Insufficient Extrinsic Evidence and Prosecution Disclaimer Led to Claim Construction in Patentee’s Favor

| May 6, 2022

Decided: April 1, 2022

Newman, Reyna, and Stoll. Opinion by Reyna.

Summary

The CAFC found in favor of a patentee seeking broad interpretation of a claim term, where an expert testimony offered by an opponent in support of narrower claim scope was insufficient to overcome a clear record of the patent, and the prosecution history lacked “clear and unmistakable” statements to establish express disavowal of claim scope.

Details

This is an appeal from a district court action where Genuine Enabling Technology LLC (“Genuine”) sued Nintendo Co., Ltd. and Nintendo of America, Inc. (“Nintendo”) for infringing certain claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,219,730. The patent relates to user input devices, such as mouse and keyboard, and its representative claim 1 recites:

1. A user input apparatus operatively coupled to a computer via a communication means additionally receiving at least one input signal, comprising:

user input means for producing a user input stream;

input means for producing the at least one input signal;

converting means for receiving the at least one input signal and producing therefrom an input stream; and

encoding means for synchronizing the user input stream with the input stream and encoding the same into a combined data stream transferable by the communication means.

(Emphasis added.)

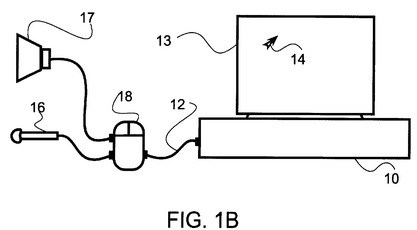

The inventive idea may be pictured as a “voice mouse.” As seen in Fig. 1B of the patent, the inventive apparatus or mouse 18, connected with a computer 10 via a communication link 12, serves the traditional function of allowing user to move an object 14 on the computer monitor 13 (i.e., “user input means for producing a user input stream”), while also capable of receiving a speech input from a microphone 16 (i.e., “input means for producing the at least one input signal”) and transmitting a speech output to a speaker 17.

At issue in the case is the construction of the term “input signal.”

During prosecution, the inventor distinguished his invention over U.S. Patent No. 5,990,866 (“Yollin”) cited in an office action, arguing that the “input signal” limitation was missing in the reference. Specifically, the inventor argued that various physiological sensors disclosed in Yollin, such as those detecting user’s muscle movement, heart rate, brain activity, blood pressure, skin temperature, etc., only produce “slow varying” signals as opposed to “signals containing audio or higher frequencies” to which his invention pertains. The inventor pointed out that the inventive apparatus would resolve a specific problem presented by the use of high frequency signals, which, unlike slow varying signals, tend to “collide” with other signals in producing a composite data stream. This “slow varying” vs. “audio or higher frequencies” distinction is repeatedly noted in the inventor’s argument.

The parties disputed the extent of prosecution disclaimer resulting from the inventor’s statements as to the term “input signal.” In the district court, Genuine proposed to construe the term as

“a signal having an audio or higher frequency,”

whereas Nintendo maintained that the proper scope should be narrower:

“A signal containing audio or higher frequencies. [The inventor] disclaimed signals that are 500 Hertz (Hz) or less. He also disclaimed signals that are generated from positional change information, user selection information, physiological response information, and other slow-varying information. Alternatively, indefinite.”

Nintendo argued that the inventor disclaimed the certain types of “slow-varying” signals taught by Yollin. While specific frequencies were not disclosed in Yollin, Nintendo relied on its expert testimony citing a reference purportedly showing that Yollin’s physiological sensors encompassed the range of “at least 500 Hz.”

Genuine contended that the disclaimed scope should be limited to “slow-varying signals below the audio frequency spectrum [of 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz],” in accordance with the inventor’s argument which only had distinguished the reference “slow-varying” signals from “fast-varying” signals.

The district court sided with Nintendo, finding non-infringement in its favor. In particular, the district court noted that “an applicant’s argument that a prior art reference is distinguishable on a particular ground can serve as a disclaimer of claim scope even if the applicant distinguishes the reference on other grounds as well.” Andersen Corp. v. Fiber Composites, LLC, 474 F.3d 1361, 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2007). That is, according to the district court, the fact that the inventor’s argument distinguished Yollin as lacking “audio or higher frequencies” did not negate the effect of the inventor’s statement also distinguishing Yollin’s range as “slow-varying” signals.

On appeal, the CAFC rejected the district court’s claim construction.

First, the CAFC noted that the role of extrinsic evidence in claim construction is limited, and cannot override intrinsic evidence where there is clear written record of the patent. And as one form of extrinsic evidence, “expert testimony may not be used to diverge significantly from the intrinsic record.” Here, the 500 Hz frequency threshold was not identified in the intrinsic record nor Yollin, and its only basis was Nintendo’s expert testimony which relied on another extrinsic reference that was not in the record. The extrinsic evidence conflicted with the prosecution history in which the examiner had accepted the inventor’s argument distinguishing Yollin without drawing a bright line between “slow-varying” and “audio or higher frequenc[y]” signals. As such, the CAFC found that the expert testimony cannot overcome the clarity of the intrinsic evidence.

