Make Sure Patent Claims Do Not Contain an Impossibility

| March 12, 2021

Synchronoss Technologies, Inc., v. Dropbox, Inc.

February 12, 2021

PROST, REYNA and TARANTO

Summary

Synchronoss Technologies appealed the district court’s decisions that all asserted claims relating to synchronizing data across multiple devices are either invalid or not infringed. The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s judgments of invalidity under 35 U.S.C. § 112, paragraph 2, with respect to certain asserted claims due to indefiniteness. The Federal Circuit also found no error in the district court’s conclusion that Dropbox does not directly infringe by “using” the claimed system under § 271(a). Thus, the Federal Circuit affirmed on non-infringement.

Background

Synchronoss sued Dropbox for infringement of three patents, 6,757,696 (“’696 patent”), 7,587,446 (“’446 patent”), and U.S. Patent Nos. 6,671,757 (“’757 patent”), all drawn to technology for synchronizing data across multiple devices.

The ’446 patent discloses a “method for transferring media data to a network coupled apparatus.” The indefinite argument of Dropbox targets on the asserted claims that require “generating a [single] digital media file” that itself “comprises a directory of digital media files.” Synchronoss’s expert conceded that “a digital media file cannot contain a directory of digital media files.” But Synchronoss argued that a person of ordinary skill in the art “would have been reasonably certain that the asserted ’446 patent claims require a digital media that is a part of a directory because a file cannot contain a directory.” The district court rejected the argument as “an improper attempt to redraft the claims” and concluded that all asserted claims of the ’446 patent are indefinite.

The ’696 patent discloses a synchronization agent management server connected to a plurality of synchronization agents via the Internet. The asserted claims of the ‘696 patent all include the following six terms, “user identifier module,” “authentication module identifying a user coupled to the synchronization system,” “user authenticator module,” “user login authenticator,” “user data flow controller,” and “transaction identifier module.” The district court concluded that all claims in the ’696 patent are invalid as indefinite. The decision leaned on the technical expert’s testimony that all six terms are functional claim terms. The specification failed to describe any specific structure for carrying out the respective functions.

The asserted claim 1 of ‘757 patent recites “a system for synchronizing data between a first system and a second system, comprising …” The district court found that hardware-related terms appear in all asserted claims of ‘757 patent. The hardware-related terms include “system,” “device,” and “apparatus,” all that means the asserted claims could not cover software without hardware. Dropbox argued that it distributed the accused software with no hardware. The district court granted summary judgment of non-infringement in favor of Dropbox.

Discussion

i. The ‘446 Patent – Indefiniteness

The Federal Circuit noted that the claims were held indefinite in circumstances where the asserted claims of the ’446 patent are nonsensical and require an impossibility—that the digital media file contains a directory of digital media files. As a matter of law under § 112, paragraph 2, the claims are required to particularly point out and distinctly claim the invention. “The primary purpose of this requirement of definiteness of claim language is to ensure that the scope of the claims is clear so the public is informed of the boundaries of what constitutes infringement of the patent.” (MPEP 2173)

Synchronoss argued that a person of ordinary skill would read the specification to interpret the meaning of the media file. However, the Federal Circuit rejected the argument since Synchronoss’s proposal would require rewriting the claims and also stated that “it is not our function to rewrite claims to preserve their validity.”

ii. The ‘696 Patent – Indefiniteness

The ‘696 patent was focused on whether the claims at issue invoke § 112, paragraph 6. The Federal Circuit applied a two-step process for construing the term, 1. identify the claimed function; 2. determine whether sufficient structure is disclosed in the specification that corresponds to the claimed function.

However, the asserted claims were found not to detail what a user identifier module consists of or how it operates. The specification fails to disclose an “adequate” corresponding structure that a person of ordinary skill in the art would be able to recognize and associate with the corresponding function in the claim. The Federal Circuit held that the term “user identifier module” is indefinite and affirmed the district court’s decision that asserted claims are invalid.

iii. The ‘757 Patent – Infringement

The ‘757 patent is the only one focused on the infringement issue. Synchronoss argued that the asserted claims recite hardware not as a claim limitation but merely as a reference to the “location for the software.” However, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s founding that the hardware term limited the asserted claims’ scope.

The Federal Circuit explained that “Supplying the software for the customer to use is not the same as using the system.” Dropbox only provides software to its customer but no corresponding hardware. Thus, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s summary judgment of non-infringement.

Takeaway

- Make sure patent claims do not contain an impossibility

- Supplying software alone does not infringe claims directed to hardware.

- “Adequate” structures in the specification are required to support the functional terms in the claims.

District court’s construction of a toothbrush claim gets flossed

| January 14, 2021

Maxill Inc. v. Loops, LLC (non-precedential)

December 31, 2020

Before Moore, Bryson, and Chen (Opinion by Chen).

Summary

Construing a claim reciting an assembly of identifiably separate components, the Federal Circuit determines that a limitation associated with a claimed component pertains to the component before it is combined with the other components. The lower court’s summary judgment of non-infringement, based on a claim construction requiring assembly, is reversed.

Details

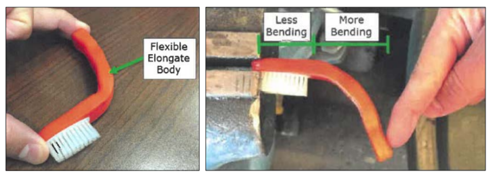

Loops, LLC and Loops Flexbrush, LLC (“Loops”) own U.S. Patent No. 8,448,285. The 285 patent is directed to a flexible toothbrush that is safe for distribution in correctional and mental health facilities. The toothbrush being made of flexible elastomers is less likely to be fashioned into a shiv.

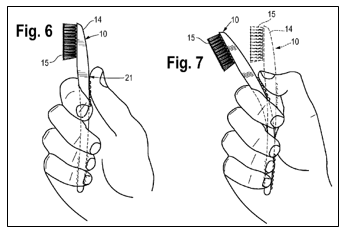

Claim 1 of the 285 patent is representative and is reproduced below:

A toothbrush, comprising:

an elongated body being flexible throughout the elongated body and comprising a first material and having a head portion and a handle portion;

a head comprising a second material, wherein the head is disposed in and molded to the head portion of the elongated body; and

a plurality of bristles extending from the head forming a bristle brush,

wherein the first material is less rigid than the second material.

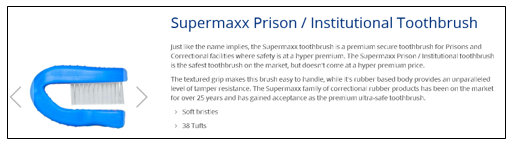

Maxill, Inc. makes “Supermaxx Prison/Institutional” toothbrushes that have a rubber-based, flexible body.

Loops and Maxill have for years been embroiled in patent infringement litigation, both in the U.S. and abroad, over flexible toothbrushes. This appeal arose out of a district court declaratory judgment action initiated by Maxill, who sought declaratory judgment of non-infringement and invalidity of the 285 patent.

During the district court proceeding, Loops moved for summary judgment of infringement. In their opposition, Maxill argued that whereas the “flexible throughout” limitation in the 285 patent claims required that the body of the toothbrush be flexible from one end to the other, only the handle portion of the body of the Supermaxx toothbrush was flexible. The head portion of the toothbrush body, including the head, did not bend.

