DESIGN CLAIM IS LIMITED TO AN ARTICLE OF MANUFACTURE IDENTIFIED IN THE CLAIM

| November 8, 2021

In Re: Surgisil, L.L.P., Peter Raphael, Scott Harris

Decided on October 4, 2021

Moore (author), Newman, and O’Malley

Summary:

The Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB’s anticipation decision on a claim of SurgiSil’s ’550 application because a design claim should be limited to an article of manufacture identified in the claim. The Federal Circuit held that since the claim in the ’550 application identified a lip implant, the claim is limited to lip implants and does not cover other article of manufacture. The CAFC held that since the Blick reference discloses an art tool rather than a lip implant, the PTAB’s anticipation finding is not correct.

Details:

The ’550 application

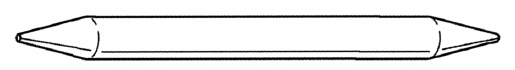

SurgiSil’s ’550 application claims an ornamental design for a lip implant[1] as shown below:

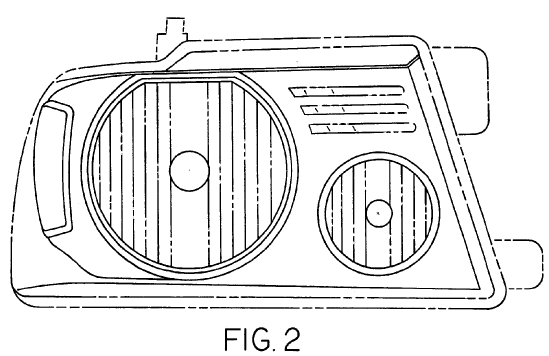

The examiner rejected a claim of the ’550 application as being anticipated by Blick, which discloses an art tool called stump as shown below:

The PTAB

The PTAB affirmed the examiner’s decision and found that the differences between the claimed design in the ’550 application and Blick are minor.

The PTAB rejected SurgiSil’s argument that Blick discloses a “very different” article of manufacture than a lip implant reasoning that “it is appropriate to ignore the identification of manufacture in the claim language” and “whether a reference is analogous art is irrelevant to whether that reference anticipates.”

The Federal Circuit

The CAFC reviewed the PTAB’s legal conclusion that the article of manufacture identified in the claims is not limiting de novo. The CAFC ultimately held that the PTAB erred as a matter of law.

By citing 35 U.S.C. §171(a) (“Whoever invents any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.”), the CAFC held that a design claim is limited to the article of manufacture identified in the claim.

The CAFC also cited a case called Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc., 938 F.3d 1334, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2019)[2] and the MPEP to hold that the claim at issue should be limited to the particular article of manufacture identified in the claim.

The CAFC held that since the claim identified a lip implant, the claim is limited to lip implants and does not cover other article of manufacture.

The CAFC held that since Blick discloses an art tool rather than a lip implant, the PTAB’s anticipation finding is not correct.

Therefore, the CAFC reversed the PTAB’s decision.

Takeaway:

- It would certainly be easier to obtain design patents going forward. Can Applicant obtain design patents by using a known design in the art and applying to a new article of manufacture?

- It would be difficult to invalidate design patents because prior arts from a different article of manufacture could not be used to invalidate them.

- Applicant should be careful to amend a title/claim and provide any description on title/terms in the claim in a design application because they could be used to construe an article of manufacture and to clarify the scope of a design patent claim.

- It may be difficult to enforce the design patent for a certain article of manufacture (i.e., “lip implant”) against a different article of manufacture (“art stump”).

[1] Website for SurgiSil: SurgiSil’s silicone lip implants are an alternative to “repetitive, costly, and painful filler injections,” but that they can be removed at any time.

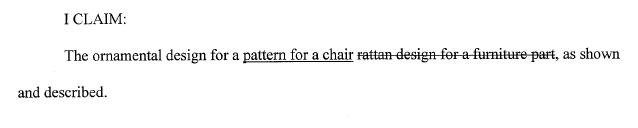

[2] In this case, the CAFC held that a particular claim was limited to a wicker pattern applied to an article of manufacture recited in the claim (chair) and did not cover the use of the same pattern on another non-claimed article (i.e., basket).

