FUNCTIONAL CLAIMS REQUIRE MORE THAN JUST TRIAL-AND-ERROR INSTRUCTIONS FOR SATISFYING THE ENABLEMENT REQUIREMENT

| January 5, 2024

Baxalta Inc. v. Genentech, Inc.

Decided: September 20, 2023

Moore, Clevenger and Chen. Opinion by Moore

Summary:

Baxalta sued Genentech alleging that Genentech’s Hemlibra product infringes US Patent No. 7,033,590 (the ‘590 patent). Genentech moved for summary judgment of invalidity of the claims for lack of enablement. The district court granted summary judgment of invalidity. Upon appeal to the CAFC, the CAFC affirmed invalidity for lack of enablement citing the recent Supreme Court case Amgen v. Sanofi.

Details:

Baxalta’s patent is to a treatment for Hemophilia A. Blood clots are formed by a series of enzymatic activations known as the coagulation cascade. In a step of the cascade, enzyme activated Factor VIII (Factor VIIIa) complexes with enzyme activated Factor IX (Factor IXa) to activate Factor X. Hemophilia A causes the activity of Factor VIII to be functionally absent which impedes the coagulation cascade and the body’s ability to form blood clots. Traditional treatment includes administering Factor VIII intravenously. But this treatment does not work for about 20-30% of patients.

The ‘590 patent provides an alternative treatment. The treatment includes antibodies that bind to Factor IX/IXa to increase the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa which allows Factor IXa to activate Factor X in the absence of Factor VIII/VIIIa. Claim 1 of the ‘590 patent is provided:

1. An isolated antibody or antibody fragment thereof that binds Factor IX or Factor IXa and increases the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa.

The ‘590 patent describes that the inventors performed four hybridoma fusion experiments using a prior art method. And using routine techniques, the inventors screened the candidate antibodies from the four fusion experiments to determine whether the antibodies bind to Factor IX/IXa and increase procoagulant activity as claimed. Only 1.6% of the thousands of screened antibodies increased the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa. The ‘590 patent discloses the amino acid sequences of eleven antibodies that bind to Factor IX/IXa and increase the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa.

Citing Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, 598 U.S. 594 (2023), the CAFC stated that “the specification must enable the full scope of the invention as defined by its claims, allowing for a reasonable amount of experimentation. Citing additional cases, the CAFC stated “in other words, the specification of a patent must teach those skilled in the art how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without undue experimentation.”

Baxalta argued that one of ordinary skill in the art can obtain the full scope of the claimed antibodies without undue experimentation because the patent describes the routine hybridoma-and-screening process. However, the CAFC stated that the facts of this case are indistinguishable from the Amgen case in which the patent at issue provided two methods for determining antibodies within the scope of the claims. In Amgen, the Supreme Court stated that the two disclosed methods were “little more than two research assignments,” and thus, the claims fail the enablement requirement.

The CAFC described the claims in this case as covering all antibodies that (1) bind to Factor IX/IXa; and (2) increase the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa, and that “there are millions of potential candidate antibodies.” The specification only discloses amino acid sequences for eleven antibodies within the scope of the claims. Regarding the method for obtaining the claimed antibodies, the specification describes the following steps:

(1) immunize mice with human Factor IX/IXa;

(2) form hybridomas from the antibody-secreting spleen cells of those mice;

(3) test those antibodies to determine whether they bind to Factor IX/IXa; and

(4) test those antibodies that bind to Factor IX/IXa to determine whether any increase procoagulant activity.

The CAFC stated that similar to Amgen, this process “simply directs skilled artisans to engage in the same iterative, trial-and-error process the inventors followed to discover the eleven antibodies they elected to disclose.”

The Supreme Court in Amgen also stated that the methods for determining antibodies within the scope of the claims might be sufficient to enable the claims if the specification discloses “a quality common to every functional embodiment.” However, no such common quality was found in the ‘590 patent that would allow a skilled artisan to predict which antibodies will perform the claimed functions. Thus, the CAFC concluded that the disclosed instructions for obtaining claimed antibodies, without more, “is not enough to enable the broad functional genus claims at issue here.”