The district court agreed with Maxill, finding that Maxill’s Supermaxx toothbrush did not satisfy the “flexible throughout” limitation because the head portion of the toothbrush body, combined with the head, was rigid and unbendable. The district court then took the rare step of sua sponte granting Maxill summary judgment of non-infringement.

Loops appealed.

The main issue on appeal is the proper construction of the “flexible throughout” limitation. The question, however, is not simply whether the claim limitation requires that the body be flexible from one end to the other, but rather, whether the body must be flexible from one end to the other once assembled with the head.

As noted above, claim 1 of the 285 patent requires “an elongated body being flexible throughout the elongated body…and having a head portion and a handle portion”, and “a head…is disposed in and molded to the head portion of the elongated body”.

Does the “flexible throughout” limitation apply to the elongated body when it is combined with the head (i.e., post-assembly)? In that case, the district court was correct and Maxill’s Supermaxx toothbrush would not infringe the 285 patent.

Or does the “flexible throughout” limitation apply to the elongated body alone (i.e., pre-assembly)? In that case, the district court was wrong and Maxill’s Supermaxx toothbrush would be potentially infringing.

The Federal Circuit disagrees with the district court, determining that the “flexible throughout” limitation pertains to the elongated body alone and does not extend to the head even when the head is molded to the elongated body.

The Federal Circuit first looks at the claims, finding that the claims do not describe the head “as being a part of the elongated body; rather, the head…is identified in the claim as a separate element from the elongated body”.

Even though the claims require that the head be “disposed in and molded to” the elongated body, this recitation “does not meant that the head loses its identity as a separately identifiable component of the claimed toothbrush and somehow merges into becoming a part of the elongated body”,

The Federal Circuit then looks at the specification, finding that the specification consistently describes the head and elongated body as separate components.

Finally, the Federal Circuit finds that the prosecution history does not contain any “disclaimer requiring that the head be considered in evaluating the flexibility of the elongated body”.

The Federal Circuit is also bothered by the district court’s sua sponte summary judgment of non-infringement. This sua sponte action, says the Federal Circuit, deprived Loop of a full and fair opportunity to respond to Maxill’s non-infringement positions.

This case is interesting because the patentee seems to have accomplished a lot with (intentionally?) imprecise claim drafting. While the specification describes that the elongated body, as a standalone component, is fully flexible, there is no description that once combined with the head, the head portion of the elongated body remains flexible. But if the claims are construed the way the Federal Circuit has, written description or enablement is not an issue. And during prosecution, the patentee was able to distinguish over prior art teaching partially flexible toothbrush handles by arguing that the claimed elongated body was flexible throughout, but also distinguish over prior art disclosing toothbrushes with fully flexible handles and removable heads by arguing that the “permanent disposition of the head in the head portion is paramount in providing a fully flexible toothbrush while also providing the rigidity required in the head to effectively brush teeth”.

Takeaway

- Claim elements tend to be construed as identifiably separate components in the absence of claim language or descriptions in the specification indicating that the components are formed as a unitary whole. Take care when amending claims to add features that may exist only when the components are assembled or disassembled.

A Pencil Copying A Pencil Copying A Pencil: Patented Design Intentionally Resembling A No. 2 Pencil Not Infringed by Copycat

| June 3, 2020

Lanard Toys Limited v. Dolgencorp LLC

May 14, 2020

Before Lourie, Mayer, and Wallach (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

Where a design patent claims an ornamental design that intentionally resembles a common object having a well-known appearance and well-known functional features, such as a No. 2 pencil, the smaller differences in the design take on greater significance in determining not only the scope, but also infringement, of the design patent. The theory of infringement of a design patent cannot be based solely on design elements that are already known in the prior art or that are functional.

Details

Lanard Toys Limited (“Lanard”) is perhaps better known for its long-lasting, massively produced lines of The Corps! action figures, which were marketed as the more affordable alternatives to the G.I. Joe action figures.

But (unfortunately) these action figures are not the toy at issue in Lanard’s dispute with Ja-Ru, Inc. (“Ja-Ru”), a fellow toymaker; Dolgencorp LLC, a distributor; and Toy “R” Us-Delaware, Inc., a toy retailer.

Rather, the toy at issue is a chalk holder in the shape of an oversized, No. 2 pencil that can hold pieces of colored chalk for children to draw on sidewalks.

From 2011 to 2014, Dolgencorp distributed, and Toys “R” Us sold, Lanard’s “chalk pencils”. Then, in 2013, Ja-Ru began marketing its own chalk holder. Ja-Ru admitted during litigation that they had used Lanard’s chalk pencil as a reference for designing and developing their product. Beginning with the 2014 toy season, Dolgencorp and Toys “R” Us stopped ordering Lanard’s chalk pencils, and began offering Ja-Ru’s product instead.

Lanard owns U.S. Design Patent No. D671,167 (“D167 patent”), titled “chalk holder” and claims the “ornamental design for a chalk holder”.

Reproduced below (from left to right) are representative Figure 1 from the D167 patent, Lanard’s chalk pencil, and Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil:

Lanard sued Ja-Ru, Dolgencorp, and Toys “R” Us for design patent infringement.[1] When the parties cross-moved for summary judgment on the question of infringement, the district court sided with Ja-Ru, granting summary judgment that Ja-Ru’s product did not infringe Lanard’s D167 patent. Lanard appealed.

On appeal, Lanard challenges the district court’s claim construction, asserting that the district court erroneously eliminated design elements from the scope of the D167 patent. Second, Lanard challenged the district court’s infringement analysis as failing to comport with the “ordinary observer” test.

The Federal Circuit rejected both of Lanard’s challenges, and adopted the district court’s determinations basically without modification on every one of Lanard’s contentions

Claim construction

Design patents “typically are claimed as shown in drawings”.[2] Functional characteristics in a design may limit the scope of protection, as “the scope of the claim must be construed in order to identify the non-functional aspects of the design as shown in the patent.”[3]

Further, the construction of a design patent involves identifying “various features of the claimed design as they relate to the accused design and the prior art.”[4] Prior art may be especially important in revealing the functionally necessary design elements, where “[e]very piece of prior art identified by the parties that incorporates similar elements configures them in the exact same way.”[5] Those elements represent the “broader general design concepts” that are excluded from design patent protection.

Here, Lanard argues that the district court improperly eliminated elements of the claimed designed based on functionality or lack of novelty.

The Federal Circuit, to the contrary, finds no fault with the district court’s claim construction, going so far as to note approvingly that the district court “followed our claim construction directives to a tee.”

The Federal Circuit appreciates that the district court meticulously factored out the functional “general design concepts” in Lanard’s claimed design:

- the conical tapered piece for holding the chalk in place during use;

- the wide and elongated body for storing the chalk and for the user to grasp;

- the ferrule attaching the eraser to the body of the chalk holder; and

- the eraser.

The Federal Circuit agrees with the district court that the elements listed above are common to No. 2 pencils, and are indeed utilitarian concepts that are found in every piece of writing utensil-related prior art cited during prosecution.

The Federal Circuit also agrees with the district court’s identification of the protectable ornamental elements in the D167 patent:

- the size and angle of taper of the conical piece;

- the hexagonal shape of the body

- the specific grooves on the ferrule;

- the columnar shape of the eraser; and

- the precise proportions of the various design elements relative to each other.

