CAFC upheld ITC’s ruling under the ‘Infrequently Applied’ Anderson two-step test regarding the enablement of open-ended ranges

| June 8, 2023

FS.com Inc. v. ITC and Corning Optical Corp.

Decided: April 20, 2023

Before Moore, Prost and Hughes. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

Corning filed a complaint with the ITC alleging FS was violating §337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (19 U.S.C. 1337), (a.k.a ‘unfair import’) by importing high-density fiber optic equipment that infringed several of their patents – U.S. Patent Nos. 9,020,320; 10,444,456; 10,120,153; and 8,712,206. The patents relate to fiber optic technology commonly used in data centers.

The Commission ultimately determined that FS’ importation of the high-density fiber optic equipment violated §337 and issued a general exclusion order prohibiting the importation of infringing high-density fiber optic equipment and components thereof and a cease-and-desist order directed to FS.

Subsequently, FS appealed the Commission’s determination that the claims of the ’320 and ’456 patents are enabled and its claim construction of “a front opening” in the ’206 patent.

ISSUE 1: ENABLEMENT

FS challenges the Commission’s determination that claims 1 and 3 of the ’320 patent and claims 11, 12, 15, 16, and 21 of the ’456 patent are enabled. These claims recite, in part, “a fiber optic connection density of at least ninety-eight (98) fiber optic connections per U space” or “a fiber optic connection of at least one hundred forty-four (144) fiber optic connections per U space.” FS argued these open-ended density ranges are not enabled because the specification only enables up to 144 fiber optic connections per U space.

A patent’s specification must describe the invention and “the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains . . . to make and use the same.” 35 U.S.C. § 112(a). To enable, “the specification of a patent must teach those skilled in the art how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without undue experimentation.”

In determining enablement, the Commission applied the two-part standard set forth in Anderson Corp. v. Fiber Composites, LLC, 474 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2007):

[O]pen-ended claims are not inherently improper; as for all claims their appropriateness depends on the particular facts of the invention, the disclosure, and the prior art. They may be supported if there is an inherent, albeit not precisely known, upper limit and the specification enables one of skill in the art to approach that limit.

Although the CAFC acknowledged that the Anderson test is infrequently applied, both FS and Corning agreed that the test governed their legal dispute. In applying this standard, the Commission determined the challenged claims were enabled because skilled artisans would understand the claims to have an inherent upper limit and that the specification enables skilled artisans to approach that limit.

The CAFC agreed, understanding the Commission’s opinion as determining there is an inherent upper limit of about 144 connections per U space. See Appellant’s Opening Br. at 51 (“The only potential finding by the Commission of an inherent upper limit to the open-ended claims is approximately 144 connections per 1U space.”). Specifically, that determination was based on the Commission’s finding that skilled artisans would have understood, as of the ’320 and ’456 patent’s shared priority date (August 2008), that densities substantially above 144 connections per U space were technologically infeasible. This was supported by expert testimony.

ISSUE 2: CLAIM CONSTRUCTION

The Commission construed “a front opening” in claim 14 of the ’206 patent as encompassing one or more openings. FS argued the proper construction of “a front opening” is limited to a single front opening and therefore its modules, which contain multiple openings separated by material or dividers, do not infringe claims 22 and 23. The CAFC disagreed.

The CAFC held that, generally, the terms “a” or “an” in a patent claim mean “one or more,” unless the patentee evinces a clear intent to limit “a” or “an” to “one.” 01 Communique Lab’y, Inc. v. LogMeIn, Inc., 687 F.3d 1292, 1297 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The CAFC concluded here that the claim language and written description did not demonstrate a clear intent to depart from this general rule.

Comments:

- Open-end ranges are not automatically improper. If such a range is required/desired during prosecution, apply the two-part standard set forth in Anderson: (1) is there inherent, albeit not precisely known, support for an upper limit and (2) does the specification enables one of skill in the art to approach that limit.