Baxalta further argued that its process disclosed in the ‘590 patent does not require trial-and-error because the process predictably and reliably generates new claimed antibodies every time it is performed. The CAFC stated that even if a skilled artisan will generate at least one claimed antibody each time they follow the disclosed process, “this does not take the process out of the realm of the trial-and-error approaches rejected in Amgen.” “Under Amgen, such random trial-and-error discovery, without more, constitutes unreasonable experimentation that falls outside the bounds required by § 112(a).”

Baxalta also argued that the district court’s enablement determination is inconsistent with In re Wands. The CAFC disagreed stating that the facts of this case are more analogous to the facts in Amgen, and the Amgen case did not disturb prior enablement case law including In re Wands and its factors.

Comments

When claiming a product functionally, make sure your specification includes something more than just trial-and-error instructions. The CAFC suggested in this case that the enablement requirement may be satisfied if the patent discloses a common structural or other feature delineating products that satisfy the claims from products that will not. The CAFC also suggested that a description about why the actual disclosed products perform the claimed functions or why other products do not perform the claimed function would be helpful for satisfying the enablement requirement.

THE MORE YOU CLAIM, THE MORE YOU MUST ENABLE

| July 12, 2023

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi

Decided: May 18, 2023

Supreme Court of the United States. Opinion by Justice Gorsuch

Summary:

Amgen owns patents covering antibodies that help reduce levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Amgen sued Sanofi for infringement of its patents in district court. Sanofi raised the defense of invalidity for lack of enablement because while Amgen provided amino acid sequences for 26 antibodies, the claims cover potentially millions more undisclosed antibodies. The district court granted a motion for JMOL for invalidity due to lack of enablement, the CAFC affirmed, and the Supreme Court affirmed.

Details:

Amgen’s patents are to PCSK9 inhibitors. PCSK9 is a naturally occurring protein that binds to and degrades LDL receptors. PCSK9 causes problems due to degradation of LDL receptors because LDL receptors extract LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream. A method used to inhibit PCSK9 is to create antibodies that bind to a particular region of PCSK9 referred to as the “sweet spot” which is a sequence of 15 amino acids out of PCSK9’s 692 total amino acids. An antibody that binds to the sweet spot can prevent PCSK9 from binding to and degrading LDL receptors. Amgen developed a drug named REPATHA and Sanofi developed a drug named PRALUENT, both of which provide a distinct antibody with its own unique amino acid sequence. In 2011, Amgen and Sanofi received patents covering the antibody used in their respective drugs.

The patents at issue are U.S. Patent Nos. 8,829,165 and 8,859,741 issued in 2014 which relate back to Amgen’s 2011 patent. These patents are different from the 2011 patents in that they claim the entire genus of antibodies that (1) “bind to specific amino acid residues on PCSK9,” and (2) “block PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.” The relevant claims are provided:

Claims of the ‘165 patent:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein, when bound to PCSK9, the monoclonal antibody binds to at least one of the following residues: S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of SEQ ID NO:3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

19. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 1 wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds to at least two of the following residues S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of PCSK9 listed in SEQ ID NO:3.

29. A pharmaceutical composition comprising an isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds to at least two of the following residues S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of PCSK9 listed in SEQ ID NO: 3 and blocks the binding of PCSK9 to LDLR by at least 80%.

Claims of the ‘741 patent:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody that binds to PCSK9, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds an epitope on PCSK9 comprising at least one of residues 237 or 238 of SEQ ID NO: 3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

2. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 1, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody is a neutralizing antibody.

7. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 2, wherein the epitope is a functional epitope.

In its application, Amgen identified the amino acid sequences of 26 antibodies that perform these two functions. Amgen provided two methods to make other antibodies that perform the described binding and blocking functions. Amgen refers to the first method as the “roadmap,” which provides instructions to:

(1) generate a range of antibodies in the lab; (2) test those antibodies to determine whether any bind to PCSK9; (3) test those antibodies that bind to PCSK9 to determine whether any bind to the sweet spot as described in the claims; and (4) test those antibodies that bind to the sweet spot as described in the claims to determine whether any block PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.