Before the district court, Lanard argued that the prior art does not combine the elements of a pencil with a chalk holder. The district court found Lanard’s argument to be unavailing, and the Federal Circuit agrees wholeheartedly.

Lanard’s argument is analogous to arguing that the intended use of an invention in a utility patent distinguishes the invention over the prior art. Such an argument can be difficult to make for a utility patent, and even more so in the context of a design patent. And the district court concluded as much.

Lanard’s patented design, as shown in the drawings, deliberately mimics a No. 2 pencil. The drawings do not differentiate between a toy and an actual pencil. Further, Lanard’s argument contains an implicit admission that elements of the D167 patent were taken from well-known designs for pencils. If, as Lanard asserted, the intended function was the only difference between Lanard’s design and the prior art, then Lanard’s design would not be patentable. The district court based its infringement analysis on the assumption that the D167 patent was valid.

On a side note, I believe this case is distinguishable from the Federal Circuit’s recent decision in Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2019) (case reviewed presented by Sung-Hoon Kim). In Curver,the Federal Circuit limited the scope of the claimed design (i.e., a pattern for a surface ornamentation) to the article of manufacture recited in the claim (i.e., a chair). However, the Federal Circuitalso noted that they were confronted with an atypical situation in Curver, because in most design patents, the drawings themselves depict a particular article of manufacture. Because the drawings in D167 patent identify the article of manufacture, Curver unlikely would have helped Lanard’s claim construction argument.

Infringement

The “ordinary observer” test for design patent infringement requires a comparison of the similarities in overall designs, not similarities of ornamental features in isolation. Under the “ordinary observer” test, courts may discount functional elements, but the analysis must focus on “how [the ornamental features] impact the overall design.”[6]

As in claim construction, the infringement analysis cannot ignore the prior art:

[T]he ordinary observer is deemed to view the differences between the patented design and the accused product in the context of the prior art. When the differences between the claimed and accused design are viewed in light of the prior art, the attention of the hypothetical ordinary observer will be drawn to those aspects of the claimed design that different from the prior art. And when the claimed design is close to the prior art designs, small differences between the accused design and the claimed design are likely to be important to the eye of the hypothetical ordinary observer.[7]

In this case, the district court determined that as compared to Lanard’s claimed design, Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil had:

- a more rotund and more stunted body;

- a shorter, more gradually sloping, and ridged conical piece; and

- a ferrule with a different pattern.

The district court concluded that, based on those distinctions, an ordinary observer would not consider Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil to have the same design as claimed in the D167 patent.

On appeal, Lanard argues that the district court’s infringement analysis compared the designs on an element-by-element basis, rather than comparing their overall appearances. Lanard also argues that the district court focused on features that distinguished the claimed design over the prior art, so that the district court was in effect reverting to the now-defunct “point of novelty” test. The “point of novelty” test would have asked whether Ja-Ru had stolen the novel aspects of Lanard’s patented design that distinguished it from the prior art.

The Federal Circuit rejects both of Lanard’s arguments.

As the district court noted, and which the Federal Circuit agrees, the problem for Lanard is that the asserted design similarities between the claimed design and Ja-Ru’s product stem from aspects of the design that are either functional or well-established in the prior art.

Lanard wants the district court and the Federal Circuit to find infringement on the basis that Ja-Ru’s product and the claimed design share the overall appearance of a No. 2 pencil. But this is precisely the argument that Lanard should not make.

Any aspect of Lanard’s claimed design that relates to the function of a No. 2 pencil or the conventional, well-known appearance of a No. 2 pencil are not patentable, and as such, are excluded from the scope of the design patent during claim construction and cannot be the basis for establishing infringement.

Lanard’s argument is made weaker by the ubiquity of No. 2 pencils. The Federal Circuit agrees with the district court’s finding that, because of the crowdedness of the field of pencils or writing utensils in general, the ornamental features in Lanard’s claimed design which are not dictated by function and which are not in the prior art take on greater significance. Far from being inconsequential and minor, those ornamental distinctions would dominate an ordinary observer’s attention when evaluating the overall appearances of Ja-Ru’s product and Lanard’s claimed design. The Federal Circuit agrees with the district court that those ornamental distinctions are sufficient to preclude a finding of infringement.

What troubles the district court and the Federal Circuit especially is what they perceive to be an attempt by Lanard to monopolize the basic design concepts underlying a pencil. They believe that Lanard’s arguments, if accepted, would “exclude any chalk holder in the shape of a pencil and thus extend the scope of the D167 patent far beyond the statutorily protected ‘new, original and ornamental design’.”

Takeaway

- In a crowded art, the devil and God are in the detail. The nuances in a design can take on greater significance where the article of manufacture embodying the design (or the article of manufacture that the design is intended to resemble) has a well-known appearance.

- While the scope of a design patent is limited to the drawings, courts during litigation have often relied on “verbal descriptions” of the claimed design to construe the claim. Be strategic about those verbal descriptions. For example, a quick review of the prior art cited during prosecution suggests that Lanard’s claimed design and the design of Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil may be closer to each other than to the cited prior art—in that case, Lanard might have offered a verbal description of the D167 patent drawings that downplayed the differences between those drawings and Ja-Ru’s chalk pencil, and still distinguished over the prior art.

- Drawings in a design patent application should reflect the intended function of the claimed design. A potential weakness in Lanard’s design patent may be that the drawings look too much like the article of manufacture (i.e., No. 2 pencil) that the claimed design is intended to resemble. If Lanard’s intention was to claim an oversized, toyish rendition of the No. 2 pencil, perhaps the patent drawings could have better emphasized the exaggerated proportions of the various chalk holder parts relative to each other.

[1] Lanard also alleged copyright and trade dress infringement, but this review will focus only on the design patent issues.

[2] Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665, 679 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

[3] Sport Dimension, Inc. v. Coleman Co., 820 F.3d 1316, 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

[4] Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 680.

[5] Richardson v. Stanley Works, Inc., 610 F.Supp.2d 1046, 1049 (D. Ariz. 2009), aff’d 597 F.3d 1288 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

[6] Richardson, 597 F.3d at 1295.

[7] Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 671.

There is a Standing to Defend Your Expired Patent Even If an Infringement Suit Has Been Settled

| July 8, 2019

Sony Corp. v. Iancu

Summary:

The CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision, in which the PTAB found that the limitation “reproducing means” is not computer-implemented and does not require an algorithm because this limitation should have been construed as computer-implemented and that the corresponding structure is a synthesizer and controller that performs the algorithm described in the specification. In addition, the CAFC found that there is a standing to appeal to defend an expired patent because the CAFC’s decision would have a consequence on any infringement that took place during the life of the patent.

Details:

Sony is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 6,097,676 (“the ’676 patent”) and appeals the PTAB’s decision in IPR, in which the PTAB found claims 5 and 8 of the ’676 patent unpatentable as obvious.

The ’676 patent:

The ’676 patent is directed to an information recording medium that can store audio data having multiple channels and a reproducing device that can select which channel to play based on a default code or value stored in a memory. This reproducing device has (1) storing means for storing the audio information, (2) reading means for reading codes associated with the audio information, and (3) reproducing means for reproducing the audio information based on the default code or value.

