Claim Construction Should Be Well-Grounded in Both Intrinsic and Extrinsic Evidence

| January 15, 2024

ACTELION PHARMACEUTICALS LTD v. MYLAN PHARMACEUTICALS INC.

Decided: November 6, 2023

Before REYNA, STOLL, and STARK, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The Federal Circuit ruled that the patent claim term “a pH of 13 or higher” could not be interpreted solely based on the patent’s intrinsic evidence. The court remanded the case to the district court, instructing it to consider extrinsic evidence to determine the proper construction of this claim limitation.

Background

The case of Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. involves a dispute over patent infringement related to epoprostenol, a drug used for treating hypertension. Actelion Pharmaceuticals, the patent holder, owns two patents of the drug: U.S. Patent Nos. 8318802 and 8598227. These patents disclose a pharmaceutical breakthrough in stabilizing epoprostenol using a high pH solution, which is otherwise unstable and difficult to handle in medical applications.

Mylan Pharmaceuticals, aiming to enter the market with a generic version of epoprostenol, filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). In this process, Mylan certified under Paragraph IV that the patents held by Actelion were either invalid or would not be infringed by Mylan’s manufacture, use, or sale of the generic drug. In response, Actelion asserted these patents against Mylan, claiming infringement.

The key issue in the dispute revolves around the interpretation of the phrase “a pH of 13 or higher” in the patent claims. This particular claim is crucial because the stability of epoprostenol is significantly impacted by the pH level of its solution. Actelion’s patents suggest that the epoprostenol bulk solutions should preferably have a pH adjusted to about 12.5 to 13.5 to achieve the desired stability. However, in the claims, Actelion’s patents only set the limitation as “a pH 13 or higher” as shown in claim 11 of the ’802 patent, a representative of the asserted claims:

11. A lyophilisate formed from a bulk solution comprising:

(a) epoprostenol or a salt thereof;

(b) arginine;

(c) sodium hydroxide; and

(d) water,

wherein the bulk solution has a pH of 13 or higher, and wherein said lyophilisate is capable of being reconstituted for intravenous administration with an intravenous fluid.

The dispute centered on the interpretation of the pH value specified in the patent claims. Actelion contended that the claim should encompass pH values that effectively round up to 13, including values like 12.5. Conversely, Mylan argued for a narrower interpretation, asserting that the claim should only cover pH values strictly at 13 or higher, thus excluding anything below this threshold, such as 12.5.

This interpretation was critical in determining whether Mylan’s generic version of epoprostenol would infringe upon Actelion’s patents. The district court initially adopted Actelion’s interpretation, which led to a stipulated judgment of infringement against Mylan.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit’s analysis began with a de novo review of the district court’s decision. The central question was whether the district court’s adoption of Actelion’s interpretation, which included pH values that could round up to 13 (such as 12.5), was appropriate. This broader interpretation affected the scope of the patent and the potential infringement by Mylan’s generic version of the drug. In scientific and technical contexts, the practice of rounding pH levels, such as rounding 12.5 to 13, depends on the specific requirements of the situation and the level of precision needed. pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution, and even small changes can represent significant differences in acidity or basicity.

Mylan Pharmaceuticals argued for a narrower interpretation of the term. They insisted that “a pH of 13” sets a definitive lower limit, suggesting that any pH value below 13, even those marginally lower like 12.995, would not fall within the scope of the patent. Mylan suggested that if a margin of error was considered necessary for a pH of 13, it should be minimal, encompassing a range only from 12.995 to 13.004. This interpretation was grounded in the belief that precision was implicit in the claim term, as the absence of approximation language like “about” in the claim suggested an exact value.

In contrast, Actelion Pharmaceuticals argued for a broader interpretation. They argued that the term should include values that round up to 13, thus potentially including values such as 12.5. Actelion’s argument was based on the principle that a numerical value in a patent claim includes rounding, dictated by the inventor’s selection of significant figures, unless the intrinsic record explicitly indicates a different intention. Actelion maintained that rounding was a common practice in scientific measurements and that the absence of specific approximation language did not necessarily dictate a precise value.