Amgen refers to the second method as “conservative substitution” which provides instructions to:

(1) start with an antibody known to perform the described functions; (2) replace select amino acids in the antibody with other amino acids known to have similar properties; and (3) test the resulting antibody to see if it also performs the described functions.

Amgen sued Sanofi for infringement of claims 19 and 29 of the ‘165 patent and claim 7 of the ‘741 patent. Sanofi raised the defense of invalidity because Amgen had not enabled a person skilled in the art to make and use all of the antibodies that perform the two functions Amgen described in the claims. Sanofi argued that Amgen’s claims cover potentially millions more undisclosed antibodies that perform the same two functions than the 26 antibodies identified in the patent.

The court provided an explanation of the law and policy regarding the enablement requirement. 35 U.S.C. § 112 requires that a specification include “a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art … to make and use the same.” The court stated:

the law secures for the public its benefit of the patent bargain by ensuring that, upon the expiration of [the patent], the knowledge of the invention [i]nures to the people, who are thus enabled without restriction to practice it.

The court stated that “the specification must enable the full scope of the invention as defined by its claims.” Specifically, the court stated:

If a patent claims an entire class of processes, machines, manufactures, or compositions of matter, the patent’s specification must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the entire class.

The court emphasized that the enablement requirement does not always require a description of how to make and use every single embodiment within a claimed class. A few examples may suffice if the specification also provides “some general quality … running through” the class. A specification may also not be inadequate just because it leaves a skilled artisan to engage in some measure of adaptation or testing, i.e., a specification may call for a reasonable amount of experimentation to make and use a patented invention. “What is reasonable in any case will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art.”

Regarding this case, the court stated that while the 26 exemplary antibodies provided by Amgen are enabled by the specification, the claims are much broader than the specific 26 antibodies. And even allowing for a reasonable degree of experimentation, Amgen has failed to enable the full scope of the claims.

The court stated that Amgen seeks to monopolize an entire class of things defined by their function and that this class includes a vast number of antibodies in addition to the 26 that Amgen has described by their amino acid sequences. “[T]he more a party claims, the broader the monopoly it demands, the more it must enable.”

Amgen argued that the claims are enabled because scientists can make and use every undisclosed but functional antibody if they simply follow Amgen’s “roadmap” or its proposal for “conservative substitution.” The court stated that these instructions amount to two research assignments and that they leave scientists “forced to engage in painstaking experimentation to see what works.” The court referred to Amgent’s two methods as “a hunting license.”

Comments

The key takeaway from this case is that the broader your claims are, the more your specification must enable. If it is difficult to show enablement for every embodiment claimed, then make sure your specification describes some general quality throughout the class or genus. A reasonable amount of experimentation is permissible for enablement, but reasonableness will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art.

File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products

| May 26, 2023

Minerva Surgical, Inc. v. Hologic, Inc., Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC

Decided: February 15, 2023

Summary:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”). Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b). The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because the patented technology was “in public use,” and the technology was “ready for patenting.” The Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of their constituted the invention being “in public use,” and that the device was “ready for patenting.” Therefore, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment.

Details:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”).

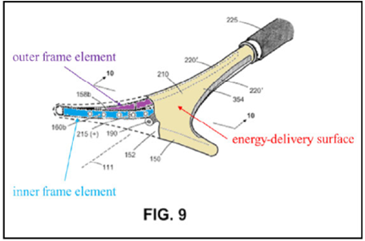

The ’208 patent is directed to surgical devices for a procedure called “endometrial ablation” for stopping or reducing abnormal uterine bleeding. This procedure includes inserting a device having an energy-delivery surface into a patient’s uterus, expanding the surface, energizing the surface to “ablate” or destroy the endometrial lining of the patient’s uterus, and removing the surface.

The application for the’208 patent was filed on November 2, 2021 and claims a priority date of November 7, 2011. Therefore, the critical date for the ’208 patent is November 7, 2010.