- The terms “a” or “an” in a patent claim remain to mean “one or more,” unless the patentee evinces a clear intent to limit “a” or “an” to “one.”

Common Sense Still Applies In Claim Construction

| May 13, 2023

Alterwan, Inc. v Amazon.com Inc

Decided: March 13, 2023

Before Lourie, Dyk, Stoll (Opinion by Dyk)

Summary:

For a claim term “non-blocking bandwidth,” the district court accepted the applicant-as-his-own-lexicographer definition set forth in the specification to mean “a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient.” This meant that bandwidth must be available even when the Internet is down – which is impossible (and hence, the parties’ agreed-upon stipulation of non-infringement with this claim interpretation). Courts will not rewrite “unambiguous” claim language to cure such absurd positions or to sustain validity. But, when the claim language is “not unambiguous” concerning the disputed interpretation, common sense applies in claim construction, especially in view of the proper context for the source of the applicant-as-his-own-lexicographer definition.

Procedural History:

Alterwan sued Amazon for patent infringement. After a Markman hearing and motions for summary judgment by both parties, the district court changed the claim construction for “cooperating service provider” at a summary judgment hearing to be a “service provider that agrees to provide non-blocking bandwidth.” The district court construed “non-blocking bandwidth” to be “a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient” which meant that the bandwidth will be available even if the Internet is down. With this updated construction, the parties filed a stipulation and order of non-infringement of the patents-in-suit. Amazon argued, and the patentee agreed, that if the claim required bandwidth provision even when the Internet is down, Amazon could not possibly infringe. The district court entered the stipulated judgment of non-infringement and the parties appealed.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 is as follows:

An apparatus, comprising:

an interface to receive packets;

circuitry to identify those packets of the received packets corresponding to a set of one or more predetermined addresses, to identify a set of one or more transmission paths associated with the set of one or more predetermined addresses, and to select a specific transmission path from the set of one or more transmission paths; and

an interface to transmit the packets corresponding to the set of one or more predetermined addresses using the specific transmission path;

wherein

each transmission path of the set of one or more transmission paths is associated with a reserved, non-blocking bandwidth, and

the circuitry is to select the specific transmission path to be a transmission path from the [sic] set of one or more transmission paths that corresponds to a minimum link cost relative to each other transmission path in the set of one or more transmission paths.

The specification states “the quality of service problem that has plagued prior attempts is solved by providing non-blocking bandwidth (bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient)…” (USP 8,595,478, col. 4, line 66 to col. 5, line 2). Accordingly, “non-blocking bandwidth” was defined by the applicant, acting as his own lexicographer, to mean “a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient.”

Normally, “[c]ourts may not redraft claims, whether to make them operable or to sustain validity” (citing, Chef Am., Inc. v. Lamb-Weston, Inc., 358 F.3d 1371, 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2004)). In Chef America, the claim limitation “heating the resulting batter-coated dough to a temperature in the range of about 400°F to 850°F” would lead to an absurd result in that the dough would be burnt. Instead, the limitation would be made operable if it recited heating the dough “at” a temperature in the range of about 400°F to 850°F. However, since the limitation at issue was unambiguous, the court declined to rewrite the claim to replace the term “to” with “at.”

However, the court noted that, “[h]ere, the claim language itself does not unambiguously require bandwidth to be available even when the Internet is inoperable.” So, “Chef America does not require us to depart from common sense in claim construction.” Without “unambiguous” claim language requiring the disputed interpretation (“a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient”), the court proceeded to check the context for the support for the disputed interpretation. That “context” included specification discussion of wide area network technology that uses the internet as a backbone, and several “quality of service” problems that arise from the use of the internet as a backbone, including latency problems in the delays for critical transmission packets getting from a source to a destination over that internet backbone. The patent’s solution was to provide “preplanned high bandwidth, low hop-count routing paths” between sites that are geographically separated. These preplanned routing paths are a “key characteristic that all species within the genus of the invention will share.” It is after this discussion that the specification then concludes “[i]n other words, the quality of service problem that has plagued prior attempts is solved by providing non-blocking bandwidth (bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient) and predefining routes for the ’private tunnel’ paths between points on the internet…”

