What’s the Problem? CAFC reverses PTAB for identifying the problem to be solved in finding combined references analogous when the burden was properly on the Petitioner

| May 11, 2023

Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GMBH v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Decided: May 9, 2023

Before Reyna, Mayer and Cunningham. Opinion by Cunningham.

Summary:

The Court reverses a PTAB final written decision finding all challenged claims of Safoni’s patent unpatentable as obvious over prior art. The Court held that Mylan improperly argued a first prior art reference is analogous to another prior art reference and not the challenged patent. Therefore Mylan failed to meet its burden to establish obviousness premised on the first reference since the Board’s factual finding that the first reference is analogous to the patent-in-suit is unsupported by substantial evidence.

Background:

Mylan filed an IPR against Sanofi’s RE47,614 (“the ‘614 patent”) alleging its unpatentability in light of a combination of three prior art references: (1) U.S. Patent Application No. 2007/0021718 (“Burren”); (2) U.S. Patent No. 2,882,901 (“Venezia”); and (3) U.S. Patent No. 4,144,957 (“de Gennes”). Claim 1 of the ‘614 patent is directed to a drug delivery device with a spring washer arranged within a housing so as to exert a force on a drug carrying cartridge and to secure the cartridge against movement with respect to a cartridge retaining member, the spring washer has at least two fixing elements configured to axially and rotationally fix the spring washer relative to the housing.

Mylan asserted that Burren with Venezia taught the use of spring washers within drug-delivery devices and relied on de Gennes to add “snap-fit engagement grips” to secure the spring washer. Burren and Venezia were both within the field of a drug delivery system. However, de Gennes was non-analogous art being directed to a clutch bearing in the automotive field. Sanofi argued that the combination was improper because de Gennes was non-analogous art. Mylan responded that de Gennes was analogous in that it was relevant to the pertinent problem in the drug delivery art and cited to Burren as providing a problem which a skilled artisan may look to extraneous art to solve.

The PTAB found that Burren in combination with Venezia and de Gennes does render the challenged claims unpatentable relying on the “snap-fit connection” of de Gennes as equivalent to the “fixing elements” of the ’614 patent. Sanofi appealed.

Discussion:

In its appeal, Sanofi argued that the PTAB “altered and extended Mylan’s deficient showing” by analyzing whether de Gennes constitutes analogous art to the ’614 patent when Mylan, the petitioner, only presented its arguments with respect to Burren (i.e. other prior art). Mylan countered that the Board had found de Gennes as analogous art because there was “no functional difference between the problem of Burren and the problem of the ‘614 patent.”

In its review of the law governing whether prior art is analogous, the CAFC noted that “we have consistently held that a patent challenger must compare the reference to the challenged patent” and, citing precedent, noted that the proper test is whether prior art is “reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved.” The CAFC expanded thereon stating:

Mylan’s arguments would allow a challenger to focus on the problems of alleged prior art references while ignoring the problems of the challenged patent. Even if a reference is analogous to one problem considered in another reference, it does not necessarily follow that the reference would be analogous to the problems of the challenged patent…[broad construction of analogous art]… does not allow a fact finder to focus on the problems contained in other prior art references to the exclusion of the problem of the challenged patent.

The Court re-emphasized that the petitioner has the burden of proving unpatentability and that they have reversed the Board’s patentability determination where a petitioner did not adequately present a motivation to combine.

Conclusion:

The CAFC concluded that the Board’s decision did not interpret Mylan’s obviousness argument as asserting de Gennes was analogous to the ’614 patent, but rather improperly relied on de Gennes being analogous to the primary reference, Burren. As such, Mylan did not meet its burden to establish obviousness premised on de Gennes; and therefore, the Board’s factual finding that de Gennes is analogous to the ’614 patent is unsupported by substantial evidence. The Court reversed the finding of obviousness.

Take away:

- Relying on non-analogous art to support an obviousness contention requires looking at the problems the inventor of the patent-in-issue would find pertinent not those set forth in other relied upon prior art. Arguments that a problem solved by non-analogous art should focus on the inventor of the patent-in-issue as recognizing the problem to be solved not generally problems recognized in the art.

- Petitioner’s in IPRs should be cautious relying on the PTAB formulating an argument outside of those clearly set forth in their filings. Extrapolation of Petitioner’s arguments by the PTAB can open the possibility of a reversal based on lack of substantial evidence.

Limitations of Result-Based Functional Language and Generic Computer Components in Patent Eligibility

| May 2, 2023

Hawk Technology Systems, Llc V. Castle Retail, LLC

Before REYNA, HUGHES, and CUNNINGHAM, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The district court granted Castle Retail’s motion, finding that the patent claims were directed towards the abstract idea of storing and displaying video without providing an inventive step to transform the abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention. The district court dismissed Hawk’s case, and Hawk appealed. The Federal Circuit upheld the district court’s decision, affirming that the patent claims were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Background

Hawk Technology Systems is the owner of a US Patent No. 10,499,091 ( the ’91 patent) entitled “High-Quality, Reduced Data Rate Streaming Video Product and Monitoring System.” The patent was filed in 2017 and granted in 2019, with priority claimed back to 2002. It describes a technique for displaying multiple stored video images on a remote viewing device in a video surveillance system, using a configuration that utilizes existing broadband infrastructure and a generic PC-based server to transmit signals from cameras as streaming sources at low data rates and variable frame rates. The patent claims that this approach reduces costs, minimizes memory storage requirements, and enhances bandwidth efficiency.

Hawk Technology Systems sued Castle Retail for patent infringement in Tennessee, alleging that Castle Retail’s use of security surveillance video operations in its grocery stores infringed on Hawk’s patent. Castle Retail moved to dismiss the case, arguing that the patent claims were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101, as they were directed towards ineligible subject matter.

The ‘091 patent contains six claims, but the appellant, Hawk Technology Systems, did not assert that there was any significant difference between the claims regarding eligibility. As a result, claim 1 was selected as representative, which recites:

1. A method of viewing, on a remote viewing device of a video surveillance system, multiple simultaneously displayed and stored video images, comprising the steps of:

receiving video images at a personal computer based system from a plurality of video sources, wherein each of the plurality of video sources comprises a camera of the video surveillance system;

digitizing any of the images not already in digital form using an analog-to-digital converter;

displaying one or more of the digitized images in separate windows on a personal computer based display device, using a first set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image in each window;

converting one or more of the video source images into a selected video format in a particular resolution, using a second set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image;

contemporaneously storing at least a subset of the converted images in a storage device in a network environment;

providing a communications link to allow an external viewing device to access the storage device;

receiving, from a remote viewing device remoted located remotely from the video surveillance system, a request to receive one or more specific streams of the video images;

transmitting, either directly from one or more of the plurality of video sources or from the storage device over the communication link to the remote viewing device, and in the selected video format in the particular resolution, the selected video format being a progressive video format which has a frame rate of less than substantially 24 frames per second using a third set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image, a version or versions of one or more of the video images to the remote viewing device, wherein the communication link traverses an external broadband connection between the remote computing device and the network environment; and

displaying only the one or more requested specific streams of the video images on the remote computing device.

In September 2021, the district court granted Castle Retail’s motion to dismiss the case. The court found that the claims in Hawk’s ‘091 patent failed the two-part Alice test. The court determined that the ‘091 patent is directed to an abstract idea of a method for storing and displaying video, and that the claimed elements are generic computer elements without any technological improvement.

Hawk’s argument that the temporal and spatial parameters are the inventive concept was also rejected, as the claims and specification failed to explain what those parameters are or how they should be manipulated. The district court also found that the claimed “analog-to-digital converter” and “personal computer based system” were not technological improvements, but rather generic computer elements. Additionally, it determined that the “parameters and frame rate” defined in the claims and specification did not appear to be more than manipulating data in a way that has been found to be abstract.