Claim 5 of the ’676 patent recites:

5. An information reproducing device for reproducing an information recording medium in which audio data of plural channels are multiplexedly recorded, the information reproducing device comprising:

storing means for storing a default value for designating one of the plural channels to be reproduced; and

reproducing means for reproducing the audio data of the channel designated by the default value stored in the storing means; and

wherein a plurality of voice data, each voice data having similar contents translated into different languages are multiplexedly recorded as audio data of plural channels; and a default value for designating the voice data corresponding to one of the different languages is stored in the storing means.

Claim 8 recites the same features as claim 5 with some additional features.

The PTAB:

The PTAB instituted IPR as to claims 5 and 8 of the ’676 patent. The issue during IPR was whether the “reproducing means” was computer-implemented and required an algorithm.

On September, 2017, the PTAB issued a final decision, where the claims were found to be unpatentable as obvious over the Yoshio reference. The PTAB construed the “reproducing means” has a means-plus-function limitation, and found that its corresponding structure is a controller and a synthesizer, or the equivalents. Furthermore, the PTAB found that this limitation is not computer-implemented and does not require an algorithm because a controller and a synthesizer are hardware elements.

The CAFC:

The CAFC agreed with Sony’s argument that the “reproducing means” requires an algorithm to carry out the claimed function.

The CAFC held that:

“In cases involving a computer-implemented invention in which the inventor has invoked means-plus-function claiming, this court has consistently required that the structure disclosed in the specification be more than simply a general purpose computer or microprocessor.” Aristocrat Techs. Austl. Pty Ltd. v. Int’l Game Tech., 521 F.3d 1328, 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2008). For means-plus-function claims “in which the disclosed structure is a computer, or microprocessor, programmed to carry out an algorithm,” we have held that “the disclosed structure is not the general purpose computer, but rather the special purpose computer programmed to perform the disclosed algorithm.” WMS Gaming, Inc. v. Int’l Game Tech., 184 F.3d 1339, 1349 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

The specification of the ’676 patent discloses that “[i]n reproducing such a recording medium by using the reproducing device of the present invention, the processing as shown in FIG. 16 is executed.” In fact, Fig. 16 discloses an algorithm in the form of a flowchart.

Therefore, the CAFC held that the “reproducing means” of claims 5 and 8 of the ’676 patent should be construed as computer-implemented and that the corresponding structure is a synthesizer and controller that performs the algorithm described in the specification.

Accordingly, the CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision and remand for further consideration of whether the Yoshio reference discloses a synthesizer and controller that performs the algorithm described in the specification, or equivalent, and whether the claims would have been obvious over the Yoshio reference.

Standing to Appeal:

The ’676 patent was expired in August 2017. Petitioners have elected not to participate in the appeal before the CAFC. The parties have settled the district court infringement suit involving this patent.

Is there a standing to appeal?

Majority: YES because

- The parties to this appeal remain adverse and none has suggested the lack of an Article III case or controversy.

- The PTO argues that the PTAB’s decision should be affirmed.

- Sony argues that the PTAB’s decision should be reversed and the claims should be patentable.

- The CAFC’s decision would have a consequence on any infringement that took place during the life of the ’676 patent (past damages subject to the 6-year limitation and the owner of an expired patent can license the rights or transfer title to an expired patent).

Dissenting: NO because

- No private and public interest (patent expired, petitioner declined to defend its victory, and infringement suit has been settled).

- No hint or possibility of present or future case or controversy by both parties and the PTO.

Takeaway:

- Even if the patent has expired, the patentee has a standing to appeal before the CAFC to dispute the PTAB’s final decision.

- An algorithm described in the specification for means-plus-function language helped the patentee with a narrow claim construction.

Tags: 112(f) > case or controversy > expired patent > hardware > infringement > means-plus-function > software > standing to appeal

A comparison of an accused product to a commercial product that meets all the claim limitations for finding infringement of the claim

| April 29, 2019

TEK Global S.R.L. v. Sealant Systems International Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2019) (Prost, C.J.) (Case No. 17-2507)

March 29, 2019

Prost, Chief Judge, Dyk and Wallach, Circuit Judges. Court opinion by Chief Judge Prost.

Summary

In a precedential opinion, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s claim construction in a specific context that an asserted claim including “container connecting conduit” was not subject to 35 U.S.C 112, ¶ 6 (112(f)) because the term “conduit” recites sufficiently definite structure to avoid classification as a nonce term. The Federal Circuit also affirmed the district court’s overruling of the accused infringer’s objections to certain alleged product-to-product comparisons in the patentee’s closing argument with general guidance that, despite the maxim that to infringe a patent claim, an accused product must meet all the limitations of the claim, a comparison of the accused product to a commercial product that meets all the claim limitations may support a finding of infringement of the claim.

Details

I. background

1. Patent in Dispute

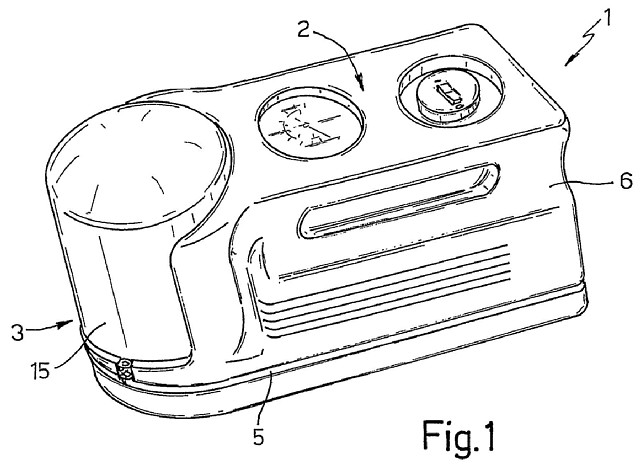

TEK Corporation and TEK Global, S.R.L. (collectively, “TEK”) owns U.S. Patent No. 7,789,110 (“’110 patent”), directed to an emergency kit for repairing vehicle tires deflated by puncture.

In a lawsuit by TEK against Sealant Systems International and ITW Global Tire Repair (collectively, “SSI”) at the United States District Court for the Northern District of California (“district court”), claim 26 is the only asserted independent claim:

26. A kit for inflating and repairing inflatable articles; the kit comprising a compressor assembly, a container of sealing liquid, and conduits connecting the container to the compressor assembly and to an inflatable article for repair or inflation, said kit further comprising an outer casing housing said compressor assembly and defining a seat for the container of sealing liquid, said container being housed removably in said seat, and additionally comprising a container connecting conduit connecting said container to said compressor assembly, so that the container, when housed in said seat, is maintained functionally connected to said compressor assembly, said kit further comprising an additional hose cooperating with said inflatable article; and a three-way valve input connected to said compressor assembly, and output connected to said container and to said additional hose to direct a stream of compressed air selectively to said container or to said additional hose.

2. Preceding Proceedings

In claim construction proceedings, SSI argued that “conduits connecting the container” and “container connecting conduit” in claim 26 are subject to 35 U.S.C. 112, ¶ 6, and that the claim requires a fast-fit coupling, which the accused product lacks.