The ’208 patent

Independent claim 13 is a representative claim:

A system for endometrial ablation comprising:

an elongated shaft with a working end having an axis and comprising a compliant energy-delivery surface actuatable by an interior expandable-contractable frame;

the surface expandable to a selected planar triangular shape configured for deployment to engage the walls of a patient’s uterine cavity;

wherein the frame has flexible outer elements in lateral contact with the compliant surface and flexible inner elements not in said lateral contact, wherein the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties.

The appeal focused on the claim term, “the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties” (“SDMP” term”).

District Court

After discovery, Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b).

The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because of the following reasons:

First, the patented technology was “in public use” because Minerva disclosed fifteen devices (“Aurora”) at an event, where Minerva showcased them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation. Also, Minerva did not disclose them under any confidentiality obligations.

Second, the technology was “ready for patenting” because Minerva created working prototypes and enabling technical documents.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reviewed a district court’s grant of summary judgment under the law of the regional circuit (Third Circuit).

The Federal Circuit held that “the public use bar is triggered ‘where, before the critical date, the invention is [(1)] in public use and [(2)] ready for patenting.’”

The “in public use” element is satisfied if the invention “was accessible to the public or was commercially exploited” by the invention.

“Ready for patenting” requirement can be shown in two ways – “by proof of reduction to practice before the critical date” and “by proof that prior to the critical date the inventor had prepared drawings or other descriptions of the invention that were sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention.”

The Federal Circuit held that disclosing the Aurora device at the event (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (“AAGL 2009”)) constituted the invention being “in public use” because this event included attendees who were critical to Minerva’s business, and Minerva’s disclosure of their devices included showcasing them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation.

The Federal Circuit noted that AAGL 2009 was the “Super Bowl” of the industry and was open to the public, and that Minerva had incentives to showcase their products to the attendees. Also, Minerva sponsored a presentation by one of their board members to highlight their products and pitched their products to industry members, who were able to see how they operate.

The Federal Circuit also noted that there were no “confidentiality obligations imposed upon” those who observed Minerva’s devices, and that the attendees were not required to sign non-disclosure agreements.

The Federal Circuit also held that Minerva’s Aurora devices at the event disclosed the SDMP term because Minerva’s documentation about this device from before and shortly after the event disclosed this device having the SDMP terms or praises benefits derived from this device having the SDMP technology.

The Federal Circuit held that the record clearly showed that Minerva reduced the invention to practice by creating working prototypes that embodied the claim and worked for the intended purpose.

The Federal Circuit noted that there was documentation “sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention” of the disputed SDMP term. Here, the documentation included the drawings and detailed descriptions in the lab notebook pages disclosing a device with the SDMP term.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of the Aurora device constituted the invention being “in public use” and that the device was “ready for patenting.”

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment because there are no genuine factual disputes, and Hologic is entitled to judgment as a matter of law that the ’208 patent is anticipated under the public use bar of § 102(b).

Takeaway:

- File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products.

- Have the attendees of the trade show sign non-disclosure agreements, if necessary.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) > confidentiality > critical date > enablement > pre-AIA > prototype > public use > reduction to practice > summary judgment

Broad functional limitations in claims “raise the bar for enablement”

| April 13, 2021

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi

February 11, 2021

Before Prost, Lourie, and Hughes (Opinion by Lourie).

Summary

The Federal Circuit invalidates genus claims with functional limitations for lacking enablement. The Federal Circuit focuses the enablement analysis on the broad scope of structures covered by the claims and the lack of guidance in the specification on how to identify those structures that exhibit the claimed functionalities.

Details

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol is often called the “bad” cholesterol. An elevated LDL level leads to fatty buildups (or plaques) in arteries and contributes to heart disease. LDL receptors remove LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream and regulates the amount of LDL cholesterol in circulation.

The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) enzyme has for years been an important cholesterol-lowering target. The PCSK9 enzyme degrades LDL receptors and can interfere with the regulation of circulating LDL cholesterol levels. It has been found that loss-of-function mutations in the PCSK9 enzyme lead to higher levels of the LDL receptor, lower circulating LDL cholesterol levels, and protection from heart disease.