The district court concluded that the claims can be implemented using off-the-shelf, conventional computer technology and entered judgment against Hawk. Hawk appealed the decision.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit applied Alice step one in this case to determine if the ’091 patent claims were directed to an abstract idea. They agreed with the district court’s conclusion that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “storing and displaying video.”

The Federal Circuit further clarified that the claims are directed to a method of receiving, displaying, converting, storing, and transmitting digital video “using result-based functional language.” Two-Way Media Ltd. v. Comcast Cable Commc’ns, LLC, 874 F.3d 1329, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The claims require various functional results of “receiving video images,” “digitizing any of the images not already in digital form,” “displaying one or more of the digitized images,” “converting one or more of the video source images into a selected video format,” “storing at least a subset of the converted images,” “providing a communications link,” “receiving . . . a request to receive one or more specific streams of the video images,” “transmitting . . . a version of one or more of the video images,” and “displaying only the one or more requested specific streams of the video images.”

Hawk argued that the ’091 patent claims were not directed to an abstract idea but to a specific technical problem and solution related to maintaining full-bandwidth resolution while providing professional quality editing and manipulation of digital video images. However, this argument failed because the Federal Circuit found that the claims themselves did not disclose how the alleged goal was achieved and that converting information from one format to another is an abstract idea. Furthermore, the claims did not recite a specific solution to make the alleged improvement concrete and, at most, recited abstract data manipulation. Therefore, the ’091 patent claims lacked sufficient recitation of how the purported invention improved the functionality of video surveillance systems and amounted to a mere implementation of an abstract idea.

At Alice step two, the claim elements were examined individually and as a combination to determine if they transformed the claim into a patent-eligible application of the abstract idea. The district court found that the claims did not show a technological improvement in video storage and display and that the limitations could be implemented using generic computer elements.

Hawk argued that the claims provided an inventive solution that achieved the benefit of transmitting the same digital image to different devices for different purposes while using the same bandwidth, citing specific tools, parameters, and frame rates. The Federal Circuit acknowledged that the claims mentioned “parameters.” However, the claims did not specify what these parameters were, and at most they pertained to abstract data manipulation such as image formatting and compression. Hawk did not contest that the claims involved conventional components to carry out the method. The Federal Circuit also noted that the ‘091 patent affirmed that the invention was meant to “utilize” existing broadband media and other conventional technologies. Thus, the Federal Circuit found that there is nothing inventive in the ordered combination of the claim limitations and noted that Hawk has not pointed to anything inventive.

The Federal Circuit determined that the claims in the ‘091 patent did not transform the abstract concept into something substantial and therefore did not pass the second step of the Alice test. As a result, the Federal Circuit concluded that the ‘091 patent is ineligible since its claims address an abstract idea that was not transformed into eligible subject matter.

Takeaway

- Reciting an abstract idea performed on a set of generic computer components does not contain an inventive concept.

- Claims that use result-based functional language in combination with generic computer components may not be sufficient to transform an abstract idea into patent-eligible subject matter.

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words in Establishing Public Use When Utility is Ornamental

| April 3, 2023

In re WinGen LLC

Decided: February 2, 2023

Before Lourie, Taranto, and Stoll (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

After reading this nonprecedential decision, one may wonder why it was not designated precedential, in view of quotes from the decision such as “what is necessary for an invalidating prior public use of a plant has not been considered by this court” and “This case therefore presents a unique question.” Nonetheless, a number of very interesting topics are raised regarding different ways to secure patent protection (a plant patent and/or a utility patent), and what may be considered an invalidating public use. This decision becomes more interesting when exploring the background of the patent in question which was not discussed in the decision, namely, why was a reissue pursued in the first place. Based on the author’s opinion, the reissue application may have become necessary due to a misunderstanding of the invention by both the Examiner and the prosecuting attorney.

Background

U.S. Patent No. 9,313,959 is directed to a Calibrachoa plant. Claim 1 is representative:

1. A Calibrachoa plant comprising at least one inflorescence with a radially symmetric pattern along the center of the fused petal margins, wherein said pattern extends from the center of the inflorescence and does not fade during the life of the inflorescence,

and wherein the Calibrachoa plant comprises a single half-dominant gene, as found in Calibrachoa variety ‘Cherry Star,’ representative seed having been deposited under ATCC Accession No. PTA-13363.

Reissue Application 15/229,819 was filed as a broadening reissue to delete “representative seed having been deposited under ATCC Accession No. PTA-13363”.[1] During prosecution of the reissue application, a final rejection was made that included rejections for lack of written description, nonstatutory double patenting, lack of enablement, and prior public use. On appeal to the Board, the Board reversed all the rejections except for the prior public use rejections. The Board found that a display of ‘Cherry Star’ had been accessible to the public at an event at The Home Depot. This event was hosted by Proven Winners North America LLC, a common shareholder with the original assignee of the ‘959 patent, Plant 21 LLC. Proven Winners is a brand management and marketing entity. Plant 21 entrusted Proven Winners with samples of ‘Cherry Star’ to show at a private event at The Home Depot. At the event, the attendees were not permitted to take cuttings, seeds, or tissue samples of the plant. However, the attendees were provided with a leaflet to bring home that included a photograph and brief description of the plant. In addition, the visitors were under no obligations of confidentiality. The visitors were not provided with any gene or breeding information regarding ‘Cherry Star’. The handout is shown below:

The Board’s decision also commented that it was undisputed that a complete invention comprising all the claimed characteristics[2] was on display at The Home Depot event.

WinGen appealed to the CAFC, arguing that the Board erred in finding prior public use when all the claimed features were not made available to the public. In particular, the attendees would not have been aware of or able to readily ascertain that ‘Cherry Star’ resulted from a “single half dominant gene”, and thus the display was not an invalidating prior public use.

Discussion

Under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b), an applicant may not receive a patent for an invention that was in public use “more than one year prior to the date of application in the United States.” To determine an invalidating public use, the court considers whether the purported use (1) was accessible to the public or (2) was commercially exploited. Here, the CAFC commented that there was only one prior case involving prior public use of a plant (Delano Farms v. Cal. Table Grape Comm’n, 778 F.3d 1243 (Fed. Cir. 2015). That case involved the unauthorized growing of the claimed grapes in locations visible from public roads. Although the grapes were viewable to the public, they were not labeled in any way and there was no evidence that anyone recognized the grapes as the claimed varietal.

The CAFC distinguished this prior case from what occurred at The Home Depot event. At the event, ‘Cherry Star’ was indisputably identified. Although the handout itself was not a public use, the leaflet confirms that the physical plant on display was in fact ‘Cherry Star’.

The CAFC further commented that the use of ‘Cherry Star’ is purely ornamental, in contrast to the grapes in Delano Farms.

The CAFC noted that this case presents a unique question with respect to a purpose of ornament than other decisions regarding alleged public uses. For example, in Motionless Keyboard Co. v. Microsoft Corp., 486 F.3d 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2007), there was no evidence showing the invention was used for its intended purpose (visual display of a keyboard did not constitute public use because it was not connected to a computer or other device).

Although this all makes sense, whatever happened to WinGen’s argument regarding the claimed genetics (“comprises a single half-dominant gene”)? The CAFC dismissed this argument as WinGen “did not meaningfully present such an argument to the Board. We agree with the Director that such an argument was forfeited.” Had such an argument been made, it is likely there would have been a different outcome.

Background Notes

I was curious why the reissue became necessary. I looked at the prosecution history of the original patent and noted several interesting things that occurred during prosecution. Prior to the first action, there were several third-party prior art submissions. This is indicative that there were competitors concerned about a utility patent issuing. One submission included a photograph of ‘Cherry Star’. This photograph was initially entered by the USPTO, but then later expunged after the patent applicant filed a petition. A subsequent third-party submission included another photograph from a publication describing ‘Cherry Star’ which was entered into the record.