One of the key findings of the Federal Circuit was the inadequacy of intrinsic evidence to resolve the dispute conclusively. Intrinsic evidence, which includes the original patent claim language, specification, and prosecution history, is generally the primary resource for interpreting patent claims. However, in this case, these sources did not clearly define the precision of the pH value in question. The specification stated that, “the pH of the bulk solution is preferably adjusted to about 12.5-13.5, most preferably 13.” This language suggested that while the inventor recognized a preferred range (about 12.5-13.5), they specifically highlighted a most preferred value (13). The Federal Circuit also noted that the specification uses both “13” and “13.0” and various degrees of precision for pH values generally throughout the specification. Moreover, the prosecution history shows that the Examiner drew a distinction between the stability of a composition with a pH of 13 and that of 12. However, such distinction does not clarify the narrower issue of whether a pH of 13 could encompass values that round to 13, in particular 12.5.

The specifications and prosecution history left ambiguous whether the term referred exclusively to a pH of 13.0 or could include values that round up to 13. Recognizing this ambiguity, the Federal Circuit emphasized the need for extrinsic evidence to properly interpret the term. This approach is aligned with the Supreme Court’s guidance in Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., which acknowledged the importance of considering such evidence in certain contexts of patent claim interpretation. The Federal Circuit decided to vacate the district court’s ruling and remand the case for further consideration of extrinsic evidence.

Takeaway

- Precise and specific wording in patent claims is crucial, especially in technical fields, as it defines the scope and protection of the invention.

- Although intrinsic evidence (claim language, specifications, and prosecution history) is primary in patent interpretation, it may not always be sufficient. In cases where intrinsic evidence is ambiguous or lacks clarity, extrinsic evidence such as expert testimonies, scientific literature, and other technical documents becomes crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the claim.

Insufficient Extrinsic Evidence and Prosecution Disclaimer Led to Claim Construction in Patentee’s Favor

| May 6, 2022

Decided: April 1, 2022

Newman, Reyna, and Stoll. Opinion by Reyna.

Summary

The CAFC found in favor of a patentee seeking broad interpretation of a claim term, where an expert testimony offered by an opponent in support of narrower claim scope was insufficient to overcome a clear record of the patent, and the prosecution history lacked “clear and unmistakable” statements to establish express disavowal of claim scope.

Details

This is an appeal from a district court action where Genuine Enabling Technology LLC (“Genuine”) sued Nintendo Co., Ltd. and Nintendo of America, Inc. (“Nintendo”) for infringing certain claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,219,730. The patent relates to user input devices, such as mouse and keyboard, and its representative claim 1 recites:

1. A user input apparatus operatively coupled to a computer via a communication means additionally receiving at least one input signal, comprising:

user input means for producing a user input stream;

input means for producing the at least one input signal;

converting means for receiving the at least one input signal and producing therefrom an input stream; and

encoding means for synchronizing the user input stream with the input stream and encoding the same into a combined data stream transferable by the communication means.

(Emphasis added.)

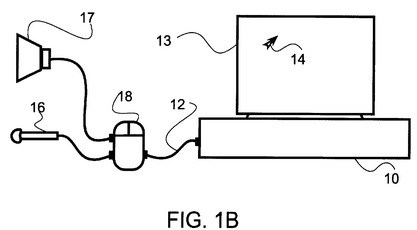

The inventive idea may be pictured as a “voice mouse.” As seen in Fig. 1B of the patent, the inventive apparatus or mouse 18, connected with a computer 10 via a communication link 12, serves the traditional function of allowing user to move an object 14 on the computer monitor 13 (i.e., “user input means for producing a user input stream”), while also capable of receiving a speech input from a microphone 16 (i.e., “input means for producing the at least one input signal”) and transmitting a speech output to a speaker 17.

At issue in the case is the construction of the term “input signal.”