Providing bandwidth even with the Internet being down is an impossibility. The specification describes operability and transmission over the Internet as a backbone and is completely silent about provision of bandwidth when the Internet is unavailable. In context, the definitional sentence for “non-blocking bandwidth” is addressing the problem of latency (when the Internet is operational), rather than providing for bandwidth even when there is no Internet. The court’s decision does not opine on what the meaning of non-blocking bandwidth is, but holds that “it does not require bandwidth when the Internet is down.”

Takeaways:

The court will not redraft claim language during claim construction to maintain operability or sustain validity when the claim language is unambiguous. But, when the claim language is “not unambiguous,” common sense applies, especially when looking at any source of the disputed interpretation in context.

APPLE MAKES ROTTEN CONVINCING THAT THE PTAB CANNOT CONSTRUE CLAIMS PROPERLY

| April 7, 2022

Apple, Inc vs MPH Technologies, OY

Decided: March 9, 2022

MOORE, Chief Judge, PROST and TARANTO. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

Apple appealed losses on 3 IPRs attempting to convince the CAFC that the PTAB had misconstrued numerous dependent claims for a myriad of reasons. The CAFC sided with the Board on all counts, in general showing deference to the PTAB and its ability to properly interpret claims.

Background:

Apple appealed from 3 IPRs wherein the PTAB had held Apple failed to show claims 2, 4, 9, and 11 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,494; claims 7–9 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,502; and claims 3, 5, 10, and 12–16 of U.S. Patent No. 9,838,362 would have been obvious. Apple’s IPR petitions relied primarily on a combination of Request for Comments 3104 (RFC3104) and U.S. Patent No. 7,032,242 (Grabelsky).

The patents disclose a method for secure forwarding of a message from a first computer to a second computer via an intermediate computer in a telecommunication network in a manner that allowed for high speed with maintained security.

The claims of the ’494 and ’362 patents cover the intermediate computer. Claim 1 of the ’494 patent was used as the representative independent claim for the patents:

1. An intermediate computer for secure forwarding of messages in a telecommunication network, comprising:

an intermediate computer configured to connect to a telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to be assigned with a first network address in the telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address having an encrypted data payload of a message and a unique identity, the data payload encrypted with a cryptographic key derived from a key exchange protocol;

the intermediate computer configured to read the unique identity from the secure message sent to the first network address; and

the intermediate computer configured to access a translation table, to find a destination address from the translation table using the unique identity, and to securely forward the encrypted data payload to the destination address using a network address of the intermediate computer as a source address of a forwarded message containing the encrypted data payload wherein the intermediate computer does not have the cryptographic key to decrypt the encrypted data payload.

The ’502 patent claims the mobile computer that sends the secure message to the intermediate computer.

Decision:

The Court first looked at dependent claim 11 of the ’494 patent and dependent claim 12 of the ’362 patent requirement that “the source address of the forwarded message is the same as the first network address.”

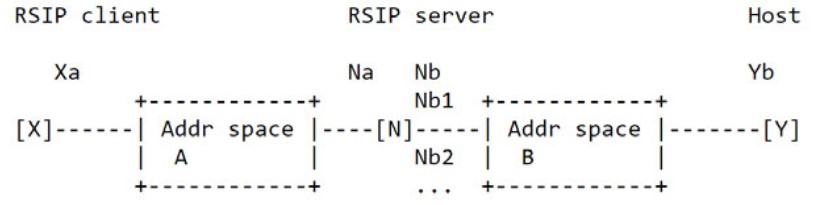

Apple had asserted RFC3104 disclosed this aspect of the claims. Specifically, RFC3104 discloses a model wherein an RSIP server examines a packet sent by Y destined for X. “X and Y belong to different address spaces A and B, respectively, and N is an [intermediate] RSIP server.” N has two addresses: Na on address space A and Nb on address space B, which are different. Apple asserted the message sent from Y to X is received by RSIP server N on the Nb interface and then must be sent to Na before being forwarded to X.