Same difference: A broad interpretation of “contrast” renders patented design obvious in view of prior art showing a similar “level of contrast”.

| October 19, 2020

Sealy Technology, LLC v. SSB Manufacturing Company (non-precedential)

August 26, 2020

Before Prost, Reyna, and Hughes (Opinion by Prost).

Summary

In nixing a design patent purporting to show “contrast” between design elements, the Federal Circuit broadly interprets “contrast” in the claimed design as not requiring a level of contrast that is different than what is available in the prior art.

Details

In their briefs to the Federal Circuit, Sealy Technology, LLC (“Sealy”) told the story about how, during a slump in sales around 2009, they re-designed their Stearns & Foster luxury-brand mattresses to visually distinguish their mattresses in a marketplace overrun with white or otherwise monochromatic mattress designs.

To be visually distinct, Sealy incorporated a “bold” combination of contrast edging running horizontally along the edges of the mattress and around the handles on the mattress.

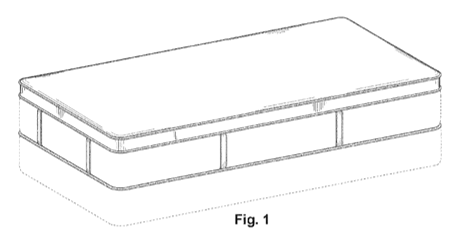

Sealy claimed this design in their U.S. Design Patent No. 622,531 (“D531 patent”). The D531 patent claimed “[t]he ornamental design for a Euro-top mattress design, as shown and described”, with Figure 1 being representative:

The D531 patent did not contain any textual descriptions of the contrast edging in Sealy’s mattress design.

Sealy’s dispute with Simmons Bedding Company (“Simmons”) began shortly after the D531 patent issued, when in 2010, Sealy sued Simmons for infringing the D531 patent. The product at issue was Simmons’s Beautyrest-brand mattress:

in 2011, Simmons sought an inter partes reexamination of the D531 patent. During the first round of the reexamination, the Examiner interpreted the claimed design as including the following elements:

- The horizontal piping along the edges of the top and bottom of the mattress and along the top flat surface of the pillow top layer has a contrasting appearance.

- The [eight] flat vertical handles each have contrasting sides of edges running vertically with the length of the handles.

However, the Examiner declined to adopt any of Simmons’s requested anticipation and obviousness challenges. And when Simmons appealed the Examiner’s refusal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, Sealy vouched for the Examiner’s interpretation.

Unfortunately for Sealy, the Board on appeal entered new obviousness rejections. A second round of the reexamination followed. This time around, the Examiner adopted the Board’s rejections, which Sealy was unable to overcome even after a second appeal to the Board. Sealy then appealed the rejections to the Federal Circuit.

Sealy raised two main issues on appeal: first, whether the Board correctly construed the “contrast” in the claimed design; and second, whether the cited prior art was a proper primary reference.

On the question of claim construction, the Board had determined that “the only contrast necessary is one of differing appearance from the rest of the mattress”, whether by contrasting fabric, contrasting color, contrasting pattern, and contrasting texture.

Sealy argued that the Board’s construction was too broad. The proper construction, argued Sealy, should require a more specific level of contrast, that is, “a contrasting value and/or color” or “something that causes the edge to stand out or to be strikingly different and distinct from the rest of the design”.

Sealy relied on MPEP 1503.02(II), which provides that “contrast in materials may be shown by using line shading in one area and stippling in another”, that “the claim will broadly cover contrasting surfaces unlimited by color”, and that “the claim would not be limited to specific material”. Sealy also argued that a designer of ordinary skill in the art would have understood the D531 patent as requiring a more specific degree of contrast than the Board’s construction.

The Federal Circuit disagreed.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Examiner and the Board’s findings that the patent contained no textual descriptions about contrast in the claimed design, that the drawings did not convey a different level of contrast than the prior art, and that Sealy’s argument regarding the understanding of a designer skilled in the art lacked evidentiary support..

On the question of obviousness, Sealy challenged the Board’s reliance on the Aireloom Heritage mattress shown below, arguing that the prior art mattress lacked the requisite contrast.

The weakness in Sealy’s argument was that its success depended entirely on the Federal Circuit adopting Sealy’s claim construction. And because the Federal Circuit did not find that the claimed design required a “strikingly different” contrast between the edging and the rest of the mattress, the Federal Circuit agreed with the Board’s determination that the prior art mattress had “at least some difference in appearance” between the edging and the rest of the mattress. This was sufficient to qualify the Aireloom Heritage mattress as a proper primary reference.