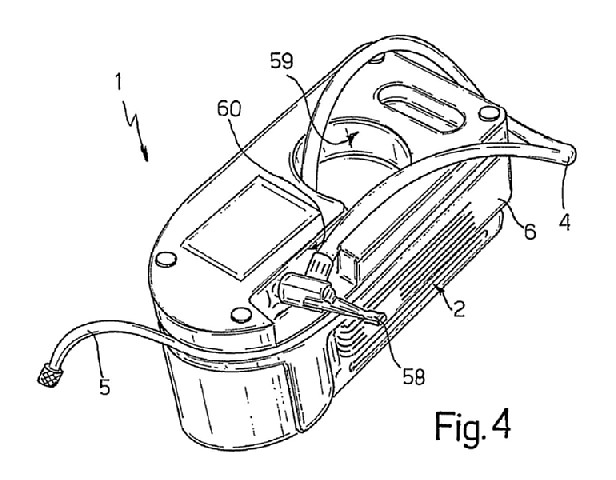

FIG. 1, showing a “view in perspective of a repair kit [1] comprising a container [3] of sealing liquid [and a compressor assembly 2],” is reproduced below

FIG. 4, showing a “underside view in perspective [o]f the FIG. 1 kit [1] partly disassembled,” and a portion of the specification of ’110 patent, relevant to the “fast-fit coupling” are reproduced below:

“Conveniently, hose 4 [i]s fitted on its free end with a fast-fit, e.g. lever-operated, coupling 58.” ’110 patent col. 4 ll. 7–9.

The magistrate judge rejected SSI’s contention, and entered an order respectively construing these terms (“conduits connecting the container” and “container connecting conduit”) as “hoses and associated fittings connecting the container to the compressor assembly and to an inflatable article for repair or inflation” and “a hose and associated fittings for connecting the container to the compressor assembly.”

Following the claim construction, SSI moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that claim 26 was obvious over U.S. Patent Application No. 2003/0056851 (“Eriksen”) in view of Japanese Patent No. 2004-338158 (“Bridgestone”). The district court granted SSI’s motion with determinations that the term “additional hose cooperating with said inflatable article” did not require a direct connection between the additional hose and the inflatable article, and that Bridgestone discloses an air tube (54) that works together with a tire, even though it is not directly connected to the tire, and that air tube (54) therefore represents the element of an additional hose (83) cooperating with the tire. TEK appealed the district court’s order to the Federal Circuit.

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s construction of the “cooperating with” limitation and its subsequent invalidity determination, and remanded the case back to the district court, because SSI “has not had an opportunity to make a case for invalidity in light of this court’s claim construction.”

On remand, SSI again moved for summary judgment of invalidity, contending that “it would have been obvious . . . to modify Bridgestone to eliminate the second three-way valve (60) and joint hose (66), resulting in a conventional tire repair kit meeting the limitations of the claims of the 110 Patent.” The magistrate judge denied SSI’s motion, noting that “the Federal Circuit has already considered and rejected obviousness in light of the combination of Eriksen and Bridgestone.”

Following a four-day trial, the jury found the asserted claims including claim 26 of the ’110 patent infringed and not invalid. The jury awarded $2,525,482 in lost profits and $255,388 in the form of a reasonable royalty for infringing sales for which TEK did not prove its entitlement to lost profits.

SSI then moved for a new trial on damages (or remittitur) and for JMOL on damages, invalidity, and noninfringement. The district court denied SSI’s motions for a new trial and for JMOL on invalidity and noninfringement. As to SSI’s motion for JMOL on damages, the district court denied the motion with respect to lost profits and granted it with respect to reasonable royalty. The district court also granted TEK’s motion for a permanent injunction. SSI appealed to the Federal Circuit.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit vacated the district court’s final judgment as to validity and reversed its denial of SSI’s motion for partial new trial on validity. In the interest of judicial economy, the Federal Circuit also reached the remaining issues on appeal including claim construction and infringement, and affirmed on those issues in the event the ’110 patent is found not invalid following the new trial.

This article focuses on the issues of the claim construction and infringement.

1. Claim Construction

(a) Fast-fit coupling

Review the district court’s claim construction de novo, and any underlying factual findings based on extrinsic evidence for clear error, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s claim construction, concluding that the intrinsic and extrinsic evidence in this case establishes that the term “conduit” recites sufficiently definite structure to avoid classification as a nonce term and agreed with the district court that SSI did not meet its burden to overcome the presumption against applying 35 U.S.C. 112, ¶ 6.

First, the Federal Circuit noted that SSI did not dispute that the elements connected via the conduits—i.e., the container, the compressor assembly, and the inflatable article (e.g., a tire)—each comprise definite structure, and that SSI did not dispute that the “hose” disclosed in the ’110 patent is structural.

Second, the Federal Circuit concluded that the ’110 patent (intrinsic evidence) clearly contemplates a conduit having physical structure. Indeed, the disclosed conduits serve to physically connect a container of sealing liquid to a compressor and to connect the compressor to tires such that “[t]he liquid is fed into the [tire] for repair by means of compressed air, e.g., by means of a compressor.” ’110 patent col. 1 ll. 13–14. Note that the cited portion in the parentheses is described in the “BACKGROUND ART” section of the specification without reference to any drawing in the patent.

Third, citing the applicant’s statement when adding new claim 26 to its patent application, “[n]ew claim 26 is similar to claim 10 but defines the connections in structural terms rather than ‘means for’ language,” the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s determination that the prosecution history establishes that the applicant intended for the term “conduit” to avoid the application of 35 U.S.C. 112, ¶ 6, with note that “[t]he subjective intent of the inventor when he used a particular term is of little or no probative weight in determining the scope of a claim,” but that is not necessarily true when the intent is “documented in the prosecution history.” Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., 52 F.3d 967, 985 (Fed. Cir. 1995) (en banc) (emphasis added).

Finally, the Federal Circuit indicated that extrinsic evidence also supports the conclusion. For example, dictionary definitions at or around the time of the invention confirm that the noun “conduit” denoted structure with “a generally understood meaning in the mechanical arts.” Greenberg v. Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., 91 F.3d 1580, 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (explaining that the dictionary definition of “detent” shows that a person skilled in the art would understand the term to connote structure); Webster’s Third New International Dictionary 474 (1993) (defining “conduit” as “a natural or artificial channel through which water or other fluid passes or is conveyed: aqueduct, pipe”); The New Oxford American Dictionary 358 (2001) (defining “conduit” as “a channel for conveying water or other fluid”).

(b) Outer casing connected to compressor

SSI also argues that because claim 26 requires that the “seat is part of the outer casing[,] . . . the outer casing connects the container to the compressor.”

Regarding the issue, the Federal Circuit indicated that its inquiry is limited to whether substantial evidence supports the jury’s infringement verdict under the issued claim construction, and did not reach whether the accused product infringes the asserted claims under SSI’s posited constructions because the district court expressly rejected SSI’s interpretation when determining that the term should have its plain and ordinary meaning, and because SSI did not appeal the district court’s claim construction order rejecting its interpretation of the plain and ordinary meaning.

2. Infringement (Product-to-Product Comparison)

SSI argued that the district court legally erred by allowing TEK, over SSI’s objections, to compare the accused product to TEK’s commercial embodiment during its closing argument.

While the Federal Circuit agreed with SSI’s assertion that to infringe, the accused product must meet all the limitations of the claim, the Court noted, “when a commercial product meets all the claim limitations, then a comparison [of the accused product] to that [commercial] product may support a finding of infringement.”