The Examiner’s first office action included numerous rejections. An interview was conducted prior to filing a response which seemed productive in that the Examiner suggested amendment to include the semi-dominant gene as found in the deposited variety ‘Cherry Star’. However, there was also an objection made by the Examiner regarding the use of “tissue” in the specification instead of “seed” in reference to the biological material which was deposited. The applicant proceeded with the Examiner’s suggested amendment, but this may have been the mistake that led to the need for a reissue application. The original specification described that the plant is produced from tissue having been deposited. The use of “tissue” seems to have meant the genetic material as opposed to seeds. As described in the specification:

Additionally, and as known in the art, Calibrachoa plants can be reproduced asexually by vegetative propagation or other clonal method known in the art. For example, and in no way limiting, a Calibrachoa plant having at least one inflorescence with a radially symmetric pattern along the center of the fused petal margins, can be reproduced by (a) obtaining a tissue cutting from said plant, (b) culturing said tissue cutting under conditions sufficient to produce a plantlet with roots and shoots; and (c) growing said plantlet to produce a plant,

In other words, the plants themselves are asexually reproduced. Growing plants from the seeds may not produce the claimed plant.

[1] Observed by the author from the image file wrapper of the reissue application.

[2] This admission or lack of dispute proves detrimental to the patentee.

A Claim term referring to an antecedent using “said” or “the” cannot be independent from the antecedent

| February 24, 2023

Infernal Technology, LLC v. Activision Blizzard Inc.

Decided: January 24, 2023

Moore, Chen, Stoll. Opinion by Chen.

Summary:

Infernal sued Activision for infringement of its patents to lighting and shadowing methods for use with computer graphics based on nineteen Activision video games. Based on the construction of the claim term “said observer data,” Activision filed a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement. The CAFC agreed with the District Court’s analysis of the noted claim term and affirmed the motion for summary judgment of non-infringement.

Details:

Infernal owns the related U.S. Patent Nos. 6,362,822 and 7,061,488 to “Lighting and Shadowing Methods and Arrangements for Use in Computer Graphic Simulations” providing methods of improving how light and shadow are displayed in computer graphics. Claim 1 of the ‘822 patent is provided:

1. A shadow rendering method for use in a computer system, the method comprising the steps of:

[1(a)] providing observer data of a simulated multi-dimensional scene;

[1(b)] providing lighting data associated with a plurality of simulated light sources arranged to illuminate said scene, said lighting data including light image data;

[1(c)] for each of said plurality of light sources, comparing at least a portion of said observer data with at least a portion of said lighting data to determine if a modeled point within said scene is illuminated by said light source and storing at least a portion of said light image data associated with said point and said light source in a light accumulation buffer; and then

[1(d)] combining at least a portion of said light accumulation buffer with said observer data; and

[1(e)] displaying resulting image data to a computer screen.

(Emphasis added).

The parties agreed to the construction of the term “observer data” as meaning “data representing at least the color of objects in a simulated multi-dimensional scene as viewed from an observer’s perspective.” The district court adopted this construction. Based on this construction and the plain and ordinary meaning of the limitation “said observer data” in step 1(d), Activision filed a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement, and the district court granted the summary judgment.

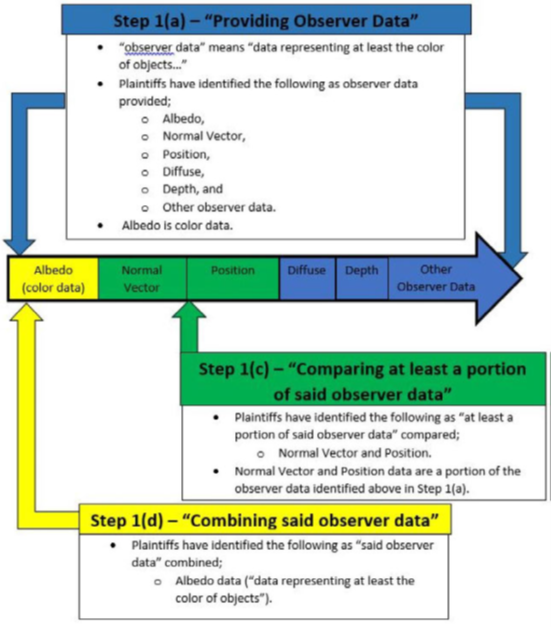

On appeal, Infernal argued that the district court misapplied its own construction of “observer data.” Infernal argued that “observer data” can refer to different data sets in steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d), each different data set independently satisfying the “observer data” construction. Step 1(a) recites “providing observer data,” step 1(c) recites “comparing at least a portion of said observer data,” and step 1(d) recites “combining … with said observer data.” The reason Infernal applies this construction is due to their infringement theory summarized below:

In its infringement theory, for step 1(a) Infernal refers to albedo (color data), normal vector, position, diffuse, depth, and other observer data; for step 1(c), Infernal refers to normal vector and position data; and for step 1(d), Infernal refers to only albedo data. Thus, Infernal’s infringement theory relies on applying different obverser data for steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d). Infernal argued that “said observer data” in step 1(d) can refer to a narrower set of data than “observer data” in step 1(a) because both independently meet the district court’s construction of “observer data.”

In analyzing Infernal’s argument, the CAFC stated the principal that “[in] grammatical terms, the instances of [‘said’] in the claim are anaphoric phrases, referring to the initial antecedent phrase” citing Baldwin Graphic Sys., Inc. v. Siebert, Inc., 512 F.3d 1338, 1342 (Fed. Cir. 2008). The CAFC further stated that based on this principle, the term “said observer data” recited in steps 1(c) and 1(d) must refer back to the “observer data” recited in step 1(a), and concluded that “the ‘observer data’ in step 1(a) must be the same “observer data” in steps 1(c) and 1(d).” The CAFC stated that this analysis applies even though the district court’s construction of “observer data” encompasses “at least color data.” In concluding that term “observer data” cannot refer to different data among steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d), the CAFC stated:

Although the initial “observer data” in step 1(a) includes data that is “at least color data,” the use of the word “said” indicates that each subsequent instance of “said observer data” must refer back to the same “observer data” initially referred to in step 1(a). An open-ended construction of “observer data” (“data representing at least the color of objects”) does not permit each instance of “observer data” in a claim to refer to an independent set of data.

Regarding the district court’s finding that Infernal failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact, Infernal argued that the district court erred in its finding that the accused video games cannot perform the claimed steps in the specified sequence. The district court held that Infernal failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact as to the accused games performing limitation 1(d): “combining … with said observer data.”

The CAFC agreed with the district court. Referring to Infernal’s infringement theory diagram, the CAFC stated that for step 1(a), Infernal identified “observer data” as albedo (color data), normal vector, position, diffuse, depth, and other observer data, but for step 1(d), Infernal identified “said observer data” as only albedo (color data). “Because it is undisputed that the mapping of the Accused Games’s ‘observer data’ in step 1(a) is different than the mapping of the “observer data” in step 1(d), … there is no genuine issue of material fact as to whether the Accused Games infringe [step 1(d)].” The CAFC also pointed out that Infernal’s mapping for step 1(d) improperly excludes data that is mapped to “a portion of said observer data” in step 1(c).

Comments

In a footnote, the CAFC stated that this analysis is consistent with other cases in which the use of the word “said” or “the” refers back to the initial limitation, “even when the initial limitation refers to one or more elements.” When drafting claims, if you intend for a later recitation of the same limitation to refer to an independent instance of the limitation, then you will need to modify the language rather than merely using “said” or “the.”