Takeaway

- Consider adding strategic textual descriptions in the specification to clarify the claimed design. For example, in Sealy’s case, since the contrast in the claimed design is provided in part by contrast in color, it may have been helpful to include such descriptions as “Figure 1 is a perspective view of a mattress showing a first embodiment f the Euro-top mattress design with portions shown in stippling to indicate color contrast”.

- If color contrast is important to the claimed design, consider adding solid black shading to the appropriate portions. 37 C.F.R. 1.152 (“Solid black surface shading is not permitted except when used to represent the color black as well as color contrast”).

- If the color scheme is important to the claimed design, consider filing a color drawing with the design application. One of Apple’s design patents on the iPhone graphical user interface includes a color drawing, which helped Apple’s infringement case against Samsung because similarities between the claimed design and the graphical user interface on Samsung’s Galaxy phones were immediately noticeable.

When there is competing evidence as to whether a prior art reference is a proper primary reference, an invalidity decision cannot be made as a matter of law at summary judgment

| April 29, 2020

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. v. Ultraproof, Inc., et al.

April 17, 2020

Newman, Lourie, Reyna (Opinion by Reyna; Dissent by Lourie)

Summary

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. (“Spigen”) sued Ultraproof, Inc. (“Ultraproof”) for infringement of its multiple patents directed to designs for cellular phone cases. The district court held that as a matter of law, Spigen’s design patents were obvious over prior art references, and granted Ultraproof’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity. However, based on the competing evidence presented by the parties, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) reversed and remanded, holding that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the primary reference was proper.

原告Spigen社は、自身の所有する複数の携帯電話ケースに関する意匠特許を被告Ultraproof社が侵害しているとして、提訴した。地裁は、原告の意匠特許は、先行技術文献により自明であるとして、裁判官は被告のサマリージャッジメントの申し立てを容認した。しかしながら、連邦控訴巡回裁判所(CAFC)は、双方の提示している証拠には「重要な事実についての真の争い(genuine dispute of material fact)」があるとして、地裁の判決を覆し、事件を差し戻した。

Details

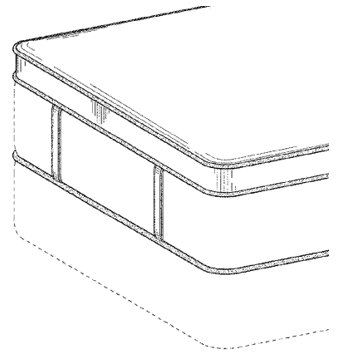

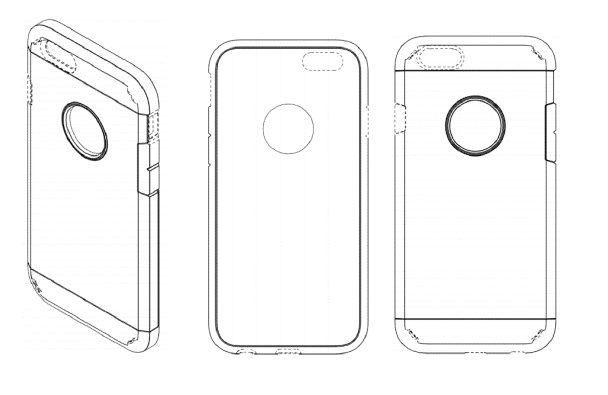

Spigen is the owner of U.S. Design Patent Nos. D771,607 (“the ’607 patent”), D775,620 (“the ’620 patent”), and D776,648 (“the ’648 patent”) (collectively the “Spigen Design Patents”), each of which claims a cellular phone case. Figures 3-5 of the ’607 patent are as shown below:

The ’620 patent disclaims certain elements shown in the ’607 patent, and Figures 3-5 of the ’620 patent are shown below:

Finally, the ’648 patent disclaims most of the elements present in the ’620 patent and the ’607 patent, Figures 3-5 of which are shown below:

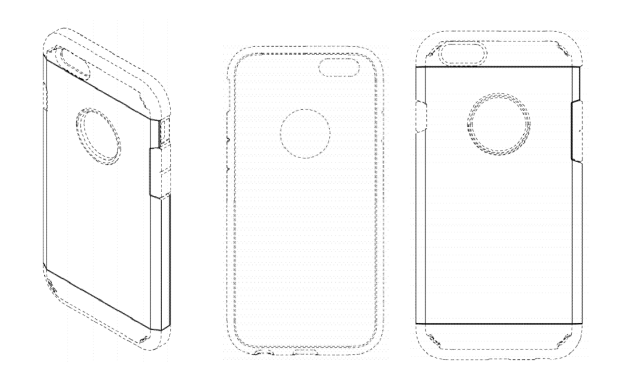

On February 13, 2017, Spigen sued Ultraproof for infringement of Spigen Design Patents in the United States District Court for the Central District of California. Ultraproof filed a motion for summary judgment of invalidity of Spigen Design Patents, arguing that the Spigen Design Patents were obvious as a matter of law in view of a primary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D729,218 (“the ’218 patent”) and a secondary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D772,209 (“the ’209 patent”). Spigen opposed the motion arguing that 1) the Spigen Design Patents were not rendered obvious by the primary and secondary reference as a matter of law; and 2) various underlying factual disputes precluded summary judgment. The district court held that as a matter of law, the Spigen Design Patents were obvious over the ’218 patent and the ’209 patent, and granted summary judgment of invalidity in favor of Ultraproof. Ultraproof then moved for attorneys’ fees, which the district court denied. Spigen appealed the district court’s obviousness determination, and Ultraproof cross-appealed the denial of attorneys’ fees.

On appeal, Spigen presented several arguments as to why the district court’s grant of summary judgment should be reversed. First, Spigen argued that there is a material factual dispute over whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference that precludes summary judgment. The CAFC agreed. The CAFC explained, citing Titan Tire Corp. v. Case New Holland, Inc., 566 F.3d 1372, 1380-81 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (quoting Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101 F.3d 100, 103 (Fed. Cir. 1996)) that the ultimate inquiry for obviousness “is whether the claimed design would have been obvious to a designer of ordinary skill who designs articles of the type involved,” which is a question of law based on underlying factual findings. Whether a prior art design qualifies as a “primary reference” is an underlying factual issue. The CAFC went on to explain that a “primary reference” is a single reference that creates “basically the same” visual impression, and for a design to be “basically the same,” the designs at issue cannot have “substantial differences in the[ir] overall visual appearance[s].” Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2012). A trial court must deny summary judgment if based on the evidence before the court, a reasonable jury could find in favor of the non-moving party. Here, the district court errored in finding that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” as the Spigen Design Patents despite there being “slight differences,” as a reasonable factfinder could find otherwise.

Spigen’s expert testified that the Spigen Design Patents and the ’218 patent are not “at all similar, let alone ‘basically the same.’” Spigen’s expert noted that the ’218 patent has the following features that are different from the Spigen Design Patents:

- unusually broad front and rear chamfers and side surfaces

- substantially wider surface

- lack of any outer shell-like feature or parting lines

- lack of an aperture on its rear side

- presence of small triangular elements illustrated on its chamfers

In contrast, Ultraproof argued that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” because of the presence of the following features:

- a generally rectangular appearance with rounded corners

- a prominent rear chamfer and front chamfer

- elongated buttons corresponding to the location of the buttons of the underlying phone

Ultraproof stated that the only differences were the “circular cutout in the upper third of the back surface and the horizontal parting lines on the back and side surfaces.”

Based on the competing evidence in the record, the CAFC found that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that the ’218 patent and the Spigen Design Patents are not basically the same. T

The CAFC determined that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference, and therefore, reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of invalidity and remanded the case for further proceedings.

Takeaway

When there is competing evidence in the record, the determination of whether a prior art reference creates “basically the same” visual impression, and therefore a proper primary reference, is a matter that cannot be decided at summary judgment.

WHEN FIGURES IN A DESIGN PATENT DO NOT CLEARLY SHOW AN ARTICLE OF MANUFACTURE FOR THE ORNAMENTAL DESIGN, THE TITLE AND CLAIM LANGUAGE CAN LIMIT THE SCOPE OF THE DESIGN PATENT

| October 7, 2019

Curver Luxembourg, SARL, v. Home Expressions Inc.