The model topography for RFC3104 is illustrated as:

In light thereof, Apple asserted that because the intermediate computer sends the message from Nb to Na before forwarding it to X, Na is both a first network address and the source address of the forwarded message. That the message was not sent directly to Na, Apple claimed, was of no import given the claim language. The Board had disagreed and found there was no record evidence that the mobile computer sent the message directly to Na.

In the appeal, Apple argued the Board misconstrued the claims to require that the mobile computer send the secure message directly to the intermediate computer. Rather, Apple asserted, the mobile computer need not send the message to the first network address so long as the message is sent there eventually. Specifically, Apple emphasized that the PTAB’s construction is inconsistent with the phrase “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” in claim 1 of the ’494 patent, upon which claim 11 depends.

The Court construed the plain meaning of “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” requires the mobile computer to send the message to the first network address. The phrase identifies the sender (i.e., the mobile computer) and the destination (i.e., the first network address). The CAFC maintained that the proximity of the concepts links them together, such that a natural reading of the phrase conveys the mobile computer sends the secure message to the first network address. Thus the CAC agreed with the PTAB that the plain language establishes direct sending.

The Court reenforced their holding by looking to the written description as confirming this plain meaning. Specifically, they noted it describes how the mobile computer forms the secure message with “the destination address . . . of the intermediate computer.” The mobile computer then sends the message to that address. There is no passthrough destination address in the intermediate computer that the secure message is sent to before the first destination address. Accordingly, like the claim language, the written description describes the secure message as sent from the mobile computer directly to the first destination address.

Second, the CAFC examined dependent claim 4 of the ’494 patent is similar to claim 5 of the ’362 patent. Claim 4 of the ‘494 recites:

…wherein the translation table includes two partitions, the first partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the secure message is sent to the first network address, the second partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the forwarded encrypted data payload is sent to the destination address. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board had interpreted “information fields” in this claim to require “two or more fields.” However, Apple’s obviousness argument relied on Figure 21 of Grabelsky, which disclosed a partition with only a single field. Therefore, the Board found Apple failed to show the combination taught this limitation. Moreover, the Board found Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the combination to use multiple fields.

On claim construction, Apple contended there is a presumption that a plural term covers one or more items. Apple maintained that patentees can overcome that presumption by using a word, like “plurality”, that clearly requires more than one item.

The Court found that Apple misstated the law. In accordance with common English usage, the Court presumes a plural term refers to two or more items. And found that this is simply an application of the general rule that claim terms are usually given their plain and ordinary meaning.

The Court also noted that there is nothing in the written description providing any significance to using a plurality of information fields in a partition. The CAFC therefore found that absent any contrary intrinsic evidence, the Board correctly held that fields referred to more than one field.

Third, the Court looked to Claim 2 of the ’494 patent and claim 3 of the ’362 patent. Claim 2 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is further configured to substitute the unique identity read from the secure message with another unique identity prior to forwarding the encrypted data payload. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board construed the word “substitute” to require “changing or modifying, not merely adding to.” Because it determined that RFC3104 merely involved “adding to” the unique identity, the Board found Apple had failed to show RFC3104 taught this limitation. The Board expressly addressed Apple’s argument from the hearing that “adding the header is the same as replacing the header because at the end of the day you have a different header than what you had before, a completely different header.” The Board disagreed with Apple and construed “substitute” to mean “changing, replacing, or modifying, not merely adding,” and observed that this construction disposed of Apple’s position.

The CAFC found no misconstruction by the PTAB with this interpretation. Moreover, the Court noted tat substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding that Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the prior art combination to include substitution. Apple relied solely on its expert’s contrary testimony, which the Court found the Board had properly disregarded as conclusory.