It appears that if step 1(d) in Infernal’s claim referred to “at least a portion of said observer data,” Infernal would have had a better argument that the observer data in step 1(d) can be a narrower data set than the “observer data” in step 1(a). The CAFC also pointed out that Infernal knew how to do this because that is what they did in step 1(c) and chose not to in step 1(d).

Obvious Claim Limitation Fails to Present Different Issues of Patentability Needed to Deny Collateral Estoppel

| February 16, 2023

Google LLC V. Hammond Development International, Inc.

Decided: December 8, 2022

Moore, Chen, and Stoll. Opinion by Moore.

Summary

On appeal from an inter partes review (IPR) decision finding some claims of a first patent not unpatentable over prior art, where counterpart claims of a related, second patent had been invalidated in another IPR decision, the CAFC found that the second IPR decision has collateral estoppel effect on certain challenged claims of the first patent where slight difference in claim language immaterial to the question of validity in the underlying decision does not present different issues of patentability.

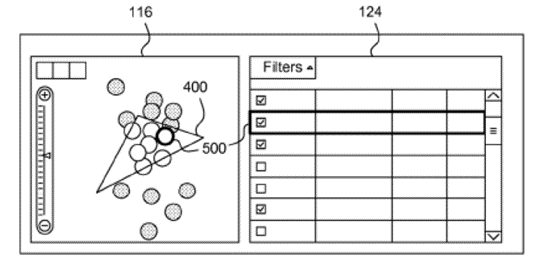

Details

Google filed IPR petitions against Hammond’s patents including U.S. Patent Nos. 10,270,816 (“’816 patent”) and No. 9,264,483 (“’483 patent”). Hammond’s challenged patents relate to a communication system that allows a communication device to remotely execute one or more applications. The specification shared by these patents discloses that the inventive system enables a user to check a bank account balance or airline flight status by using a cell phone or other communication devices to interact with application servers over a network, which in turn access database storing applications so as to perform the desired functionalities. As seen in Figs. 1A-1D, for example, the system may be implemented using a single application server or multiple application servers.

In the ‘816 IPR, Google challenged all the claims of the patent, asserting different prior art combinations against different subsets of claims. Relevant to this case are obviousness challenges of claims 1, 14 and 18 which recite, among other things, one or both of two particular limitations referred to as first[1] and second[2] “request for processing service” limitations, as summarized below:

| Claims | “request for processing service” limitations recited | References/Basis |

| Independent claim 1 | Both first and second limitations | Gilmore, Dhara, and Dodrill |

| Independent claim 14 | First limitation | Gilmore and Creamer |

| Claim 18 dependent from claim 14 | Second limitation | Gilmore, Creamer and Dodrill |

As to claim 1, Google asserted that Gilmore and Dodrill in combination would meet the first and second limitations. As to claim 14, however, Google did not rely on Dodrill for the first limitation in particular. Instead, Google included Dodrill solely to obviate the second limitation as recited in claim 18 dependent from claim 14.

The above choice of references caused trouble to Google. The Board, finding Gilmore and Dodrill in combination as teaching both the first and second limitations in claim 1, determined that the combination of Gilmore and Creamer would not do so with the first limitation as recited in claim 14. Further, Google’s assertion of invalidity as to dependent claim 18 also failed with the contrary finding of claim 14; even though Google did rely on Dodrill for the second limitation as recited in claim 18, that reliance did not extend to the first limitation in parent claim 14. On June 4, 2021, a final written decision was issued in the ‘816 IPR, determining that claims 1–13 and 20–30 would have been obvious, but not claim 14 and its dependent claims 15–19.

On April 12, 2021, prior to the ‘816 IPR decision, the ‘483 IPR had concluded in a final written decision invalidating all the challenged claims for obviousness over prior art including Gilmore and Dodrill. Among those invalidated claims was claim 18 of the ‘483 patent, which recites both the first and second “request for processing service” limitations as in claim 18 of the ‘816 patent.

Google appealed the IPR rulings on claims 14-19 of the ‘816 patent to the CAFC. Google asserted, among other things, that collateral estoppel effect of the invalidity determination of claim 18 of the ‘483 patent renders claim 18 of the ‘816 patent also unpatentable. Finding collateral estoppel as applicable to this case, the CAFC reversed as to claims 14 and 18, and affirmed as to claims 15-17 and 19.

No forfeiture of collateral estoppel

As a preliminary matter, the CAFC found that Google’s omission of its collateral estoppel argument in the IPR petition does not cause forfeiture. Since the issuance and the finality of the ‘483 final written decision took place only after Google’s filing of the ‘816 IPR petition, the argument based on non-existent preclusive judgement could not have been included in that petition. As such, the CAFC held that Google is allowed to raise its collateral estoppel argument for the first time on appeal.

Collateral estoppel – Identicality requirement

Noting that the collateral estoppel can apply in IPR proceedings, the CAFC recited the four requirements for the preclusive effect to exist under In re Freeman:

(1) the issue is identical to one decided in the first action; (2) the issue was actually litigated in the first action; (3) resolution of the issue was essential to a final judgment in the first action; and (4) [the party against whom collateral estoppel is being asserted] had a full and fair opportunity to litigate the issue in the first action.

Only the first element was disputed in the present case. Citing its precedents, the CAFC emphasized that the identicality requirement concerns identicality of “the issues of patentability” (emphasis original), rather than the claim language per se. As such, applicability of collateral estoppel is not affected by mere existence of slightly different wording used to depict a substantially identical invention so long as the differences between the patent claims “do not materially alter the question of invalidity,” which is “a legal conclusion based on underlying facts.”

Claim 18 – Invalid for collateral estoppel

The CAFC held that collateral estoppel applies so as to render the claim 18 of the ‘816 patent unpatentable because it shares identical issues of patentability with the invalidated claim 18 of the ’483 patent. Specifically, the CAFC noted that “only difference between the claims is the language describing the number of application servers”: The claim 18 of the ‘816 patent recites “a plurality of application servers” including “first one” and “second one” configured to perform certain respective functions specifically associated therewith, whereas the claim 18 of the ‘483 patent requires “one or more application servers” or “the at least one application server” to perform the requisite functionality. The CAFC found that the difference is immaterial to the question of invalidity in the collateral estoppel analysis, relying on the Board’s factual findings that the above limitation of claim 18 of the ‘816 patent would have been obvious to a skilled artisan, as supported by Google’s expert evidence, which were not challenged by Hammond on appeal.

Claim 14 – Invalid for invalidation of dependent claim 18

Having found claim 18 unpatentable, the CAFC went on to hold that independent claim 14, from which claim 18 depends, is also unpatentable. In so doing, the CAFC noted that the parties had agreed on the invalidity consequence of the parent claim based on the invalidated dependent claim[3]. In a footnote, the Opinion states that since Hammond failed to assert that Google’s collateral estoppel arguments should be limited to the references asserted in the petition, the impact of Google’s original invalidity challenge against claim 14—which does not use the same combination of references as claim 18—was not explored.

Claims 15-17 and 19 – Not unpatentable due to lack of collateral estoppel arguments

The CAFC distinguished the remaining claims from claim 18 and claim 14. Unlike claim 18, Google made no collateral estoppel arguments against claims 15-17 and 19. Rather, Google’s arguments as to these claims relied on the Board’s obviousness findings as to parallel dependent claims. Moreover, unlike claim 14, Hammad did not admit that invalidity of claim 18 is consequential to unpatentability of claims 15-17 and 19. As such, Google failed to meet its burden to provide convincing arguments for reversal on appeal.

Takeaway

This case depicts an interplay between collateral estoppel analysis on appeal and obviousness findings in underlying litigation: The identicality of the issues of patentability exists where the adjudicated and the unadjudicated claims are substantially the same with their only difference being a limitation that has been found as obvious. Parties in parallel actions involving patent claims of the same family may want to be mindful of potential impact of obviousness determination as to a claim limitation unique to one patent but not in the other in the future inquiry of collateral estoppel.