Second, the CAFC noted that prosecution disclaimer requires that the patentee make a “clear and unmistakable” statement to disavow claim scope during prosecution. The fact that the inventor repeatedly distinguished the reference “slow-varying” signals from “audio or higher frequenc[y]” signals—the argument which successfully traversed the rejection—led the CAFC to decide that the “clear and unmistakable” disavowal was limited to “signals below the audio frequency spectrum.” Although the CAFC noted that the inventor’s statements “may implicate” certain frequency ranges such as 500 Hz or less, the intrinsic record was not unambiguous enough for the particular range to be disclaimed. For similar reasons, the CAFC also found no disclaimer of “signals that are generated from positional change information, user selection information, physiological response information, and other slow-varying information,” which had not been directly addressed in the inventor’s argument.

The CAFC concluded that the district court erred in the claim construction and that the proper scope of the term “input signal” is “a signal having an audio or higher frequency.”

Takeaway

This case provides a reminder that caution should be taken not to make “clear and unmistakable” statements in arguing around the prior art during prosecution. Although there appears to be no fixed criteria for assessing what qualifies as a “clear and unmistakable” disavowal, applicant’s consistency in presenting one main argument—focused on an essential distinction between the claim and the prior art—without introducing unnecessary details may help limit the extent of potential prosecution disclaimer.

DOCTRINE OF PROSECUTION DISCLAIMER ENSURES THAT CLAIMS ARE NOT CONSTRUED ONE WAY TO GET ALLOWANCE AND IN A DIFFERENT WAY TO AGAINST ACCUSED INFRINGERS

| July 8, 2021

SpeedTrack, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc. et al.

Decided on June 3, 2021

Prost (author), Bryson, and Reyna

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s claim construction orders regarding the hierarchical limitations recited in the SpeedTrack’s ’360 patent based on Applicants’ arguments and claim amendments made during the prosecution of the ’360 patent.

Details:

The ’360 patent

SpeedTrack owns U.S. Patent No. 5,544,360 (“the ’360 patent), which is directed to providing “a computer filing system for accessing files and data according to user-designated criteria.” The ’360 patent discusses that prior-art systems “employ a hierarchical filing structure” which could be very cumbersome when the number of files are large or file categories are not well-defined. In addition, the ’360 patent discusses that some prior-art systems are subject to errors when search queries are mistyped and restricted by the field of each data element and the contents of each field.

However, the ’360 patent discloses a method that uses “hybrid” folders, which “contain those files whose content overlaps more than one physical directory,” for providing freedom from the restrictions caused by hierarchical and other computer filing systems.

Representative claim 1 recites a three-step method: (1) creating a category description table containing category descriptions (having no predefined hierarchical relationship with such list or each other); (2) creating a file information directory as the category descriptions are associated with files; and (3) creating a search filter for searching for files using their associated category descriptions.

1. A method for accessing files in a data storage system of a computer system having means for reading and writing data from the data storage system, displaying information, and accepting user input, the method comprising the steps of:

(a) initially creating in the computer system a category description table containing a plurality of category descriptions, each category description comprising a descriptive name, the category descriptions having no predefined hierarchical relationship with such list or each other;

(b) thereafter creating in the computer system a file information directory comprising at least one entry corresponding to a file on the data storage system, each entry comprising at least a unique file identifier for the corresponding file, and a set of category descriptions selected from the category description table; and

(c) thereafter creating in the computer system a search filter comprising a set of category descriptions, wherein for each category description in the search filter there is guaranteed to be at least one entry in the file information directory having a set of category descriptions matching the set of category descriptions of the search filter.

District Court

In September of 2009, SpeedTrack sued retail website operations for infringement of the ’360 patent. The Northern District construed the hierarchical limitation with the below construction (relied in part on disclaimers made during prosecution):

The category descriptions have no predefined hierarchical relationship. A hierarchical relationship is a relationship that pertains to hierarchy. A hierarchy is a structure in which components are ranked into levels of subordination; each component has zero, one, or more subordinates; and no component has more than one superordinate component.

After that, SpeedTrack moved to clarify the district court’s construction regarding prosecution-history disclaimer.

Subsequently, the district court issued a second claim construction order by adding the following clarification in its first order:

Category descriptions based on predefined hierarchical field-and-value relationships are disclaimed. “Predefined” means that a field is defined as a first step and a value associated with data files is entered into the field as a second step. “Hierarchical relationship” has the meaning stated above. A field and value are ranked into levels of subordination if the field is a higher-order description that restricts the possible meaning of the value, such that the value must refer to the field. To be hierarchical, each field must have zero, one, or more associated values, and each value must have at most one associated field.

In order to support its second claim construction order, the district court analyzed SpeedTrack’s prosecution statements (for their clear disavowal of category descriptions based on hierarchical field-and-value relationships).