During prosecution, the inventor distinguished his invention over U.S. Patent No. 5,990,866 (“Yollin”) cited in an office action, arguing that the “input signal” limitation was missing in the reference. Specifically, the inventor argued that various physiological sensors disclosed in Yollin, such as those detecting user’s muscle movement, heart rate, brain activity, blood pressure, skin temperature, etc., only produce “slow varying” signals as opposed to “signals containing audio or higher frequencies” to which his invention pertains. The inventor pointed out that the inventive apparatus would resolve a specific problem presented by the use of high frequency signals, which, unlike slow varying signals, tend to “collide” with other signals in producing a composite data stream. This “slow varying” vs. “audio or higher frequencies” distinction is repeatedly noted in the inventor’s argument.

The parties disputed the extent of prosecution disclaimer resulting from the inventor’s statements as to the term “input signal.” In the district court, Genuine proposed to construe the term as

“a signal having an audio or higher frequency,”

whereas Nintendo maintained that the proper scope should be narrower:

“A signal containing audio or higher frequencies. [The inventor] disclaimed signals that are 500 Hertz (Hz) or less. He also disclaimed signals that are generated from positional change information, user selection information, physiological response information, and other slow-varying information. Alternatively, indefinite.”

Nintendo argued that the inventor disclaimed the certain types of “slow-varying” signals taught by Yollin. While specific frequencies were not disclosed in Yollin, Nintendo relied on its expert testimony citing a reference purportedly showing that Yollin’s physiological sensors encompassed the range of “at least 500 Hz.”

Genuine contended that the disclaimed scope should be limited to “slow-varying signals below the audio frequency spectrum [of 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz],” in accordance with the inventor’s argument which only had distinguished the reference “slow-varying” signals from “fast-varying” signals.

The district court sided with Nintendo, finding non-infringement in its favor. In particular, the district court noted that “an applicant’s argument that a prior art reference is distinguishable on a particular ground can serve as a disclaimer of claim scope even if the applicant distinguishes the reference on other grounds as well.” Andersen Corp. v. Fiber Composites, LLC, 474 F.3d 1361, 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2007). That is, according to the district court, the fact that the inventor’s argument distinguished Yollin as lacking “audio or higher frequencies” did not negate the effect of the inventor’s statement also distinguishing Yollin’s range as “slow-varying” signals.

On appeal, the CAFC rejected the district court’s claim construction.

First, the CAFC noted that the role of extrinsic evidence in claim construction is limited, and cannot override intrinsic evidence where there is clear written record of the patent. And as one form of extrinsic evidence, “expert testimony may not be used to diverge significantly from the intrinsic record.” Here, the 500 Hz frequency threshold was not identified in the intrinsic record nor Yollin, and its only basis was Nintendo’s expert testimony which relied on another extrinsic reference that was not in the record. The extrinsic evidence conflicted with the prosecution history in which the examiner had accepted the inventor’s argument distinguishing Yollin without drawing a bright line between “slow-varying” and “audio or higher frequenc[y]” signals. As such, the CAFC found that the expert testimony cannot overcome the clarity of the intrinsic evidence.

Second, the CAFC noted that prosecution disclaimer requires that the patentee make a “clear and unmistakable” statement to disavow claim scope during prosecution. The fact that the inventor repeatedly distinguished the reference “slow-varying” signals from “audio or higher frequenc[y]” signals—the argument which successfully traversed the rejection—led the CAFC to decide that the “clear and unmistakable” disavowal was limited to “signals below the audio frequency spectrum.” Although the CAFC noted that the inventor’s statements “may implicate” certain frequency ranges such as 500 Hz or less, the intrinsic record was not unambiguous enough for the particular range to be disclaimed. For similar reasons, the CAFC also found no disclaimer of “signals that are generated from positional change information, user selection information, physiological response information, and other slow-varying information,” which had not been directly addressed in the inventor’s argument.

The CAFC concluded that the district court erred in the claim construction and that the proper scope of the term “input signal” is “a signal having an audio or higher frequency.”