[1] Recited as “the application server is configured to transmit … a request for processing service … to the at least one communication device” in claim 1 of the ‘816 patent.

[2] Recited as “wherein the request for processing service comprises an instruction to present a user of the at least one communication device the voice representation” in claim 1 of the ‘816 patent.

[3] “[T]he patentability of claim 14 rises and falls with claim 18.” During oral argument, this principle was noted referring to Callaway Golf Co. v. Acushnet Co. (Fed. Cir., August 14, 2009).

CAFC splits the difference between VLSI and Intel on Claim Construction

| December 28, 2022

VLSI Technology LLC v. Intel Corp.

Decided: November 15, 2022

CHEN, BRYSON, and HUGHES. Opinion by Bryson

Summary:

The Court affirmed the PTAB’s claim construction which had narrowed an interpretation taken from the related District Court’s construction and remanded on a separate claim construction for reading a “used for” aspect out of the claim.

Background:

Intel filed three IPR’s against VLSI’s U.S. Patent No. 7,247,552 (“the ’552 patent”). The ’552 patent is directed to the structures of an integrated circuit that reduce the potential for damage to the interconnect layers and dielectric material when the chip is attached to another electronic component. The two representative claims were claim 1 directed to a device and claim 20 directed to a method. The terms subject to construction are emphasized below.

1. An integrated circuit, comprising:

a substrate having active circuitry;

a bond pad over the substrate;

a force region at least under the bond pad characterized by being susceptible to defects due to stress applied to the bond pad;

a stack of interconnect layers, wherein each interconnect layer has a portion in the force region; and

a plurality of interlayer dielectrics separating the interconnect layers of the stack of interconnect layers and having at least one via for interconnecting two of the interconnect layers of the stack of interconnect layers;

wherein at least one interconnect layer of the stack of interconnect layers comprises a functional metal line underlying the bond pad that is not electrically connected to the bond pad and is used for wiring or interconnect to the active circuitry, the at least one interconnect layer of the stack of interconnect layers further comprising dummy metal lines in the portion that is in the force region to obtain a predetermined metal density in the portion that is in the force region.

20. A method of making an integrated circuit having a plurality of bond pads, comprising:

developing a circuit design of the integrated circuit;

developing a layout of the integrated circuit according to the circuit design, wherein the layout comprises a plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers that extend under a first bond pad of the plurality of bond pads, at least a portion of the plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers underlying the first bond pad and not electrically connected to the bond pad as a result of being used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad;

modifying the layout by adding dummy metal lines to the plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers to achieve a metal density of at least forty percent for each of the plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers; and

forming the integrated circuit comprising the dummy metal lines.

VLSI had brought suit in the District of Delaware, charging Intel with infringing the ’552 patent. The District court construed the term “force region,” referencing the specification of the ’552 patent to mean a “region within the integrated circuit in which forces are exerted on the interconnect structure when a die attach is performed.” In the IPRs Intel proposed a construction of “force region” that was consistent with that adopted by the district court and VLSI did not oppose Intel’s proposed construction before the Board.

However, in the course of the IPR proceedings it became apparent that they disagreed as to the meaning of the term “die attach” as set forth in the District court construction.

Intel argued that the term “die attach” refers to any method of attaching the chip to another electronic component, and that the term “die attach” therefore includes attachment by a method known as wire bonding. VLSI argued that the term “die attach” refers to a method of attachment known as “flip chip” bonding, and does not include wire bonding.

The construction was paramount to claim 1 as applying its proposed restrictive definition of “die attach,” VLSI distinguished Intel’s principal prior art reference for the “force region” limitation, U.S. Patent Publication No. 2004/0150112 (“Oda”). Oda discloses attaching a chip to another component using wire bonding but not the flip chip process.

The Board sided with Intel that wire bonding is a type of die attach, and that Oda therefore disclosed a “force region”. Specifically, the Board found that the ’552 patent specification made clear in several places that the term “force region” was not limited to flip chip bonding, but could include wire bonding as well. Based on that finding, the Board concluded that Oda disclosed the “force region” element of claim 1 and was unpatentable for obviousness.

Regarding claim 20 of the ’552 patent, the parties disagreed over the construction of the limitation providing that the “metal-containing interconnect layers” are “used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad.” VLSI argued that the phrase requires a connection to active circuitry or the capability to carry electricity. Intel argued that the claim does not require that the interconnection actually carry electricity.

The Board again sided with Intel, asserting the principally relied upon U.S. Patent No. 7,102,223 (“Kanaoka”) teaches the “used for electrical interconnection” limitation. The Board cited to figure 45 of Kanaoka for its disclosure of a die that has a series of interconnect layers, some of which are connected to each other.

VLSI appealed.

CAFC Decision:

VLSI argued that the Board erred in its treatment of the “force region” limitation in claim 1 and in construing the phrase “used for electrical interconnection” in claim 20 to encompass a metallic structure that is not connected to active circuitry.

Claim 1

Regarding the “force region” limitation, VLSI argued that the Board failed to acknowledge and give appropriate weight to the district court’s claim construction. In particular, VLSI based its argument principally on the requirement that the Board “consider” prior claim construction determinations by a district court and give such prior constructions appropriate weight.

However, the CAFC found that the Board was clearly well aware of the district court’s construction, as it was the subject of repeated and extensive discussion in the briefing and in the oral hearing before the PTAB. Further, the Court found that the Board did not reject the district court’s construction, but rather the district court’s construction concealed a fundamental disagreement between the parties as to the proper construction of “force region.”

They held that although the district court defined the term “force region” with reference to “die attach” processes, the district court did not decide— and was not asked to decide—whether the term “die attach,” as used in the patent, included wire bonding or was limited to flip chip bonding. Thus, the CAFC found that the Board addressed an argument not made to the district court, and it reached a conclusion not at odds with the conclusion reached by the district court.

In reaching their decision, the Court noted that other language in the specification of the ‘552 patent indicates that the claimed “force region” is not limited to attachment processes that use flip chip bonding. Restating precedence that claims should not be limited “to preferred embodiments or specific examples in the specification,” they emphasized that even if the term “die attach,” was used in one section of the specification to refer to flip chip bonding in particular other portions of the specification did make clear that the invention was not intended to be limited to flip chip bonding.

VLSI further contended that defining “force region” to mean a region at least directly under the bond pad is legally flawed because the definition restates a requirement that is already in the claims. The Court noted that although caselaw has emphasized redundant construction should not be used, in this case intrinsic evidence makes it clear that the “redundant” construction is correct. Specifically, they stated that the “force region” limitation is best understood as containing a definition of the force region, (“… just as would be the case if the language of the limitation had read ‘a region, referred to as a force region, at least under the bond pad . . .’ or ‘a force region, i.e., a region at least under the bond pad . . . .’), and concluded that the language “is best viewed not as redundant, but merely as clumsily drafted.”

Additionally, VLSI argued the Board was bound by the district court’s and the parties’ agreed upon claim construction, regardless of whether the construction to which the parties agree is actually the proper construction of that term, citing the Supreme Court’s decision in SAS Institute v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct. 1348 (2018), and the CAFC’s decisions in Koninklijke Philips N.V. v. Google LLC, 948 F.3d 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2020), and In re Magnum Oil Tools International, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

The Court rejected VLSI’s interpretation of the precedent set by the cases. Instead, they noted that each of these cases in fact stands for the proposition that the petition defines the scope of the IPR proceeding and that the Board must base its decision on arguments that were advanced by a party and to which the opposing party was given a chance to respond. They affirmatively stated that none of the relied upon cases prohibits the Board from construing claims in accordance with its own analysis and may adopt its own claim construction of a disputed claim term. Specifically, as to the case at hand, they noted the parties’ very different understandings of the meaning of the term “die attach,” and that it was clear in the Board proceedings that there was no real agreement on the proper claim construction. They conclude that in such a situation, it was proper for the Board to adopt its own construction of a disputed claim term.