Regarding this case, the Federal Circuit stated that it cannot say that the district court abused its discretion by allowing the jury to hear the indirect product-to-product comparison, given that SSI’s own expert, Dr. King, acknowledged that he understood the TEK device to be an “embodying device” and to “practice[] the ’110 Patent,” and that certain statements made by SSI’s former executive, TEK’s counsel, and the inventor also suggest that TEK’s device is the commercial embodiment of the ’110 patent.

The Federal Circuit affirmed that the district court overruled SSI’s objections to certain alleged product-to-product comparisons in TEK’s closing argument because it determined that “SSI and its expert invited a product-to-product comparison by identifying TEK’s product as an embodiment of the invention, then drawing a contrast (albeit an unconvincing one) with SSI’s product.”

The Federal Circuit also affirmed that the district court, in its discretion, determined that the indirect comparison between TEK’s product and SSI’s product, in the context that it occurred, was not cause for a new trial. For the support of the affirmance, the Federal Circuit referred to the district court’s instruction directing the jury not to perform a product-to-product comparison to decide the issue of infringement (“You’ve heard evidence about both TEK’s product and SSI’s product. However, in deciding the issue of infringement, you may not compare SSI’s Accused Product to TEK’s product. Rather, you must compare SSI’s Accused Product to the claims of the ’110 Patent when making your decision regarding patent infringement.”). In the Federal Circuit’s view, the district court’s cautionary instructions are sufficient to mitigate any potential jury confusion or substantial prejudice to SSI due to the apparent product-to-product comparison.

In light of the above considerations, the Federal Circuit concluded that the district court did not abuse its discretion, and thus declined to reverse its denial of SSI’s motion for a new trial on infringement.

Takeaway

• The term “conduit” is now a member of examples of structural terms that have been found not to invoke 35 U.S.C. 112(f) or pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 112, paragraph 6. See MPEP 2181 [R-08.2017].

• Despite the maxim that to infringe a patent claim, an accused product must meet all the limitations of the claim, a comparison of the accused product to a commercial product that meets all the claim limitations could support a finding of infringement of the claim.

It all begins with Claim Construction

| February 15, 2019

Duncan Parking v. IPS Group

January 31, 2019

Before Lourie, Dyk, and Taranto. Decision by Lourie.

Summary:

The trial judge construed the claims and subsequently granted summary judgment in favor of Defendant Duncan that the accused parking meters do not infringe U.S. Patent No. 8,595,054 owned by Plaintiff IPS. On appeal the CAFC determined that the trial judge had misconstrued the claims, vacated the summary judgment of non-infringement, and remanded the case to the trial judge for reconsideration of the infringement issue in light of the proper claim construction.

Details:

Claim 1 of the ‘054 patent recites:

- A parking meter device that is receivable within a housing base of a single space parking meter, the parking meter device including:

a timer;

a payment facilitating arrangement operable in cooperation with a non-cash payment medium for effecting payment of a monetary amount for a parking period;

a display configured to visually provide a balance remaining of the parking period;

a power management facility that supplies power to the timer, payment facilitating arrangement, and display;

a wireless communications subsystem configured to receive information relating to the non-cash payment medium in respect of the payment facilitating arrangement;

a keypad sensor that receives input comprising manipulation by the user;

a coin slot into which coins are inserted for delivery to the coin sensor and then to a coin receptacle; and

a lower portion and an upper portion;

wherein the keypad sensor operates the parking meter and determines parking time amount for purchase in accordance with the received input from the user;

wherein the display provides the amount of time purchased in response to the received input from the user;

wherein the upper portion of the parking meter device includes a solar panel that charges the power management facility;

wherein the lower portion of the parking meter device is configured to have a shape and dimensions such that the lower portion is receivable within the housing base of the single space parking meter; and

wherein the upper portion of the parking meter device is covered by a cover that is configured to accommodate the upper portion and that is engageable with the housing base of the single space parking meter such that the payment facilitating arrangement is accessible by the user for user manipulation effecting the payment of the monetary amount for the parking period when the lower portion of the parking meter device is received within the housing base and the upper portion is covered by the cover.

10 – parking meter device

34 – housing

36 – cover

41 – window

Duncan’s accused parking meter is shown below.

The trial judge court construed “receivable within” as “capable of being contained inside,” and applied this construction to require that the “entire lower portion” of the infringing product be “receivable within the housing base.” The trial judge granted summary judgment of non-infringement because it found that the keypad of the accused meter extends through an opening in the lower portion of the housing and, as a result, the lower portion of Duncan’s meter is not “receivable within” its housing base.

On appeal IPS argued that the trial judge had

- construed the claim term “receivable within,” in the claim limitation “a lower portion [of the parking meter device] . . . receivable within the housing base” too narrowly, requiring that the entire lower portion of the parking meter device be contained inside the parking meter housing;

- erroneously construed claim 1 to exclude a potential unclaimed “middle portion” of the device between the upper and lower portions; and

- excluded the preferred embodiment from the scope of claim.

On the latter point, IPS explained that the card slot and the coin slot (both parts of the device itself) cannot be part of the upper portion of the device because the upper portion must be covered by the cover panel. But they also cannot be a part of the lower portion of the device because they are not “receivable within” the housing base as per the district court’s claim construction. Instead, they are accessible through openings in the housing. Thus, either the coin slot and card slot comprise a “middle portion” not defined by the ‘054 claims or the ‘054 specification, or the trial judge’s construction of “receivable within” is too narrow.

DPT replied

- that the plain meaning of “within” is “inside,” and IPS choose not to modify the term with the words “generally” or “substantially”;

- that the trial judge’s claim construction does not actually exclude the preferred embodiment because the coin slot is still inside the housing base; while the coin slot of the preferred embodiment is accessible through an opening in the housing, it does not actually protrude through that opening; and

- that prosecution history estoppel bars IPS from asserting that claim 1 includes parking meter devices that are not entirely contained within a housing.

The CAFC touched on familiar issues, commenting on the trial judge’s approach to claim construction and then addressing the parties’ argument.

The Trial Judge’s Approach:

The trial judge construed the term “receivable within” as “capable of being contained inside,” but upon applying the claim construction in its infringement analysis added a requirement that the “entire” lower portion of the device must be contained within the housing, id. at 8, effectively altering the construction to “capable of being contained entirely inside.”

Dictionaries:

A reasonable meaning of the term “receivable within” in the context of the ’054 patent is “capable of being contained inside.” Receive, The New Oxford American Dictionary (2d ed. 2005) (defining “receive” as “to act as a receptacle for” and “receptacle” as “an object or space used to contain something”).

The suffix “-able” implies that the lower portion of the device is capable of being contained within the housing base. But this definition contains no limitation to “completely” or “entirely” contained, nor is there any evidence that persons of skill in the art would understand it to be so limited. Indeed, Duncan touted its accused meter because it “fits within” existing parking meter housings.

The ‘054 Specification:

The only use of the term “receivable” in the ‘054 specification does not imply any limitation to devices “entirely” contained by the housing (“The parking meter device in accordance with the invention may be receivable in a conventional single space parking meter housing, such as that supplied by Duncan Industries, POM or Mackay.”).

The trial judge’s claim construction did indeed exclude the preferred embodiment. The specification defines the coin slot as a part of the lower portion, even though it is not located “within” the housing base but is instead accessible through an opening. Whether the coin slot “protrudes” or not is beside the point; it is a part of the lower portion of the parking meter device but is not “capable of being contained [entirely] within” the housing base as required by the trial judge’s claim construction.