The Federal Circuit

The CAFC handled the issue of claim construction.

SpeedTrack acknowledged that the hierarchical limitation was added during the prosecution of the ’360 patent to overcome the Schwartz reference.

During the prosecution, Applicants distinguished their invention from Schwartz by arguing that “unlike prior art hierarchical filing systems, the present invention does not require the 2-part hierarchical relationship between fields or attributes, and associated values for such fields or attributes.”

In addition, Applicants argued that “the present invention is a non-hierarchical filing system that allows essentially ‘free-form’ association of category descriptions to files without regard to rigid definitions of distinct fields containing values.”

Finally, Applicants argued that “this distinction has been clarified in the claims as amended by the addition of the following language in all of the claims: ‘each category description comprising a descriptive name, the category descriptions having no predefined hierarchical relationships with such list or each other.’”).

The CAFC agreed with the district court’s assessment that predefined field-and-value relationships are excluded from the claims.

The CAFC disagreed with SpeedTrack’s argument that the “category descriptions” of the ’360 patent are not the fields of Schwartz and that the hierarchical limitation precludes predefined hierarchical relationships only among category descriptions.

SpeedTrack argued that Applicants distinguished Schwartz on other grounds. However, the CAFC did not agree with this argument.

In addition, the CAFC noted that SpeedTrack’s position contradicts its other litigation statements. “Ultimately, the doctrine of prosecution disclaimer ensures that claims are not ‘construed one way in order to obtain their allowance and in a different way against accused infringers.’” Aylus Networks, Inc. v. Apple Inc., 856 F.3d 1353, 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (quoting Southwall Techs., Inc. v. Cardinal IG Co., 54 F.3d 1570, 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1995)).

Finally, the CAFC noted that both of the first and second construction orders acknowledged the disclaimer.

Therefore, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s final judgement of noninfringement.

Takeaway:

- Applicants need to be careful about claim amendments and arguments made during the prosecution of their patents.

- Litigation statements, while not inventors’ prosecution statements and do not demonstrate prosecution-history disclaimer, can strengthen the court’s reasonings on the prosecution history.

Statements made in IPR proceeding can be relied on to support a finding of prosecution disclaimer during claim construction

| July 5, 2017

Aylus Networks, Inc., v. Apple Inc.

May 11, 2017

Before Moore, Linn, and Stoll. Opinion by Stoll.

Summary

Patent owner Aylus Networks, Inc. sued Apple Inc. in district court for infringement of the U.S. Patent No. RE 44,412 (“the ‘412 patent”). Apple filed two separate IPRs challenging validity of all the claims. PTAB denied to institute claim 2 based on Aylus’s explanation of a limitation to claim 2. During claim construction in district court, this same explanation is relied on to support a finding of prosecution disclaimer. CAFC affirmed the district court’s finding of prosecution history disclaimer. CAFC also stated that prosecution disclaimer applies whether a statement is made before or after instituting an IPR.

Clear and Unmistakeable Evidence of a Disclaimer Found in Response to Enablement Rejection

| April 24, 2013

Biogen Idec, Inc., et al. v. GlaxoSmithKline LLC, et al.

April 16, 2013

Panel: Dyk, Plager, Reyna. Opinion by Reyna. Dissent by Plager.

Summary

During prosecution of the patent, applicants responded to the examiner’s enablement rejection, wherein they failed to challenge the examiner’s understanding of the crucial terms, and limited their invention to what the examiner believed their specification enabled. The CAFC affirmed the district court’s narrow claim interpretation of the term “anti-CD20 antibody” based on prosecution history disclaimer.

実施可能要件を満たしていないとして発せられた拒絶通知に対して、出願人は、審査官の理解に対して反論することなく、明細書により実施可能であると審査官が判断したものに発明を限定するような主張を行った。よって、「anti-CD20 antibody」という用語について、狭いクレーム解釈を容認した地裁の判断は誤りでなかったとCAFCは判示した。

Tags: claim construction > disclaimer > estoppel > prosecution disclaimer > prosecution history disclaimer > prosecution history estoppel

Divided Claim Construction Leads to Reversal of Jury Verdict Against Alleged Infringer

| April 17, 2013

Saffran v. Johnson & Johnson

April 4, 2013

Panel: Lourie, Moore, and O’Malley. Opinion by Lourie. Concurrence Opinions by Moore and O’Malley.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed a $482 million jury verdict against Cordis, a member of the Johnson & Johnson family. The reversal came as a result of the Federal Circuit’s significant narrowing of the district court’s construction of two key claim limitations. One claim term was narrowed because the Federal Circuit found that the patentee’s arguments made during prosecution of the asserted patent, for the purpose of distinguishing over cited prior art, amounted to prosecution disclaimer. Meanwhile, a structure identified in the specification by the patentee as the corresponding structure to a means-plus-function limitation was disregarded as such, because the specification failed to link the identified structure to the recited function with sufficient specificity.