Based thereon, the Court affirmed the claim construction of “force region” and the PTAB’s application of the Oda prior art reference.

Claim 20

Regarding claim 20, VLSI argued that the Board erred in construing the phrase “used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad,”. As noted above, the Board had held that this phrase encompasses interconnect layers that are “electrically connected to each other but not electrically connected to the bond pad” or to any other active circuitry. VLSI asserted that under its proposed construction, the Kanaoka reference does not disclose the “used for electrical interconnection” limitation of claim 20, because the metallic layers are connected by the vias only to one another; they do not carry electricity and are not electrically connected to any other components.

The Court agreed with VLSI that the Board’s construction of the phrase “used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad” was too broad, noting that two aspects of the claim make this point clear. First, the use of the words “being used for” in the claim imply that some sort of actual use of the metal interconnect layers to carry electricity is required. Second, the recitation of “dummy metal lines” elsewhere in claim 20 implies that the claimed “metal-containing interconnect layers” are capable of carrying electricity; otherwise, there would be no distinction between the dummy metal lines and the rest of the interconnect layer. The Court further noted that the file history of the ’552 patent and amendments made during prosecution provided additional support for this conclusion.

Furthermore, they noted that the phrase “as a result of being used for electrical interconnection not directly to the bond pad” was meant to serve some purpose and should be construed to have some independent meaning, citing Merck & Co. v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., 395 F.3d 1364, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (“A claim construction that gives meaning to all the terms of the claim is preferred over one that does not do so.”). Thus, they concluded that the words “being used for” imply that the interconnect layers are at least capable of carrying electricity.

The Court therefore remanded the patentability determination of claim 20 to the Board to assess Intel‘s obviousness arguments in light of their new construction of the “used for electrical interconnection” limitation.

Take away

The PTAB is not hamstrung by prior claim construction reached in a District Court action. The Board may construe claims in accordance with its own analysis and may adopt its own claim construction of a disputed claim term.

The recitation of an operational function (“being used for”) in a claim should not be ignored in claim construction. The claim language should be taken as a whole and other aspects of the claim (“dummy metal lines”) which infer an interpretation should be considered.

No Shapeshifting Claims Through Argument in an IPR

| December 15, 2022

CUPP Computing AS v. Trend Micro Inc.

Decided: November 16, 2022

Circuit Judges Dyk, Taranto and Stark. Opinion by Dyk.

Summary:

CUPP appeals three inter partes review (“IPR”) decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”), largely due to an issue of claim construction. The three patents at issue are U.S. Patents Nos. 8,631,488 (“’488 patent”), 9,106,683 (“’683 patent”), and 9,843,595 (“’595 patent”). The contested claim construction involves the limitation concerning a “security system processor,” which appears in every independent claim in each of the three patents.

The limitation in question reads in part “the mobile device having a mobile device processor different than the mobile security system processor”.

Trend Micro petitioned the Board for inter partes review of several claims in the ’488, ’683, and ’595 patents, arguing that the claims were unpatentable as obvious over two individual prior art references. CUPP responded that the security system processor limitation required that the security system processor be “remote” from the mobile device processor, and that neither of the cited references disclosed this limitation because both taught a security processor bundled within a mobile device.

The Board instituted review and, in three final written decisions, found all the challenged claims obvious over the prior art. Specifically, the Board held that the challenged claims did not require that the security system processor be remote from the mobile device processor, but merely that the mobile device has a mobile device processor different than the mobile security system processor.

That is, the fact that the security system processor is “different” than the mobile device processor does not suggest that the two processors are remote from one another. Rather, citing Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, the Board and the CAFC noted that the ordinary meaning of “different” is simply “dissimilar.” The CAFC further noted that CUPP had given no reason to apply a more specialized meaning to the word.

Furthermore, the CAFC drew support from the specification of each of the three Patents. Briefly, that in one “preferred embodiment” each of the patents described that the mobile security system may be incorporated within the mobile device. Thus, the CAFC concluded that “highly persuasive” evidence would be required to read claims as excluding a preferred embodiment of the invention. Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576, 1583–84 (Fed. Cir. 1996). Indeed, “a claim interpretation that excludes a preferred embodiment from the scope of the claim is rarely, if ever, correct.” Accent Pack-aging, Inc. v. Leggett & Platt, Inc., 707 F.3d 1318, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (citation omitted).

CUPP responds that, because at least one independent claim in each of the patents requires the security system to send a signal “to” the mobile device, and “communicate with” the mobile device, the system must be remote from the mobile device processor.

The CAFC were not persuaded holding that the Board properly construed the security system processor limitation in line with the specification. The CAFC analogized that “just as a person can send an email to him- or herself, a unit of a mobile device can send a signal “to,” or “communicate with,” the device of which it is a part.”

Next, CUPP argued that, because it disclaimed a non-remote security system processor during the initial examination of one of the patents at issue, the Board’s construction is erroneous. The CAFC held that the Board properly rejected that argument, because CUPP’s disclaimer did not unmistakably renounce security system processors embedded in a mobile device. Rather, the CAFC upheld the Board’s reading of CUPP’s remarks during prosecution as a “reasonable interpretation[]” that defeats CUPP’s assertion of prosecutorial disclaimer. Avid Tech., Inc., 812 F.3d at 1045 (citation omitted); see also J.A. 20–22.

Briefly, during prosecution of the ’683 patent, the Patent Office examiner found all claims in the application obvious in light of the prior art. CUPP’s responded that if the TPM “were implemented as a stand-alone chip attached to a PC mother-board,” it would be “part of the motherboard of the mobile devices” rather than being a separate processor. J.A. 3578. The TPM would therefore not constitute “a mobile security system processor different from a mobile system processor.”

The Board found, and the CAFC upheld, that under one plausible reading, CUPP’s point was that the prior art failed to teach different processors because the TPM lacks a distinct processor. Thus, under this interpretation, if the TPM were “a stand-alone chip attached to a . . . motherboard,” it would rely on the motherboard’s processor, and not have its own different processor. For this reason, the CAFC concluded that CUPP’s comment to the examiner is consistent with it retaining claims to security system processors embedded in a mobile device with a separate processor.

Lastly, CUPP contended that the Board erred by rejecting CUPP’s disclaimer in the IPRs themselves, disavowing a security system processor embedded in a mobile device.

Here, the CAFC unambiguously stated that it was making “precedential the straightforward conclusion [they] drew in an earlier nonprecedential opinion: “[T]he Board is not required to accept a patent owner’s arguments as disclaimer when deciding the merits of those arguments.” VirnetX Inc. v. Mangrove Partners Master Fund, Ltd., 778 F. App’x 897, 910 (Fed. Cir. 2019). That a rule permitting a patentee to tailor its claims in an IPR through argument alone would substantially undermine the IPR process. Congress designed inter partes review to “giv[e] the Patent Office significant power to revisit and revise earlier patent grants,” thus “protect[ing] the public’s paramount interest in seeing that patent monopolies are kept within their legitimate scope.” If patentees could shapeshift their claims through argument in an IPR, they would frustrate the Patent Office’s power to “revisit” the claims it granted, and require focus on claims the patentee now wishes it had secured. See also Oil States Energy Servs., LLC v. Greene’s Energy Grp., LLC, 138 S. Ct. 1365, 1373 (2018).

Thus, to conclude, a disclaimer in an IPR proceeding is only binding in later proceedings, whether before the PTO or in court. The CAFC emphasized that congress created a specialized process for patentees to amend their claims in an IPR, and CUPP’s proposed rule would render that process unnecessary because the same outcome could be achieved by disclaimer. See 35 U.S.C. § 316(d).