September 12, 2019

Chen (author), Hughes, and Stoll

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of a defendant’s motion to dismiss a complaint for failure to state a plausible claim of design patent infringement because when all of the drawings in a design patent at issue do not describe an article of manufacture for the ornamental design, the title, claim language, figure descriptions specifying an article of manufacture, which was amended during the prosecution of the patent based on the Examiner’s proposed amendment, can limit the scope of a design patent.

Details:

The ‘946 Patent

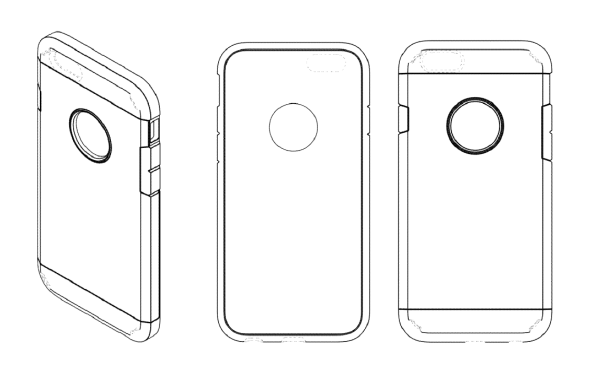

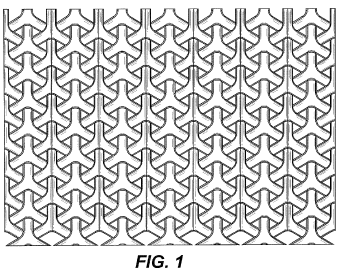

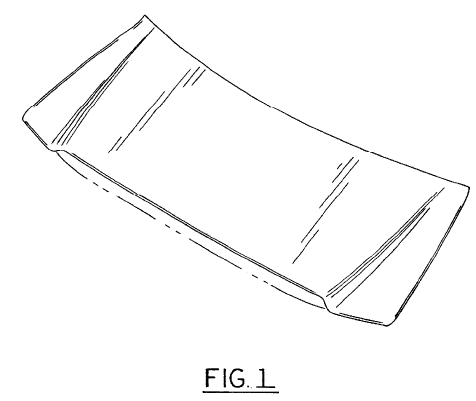

Curver Luxembourg, SARL (Curver) is the assignee of U.S. Design Patent No. D677,946 (‘946 patent) with a title “Pattern for a Chair” and claiming an “ornamental design for a pattern for a chair.” The ‘946 patent claims an overlapping “Y” design, as shown below. However, none of the figures illustrate a design being applied to a chair.

Prosecution

Curver originally applied for a patent directed to a pattern for “furniture,” and the original title was “FURNITURE (PART OF-).” The original claim recited a “design for a furniture part.”

However, during the prosecution, the Examiner allowed the claim but objected to the title because it was too vague to constitute an article of manufacture (in Ex Parte Quayle Action). The Examiner suggested amending the title to read “Pattern for a Chair,” and Curver accepted the Examiner’s suggestion by replacing the title with “Pattern for a Chair” and amending the claim term “furniture part” with “pattern for a chair.” Curver did not amend the figures to illustrate a chair. The Examiner accepted Curver’s amendments and allowed the application.

District Court

Home Expressions makes and sells baskets with a similar overlapping “Y” design disclosed in the ‘946 patent.

Curver sued Home Expressions accusing its basket products of infringing the ‘946 patent. Home Expressions filed a motion to discuss Curver’s complaint under Rule 12(b)(6) for failing to set forth a plausible claim of infringement.

Using a two-step analysis, the district court construed the scope of the ‘946 patent to be limited to the design pattern illustrated in the figures as applied to a chair and found that an ordinary observer would not purchase Home Expressions’s basket with “Y” design believing that the purchase was for “Y” design applied to a chair.

Therefore, the district court granted the Rule 12(b)(6) motion.

CAFC

The CAFC held that to define the scope of a design patent, the court traditionally focused on the figures illustrated in the patent. However, when all of the drawings fail to describe an article of manufacture for the ornamental design, the CAFC held that claim language specifying an article of manufacture can limit the scope of a design patent.

In addition, the CAFC uses §1.153(a) to held that “the design be tied to a particular article, but this regulation permits claim language, not just illustration along, to identify that article.”