U.S. Patent Nos. 8,829,165 and 8,859,741, owned by Amgen Inc., relate to antibodies that bind to and block PCSK9 to inhibit PCSK9-LDL receptor interactions.

The relevant claims in the 165 and 741 are all directed to an antibody, and all define the antibody in terms of two specific functions: first, the antibody “binds to” a combination of amino acid residues on the PCSK9 protein, and second, the antibody “blocks” binding of PCSK9 to LDL receptor.

For example, independent claim 1 of the 165 patent recites:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein, when bound to PCSK9, the monoclonal antibody binds to at least one of the following residues: S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of SEQ ID NO:3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

Independent claim 29 of the 165 patent specifically requires that the antibody blocks the binding of PCSK9 to LDL receptor by at least 80%.

Independent claim 1 of the 741 patent recites:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody that binds to PCSK9, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds an epitope on PCSK9 comprising at least one of residues 237 or 238 of SEQ ID NO: 3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

The 165 and 741 patents share a common written description. The specifications disclose 26 specific antibodies, including their production, screening, and amino acid sequences. For only 2 of those antibodies, the specifications disclose the 3D structures showing the binding of the antibodies to specific PCSK9 residues. The examples test the binding of only 3 antibodies to PCSK9.

Another one of Amgen’s patents, not at issue in this case, claims Repatha®, which is a PCSK9 inhibitor that Amgen currently markets as a prescription injection therapy for treating adults with high cholesterol. Amgen used to sell Repatha® for $14,520, but to stay “competitive” with other drug makers’ PCSK9 inhibitors, Amgen lowered the price tag to $5,850 in 2020. Amgen still made nearly $900 million from Repatha® in 2020.

Repatha® is exemplified in the 165 and 741 patents, but not claimed. And whereas Amgen’s Repatha patent claims the amino acid sequence of the antibody, the 165 and 741 patents at issue in this case do not define the antibodies in terms of their amino acid sequences. Rather, the 165 and 741 patent claims use functional language to recite an entire genus of antibodies that bind to specific amino acid residues on PCSK9 and block PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.

The use of functional limitations is central to the Federal Circuit’s affirmance of the district court’s determination that the 165 and 741 patent claims lack enablement.

The Federal Circuit begins with the usual reiteration of the Wands factor for evaluating enablement:

- the quantity of experimentation necessary;

- the amount of direction or guidance presented;

- the presence or absence of working examples;

- the nature of the invention;

- the state of the prior art;

- the relative skill of those in the art;

- the predictability or unpredictability of the art; and

- the breadth of the claims.

The Federal Circuit then compares the facts of the case to several precedents:

- Wyeth & Cordis Corp. v. Abbott Laboratories, 720 F.3d 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2013);

- Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. v. Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., 928 F.3d 1340 (Fed. Cir. 2019); and

- Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Gilead Sciences Inc., 941 F.3d 1149 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

In each of those precedents, the claims required both a particular structure and functionality. And in each case, the Federal Circuit found that the claims were not enabled, because the large number of embodiments within the scope of the claims and the specification’s lack of guidance on the structure/function correlation would have required undue experimentation to determine which embodiments would exhibit the required functionality.

None of these precedents are favorable to Amgen. The precedents, together with Sanofi’s argument that the binding limitation in Amgen’s claims alone encompasses “millions” of antibodies, effectively focuses the Federal Circuit’s attention on the breadth of Amgen’s patent claims:

While functional claim limitations are not necessarily precluded in claims that meet the enablement requirement, such limitations pose high hurdles in fulfilling the enablement requirements for claims with broad functional language…

Turning to the specific Wands factors, we agree with the district court that the scope of the claims is broad. While in and of itself this does not close the analysis, the district court properly considered that these claims were indisputably broad… However, we are not concerned simply with the number of embodiments but also with their functional breadth. Regardless of the exact number of embodiments, it is clear that the claims are far broader in functional diversity than the disclosed examples. If the genus is analogized to a plot of land, the disclosed species and guidance “only abide in a corner of the genus.” Further, the use of broad functional claim limitations raises the bar for enablement, a bar that the district court found was not met.