The ‘054 Prosecution History:

Duncan argued that a narrow construction was warranted by the ‘054 prosecution history because IPS had disavowed parking meter devices not fully enclosed by a housing in its response to an office action. Thus Duncan contended that by differentiating the prior art on the basis that it discloses an embodiment exposed to the elements, rather than one enclosed within a housing, IPS disavowed parking meter devices not entirely enclosed within a housing. IPS’s statements fall far short of a claim scope disavowal. IPS distinguished the cited prior art—an actual parking meter, not an insertable device—on the basis that it discloses a “self-contained unit,” as opposed to the claimed device, which is “a retro-fit upgrade to existing parking meters.”

Conclusion:

Because the CAFC agreed with IPS that the district court’s claim construction of “receivable within” was erroneous, it vacated the trial judge’s grant of summary judgment of non-infringement of the ’054 patent and remanded the case to the trial judge for further proceedings.

Takeaways:

The scope of claims is determined on the basis of how they are written, not as how they might have been written.

Dictionaries are almost always important.

A claim construction that excludes a preferred embodiment in the specification from the claim scope is usually wrong.

Disavowal of claim scope in a prosecution history is rare.

When the acts of one are attributable to the other.

| February 16, 2017

Eli Lilly and Company, v. Teva Parenteral Medicines, Inc., APP Pharmaceuticals LLC., Pliva Hrvatska D.O.O., Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., Barr Laborites, Inc.

January 12, 2017

Before Prost, Newman and Dyk. Opinion by Prost.

Summary:

The case centered on Eli Lilly’s patent directed to methods of administering a chemotherapy drug after pretreatment with two common vitamins. The drug was marketed under the brand name ALIMTA®. The Defendants had submitted ANDAs seeking approval of a generic version of ALIMTA®. The CAFC upheld the district counts findings, in favor of Eli Lilly’s patent, in full. The issues addressed were induced infringement, and invalidity issues of indefiniteness, obviousness and obvious-type double patenting.

Details:

Eli Lilly is the owner of U.S. Patent No., 7,772,209 (patent ‘209), directed to methods of administering the chemotherapy drug “pemetrexed’ after pretreatment with two common vitamins (folic acid and vitamin B12). The purpose of the dual vitamin pretreatments is to reduce the toxicity of the pemetrexed to the patients. The drug was marketed under the brand name ALIMTA®.

The Defendants notified Eli Lilly that they had submitted ANDAs seeking approval of a generic version of ALIMTA®. After the ‘209 patent issued, Defendants sent Eli Lilly notices that they had filed Paragraph IV certifications under 21 U.S.C. §355(j)(2)(A)(vii)(IV), declaring that the patent was invalid, unenforceable or would not be infringed. Eli Lilly subsequently brought a consolidated action against the Defendants for infringement, alleging that the generic drug would be administered with folic acid and vitamin B12 pretreatments.

Eli Lilly asserted a number of claims at trial, all of which required patient pretreatment by ‘administering’ or ‘administration of’ folic acid, and a number of dependent claims which defined dosage restrictions.

The parties agreed for the purpose of appeal that no single actor performs all steps, rather they are divided between patient and physician. Specifically, physicians administered vitamin B12 and pemetrexed, while the patient folic acid.

Initially, in June 2013, Defendants conditionally conceded induced infringement under the then-current law set forth in Akamai II (Akamai II held that “induced infringement can be found even if there is no single party who would be liable for direct infringement”). At the time, Akamai was subject of a petition to the Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari. The parties’ stipulation included a provision reserving Defendants right to litigate infringement if the Supreme Court reversed or vacated Akamai II. While an appeal on invalidity was pending (district court had held the claims were not invalid), the Supreme Court reversed Akamai II, holding the liability for inducement cannot be found without direct infringement. In view of this, the parties in this case filed a joint motion to remand the matter to the district court for the limited propose of litigating infringement. CAFC granted the motion. The district court held a second bench trial and concluded that Defendants would induce infringement of the ‘209 patent. The court had applied the intervening Akamai V decision, which had broadened the circumstances in which others’ acts may be attributed to a single actor to support direct infringement liability.

Defendants timely appealed. The CAFC upheld the district courts findings, addressing each issue in turn.

(I) “Whoever actively induces infringement of a patent shall be liable as an infringer.” Importantly, liability for induced infringement “must be predicated on direct infringement.” (Akamai III). The patentee must also show that the alleged infringer “knew or should have known his actions would induce actual infringements.” A patentee seeking relief under §271(e)(2) bears the burden of prove.

The district court relied in part on the Defendants’ proposed product labeling as evidence of infringement. The labeling consisted of two documents: the Physician Prescribing Information and the Patient Information. Amongst other things, the information provides the following:

Instruct patients to initiate folic acid 400 [m]g to 1000 [m]g orally once daily beginning 7 days before the first dose of [pemetrexed]…

Instruct patients on the need for folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation to reduce treatment-related hematologic and gastrointestinal toxicity…

To lower your chances of side effects of [pemetrexed], you must also take folic acid and vitamin B12 prior to and during your treatment with [pemetrexed].

It is very important to take folic acid and vitamin B12 during your treatment with [pemetrexed] to lower your chances of harmful side effects. You must start taking 400-1000 micrograms of folic acid every day for at least 5 days out of the 7 days before your first dose of [pemetrexed].

The CAFC held that where, as here, no single actor performs all the steps of the method claim, direct infringement only occurs if “the acts of one are attributable to the other such that a single entity is responsible for the infringement.” Akamai V. In Akamai V, the CAFC held that directing or controlling other’s performance includes circumstances in which an actor (1) conditions participation in an activity or receipt of a benefit upon another’s performance of one or more steps of a patented method, and (2) establishes the manner or timing of that performance. The district court applied this two-point prong test to the subject case.

With respect to the first prong – the CAFC agreed with the district court’s findings. Specifically, the labeling information repeatedly instructs the patients to take folic acid and provides information about the dosage range and schedule. The labeling information explains that the folic acid is a “requirement for premedication” in order to “reduce the treatment-related hematologic and gastrointestinal toxicity” of pemetrexed. Eli Lilly’s expert testified that it is “the physician’s responsibility to initiate the supplementation of folic acid.” The patient information also informs patients that a physician may withhold pemetrexed treatment based on blood tests. Eli Lilly’s expert testified that a physician would withhold treatment if the patient had not taken their required dosage of folic acid to avoid toxicity.

The Defendants argued that the product labeling was mere guidance and insufficient to show conditioning. The Defendants also argued there is no evidence that physicians go further to “verify compliance” with their instructions. The CAFC replied that conditioning does not necessarily require double checking.

Next, the Defendants argued that an actor can only condition the performance of a step by imposing a legal obligation to do so. The CAFC rejected this argument, stating that infringement is not limited solely to contractual arrangements, and the like.

With respect to the second prong – the CAFC agreed with the district court’s findings. Specifically, the Physician Prescribing Information instructs physicians to tell patients to take folic acid at specific dosages and at a specific schedule. Moreover, the testimony of a Dr. Chabner was highlighted in part affirming that “it is the doctor” who “decided how much” the patient takes.

Defendants argued that patients are able to seek additional outside assistance regarding folic acid administration, but the CAFC held this was immaterial.

