and the suture passage extends from the opening located at the proximal end of the anchor body and at least partially along a length of the anchor body, wherein the opening is a first suture opening that is encircled by a perimeter of the anchor body, a second suture opening extends through a portion of the anchor body, and a third suture opening extends through the anchor body, wherein the third suture opening is disposed distal of the second suture opening;

a rigid support integral with the anchor body to define a single-piece component, wherein the rigid support extends across the suture passage and has a first portion and a second portion spaced from the first portion, the first portion branching from the first wall portion of the anchor body and the second portion branching from the second wall portion of the anchor body, and the rigid support is spaced axially away from the opening at the proximal end along the central longitudinal axis; and

at least one suture strand threaded into the suture passage, supported by the rigid support, and having ends that extend past the proximal end of the anchor body, and the at least one suture strand is disposed in the first suture opening, the second suture opening, and the third suture opening.

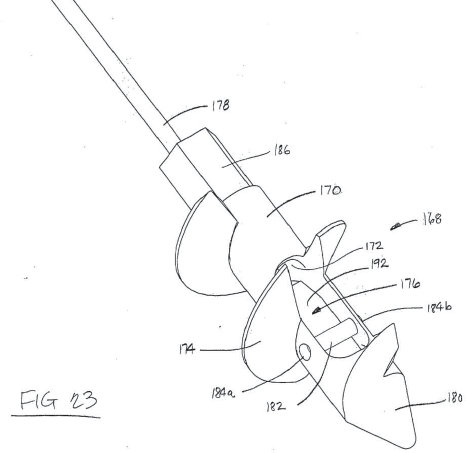

Smith & Nephew (hereinafter “Smith”) initiated an inter partes review of claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541. Smith alleged that claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541 were invalid as obvious over Gordon (U.S. Patent Application Publication No. 2006/0271060) in view of West (U.S. Patent No. 7,322,978) and alleged that claim 11 was anticipated by Curtis (U.S. Patent No. 5,464,427) (The discussion regarding Curtis (U.S. Patent No. 5,464,427) is not herein included). Smith argued that Gordon disclosed all the features claimed except for the rigid support. Gordon disclosed “a bone anchor in which a suture loops about a pulley 182 positioned within the anchor body. Figure 23 illustrates the pully 182 held in place in holes 184a, b.” Id. at 5 and 6.

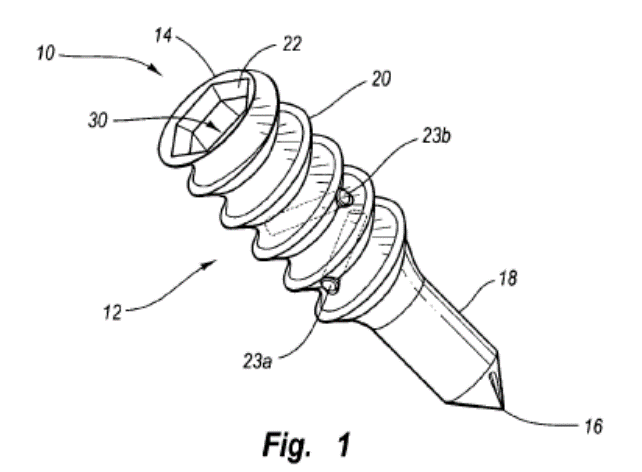

Figure 23 of Gordon

Smith acknowledged that the pulley of Gordon was not “integral with the anchor body to define a single-piece component”, a feature recited in claim 11 of Patent ‘541. Smith cited West to allege obviousness of this feature. West also disclosed a bone anchor wherein one or more pins are fixed within the bore of the anchor body. In West, “to manufacture the bone anchor, ‘anchor body 12 and posts 23 can be cast and formed in a die. Alternatively anchor body 12 can be cast or formed and post 23a and 23b inserted later.’” Id. at 7.

Figure 1 of West

Smith argued that it would have been obvious to a skilled artisan to form the bone anchor of Gordon by the casting process of West to thereby create a rigid support integral with the anchor body to define a single piece component, as recited in claim 11 of Patent ‘541. Smith’s expert testified that the casting process of West would “minimize the materials used in the anchor, thus facilitating regulatory approval, and would reduce the likelihood of the pulley separating from the anchor body.” Id. at 7. Smith asserted that the casting process of West was well-known in the art and that such a manufacturing process “would have been a simple design choice.” Id. at 7. Arthrex argued that a skilled artisan would not have been motivated to modify Gordon in view of West. The Board agreed with Smith that the claims were unpatentable. Arthrex filed an appeal.