Amgen argues that the specifications provide “roadmap” for making the claimed antibodies, but the problem, as the Federal Circuit sees it, is that even after the antibodies are made, identifying those specific antibodies that exhibit the claimed functionalities of binding and blocking PCSK9 is only possible through laborious “trial and error” requiring “substantial time and effort”.

Amgen is not helped by seemingly undisputed expert testimony on the unpredictability of the art. There appears to be agreement between the two sides’ experts that a small modification in an antibody’s sequence can result in big changes in structure and functions. Further, there is evidence that translating an antibody’s amino acid sequence into a known 3D structure is still not possible, so that it is difficult to visualize and evaluate the binding of an antibody to PCSK9. As the Federal Circuit articulates, “the enablement inquiry for claims that include functional requirements can be particularly focused on the breadth of those requirements, especially where predictability and guidance fall short.”

There are some interesting observations.

First, while the patents at issue clearly claim a biotech invention, the Federal Circuit’s decision cites frequently to McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games Am. Inc., 959 F.3d 1091 (Fed. Cir. 2020)—a computer case—for its discussion on the enablement of a claimed range. However, in McRO, the Federal Circuit did not even address the question of whether the disputed claims were enabled. The Federal Circuit held only that the enablement analysis required first delineating the precise scope of the claimed invention, and having failed to make that delineation, the district court’s summary determination of non-enablement must be vacated.

Second, at first glance, the Federal Circuit appears to have articulated a “heightened” standard of enablement for claims reciting functional limitations. But really, the “heightened” bar seems to be no more than a proposition that the broader the claim, the more guidance the specification may need to provide to satisfy the enablement requirement.

Third, during prosecution of the 165 patent, the Examiner rejected the claims as lacking enablement. However, Amgen overcame the rejection by arguing, without any Rule 132 declarations, that “various antibodies” and “crystal structures” provided in the specification explained how antibodies bound to PCSK9 to achieve the claimed functionalities.

Takeaway

- The use of functional limitations, while desirable for imparting breadth to a claim, remains rife with pitfalls. For certain types of claims, such as claims directed to biologics, functional limitations are almost unavoidable because claiming the invention strictly in structural terms would be unduly narrow. For those claims, details in the specification are especially important.

- Where a claim requires both a particular structure and functionality, the specification should preferably describe some correlation between the structure and the claimed functionality.

- Where a claim recites a broad genus of structures for achieving a specific function, it is important for the specification to exemplify more than one species within that genus. Ideally the specification should also describe structural characteristics common to the species of the genus.

A patent specification need enable full scope of the claimed invention

| August 10, 2018

Trustees of Boston University. v. Everlight Electronics Co. Ltd., et al.

July 25, 2018

Before Prost, Moore, and Reyna. Opinion by Prost.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s denial of Defendants’ motion for JMOL that claim 19 of the asserted patent is invalid for failing to meet the enablement requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112 because the specification fails to enable full scope of the claimed invention.

When is Evidence of Written Description Too Late?

| October 24, 2017

Amgen v. Sanofi

October 5, 2017

Before Prost, Taranto and Hughes. Opinion by Judge Prost.

Procedural History:

The two patents-in-suit disclose and claim a set of antibodies. The following claim is representative:

An isolated monoclonal antibody,

wherein, when bound to PCSK9, the monoclonal antibody binds to at least one of the following residues: S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of SEQ ID NO:3, and

wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDL[-]R.

The technical background of the invention involves statins that are administered to patients to reduce high levels of LDL-C in the blood. When these statins do not work, doctors sometimes administer PCSF9 inhibitor as well – PCSK9 being a naturally occurring protein that binds to and destroys liver cell LDL-receptors that take LDL-C from the blood.

The claim recites a genus of antibodies that bind to PCSK9 at the recited residue sites, thereby preventing PCSK9 from interfering with LDL-C removal from the blood.

The specification, common to both patents, discloses “85 antibodies that blocked interaction between the PCSK9 . . . and the LDLR [at] greater than 90%,” It also discloses the three-dimensional structures, obtained via x-ray crystallography, of two antibodies known to bind to residues recited in the claims—21B12 (Repatha) and 31H4.