The title of the design must designate the particular article. No description, other than a reference to the drawing, is ordinarily required. The claim shall be in formal terms to the ornamental design for the article (specifying name) as shown, or as shown and described.

The CAFC held that the prosecution history shows that Curver amended the title, claim, figure descriptions to recite “pattern for a chair” in order to satisfy the article of manufacture requirement necessary to secure its design patent. Therefore, the CAFC held that the scope of the ‘946 patent should be limited by those amendments.

Therefore, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s grant of Home Expressions’s motion to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a plausible claim of design patent infringement.

Takeaway:

- When figures in a design patent do not clearly show an article of manufacture for the ornamental design, the title and claim language can limit the scope of the design patent.

- Applicant should review the Examiner’s proposed amendments carefully before placing the application in condition for allowance.

- Applicant should be careful when crafting the title and claim language.

Tags: article of manufacture > claim > Design Patent > figure > patent infringement > title

“Built Tough”: Ford’s Design Patents Survive Creative Attacks by Accused Infringers

| August 21, 2019

Automotive Body Parts Association v. Ford Global Technologies, LLC

July 23, 2019

Before Hughes, Schall, and Stoll

Summary

The Federal Circuit is asked to decide two questions: what types of functionality invalidate a design patent, and whether the same rules of patent exhaustion and repair rights that apply to utility patents ought to also be applied to design patents. On the former, the Federal Circuit decides that “mechanical or utilitarian” functionality, rather than “aesthetic functionality”, invalidates a design patent. On the latter, however unique design patents are from utility patents, the Federal Circuit declines to apply the well-established rules of patent exhaustion and right to repairs differently between design and utility patents.

Details

Ford Motor Company introduced the F-150 pickup trucks in the 1970’s, and the trucks have become a mainstay of Ford’s lineup. The trucks’ popularity has endured, as the model is now in its thirteenth generation, with Ford claiming to have sold more than 1 million F-150 trucks in 2018.

Ford Global Technologies, LLC (“Ford”) is a subsidiary of Ford Motor Company, and manages the parent company’s intellectual property. Ford’s large patent portfolio includes numerous design patents covering different design elements of Ford vehicles. Among those design patents are U.S. Design Patent Nos. D489,299 and D501,685.

The D’299 patent is directed to an “exterior vehicle hood” having the following design:

The D’685 patent is directed to a “vehicle head lamp” having the following design:

The patented designs are found on the eleventh generation F-150 trucks, which were in production from 2004 to 2008:

Automotive Body Parts Association (“Automotive Body”) is an association of companies that distribute automotive body parts. The member companies serve predominantly the collision repair industry, selling replacement auto parts to collision repair shops or directly to vehicle owners.

Ford began asserting the D’299 and D’685 patents against Automotive Body in 2005, when Ford initiated a patent infringement action in the International Trade Commission. The ITC action was ultimately settled, followed by a few years of relative quiet until 2013, when tension grew after a member of Automotive Body began selling replacement parts covered by Ford’s two design patents.

In 2013, Automotive Body, together with the member company, initiated a declaratory judgment action in a district court, seeking to have the D’299 and D’685 patents declared invalid, or if valid, unenforceable. Automotive Body moved the district court for summary judgment of invalidity and unenforceability, but was denied. Automotive Body’s appeal of that denial of summary judgment leads us to this decision by the Federal Circuit.

Automotive Body’s arguments on appeal mirror those made in the district court.

- Invalidity

Automotive Body makes two main invalidity arguments. First, the designs of Ford’s two patents are “dictated by function”, and second, the two designs are not a “matter of concern”.

The “dictated by function” argument involves a basic design patent concept: if an article has to be designed a certain way for the article to function, then the design cannot be the subject of a design patent.

Design patents protect only “new, original and ornamental design[s] for an article of manufacture”. 35 U.S.C. 171(a). To be “ornamental”, a particular design must not be essential to the use of the article.

Automotive Body argues, rather creatively, that the designs of Ford’s headlamp and hood are functionally dictated not only by the physical fit on a F-150 truck, but also by the aesthetics of the surrounding body parts. Automotive Body’s position is that these commercial requirements for aesthetic continuity, driven by customer preferences, render Ford’s designs functional.