Take-away:

- A disclaimer in an IPR proceeding is only binding in later proceedings, whether before the PTO or in court.

- A claim interpretation that excludes a preferred embodiment from the scope of the claim is rarely, if ever, correct.

- Disclaimers made during prosecution must be clear and unmistakable to be relied upon later. Specifically: “The doctrine of prosecution disclaimer precludes patentees from recapturing through claim interpretation specific meanings disclaimed during prosecution.” Mass. Inst. of Tech. v. Shire Pharms., Inc., 839 F.3d 1111, 1119 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (ellipsis, alterations, and citation omitted). However, a patentee will only be bound to a “disavowal [that was] both clear and unmistakable.” Id. (citation omitted). Thus, where “the alleged disavowal is ambiguous, or even amenable to multiple reasonable interpretations, we have declined to find prosecution disclaimer.” Avid Tech., Inc. v. Harmonic, Inc., 812 F.3d 1040, 1045 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- Claim terms are given their ordinary meaning unless persuasive reason is provided to apply a more specialized meaning to the word.

MERE AUTOMATION OF MANUAL PROCESSES USING GENERIC COMPUTERS DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A PATENTABLE IMPROVEMENT IN COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY

| December 6, 2022

International Business Machines Corporation v. Zillow Group, Inc., Zillow, Inc.

Decided: October 17, 2022

Hughes (author), Reyna, and Stoll (dissenting in parts)

Summary:

In 2019, IBM sued Zillow for infringement of several patents related to graphical display technology in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington. Zillow filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings, arguing that the claims of IBM’s asserted patents were patent ineligible under § 101. The district court granted Zillow’s motion as to two IBM patents because they were directed to abstract ideas with no inventive concept. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court decision and therefore, affirmed.

Details:

Two asserted IBM patents are U.S. Patent Nos. 9,158,789 (“the ’789 patent”) and 7,187,389 (“the ’389 patent”).

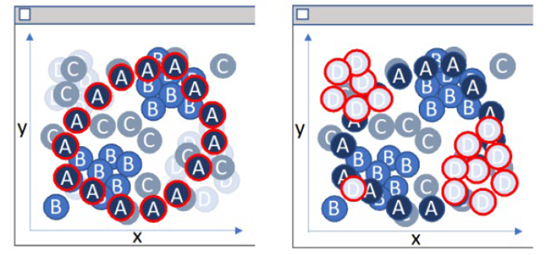

The ’789 patent

This patent describes a method for “coordinated geospatial, list-based and filter-based selection.” Here, a user draws a shape on a map to select that area of the map, and the claimed system then filters and displays data limited to that area of the map.

Claim 8 is a representative claim:

A method for coordinated geospatial and list-based mapping, the operations comprising:

presenting a map display on a display device, wherein the map display comprises elements within a viewing area of the map display, wherein the elements comprise geospatial characteristics, wherein the elements comprise selected and unselected elements;

presenting a list display on the display device, wherein the list display comprises a customizable list comprising the elements from the map display;

receiving a user input drawing a selection area in the viewing area of the map display, wherein the selection area is a user determined shape, wherein the selection area is smaller than the viewing area of the map display, wherein the viewing area comprises elements that are visible within the map display and are outside the selection area;

selecting any unselected elements within the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area and deselecting any selected elements outside the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area; and

synchronizing the map display and the list display to concurrently update the selection and deselection of the elements according to the user input, the selection and deselection occurring on both the map display and the list display.

The ’389 patent

This patent describes methods of displaying layered data on a spatially oriented display based on nonspatial display attributes (i.e., displaying objects in visually distinct layers). Here, objects in layers of interest could be emphasized while other layers could be deemphasized.

Claim 1 is a representative claim:

A method of displaying layered data, said method comprising:

selecting one or more objects to be displayed in a plurality of layers;

identifying a plurality of non-spatially distinguishable display attributes, wherein one or more of the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponds to each of the layers;

matching each of the objects to one of the layers;

applying the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponding to the layer for each of the matched objects;

determining a layer order for the plurality of layers, wherein the layer order determines a display emphasis corresponding to the objects from the plurality of objects in the corresponding layers; and

displaying the objects with the applied non-spatially distinguishable display attributes based upon the determination, wherein the objects in a first layer from the plurality of layers are visually distinguished from the objects in the other plurality of layers based upon the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes of the first layer.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reviewed the grant of a Rule 12 motion under the law of the regional circuit (de novo for the Ninth Circuit).

As for Alice step one analysis of the ’789 patent, the Federal Circuit held that the claims fail to recite any inventive technology for improving computers as tools, and instead directed to “an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool.”

The Federal Circuit further held that identifying, analyzing, and presenting any data to a user is not an improvement specific to computer technology, and that mere automation of manual processes using generic computers is not a patentable improvement in computer technology.

The Federal Circuit held that this patent describes functions (presenting, receiving, selecting, synchronizing) without explaining how to accomplish these functions.

As for Alice step two analysis of the ’789 patent, the Federal Circuit noted that IBM has not made any allegations that any features of the claims is inventive. Instead, the Federal Circuit held that the limitations in this patent simply describe the abstract method without providing more.

As for Alice step one analysis of the ’389 patent, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that this patent is directed to the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information (merely organize and arrange sets of visual information into layers and present the layers on a generic display device).

The Federal Circuit held that like the ’789 patent, this patent describes various functions without explaining how to accomplish any of them.

The Federal Circuit further held that the problem this patent tries to solve is not even specific to a computing environment, and the solution that this patent provides could be accomplished using colored pencils and translucent paper.

As for Alice step two analysis of the ’389 patent, the Federal Circuit noted that dynamic re-layering or rematching could also be done by hand (slowly), and that any of the patent’s improved efficiency does not come from an improvement in the computer but from applying the claimed abstract idea to a computer display.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit held that there is no inventive concept that transforms the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information into a patent-eligible application of that abstract idea.

Dissent by Stoll

Judge Stoll agreed with the majority opinion. However, she did not agree with the majority opinion that claims 9 and 13 of the ’389 patent are not patent eligible.

The information handling system as described in claim 8 further comprising:

a rearranging request received from a user;

rearranging logic to rearrange the displayed layers, the rearranging logic including:

re-matching logic to re-match one or more objects to a different layer from the plurality of layers;

application logic to apply the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponding to the different layer to the one or more re-matched objects; and

display logic to display the one or more rematched objects.

She noted that in combination with factual allegations in the complaint (problems with the conventional technology with larger and complex data systems) and the expert declaration, the claimed relaying and rematching steps are directed to a technical improvement in how a user interacts with a computer with the GUI.

Takeaway:

- The argument that the claimed invention improves a user’s experience while using a generic computer is not sufficient to render the claims patent eligible at Alice step one analysis.

- Identifying, analyzing, and presenting certain data to a user is not an improvement specific to computing technology itself (mere automation of manual processes using generic computers not sufficient).

- The specification should be drafted to explain how to accomplish the required functions instead of merely describing them (avoid “result-based functional language”).

Tags: 35 U.S.C. §101 > Alice > patent eligible subject matter > patent ineligible subject matter

Throwing in Kitchen Sink on 101 Legal Arguments Didn’t Help Save Patent from Alice Ax

| November 21, 2022

In Re Killian

Taranto, Clevenger, Chen (August 23, 2022).