Appellant/Defendant Sanofi markets an antibody named Praluent® alirocumab. Appellee/Patentee sued Sanofi for patent infringement. Sanofi replied, inter alia, that the claims did not comply with the written description and enablement requirements.

In a jury trial, the judge excluded from the evidentiary record all post-priority-date information that Sanofi proffered to show that the written description and enablement requirements were not met. Specifically, Sanofi’s proffered evidence that included its own later-developed Praluent product that was developed after the priority date of Amgen’s patents.

Ultimately, the jury issued a verdict that the patents were valid and infringed.

The CAFC reversed the trial judge’s exclusionary ruling and vacated the jury’s verdict. It first set forth the legal background, specifically, that a patentee must convey in its disclosure that it “had possession of the claimed subject matter as of the filing date” and that to provide this “precise definition” for a claim to a genus, a patentee must disclose “a representative number of species falling within the scope of the genus or structural features common to the members of the genus so that one of skill in the art can ‘visualize or recognize’ the members of the genus.” (Emphasis added).

Here, Sanofi’s evidence regarding Praluent was relevant to the material issue of whether the two patents disclosed a representative number of species within the claimed genus. The CAFC therefore held that the trial judge erred in excluding Sanofi’s evidence and ordered a new trial on written description. It also ordered a new trial on enablement for the same reasons.

The CAFC summarized the legal basis for its holding: evidence that explains the state of the art after the priority date is not relevant to written description. On the other hand, where a patent claims a genus, it must disclose “a representative number of species falling within the scope of the genus or structural features common to the members of the genus so that one of skill in the art can ‘visualize or recognize’ the members of the genus.” Accordingly, evidence showing that a claimed genus does not disclose a representative number of species may include evidence of species that fall within the claimed genus but are not disclosed by the patent, and evidence of such species is likely to postdate the priority date.

Take Away

The lesson is that the purpose for which post-priority date evidence is proffered determines whether it is admissible.

Nothing Lost but Nothing Gained: Generic Producer Evades Infringement but Fails to Invalidate Patent under §112.

| April 3, 2014

Alcon Research Ltd., v. Barr Laboratories, Inc.

March 18, 2014.

Before Newman, Lourie and Bryson. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary:

The CAFC reversed the District Court’s judgment that Alcon’s patents lacked enabling disclosure and sufficient written description as Barr had failed to demonstrate that some experimentation was required, let alone undue experimentation. Barr’s allegations that the claims were “too broad,” the specification was “too limited,” and the art was “too unpredictable,” was not sufficient without evidence to support that undue experimentation was required in order to practice the patented method.

The CAFC, however, affirmed the District Court’s judgment of non-infringement since Alcon had failed to prove that the polyethoxylated castor oil (“PECO)” in Barr’s product was present in a “chemically-stabilizing amount.”

The CAFC denied Barr’s judgment as a matter of law (“JMOL”) and Rule 59(e) (alter or amend a judgment) motions on non-infringement for the two patents that were omitted from the pretrial order and not litigated.

Improper NDA Defeats Trade Secrets and Overly Broad Patent Claims are Invalid

| July 29, 2013

Convolve v. Compaq Computer

July 1, 2013

Panel: Rader, Dyk and O’Malley. Opinion by O’Malley

Summary

Convolve, Inc. (“Convolve”) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (“MIT”) appeal the decision of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (“District Court”) granting summary judgment in favor of Compaq Computer Corp. (“Compaq”), Seagate Technology LLC. and Seagate Technology, Inc. (“Seagate”).

Convolve and MIT sued Compaq and Seagate in July 2000 for breach of contract; misappropriation of trade secrets listed in Amended Trade Secret Identification (ATSI); direct patent infringement; and inducement of patent infringement along with other complaints such as fraud; violation of California Business and Professions Code §17200 (“CA Unfair Competition”), etc.