Fourth, the Court reviewed the PTAB’s interpretation of claim 9 of the ’494 patent, similar to claim 10 of the ’362 patent. Claim 9 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is configured to modify the translation table entry address fields in response to a signaling message sent from the mobile computer when the mobile computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the mobile computer is changed. (emphasis added in opinion).

Apple argued that establishing a secure authorization in RFC3104 includes creating a new table entry address field as required by the claim. The Board disagreed, reasoning that “modify[ing] the translation table entry address fields” requires having existing address fields when the mobile computer changes its address. Accordingly, it found Apple failed to how the combination taught this limitation. Apple argued before the CAFC that the “configured to modify the translation table entry address fields” limitation is purely functional and, thus, covers any embodiment that results in a table with different address fields, including new address fields. The CAFC disagreed, finding as the Board held, the plain meaning of “modify[ing] the translation table entry address fields” requires having existing address fields in the translation table to modify.

Specifically, the Court reasoned that the surrounding language showing the modification occurs “when the mobile computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the mobile computer is changed” further supports the existence of an address field prior to modification. Thus, the CAFC found that the limitation does not merely claim a result; it recites an operation of the intermediate computer that requires an existing address field.

Fifth and final, the Court reviewed claim 7 of the ’502 patent which recites:

…wherein the computer is configured to send a signaling message to the intermediate computer when the computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the computer is changed.

The Court noted that the RFC3104 disclosed an ASSIGN_REQUEST_RSIPSEC message that requests an IP address assignment. Apple argued that, when a computer moves to a new address, the computer uses this message as part of establishing a secure connection and, in the process, the intermediate computer knows the address has been changed. The Board had found that the message was not used to signal address changes. Accordingly, the Board determined that Apple had failed to show that the intermediate computer knows that the address is changed, as required by the claim language. Apple reprises its arguments, which the Board had rejected.

The CAFC noted that claims 7–9 of the ’502 patent require a computer to send a message to the intermediate computer “such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the computer is changed.” The Court affirmed the Board’s contrary finding was supported by substantial evidence, including MPH’s expert testimony and RFC3104 itself. MPH’s expert testified that a skilled artisan would not have understood the relevant disclosure in RFC3104 to teach any signal address changes. Agreeing with the PTAB, the Court found that the relevant disclosure in RFC3104 relates to establishing an RSIP-IPSec session, not to signal address changes. Hence, they saw no reason why the Board was required to equate communicating a new address and signaling an address change. They therefore concluded that substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding.

In the end, the CAFC affirmed all of the Board’s final written decisions holding that claims 2, 4, 9, and 11 of the ’494 patent; claims 7–9 of the ’502 patent; and claims 3, 5, 10, and 12–16 of the ’362 patent would not have been obvious.

Take away:

Although the CAFC reviews claim construction and the Board’s legal conclusions of obviousness de novo, they are inclined toward giving deference to the PTAB. Caution should be taken in attempting to convince the CAFC that the Board has misconstrued claims unless there is a clear showing that the Board did not follow the Phillips standard (Claim terms are given their plain and ordinary meaning, which is the meaning one of ordinary skill in the art would ascribe to a term when read in the context of the claim, specification, and prosecution history).

What Does It Mean To Be Human?

| November 26, 2020

Immunex Corp v. Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC

Prost, Reyna and Taranto.Opinion by Prost

October 13, 2020

Summary

This is a consolidated appeal from two Patent and Trademark Appeal Board (“Board”) decisions in Inter partes reviews (IPR) of US Patent No. 8,679,487 (‘487 patent) owned by Immunex. In the first IPR the Board invalidated all challenged claims. Immunex appealed the construction of the claim term “human antibodies.” In the other IPR, involving a subset of the same claims, the Board did not invalidate the patent for reason of inventorship. Sanofi appealed the Boards inventorship determination.