The Federal Circuit disagrees:

We hold that, even in this context of a consumer preference for a particular design to match other parts of a whole, the aesthetic appeal of a design to consumers is inadequate to render that design functional…If customers prefer the “peculiar or distinctive appearance” of Ford’s designs over that of other designs that perform the same mechanical or utilitarian functions, that is exactly the type of market advantage “manifestly contemplate[d]” by Congress in the laws authorizing design patents.

In other words, functionality that invalidates a design should be “mechanical or utilitarian”, and not aesthetical.

Particularly damaging to Automotive Body’s argument is Ford’s abundant evidence of “performance parts”, that is, alternative headlamp and hood designs that would also fit the F-150 trucks. As the Federal Circuit explains, “the existence of ‘several ways to achieve the function of an article of manufacture,’ though not dispositive, increases the likelihood that a design serves a primarily ornamental purpose.”

To bolster its functionality argument, Automotive Body attempts to borrow the doctrine of “aesthetic functionality” from trademark law.

Under that doctrine, trademark protection is unavailable to features that serve an aesthetic function that is independent and distinct from the function of source identification. For example, “John Deere green”, the color, may invoke an immediate association with John Deere, the brand, but the color itself also serves the significant nontrademark function of color-matching many farm equipment. As such, the color is not entitled to trademark protection.[1]

The Federal Circuit quickly disposes of Automotive Body’s “aesthetic functionality” argument, finding that the doctrine rooted in trademark law does not apply to patent law. The competitive considerations driving the “aesthetic functionality” doctrine of trademark law do not apply to the anticompetitive effects of design patents.

Automotive Body’s second invalidity argument is that the designs of Ford’s two patents are not a “matter of concern”.

The “matter of concern” argument involves the straightforward concept that, if no one cares about a particular design, then that design is not deserving of patent protection. Automotive Body argues that Ford’s patented headlamp and hood designs are not a “matter of concern”, because an F-150 owner in need of a replacement headlamp or hood would assess the replacement part simply for their aesthetic compatibility with the truck.

The Federal Circuit finds two faults with Automotive Body’s arguments. First, that an F-150 owner would assess the aesthetic of a headlamp or hood design means that, by definition, the designs are a matter of concern. Second, Automotive Body errs in temporally limiting the “matter of concern” inquiry to when a consumer is purchasing a replacement part. The proper inquiry is “whether at some point in the life of the article an occasion (or occasions) arises when the appearance of the article becomes a ‘matter of concern’”.

- Unenforceability

Automotive Body’s unenforceability arguments are also two-fold.

First, Automotive Body argues that under the doctrine of patent exhaustion, the authorized sale of an F-150 truck exhausts all design patents embodied in the truck. This exhaustion therefore permits the use of Ford’s designs on replacement parts intended for use with the truck.

The Federal Circuit disagrees that the doctrine of patent exhaustion should be so broadly applied.

The doctrine of patent exhaustion is triggered only if the sale is authorized, and conveys only with the article sold. Since Ford has not authorized Automotive Body’s sales of replacement headlamps and hood, and Automotive Body is not a purchaser of Ford’s F-150 trucks, the Federal Circuit easily concludes that Automotive Body cannot rely on patent exhaustion as a defense.

Automotive Body’s second argument is that an authorized sale of the F-150 truck also conveys to the owner the right to repair, so that the owner of the F-150 truck would be permitted to replace the headlamps or hood on the truck.

Here also, the Federal Circuit disagrees with Automotive Body’s broad application of the right to repair.

The right to repair allows an owner to repair the patented headlamps or hood on the truck, but does not allow the owner to make new copies of the patented designs.

A common premise of Automotive Body’s unenforceability arguments is their broad interpretation of the term “article of manufacture” as used in the statute. From Automotive Body’s perspective, the term includes not only the patented component, but also the larger product incorporating that component. By this interpretation, the sale of either the patented headlamps or hood, or the truck containing the patented headlamps or hood would totally exhaust Ford’s rights in the design patents.

The Federal Circuit rejects Automotive Body’s broad interpretation:

In our view, the breadth of the term “article of manufacture” simply means that Ford could properly have claimed its designs as applied to the entire F-150 or as applied to the hood and headlamp… Unfortunately for ABPA, Ford did not do so; the designs for Ford’s hood and headlamp are covered by distinct patents, and to make and use those designs without Ford’s authorization is to infringe.