In May 2006, the District Court disposed of all other charges from the suit except the breach of contract, misappropriation of trade secrets and patent infringement charges. The District Court later granted summary judgment in favor of Compaq and Seagate and dismissed the remaining charges. With regard to the trade secret charges, the District Court found that:

(1) some of Convolve’s trade secrets (ATSI 1B, 2A, 2C, 2E, and 3B-D) were covered under a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA), which Convolve failed to properly preserve according to the NDA procedures;

(2) some of Convolve’s trade secrets (ATSI 2A, 6B, and 7A) were public known or common knowledge in the industry, which were not entitled to protection;

(3) some of Convolve’s trade secrets were never used by the defendants (ATSI 2F and 7E); and

(4) because New York law does not extend trade secret protection to marketing concepts, some of the trade secrets alleged by Convolve are not recognized by the District Court.

With regard to the patent infringement charges, the District Court found that:

(1) out of the four models of products alleged by Convolve as infringing Patent’473, none read on the claims of the patent;

(2) Patent’635 was found invalid for being non-enabling based on the inventor’s testimony; and

(3) since no direct infringement was found, the claim for inducement of patent infringement must fail.

Taking all inference in favor of Convolve, the CAFC affirmed all counts of summary judgment with regard to the trade secret allegations, as well as the invalidity of Patent’635, but reversed the non-infringement decision about Patent’473.

Convolve (原告)与Compaq, Seagate(康柏电脑和希捷数码,被告)就原告开发的一些硬盘技术进行技术合作谈判,双方就谈判涉及内容签订了保密协议。但原告在向被告透露相关技术时没有严格按保密协定约定的程序处理涉密内容。后来改谈判未能达成一致,原告诉被告在谈判涉及的保密内容上侵犯商业机密及在另一些技术问题上专利侵权。一审结果,联邦区域法院裁定原告败诉。

上述法院均认定,尽管侵犯商业机密属于一个侵权法的范畴,然而在已签订合同中原被告双方均已同意以合同条款规定商业机密的范畴,故侵权法默认的商业机密标准不适用。因原告在履行保密协议过程中未遵循商定的处理程序,原告在此案中已丧失对该商业机密的索赔权。

另外, 关于专利侵权案,原告的专利在当年提出申请时对该发明的描述超过了发明人的当时可以实施实际该发明的范畴,故该专利被认定未能适当描述其实施方法因而无效。上述法院部分维持一审法院的判决。

Tags: enablement > NDA > non-disclosure agreement > trade secret

CAFC clarifies the presumption that prior art is enabled after In re Antor Media Corp (Fed. Cir. 2012)

| April 10, 2013

In re Steve Morsa

April 5, 2013

Panel: Rader, Lourie and O’Malley. Opinion by O’Malley.

Summary

The Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (“Board”) had affirmed an Examiner’s finding that a short press release, relied on for an anticipation rejection, was enabling. In making its decision, the Board had held that arguments alone by the applicant were insufficient to rebut the presumption that a reference was enabling. The CAFC found that the Board and the examiner had failed to engage in a proper enablement analysis of the reference and vacated the anticipation finding.

Tags: affidavit > declaration > declaration and affidavit > enablement > evidence to overcome presumption of enablement > non-enabling prior art > presumption of enablement

Like prior art patents, potentially anticipatory non-patent printed publications are presumed to be enabling

| October 5, 2012

In re Antor Media Corporation

July 27, 2012

Panel: Rader, Lourie and Bryson. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary

Antor Media Corp. appeals from the decision of the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences rejecting on reexamination the claims of its patent as anticipated and obvious over four prior art references. The prior art references include three printed publications and one U.S. patent. The Board found that two of the printed publications anticipated the claims in Antor’s patent. Here, Antor argues that since the printed publications are not enabling, they could not have anticipated the claims. Antor further argues that unlike prior art patents, prior art printed publications are not presumptively enabling. The principal issue on appeal is therefore whether the presumption that prior art patents are enabling can be logically extended to printed publications. The Federal Circuit answers that it can, holding that a prior art printed publication cited by an examiner is presumptively enabling barring any showing to the contrary by a patent applicant or patentee.

Tags: anticipation > enablement > non-enablement > non-patent literature > prior art