Summary:

Killian’s claim to “determining eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance [SSDI] benefits through a computer network” was deemed “clearly patent ineligible in view of our precedent.” However, the Federal Circuit also disposes of a host of the appellant’s legal challenges to 101 jurisprudence, including:

(A) all court and Board decisions finding a claim patent ineligible under Alice/Mayo is arbitrary and capricious under the APA;

(B) comparing this case to other cases in which this court and the Supreme Court considered issues of patent eligibility under 101 violates the appellant’s due process rights because Mr. Killian had no opportunity to appear in those other cases;

(C) the search for an “inventive concept” at Alice Step 2 is improper because Congress did away with an “invention” requirement when it enacted the Patent Act of 1952;

(D) “mental steps” ineligibility has no foundation in modern patent law; and

(E) there is no substantial evidence to support the rejections in view of the PTAB’s “evidentiary vacuum” in assessing the factual inquiry into whether the claimed process is well-understood, routine, and conventional.

Procedural History:

The PTAB’s affirmance of the examiner’s final rejection of Killian’s US Patent Application No. 14/450,024 under 35 USC §101 was appealed to the Federal Circuit and was upheld.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 is as follows:

A computerized method for determining eligibility for social security disability insurance (SSDI) benefits through a computer network, comprising the steps of:

(a) providing a computer processing means and a computer readable media;

(b) providing access to a Federal Social Security database through the computer network, wherein the Federal Social Security database provides records containing information relating to a person’s status of SSDI and/or parental and/or marital information relating to SSDI benefit eligibility;

(c) selecting at least one person who is identified as receiving treatment for developmental disabilities and/or mental illness;

(d) creating an electronic data record comprising information relating to at least the identity of the person and social security number, wherein the electronic data record is recorded on the computer readable media;

(e) retrieving the person’s Federal Social Security record containing information relating to the person’s status of SSDI benefits;

(f) determining whether the person is receiving SSDI benefits based on the SSDI status information contained within the Federal Social Security database record through the computer network; and

(g) indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is receiving SSDI benefits or is not receiving SSDI benefits.

The court agreed with the PTAB that the thrust of this claim is “the collection of information from various sources (a Federal database, a State database, and a caseworker) and understanding the meaning of that information (determining whether a person is receiving SSDI benefits and determining whether they are eligible for benefits under the law).” Collecting information and “determining” whether benefits are eligible are mental tasks humans routinely do. That these steps are performed on a generic computer or “through a computer network” does not save these claims from being directed to an abstract idea under Alice step 1. Under Alice step 2, this is merely reciting an abstract idea and adding “apply it with a computer.” The claims do not recite any technological improvement in how a computer goes about “determining” eligibility for benefits. Merely comparing information against eligibility requirements is what humans seeking benefits would do with or without a computer.

The court also addresses appellant’s further challenges (A)-(E) as follows.

- all court and Board decisions finding a claim patent ineligible under Alice/Mayo is arbitrary and capricious under the APA

The standards of review in the APA do not apply to decisions by courts. The APA governs judicial review of “agency action.”

There was also an assertion that there is a Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause violation stemming from the imprecision of the Alice/Mayo standard. However, the court noted that Killian never argued that the Alice/Mayo standard runs afoul of the “void-for-vagueness doctrine” and could not have argued this because this case was not even a close call (vagueness as applied to the particular case is a prerequisite to establishing facial vagueness).

As for Board decisions finding patents ineligible as being arbitrary and capricious under the APA, “we may not announce that the Board acts arbitrarily and capriciously merely by applying binding judicial precedent.” This would be akin to using the APA to attack the Supreme Court’s interpretations of 101. However, “the APA does not empower us to review decisions of ‘the courts of the United States’ because they are not agencies.”

Mr. Killian also requested “a single non-capricious definition or limiting principle” for “abstract idea” and “inventive concept.” However, the court points out that there is “no single, hard-and-fast rule that automatically outputs an answer in all contexts” because there are different types of abstract ideas (mental processes, methods of organizing human activity, claims to results rather than a means of achieving the claimed result). Nevertheless, guidance has been provided (citing several cases).

And even if the Alice/Mayo framework is unclear, “both this court and the Board would still be bound to follow the Supreme Court’s §101 jurisprudence as best we can as we must follow the Supreme Court’s precedent unless and until it is overruled by the Supreme Court.”

- comparing this case to other cases in which this court and the Supreme Court considered issues of patent eligibility under 101 violates the appellant’s due process rights because Mr. Killian had no opportunity to appear in those other cases

Examination of and comparison to earlier caselaw is just classic common law methodology for deciding cases arising under 101. “Nothing stops Mr. Killian from identifying any important distinctions between his claimed invention and claims we have analyzed in prior cases.”

- the search for an “inventive concept” at Alice Step 2 is improper because Congress did away with an “invention” requirement when it enacted the Patent Act of 1952

First, Killian has not established that Alice Step 2’s “inventive concept” is the same thing as the “invention” requirement in the Patent Act of 1952. It is not. For instance, there is no requirement to ascertain the “degree of skill and ingenuity” possessed by one of ordinary skill in the art under Alice Step 2. In any event, the Supreme Court required the “inventive concept” inquiry at Step 2, and so, “search for an inventive concept we must.”

- “mental steps” ineligibility has no foundation in modern patent law

“This argument is plainly incorrect” (citing Benson, Mayo, Diehr, Bilski, etc.). “[W]e are bound by our precedential decisions holding that steps capable of performance in the human mind are, without more, patent-ineligible abstract ideas.”

- there is no substantial evidence to support the rejections in view of the PTAB’s “evidentiary vacuum” in assessing the factual inquiry into whether the claimed process is well-understood, routine, and conventional

Substantial evidence supported the PTAB’s decision regarding Alice Step 2. The additional elements of a computer processor and a computer readable media are generic, as the application itself admits (the PTAB cited to the specification’s description about how the claimed method “may be performed by any suitable computer system”). And, the claimed “creating an electronic data record,” “indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is receiving SSDI adult child benefits,” “providing a caseworker display system,” “generating a data collection input screen,” “indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is eligible for SSDI adult child benefits,” and other data tasks are merely selection and manipulation of information – are not a transformative inventive concept.

Mr. Killian also refers to 55 documents allegedly presented to the examiner and the PTAB. But, because these were not included in the joint appendix and nothing is explained on appeal as to what these 55 documents show, “Mr. Killian forfeited any argument on appeal based on those fifty-five documents by failing to present anything more than a conclusory, skeletal argument.”

Takeaways:

Given the continued dissatisfaction over the court’s eligibility guidance and the frustration over the Supreme Court’s refusal to take on §101 since Alice, this decision offers a rare insight into the court’s position on various §101 legal challenges. For instance, this decision appears to suggest a potential Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause violation stemming from the imprecision of the Alice/Mayo standard, but only for a “close call” case where vagueness can be established for the particular case, in order to challenge the facial vagueness of the Alice/Mayo standard under the “void-for-vagueness doctrine.”

The Testimony of an Expert Without the Requisite Experience Would Be Discounted in the Obviousness Determination

| October 21, 2022

Best Medical International, Inc., v. Elekta Inc.

Before HUGHES, LINN, and STOLL, Circuit Judges. STOLL, Circuit Judge.

Summary

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s determination that challenged claims are unpatentable as obvious over the prior art.

Background

Best Medical International, Inc (BMI) owns the patent at issue, U.S. Patent No. 6,393,096 (‘096). Patent ‘096 is directed to a medical device and method for applying conformal radiation therapy to tumors using a pre-determined radiation dose. The device and the method are intended to improve radiation therapy by computing an optimal radiation beam arrangement that maximizes radiation of a tumor while minimizing radiation of healthy tissue. Claim 43 is listed below as representative of the claims:

43. A method of determining an optimized radiation beam arrangement for applying radiation to at least one tumor target volume while minimizing radiation to at least one structure volume in a patient, comprising the steps of:

distinguishing each of the at least one tumor target volume and each of the at least one structure volume by target or structure type;

determining desired partial volume data for each of the at least one target volume and structure volume associated with a desired dose prescription;