Thus, the two-point prong test of Akamai V was met. However, the mere existence of direct infringement by physicians is not sufficient to find liability for induced infringement. Eli Lilly carried this burden.

The district court held that the administration of folic acid before pemetrexed administration was ‘not merely a suggestion or recommendation, but a critical step,’ in light of the Defendants proposed labeling.

Defendants argued that Eli Lilly has not offered any evidence of what physicians do in general but only speculation about how they may act. They argued that physicians must go beyond labeling. The CAFC found this argument unavailing. For the purpose of inducement “it is irrelevant that some users may ignore the warnings in the proposed label,” if the label “encourage(s), recommend(s) or promote(s) infringement.” The product labeling included repeat instructions and warning regarding the importance of folic acid.

(II) Indefiniteness of “vitamin B12” – the Defendants argued in view of Nautilius that vitamin B12 is indefinite as the term is used in two different ways in the intrinsic record (vitamin B12 and Cyanocobalamin).

The district count accepted the testimony of Eli Lilly’s expert that one of ordinary skill in the art would understand in the context of the patent claims vitamin B12 to mean Cyanocobalamin. The CAFC saw no error in the districts court findings, holding that vitamin B12 has a plain meaning to one of skill in this particular art.

In addition, it was noted that claim 1 required administering a “methylmalonic acid lowering agent…” and claim 2 “vitamin B12.” Therefore, if vitamin B12 was to refer to a whole class of compounds it would be the same scope as claim 1. However, the doctrine of claim differentiation presumes that dependent claims are of narrower scope, and so reading the claims as to require ‘vitamin B12’ of claim 2 to be a specific compound within the scope of “methylmalonic acid lowering agent” avoids this problem.

The Defendants argued that if vitamin B12 means Cyanocobalamin, the given Markush group in claim 1 of the “methylmalonic acid lowering agent,” lists the same compound twice. The CAFC held that the mere fact that a compound may be embraced by more than one member of a Markush group recited in the claim does not necessarily render the scope unclear. The CAFC held the redundancy is support by the prosecution history (the Examiner had stated they were the same, in response the patentee removed Cyanocobalamin, but later put the term back into the claim).

(III) Obviousness – the CAFC agreed with the district counts finding that a skilled artisan would have concluded that vitamin B12 deficiency was not the problem in pemetrexed toxicity.

In brief, the Defendant had relied upon an Abstract published from an Eli Lilly scientist that showed homocysteine levels served as an indicator of either a folic acid or vitamin B12 deficiency and that such levels were elevated with increased pemetrexed toxicities. However, the levels of another marker methylmalonic acid (MMA), which more specifically is an indicator of just vitamin B12 deficiency, showed no correlation. The CAFC indicated this was sufficient for the claims not to be rendered obvious.

(V) Obviousness-type double patenting – the Defendants argued that the claims are not valid over an Eli Lilly’s earlier patent (US 5,271,974 – ‘974). The district court disagreed, and the CAFC upheld.

In brief, the ‘974 patent more broadly claimed a much greater amount of folic acid with an antifolate agent administrated to a mammal. The claims of the subject patent are much more specific with regards to the amount of folic acid and the administration of a specific antifolate agent to a patient. The CAFC held this was sufficient for the claims to be patentably distinct.

Comments:

Method claims drafted to encompass actions of a single entity are still preferable, in order to reduce burden of proving infringement. However, where no single entity performs all the steps, direct infringement can be found if the steps of the method claim are performed under the control or direction by a single entity.

Naturally, patent specification drafters should always endeavor to be careful in their use of claim terminology. Even so, where claim terms are have a specific meaning in their relevant arts, the courts tend to not apply those terms contrary to their common understanding, unless the applicant clearly intended to redefine the term.

Tags: ANDA > double patenting > Generics > indefiniteness > infringement > obviousness

In a design patent infringement case, 35 U.S.C. §289 authorizes the award of total profit from the article of manufacture bearing the patented design

| May 27, 2015

Apple Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. et al.

May 18, 2015

Before: Prost, O’Malley and Chen. Opinion by Prost.

Summary

The CAFC affirmed the jury’s verdict on the design patent infringements and the validity of utility patent claims, and the damages awarded for these infringements appealed by Samsung. However, CAFC reversed the jury’s findings that the asserted trade dresses are protectable. Regarding the design patent infringement issue, Samsung proposed that functional aspects of the design patents should be “ignored” in their entirety in a design patent infringement analysis, the CAFC disagreed. Moreover, the CAFC found that the district court did not err by allowing jury to award damages based on Samsung’s entire profits on its infringing smartphones.

サムスン社は、控訴審において、意匠特許の機能的部分は意匠特許侵害の分析において無視されるべきであると主張した。CAFCは、機能的部分の装飾的な特徴は意匠特許によりカバーされるため、意匠特許侵害の分析において機能的部分を無視すべきというサムスン社の主張には同意しなかった。また、サムスン社は、意匠特許侵害の損害賠償は、侵害商品の全体としての利益(entire profit)に基づいて計算されるべきでないと主張したものの、特許法第289条は、意匠特許侵害の損害賠償を侵害商品の全体としての利益(entire profit)に基づいて計算することを可能としているため、CAFCはこの主張にも同意しなかった。

Be Mindful that the Potential Reach of Claimed Components under the Doctrine of Equivalents Can Be Affected by Amendments to Claimed Sub-Components.

| October 9, 2014

EMD Millipore Corporation v. Allpure Technologies, Inc. (Precedential Opinion).

September 29, 2014

Panel: Prost, O’Malley and Hughes. Opinion by Prost.

Summary

EMD Millipore Corporation (Millipore) appeals the District of Massachusetts decision that the accused infringer, Allpure Technologies, Inc. (Allpure) does not infringe its U.S. Patent No. 6,032,543 entitled a Device for Introduction and/or Withdrawal of a Medium into/from a Container, either literally or under the doctrine of equivalents. The Federal Circuit affirmed that there was no literal infringement because the claims required a removable transfer member having a two part seal connected after removal, while the Allpure device had two parts of a seal separated after disassembly. In addition, the Federal Circuit held that Allpure did not infringe under the doctrine of equivalents due to prosecution history estoppel based on narrowing amendments limiting the transfer member to such a two part seal, along with a lack of any argument that the reasons for such amendments was not a substantial one related to patentability.

Tags: doctrine of equivalents > infringement > literal infringement > prosecution history estoppel

Divided Claim Construction Leads to Reversal of Jury Verdict Against Alleged Infringer

| April 17, 2013

Saffran v. Johnson & Johnson

April 4, 2013

Panel: Lourie, Moore, and O’Malley. Opinion by Lourie. Concurrence Opinions by Moore and O’Malley.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed a $482 million jury verdict against Cordis, a member of the Johnson & Johnson family. The reversal came as a result of the Federal Circuit’s significant narrowing of the district court’s construction of two key claim limitations. One claim term was narrowed because the Federal Circuit found that the patentee’s arguments made during prosecution of the asserted patent, for the purpose of distinguishing over cited prior art, amounted to prosecution disclaimer. Meanwhile, a structure identified in the specification by the patentee as the corresponding structure to a means-plus-function limitation was disregarded as such, because the specification failed to link the identified structure to the recited function with sufficient specificity.

Tags: claim construction > infringement > means-plus-function > prosecution argument > prosecution disclaimer > prosecution history estoppel