Briefly, the CAFC agreed with the Board’s claim construction and affirmed the invalidity decision. Since this left no claims valid, the CAFC dismissed Sanofi’s inventorship appeal.

The ’487 patent is directed to antibodies that bind to human interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptor. This appeal concerned what “human antibody” means in this patent. That is, in the context of this patent, must a human antibody be entirely human, or does it include partially human, for example humanized?

Amid infringement litigation, Sanofi filed three IPR’s against the ‘487 patent, two if which were instituted. In one final decision the Board concluded that the claims were unpatentable as obvious over two references, Hart and Schering-Plough. Hart describes a murine antibody that meet all the limitations of claim 1 except that it is fully murine, so not human at all. The Schering-Plough reference teaches humanizing murine antibodies.

In response, Immunex insisted that the Board had erred in construction of “human antibody” to include humanized antibodies.

After Appellate briefing was complete, Immunex filed with the PTO a terminal disclaimer of its patent. The PTO accepted it, and the patent expired May 26, 2020, just over two months prior to oral arguments. Immunex then filed a citation apprising the CAFC of (but not explaining the reason for) its terminal disclaimer and asking the court to change the applicable construction standard.

Specifically, in all newly filed IPRs, the Board now applies the Phillips district-court claim construction standard. However, when Sanofi filed its IPR, the Board applied this standard to expired patents only. To unexpired patents, it applied the Broadest Reasonable Interpretation (BRI) standard.

Immunex urged the CAFC to apply Phillips citing Wasica Finance GmbH v., Continental Automotive Systems, Inc., 853 F.3d 1272, 1279 (Fed. Cir. 2017) and In re CSB-System International 832 F. 3d 1335, as support. However, unlike here, the patents at issues in these cases had expired before the Board’s decision. The CAFC noted that it had applied the Phillips standard when a patent expired on appeal. Nonetheless, the CAFC clarified that in these cases the patent terms had expired as expected and not cut short by a litigant’s terminal disclaimer.

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed it will review the Board’s claim construction under the BRI standard.

Initially, the CAFC turned to the intrinsic record, specifically, the claims, the specification, and the prosecution history.

The CAFC noted that the claims themselves were not helpful as the dependent claims provided no further guidance.

Next, the CAFC noted that while the specification gave no actually definition, the usage of “human” throughout the specification confirmed its breadth. Specifically, the specification contrasts “partially human’ with “fully human.” For instance, the specification states that “an antibody…include, but are not limited to, partially human…. fully human.” Thus, the specification makes it clear that “human antibody” is a broad category encompassing both “fully” and “partially.”

Immunex insisted that the Board undervalued the prosecution history. While the CAFC agreed, it concluded the prosecution history supported the Board’ construction.

First, they noted that Immunex had used the term “fully human” and “human” in the same claim of another of its patents in the same family. Next, claim 1 as originally presented merely stated “an isolated antibody” and “human” were added during prosecution.

As a result, a dependent claim which recited ‘a human, partially human, humanized or chimeric antibody’ was cancelled. Immunex suggested that the amendment “surrendered” the partially human embodiment. The CAFC disagreed.

The Board noted that “human” was not added to overcome an anticipating reference that disclosed ‘nonhuman.’ The CAFC also noted that the claim language does not require the exclusion of partially human embodiments. Thus, the CAFC held that nothing indicates that “human” was added to limit the scope to fully human.

The CAFC noted that in a post-amendment office action, the Examiner expressly wrote that the amended “human” antibodies encompassed “humanized” antibodies and that Immunex had made no effort to correct this understanding.

Next, the CAFC addressed the role of extrinsic evidence. Immunex argued that the Board had failed to establish how a person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood the term. Immunex had provided expert testimony to argue that “human antibody” would have been limited to “fully human.”

The CAFC held that while it is true that they seek the meaning of a claim term from the perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art, the key is how that person would have understood the term in view of the specification. That, while extrinsic evidence may illuminate a well-understood technical meaning, that does not mean that litigants can introduce ambiguity in a way that disregards usage in the patent itself.