Arthrex appealed the Board’s decision that Smith proved unpatentability of claims 10 and 11 in view of Gordon and West, on both a procedurally and a substantively basis, and the constitutionality of the IPR proceeding. The CAFC found that Arthrex’s procedural rights were not violated; that the Decision by the Board was supported by substantial evidence and the application of IPR to Patent ‘541 was constitutional.

IPR proceedings are formal administrative adjudications subject to the procedural requirements of the APA. See, e.g., Dell Inc. v. Acceleron, LLC, 818 F.3d 1293, 1298 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Belden, 805 F.3d at 1080. One of these requirements is that “‘an agency may not change theories in midstream without giving respondents reasonable notice of the change’ and ‘the opportunity to present argument under the new theory.’” Belden, 805 F.3d at 1080 (quoting Rodale Press, Inc. v. FTC, 407 F.2d 1252, 1256–57 (D.C. Cir. 1968)); see also 5 U.S.C. § 554(b)(3). Nor may the Board craft new grounds of unpatentability not advanced by the petitioner. See In re NuVasive, Inc., 841 F.3d 966, 971–72 (Fed. Cir. 2016); In re Magnum Oil Tools Int’l, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

Id. at 9.

Arthrex argued that the Board’s decision relied on a new theory of motivation to combine. Arthrex argued that the new theory violated their procedural rights by depriving them an opportunity to respond to said new theory. Arthrex argued that the Board’s reasoning differed from the Smith Petition by describing the casting method of West as “preferred.” The CAFC held that while the language used by the Board did differ from the Petition, said deviation did not introduce a new issue or theory as to the reason for combining Gordon and West. West disclosed “an ‘anchor body 12 and posts 23 can be cast and formed in a die. Alternatively anchor body 12 can be cast or formed and posts 23a and 23b inserted later’.” Id. at 10. The Smith Petition asserted that “a person of ordinary skill would have had ‘several reasons’ to combine West and Gordon, including that the casting process disclosed by West was a ‘well-known technique [whose use] would have been a simple design choice’.” (emphasis added) Id. at 10. In the written decision by the Board, the Board characterized West as disclosing two manufacturing methods, wherein the casting method was the “primary” and “preferred” method, and thus, a skilled artisan would have “applied West’s casting method to Gordon because choosing the ‘preferred option’ presented by West ‘would have been an obvious choice of the designer’.” Id. at 11. The CAFC noted that while the Board’s language of “preferred” differed from the language of the Petition, i.e. “well-known”, “accepted” and “simple”, the Board nonetheless relied upon the same disclosure of West as the Petition, the same proposed combination of the references and ruled on the same theory of obviousness, as presented in the Petition. “[t]he mere fact that the Board did not use the exact language of the petition in the final written decision does not mean it changed theories in a manner inconsistent with the APA and our case law…. the Board had cited the same disclosure as the petition and the parties had disputed the meaning of that disclosure throughout the trial. Id. As a result, the petition provided the patent owner with notice and an opportunity to address the portions of the reference relied on by the Board, and we found no APA violation.” Id. at 11.

Next, Arthrex argued that even if the Board’s decision was procedurally proper, an error was made by finding Smith had established a motivation to combine the cited art by a preponderance of the evidence. The CAFC held that there was sufficient substantial evidence to support the Board’s finding that a skilled artisan would be motivated to use the casting method of West to form the anchor of Gordon. First, the Board noted West’s disclosure of two methods of making a rigid support. Second, the wording by West suggested that casting was the preferred method. Third, Smith’s experts testified that the casting method would likely produce a stronger anchor, which in turn would be more likely to be granted regulatory approval. Also, casting would decrease manufacturing cost, produce an anchor that is less likely to interfere with x-rays and would reduce stress concentrations on the anchor. The CAFC agreed with Arthrex that there was some evidence that contradicts the Board’s decision, such as Arthrex’s expert’s testimony. However, “the presence of evidence supporting the opposite outcome does not preclude substantial evidence from supporting the Board’s fact finding. See, e.g., Falkner v. Inglis, 448 F.3d 1357, 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2006)”. Id. at 14. The CAFC refused to “reweight the evidence.” Id. at 14.