Takeaway

This case provides a reminder that caution should be taken not to make “clear and unmistakable” statements in arguing around the prior art during prosecution. Although there appears to be no fixed criteria for assessing what qualifies as a “clear and unmistakable” disavowal, applicant’s consistency in presenting one main argument—focused on an essential distinction between the claim and the prior art—without introducing unnecessary details may help limit the extent of potential prosecution disclaimer.

CAFC relies on extrinsic evidence to define a claim term and to demonstrate inherency

| February 23, 2018

Monsanto Technology LLC v. E.I. Dupont de Nemours & Co.

January 5, 2018

Before Dyke, Reyna and Wallach. Opinion by Wallach.

Summary

In this case, the CAFC affirmed a PTAB decision which relied on two pieces of extrinsic evidence. First, a journal article referred to by the specification was used to define the bounds of “about 3% or less.” Second, a Declaration submitted in the course of inter partes reexamination was used to demonstrate that claimed features are inherent in an anticipating reference. The CAFC explained that both were appropriate, and the claims are invalid as being anticipated by the cited art.

Definition in specification trumps asserted meaning to a person of ordinary skill in the art and the doctrine of claim differentiation.

| June 10, 2016

Ruckus Wireless, Inc. v. Innovative Wireless Solutions, LLC

May 31, 2016

Before Prost, Reyna, and Stark. Opinion by Reyna, Dissent by Stark.

Summary

The specification consistently characterized “communications path” in terms of wired connections. In the absence of any evidence, either intrinsic or extrinsic, to the contrary, these characterizations are understood as definitional and limit “communications path” to a wired connection.

Details

The patent in suit: Innovative Wireless Solutions (“IWS”) owns U.S. Patent Nos. 5,912,895; 6,327,264; and 6,587,473 (the “Terry patents”), directed to techniques for providing access to a local area network (“LAN”) from a relatively distant computer, using an approach by which a “master” modem in the LAN dictates the timing of one-way communications between the master modem and a “slave” modem in the distant computer.

The patents, which are related to each other as parent and continuations, only describe connecting the master and slave modems over physical wires, such as a telephone line, and make no mention of wireless communications, but the claims recite that the two modems are connected via a “communications path.”

Issue at trial: The central dispute during claim construction was whether the recited “communications path” captures wireless communications or is limited to wired communication.

Ruckus argued “that its wireless equipment does not infringe the Terry patents because the Terry patents are limited to wired rather than wireless communications.”

The district court’s claim construction: The district court based its claim interpretation on intrinsic evidence, primarily the specification, which repeatedly refers to “two-wire lines and telephone lines,” and with respect to alternative embodiments says that “although as described here the line 12 is a telephone subscriber line, it can be appreciated that the same arrangement of master and slave modems operating in accordance with the new protocol can be used to communicate Ethernet frames via any twisted pair wiring which is too long to permit conventional 10BASE-T or similar LAN interconnections.”

The district court construed “communications path” to mean “communications path utilizing twisted-pair wiring that is too long to permit conventional 10BASE-T or similar LAN (Local Area Network) interconnections.”

The CAFC’s opinion: Because the district court relied on intrinsic evidence, its claim construction was a legal determination reviewed de novo by the CAFC.

Claim interpretation is based on the ordinary and customary meaning of the words in a claim, which is “the meaning that the term would have to a person of ordinary skill in the art in question at the time of the invention,” but importantly, within the context of the patent. The CAFC pointed out that it is legal error to rely “on extrinsic evidence that contradicts the intrinsic record.”

IWS presented three arguments on appeal:

- The district court imported the wired limitation into the claims, thereby committing reversible error.

- The district court read a “wired” limitation into the claims on the basis that every disclosed embodiment was wired, thereby committing reversible error.

- Several dependent claims limited the communications path to wired lines, so the doctrine of claim differentiation requires that the independent claims to be interpreted not to be so limited.

Ruckus argued that “communications path” does not actually have a plain and ordinary meaning to a person of ordinary skill in the art and that the specification limited the scope of “communications path” to a wired connection. It also countered the “claim differentiation” argument by pointing out that the type of wired line recited in the dependent claims is only one of several types disclosed in the specification, so that all that the doctrine of claim differentiation requires is that the “communication path” not be limited to the type of wired line recited in the dependent claims.