Here, the extrinsic evidence provided conflicts the intrinsic evidence. Priority is given to the intrinsic evidence.

Lastly, the CAFC discussed the Boards’ departure from an earlier court’s claim construction. That is, in the litigation that prompted this IPR, a district court construed “human” to mean “fully human” only, under the narrower Phillips-based construction. However, the CAFC reiterated that the Board “is not generally bound by a previous judicial construction of a claim term.”

Thus, to conclude, the CAFC affirmed the Board’s claim construction under the BRI standard, and thus its invalidity judgment based thereon.

Take-away

- Claim drafting – words matter

- The importance of dependent claims

- Be mindful of amendments made during prosecution that are not done for the purpose of overcoming prior art.

- In claim construction, intrinsic evidence has priority over extrinsic evidence when they conflict.

- Be mindful of comments made by the Examiner during prosecution in an action (office action, notice of allowance, etc.,) regarding interpretation of the claims.

The limitations of a “wherein” clause

| October 15, 2019

Allergan Sales, LLC v. Sandoz, Inc., No. 2018-2207

August 29, 2019

Prost, Newman and Wallach. Opinion by Wallach

Summary

Appellees (Allergan hereon in) sued Appellants (Sandoz hereon in) asserting that their Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) for a generic version of Allergan’s ophthalmic drug (Combigan®) infringed on their U.S. Patent Nos. 9,770,453: 9,907,801: 9,907,802. The District Court found limiting a number of “wherein” clauses in the Patents’ and granted Allergan’s motion for Preliminary Injection. Sandoz appealed. CAFC affirmed.

As an exemplary claim, independent claim 1 of the ‘453 patent is as follows:

A method of treating a patient with glaucoma or ocular hypertension comprising topically administering twice daily to an affected eye a single composition comprising 0.2% w/v brimonidine tartrate and 0.68% w/v timolol maleate,

wherein the method is as effective as the administration of 0.2% w/v brimonidine tartrate monotherapy three times per day and

wherein the method reduces the incidence of one o[r] more adverse events selected from the group consisting of conjunctival hyperemia, oral dryness, eye pruritus, allergic conjunctivitis, foreign body sensation, conjunctival folliculosis, and somnolence when compared to the administration of 0.2% w/v brimonidine tartrate monotherapy three times daily.

The specifications contained a clinical study, referred to as Example II, and it is the results thereof that are reflected in “the disputed “wherein” clauses (i.e., the efficacy and safety of the claimed combination).

Allergan argued that the “wherein” clauses were limiting, whereas Sandoz argued that the “wherein” clauses were not. Specifically, Sandoz argued that the “wherein” clauses “merely state the intended results” and so are not “material to patentability.” Sandoz argued that the only positive limitation in the claim[s] is the administering step. Sandoz relied upon previous cases to argue that “…whereby [or wherein] clause in a method claim is not given weight when it simply expresses the intended result of a process step positively recited.”); Bristol–Myers Squibb Co. v. Ben Venue Labs., Inc., 246 F.3d 1368, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2001).

The District Court and CAFC disagreed. The courts looked to the specification, and to the prosecution history wherein the Applicant had relied upon the results of administering the combination drug to assert patentability over the prior art. It was also noted that the Examiner had explicitly relied upon the “wherein” clauses in his explanation as to why the claims were novel and non-obvious over the prior art in the Notice of Allowance.

The courts differentiated this case from the previous case argued by Sandoz in that, “In Bristol–Myers we expressly noted that the disputed claim terms “w[ere] voluntarily made after the examiner had already indicated . . . the claims were allowable” and such “unsolicited assertions of patentability made during prosecution do not create a material claim limitation.”

Accordingly, “the District Court “f[ound] that the ‘wherein’ clauses are limiting because they are material to patentability and express the inventive aspect of the claimed invention” and the CAFC affirmed.