Lastly, the CAFC addressed Arthrex’s argument that an IPR is unconstitutional when applied retroactively to a pre-AIA patent. Since this argument was first presented on appeal, the CAFC could have chosen not to address it. However, exercising its discretion, the CAFC held that an IPR proceeding against Patent ‘541 was constitutional. Patent ‘541 was filed prior to the passage of the AIA, but was issued almost three years after the passage of the AIA and almost two years after the first IPR proceedings, on September 2, 2014. “As the Supreme Court has explained, ‘the legal regime governing a particular patent ‘depend[s] on the law as it stood at the emanation of the patent, together with such changes as have since been made.’” Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186, 203 (2003) (quoting McClurg v. Kingsland, 42 U.S. 202, 206 (1843)). Accordingly, application of IPR to Arthrex’s patent cannot be characterized as retroactive.” Id. at 18. The CAFC further explained that even if Patent ‘541 issued prior to the AIA, an IPR would have been constitutional. “[t]he difference between IPRs and the district court and Patent Office proceedings that existed prior to the AIA are not so significant as to ‘create a constitutional issue’ when IPR is applied to pre-AIA patents.” Id. at 18.

Takeaway

- Slight changes in language does not create a new theory of motivation to combine.

- However, a new theory of motivation to combine

may exist when:

- the Board

creates a new theory of obviousness by mixing arguments from two different

grounds of obviousness presented in a Petition.

- In re Magnum Oil Tools Int’l, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364, 1372–73, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- the claim construction by the Board varies

significantly from the uncontested construction announced in an institution

decision.

- SAS Institute v. ComplementSoft, LLC, 825 F.3d 1341, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- the Board

relies upon a portion of the prior art, as an essential part of its obviousness

finding, that is different from the portions of the prior art cited in the

Petition.

- In re NuVasive, Inc., 841 F.3d 966, 971 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- the Board

creates a new theory of obviousness by mixing arguments from two different

grounds of obviousness presented in a Petition.

When Motion to amend is filed in IPR, Opponent can cite additional references.

| July 18, 2017

Shinn Fu vs. Tire Hanger (Fed. Cir. 2017)

July 3, 2017

Before Prost, Reyna and Taranto. Opinion by Prost

Summary:

This is an appeal from an inter partes review (IPR) of USP 6,681,897 (“’897 patent”). The patentee filed a motion to amend. Petitioner opposed to the motion and presented arguments of unpatentability adding new references. The Board ignored Petitioner’s argument and granted the patent owner’s motion to amend and held the substitute claims patentable.

CAFC vacated and remanded holding that the Board did not properly consider the petitioner’s arguments in opposition to the Patentee’s motion to amend.

この事件は、米国特許6,681,897の当事者系レビュー(IPR)の決定の不服申立に関する。特許権者はIPRでクレームを補正する申立をした。請求人は先行技術引例を追加して補正クレームは特許性がないと主張した。審判部は、補正に対する請求人の主張を無視し、補正クレームは特許性ありとして補正を認めた。

CAFCは、審判部が、補正の申立に反対する主張を考慮しなかったのは不当であるとして、審決を取消し、補正に反対する主張の審理のため差戻した。

Statements made in IPR proceeding can be relied on to support a finding of prosecution disclaimer during claim construction

| July 5, 2017

Aylus Networks, Inc., v. Apple Inc.

May 11, 2017

Before Moore, Linn, and Stoll. Opinion by Stoll.

Summary

Patent owner Aylus Networks, Inc. sued Apple Inc. in district court for infringement of the U.S. Patent No. RE 44,412 (“the ‘412 patent”). Apple filed two separate IPRs challenging validity of all the claims. PTAB denied to institute claim 2 based on Aylus’s explanation of a limitation to claim 2. During claim construction in district court, this same explanation is relied on to support a finding of prosecution disclaimer. CAFC affirmed the district court’s finding of prosecution history disclaimer. CAFC also stated that prosecution disclaimer applies whether a statement is made before or after instituting an IPR.

Next Page »