The CAFC agreed with Ruckus that IWS could not point to any intrinsic or extrinsic evidence in support of an ordinary meaning for “communications path” encompassing both wired and wireless communications, and that the dependent claims merely exclude other types of wired communications disclosed in the patents; and agreed with the district court that the intrinsic evidence (specifically, the specification’s description of the invention) strongly supported an understanding that “communications path” must be a wired connection.

Finally, the CAFC pointed out that the canons of claim construction require that “if, after applying all other available tools of claim construction, a claim is ambiguous, it should be construed to preserve its validity”; but that “[b]ecause the specification makes no mention of wireless communications, construing the instant claims to encompass that subject matter would likely render the claims invalid for lack of written description.”

The CAFC accordingly affirmed the district court’s claim interpretation and final judgment of noninfringement.

Dissent: The dissent states that the district court’s judgment should have been vacated and the case remanded to the district court to provide the parties an opportunity to present extrinsic evidence on the meaning of “communications path.”

Take-away

When preparing an application, check dictionaries and do an online search to verify that terms used to designate elements of the invention have a well-understood meaning. If a term does not have a well-understood meaning, be aware that descriptions of the element and its embodiments may be viewed as implicit definitions that limit its scope.

Tags: claim construction > claim differentiation > extrinsic evidence > intrinsic evidence > ordinary meaning

Definitional Language In The Specification May Be Fully Determinative Of Claim Construction

| December 9, 2015

CardSoft, LLC v. VeriFone, Inc.

December 2, 2015

CAFC Panel and opinion author: Prost, Taranto, and Hughes, Opinion by Hughes

Summary

On remand from the Supreme Court, the Federal Circuit again reverses the district court’s construction of the term “virtual machine” and gives “virtual machine” its ordinary and customary meaning, resulting in a judgment of no infringement.

Tags: claim differentiation > de novo > extrinsic evidence > ordinary and

Prior art can show what the claims would mean to those skilled in the art

| December 5, 2012

ArcelorMittal v. AK Steel Corp.

November 30, 2012

Panel: Dyk, Clevenger, and Wallach. Opinion by Dyk.

Summary:

The U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware held that defendants AK Steel did not infringe plaintiffs ArcelorMittal’s U.S. Patent No. 6,296,805 (the ‘805 patent), and that the asserted claims were invalid as anticipated and obvious based on a jury verdict.

ArcelorMittal appealed the district court’s decision. On appeal, the CAFC upheld the district court’s claim construction in part and reverse it in part. With regard to anticipation, the CAFC reversed the jury’s verdict of anticipation. With regard to obviousness, the CAFC held that a new trial is required because the district court’s claim construction error prevented the jury from properly considering ArcelorMittal’s evidence of commercial success.

미국 델라웨어주 연방지방법원 (U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware)은 원고 (ArcelorMittal)가 피고 (AK Steel)를 상대로 낸 특허 침해 소송에서 원고의 특허 (U.S. Patent No. 6,296,805)가 예견가능성 (anticipation) 및 자명성 (obviousness) 기준을 통과하지 못하였다는 배심원의 판단을 바탕으로 피고가 원고의 특허를 침해하지 않았다고 판결하였다.

이에 불복하여 원고는 연방항소법원 (U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit)에서 상고 (appeal) 하였으며, 연방항소법원은 지방법원의 청구항 해석 (claim construction)에 대해 일정 부분은 확인하였으나, 나머지 부분은 번복하였다.

예견가능성과 관련하여 연방항소법원은 배심원의 예견가능성 판단과 다른 결정을 내렸다.

자명성과 관련해서는 연방지방법원의 잘못된 청구항 해석으로 인하여 배심원이 원고의 상업적 성공 (commercial success) 증거를 고려하지 않았기때문에 재심 (new trial)이 필요하다고 판결하였다.