Had Ford’s design patents covered the whole F-150 truck, the sale of the truck would have exhausted Ford’s rights in those patents. But, as it were, Ford’s patents cover only the designs of the headlamps and the hood, and not the design for the truck as a whole. As such, while the authorized sale of an F-150 truck permits the owner to use and repair the headlamps and the hood, the sale leaves untouched Ford’s ability to prevent the owner from making new copies of those designs.

It is not uncommon for aftermarket suppliers, especially those who supply parts intended to restore a vehicle to its original condition and aesthetics, to promise identity or near identity between its products and the OEM parts. This promise, however, would effectively be an admission that the products infringe any design patents covering the part. In this respect, this Federal Circuit decision may signal a tough road ahead for aftermarket suppliers.

Takeaway

- Use design patents not only to protect a product as a whole, but also to protect the smallest sellable component of the product.

[1] Interestingly, a district court recently determined that trademark protection extended to the combination of “John Deere green” and “John Deere yellow” as a color scheme.

Design patent claim must not be construed eliminating functional elements.

| May 11, 2016

Sport Dimension v. The Coleman Company

April 19, 2016

Before Moore, Hughes and Stoll. Opinion by Stoll.

Summary:

The district court interpreted the claim of a design patent for a personal flotation device eliminating armbands and side torso tapering entirely from the claim because these are functional. CAFC rejected the claim construction vacating the judgment of non-infringement and remanded. CAFC ruled that even though the elements served a functional purpose, the construction improperly converted the claim scope of the design patent from one that covered the overall ornamentation to one that covered individual elements.

地裁は、救命胴衣に関するデザイン特許のクレームの解釈で、アームバンドと、次第に細くなる胴体側部をクレームから除外して解釈した。CAFCは、クレーム解釈及び非侵害の判断を破棄し、地裁に差戻した。CAFCはそれらの要素が機能的目的のものであっても、地裁の解釈は、全体的な装飾的観点をカバーするデザイン特許のクレーム範囲を、個々の要素をカバーするものに不当に変更するものであるとした。

In a design patent infringement case, 35 U.S.C. §289 authorizes the award of total profit from the article of manufacture bearing the patented design

| May 27, 2015

Apple Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. et al.

May 18, 2015

Before: Prost, O’Malley and Chen. Opinion by Prost.

Summary

The CAFC affirmed the jury’s verdict on the design patent infringements and the validity of utility patent claims, and the damages awarded for these infringements appealed by Samsung. However, CAFC reversed the jury’s findings that the asserted trade dresses are protectable. Regarding the design patent infringement issue, Samsung proposed that functional aspects of the design patents should be “ignored” in their entirety in a design patent infringement analysis, the CAFC disagreed. Moreover, the CAFC found that the district court did not err by allowing jury to award damages based on Samsung’s entire profits on its infringing smartphones.

サムスン社は、控訴審において、意匠特許の機能的部分は意匠特許侵害の分析において無視されるべきであると主張した。CAFCは、機能的部分の装飾的な特徴は意匠特許によりカバーされるため、意匠特許侵害の分析において機能的部分を無視すべきというサムスン社の主張には同意しなかった。また、サムスン社は、意匠特許侵害の損害賠償は、侵害商品の全体としての利益(entire profit)に基づいて計算されるべきでないと主張したものの、特許法第289条は、意匠特許侵害の損害賠償を侵害商品の全体としての利益(entire profit)に基づいて計算することを可能としているため、CAFCはこの主張にも同意しなかった。

“Ordinary Designer” Standard Should Be Used in Design Patent Obviousness Analysis

| October 24, 2013

High Point Design LLC, et al. v. Buyer’s Direct, Inc.

September 11, 2013

Panel: O’Malley, Schall, and Wallach. Opinion by Schall

Summary

This case addresses obviousness and functionality analysis for design patents. The CAFC stated that the obviousness of a design patent must be analyzed from the perception of a designer of ordinary skill in the field to which the design pertains. With regards to functionality, a design that can perform functions can be protected under design patent so long as the claimed design is “primarily ornamental” and not “primarily functional.”

意匠特許の自明性を判断する場合には、その意匠の分野の当業者の観点から分析を行うことが必要とされる。また、機能的な要素を有する意匠でも、その意匠が主として機能的ではなく、主として装飾的であれば、意匠特許の対象となる。

Tags: Design Patent > Functionality > obviousness