Take-away

“The specification is always highly relevant to the claim construction analysis and is, in fact, the single best guide to the meaning of a disputed term.” Prosecution history and the Examiner’s express rational for allowance are also highly relevant.

Ambiguity in specific definition of claim terms

| October 25, 2017

ORGANIK KIMYA AS, v. ROHM AND HAAS COMPANY

October 11, 2017

Before Prost, Newman, and Taranto. Opinion by Newman.

Summary:

In the inter partes review (“IPR”) proceedings, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) made claim interpretation about claimed “swelling agent” by relying on patentee’s specific definition provided in the specification and decided that the alleged prior arts fail to disclose such “swelling agent.” Appellant, Organik Kimya AS argues that the specific definition includes ambiguity due to open-ended definition and the claims cannot be reasonably interpreted to exclude those prior arts. The court affirmed the decision of PTAB. The specification contained many definitions of technical terms. Careful wording would be more desired in drafting functional definition for claim terms, which provides specific meaning different from ordinary and customary one.

A Distinction Without A Difference

| March 21, 2016

Ulf Bamberg, Peter Kummer, Ilona Stiburek v. Jodi A. Dalvey, Nabil F. Nasser

March 9, 2016

Before Moore, Hughes and Stoll. Opinion by Hughes.

Summary:

The CAFC upheld the Board’s decision that the Bamberg claims were correctly interpreted in light of the Dalvey patents from which they were copied, and functional limitations were not improperly imported.

The CAFC upheld that, in light of the claim interpretation, the Bamberg specification failed to provide adequate written description.

The CAFC found that the Board did not err in denying Bamberg’s motion to amend the claim set due to a lack of claim chart.

Claim term “at least one component of [a unit]” excludes the entire unit – expert testimony cannot override intrinsic evidence

| April 17, 2015

Enzo Biochem Inc. v. Applera Corp. (Precedential)

March 16, 2015

Before: Prost, Newman and Linn. Opinion by Prost, Dissent by Newman.

Summary

In this case, grammatical construction and invention “purpose” beat expert testimony and claim differentiation, leading to reversal of the District Court’s claim interpretation.

One might have thought that the Federal Circuit would make a point of carefully applying the different standards of review when a District Court’s claim construction relied in part on extrinsic evidence (“clear error” for findings based on extrinsic evidence, instead of “de novo” review for intrinsic evidence, see Teva Pharm. USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc. (Jan. 20, 2015)).

This decision suggests a different trend, toward minimizing the importance of extrinsic evidence in claim interpretation, which allows the Federal Circuit to maintain its customary high level of scrutiny.

Entirely reasonable? “Black box” claim interpretation by split Federal Circuit panel leaves us in the dark

| February 13, 2013

Harris Corp. v. Fed Ex Corp. (non-precedential)

January 17, 2013

Panel: Lourie, Clevenger, and Wallach. Opinion by Clevenger. Dissent by Wallach

Summary:

Over a dissent, the Federal Circuit panel makes a strict interpretation of “antecedent basis,” which results in a reversal of the District Court’s claim interpretation, and a remand to re-evaluate the infringement issue.

Harris’s patents cover methods and systems for using spread spectrum radio signals to send flight data from a plane’s “black box” to an airport receiver at the end of the flight. The invention includes steps of generating, accumulating and storing flight data in the plane during the flight, followed by a step of “transmitting the accumulated, stored generated aircraft data” once at the airport.

At the District Court, a jury found that Fed Ex willfully infringed Harris’s patents by using a “design-around” system that transmits all flight data except an optional 5-minute segment.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit panel majority holds that Harris patent claims are limited to the transmission of “all data generated during the flight,” not just any data subset representative of the flight. The panel’s view is that the narrower interpretation is “entirely reasonable” since the transmitting step refers to the generating step.

In contrast, the dissent sees the claim language as open, so that it would be “counterintuitive” to require that all the generated data must be transmitted.

Tags: antecedent basis > claim construction > claim interpretation