BREATHE EASIER, THE CAFC PROVIDES GUIDANCE ON CONSTRUING THE CLAIMED CONCENTRATION OF A STABILIZER IN PATENTS FOR AN ASTHMA DRUG

| February 25, 2022

AstraZeneca v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals

Decided December 8, 2021

Taranto, Hughes, and Stoll. Opinion by Stoll. Dissent by Taranto

Summary:

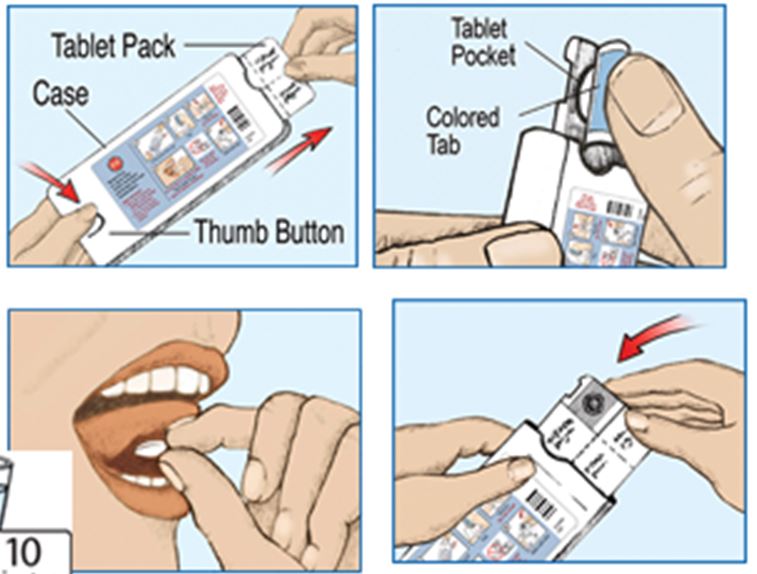

AstraZeneca sued Mylan for infringement of its patents covering Symbicort pressurized metered-dose inhaler (pMDI) which is used for treating asthma. At issue in this case is how to construe the limitation “PVP K25 is present at a concentration of 0.001% w/w.” The district court construed the concentration using the ordinary standard scientific convention using only one significant figure to encompass the range from 0.0005% to 0.0014%. Based on this construction, Mylan stipulated to infringement. The district court then held a trial on validity and upheld the validity of the asserted claims. The CAFC affirmed the district court’s judgment of validity. But the CAFC disagreed with the construction of the concentration limitation. The CAFC held that the construction of the term should be narrower than the range provided by the ordinary meaning due to disclosures in the specification and arguments and amendments in the prosecution history. The CAFC construed the noted concentration of 0.001% to include the narrower range of 0.00095% to 0.00104%. Thus, the CAFC vacated the judgment of infringement and remanded for further proceedings on infringement.

Details:

The patents at issue in this case are U.S. Patent Nos. 7,759,328; 8,143,239; and 8,575,137 which cover the asthma inhaler Symbicort pMDI. A pMDI inhaler uses a propellant gas that is in liquid form under pressure in the pMDI device. When the inhaler is activated, the propellant causes the gas to come out as a spray making it easier to deliver the medication to the lower lungs. The representative claim is provided:

13. A pharmaceutical composition comprising

formoterol fumarate dihydrate, budesonide, HFA227, PVP K25, and PEG-1000,

wherein the formoterol fumarate dihydrate is present at a concentration of 0.09 mg/ml,

the budesonide is present at a concentration of 2 mg/ml,

the PVP K25 is present at a concentration of 0.001% w/w, and

the PEG-1000 is present at a concentration of 0.3% w/w.

Mylan appealed the district court’s stipulated judgment of infringement asserting that the district court erred in the construction of the concentration of PVP K25 of 0.001%. Mylan also appealed the district court judgement of nonobviousness.

The CAFC stated that as a matter of standard scientific convention, the noted concentration of 0.001% being expressed with only one significant digit would ordinarily encompass a range from 0.0005% to 0.0014%. AstraZeneca argued that this ordinary meaning controls absent lexicography or disclaimer. However, the CAFC stated that this is an acontextual construction that does not consider disclosures in the specification and arguments/amendments in the prosecution history. The CAFC stated that “[c]onsistent with Phillips, therefore, we must read the claims in view of both the written description and prosecution history.”

The CAFC stated that the testing evidence in the specification and prosecution history demonstrates that minor differences as small as ten thousandths of a percentage (four decimal places) in the concentration of PVP impact stability. The specification repeatedly describes formulations containing 0.001% PVP as providing the best suspension stability. This is also demonstrated in the data provided in the specification. The data includes formulations including PVP at concentrations of 0.0001%, 0.0005%, 0.001%, 0.01%, 0.03%, and 0.05%. The results show that the formulation containing 0.001% PVP was the most stable and that the formulation containing 0.0005% was one of the least stable formulations. The CAFC concluded that this data shows that PVP concentration of 0.001% is more stable than formulations with slight differences in PVP concentration (e.g., a concentration of 0.0005%, and that differences down to the ten-thousandth of a percentage (fourth decimal place) matters for stability.

In the prosecution history, the Applicant amended the claims to change ranges of the concentration to recite the exact concentration of PVP to 0.001% without using the qualifier “about,” and emphasized that 0.001% was critical to stability. The CAFC also stated that Applicant knew how to claim ranges and describe numbers with approximation using the term “about,” but the Applicant chose to claim the exact value. The CAFC concluded that this supports construing 0.001% narrowly, but that there should be some room for experimental error in the PVP concentration. The CAFC stated that the margin of error that is best supported by the intrinsic record is variations in the PVP concentration at the fourth decimal place (0.000095% to 0.000104%).

AstraZeneca argued that Mylan’s proposed construction is an attempt to limit the scope of the claims to the preferred embodiment. However, the CAFC stated that AstraZeneca’s proposed construction would read on two distinct formulations described in the specification (0.0005% PVP and 0.001% PVP), but the Applicant chose to claim only one of these formulations. The CAFC also stated that Applicant cancelled claims that included the 0.0005% PVP concentration and that this provides evidence that the formulations containing 0.0005% PVP are not within the scope of an asserted claim.

Regarding the nonobviousness determination by the district court, Mylan argued that the district court erred in finding that the prior art reference Rogueda taught away from the claimed invention. The CAFC citing Meiresonne v. Google, Inc., 849 F.3d 1379 (Fed Cir. 2017), stated that “a prior art reference is said to teach away from the claimed invention if a skilled artisan ‘upon reading the reference, would be discouraged from following the path set out in the reference, or would be led in a direction divergent from the path that was taken’ in the claim.”

The Rogueda reference included control formulations to compare with its novel formulations. Mylan relied on some of the control formulations as rendering the claims obvious. Rogueda disclosed that the novel formulations provided a “drastic” reduction in the amount of drug adhesion compared to the controls.

Mylan, citing Meiresonne, argued that the court’s precedent regarding “teaching away” is that a reference “that merely expresses a general preference for an alternative invention but does not criticize, discredit, or otherwise discourage investigation into the claimed invention does not teach away.” Mylan argued that Rogueda merely expresses a preference for the novel formulations over the control formulations citing a statement in the district court opinion that “Rogueda did not necessarily disparage the formulations in Controls 3 and 9.” However, AstraZeneca provided expert testimony stating that a skilled artisan looking at the adhesion results in Rogueda would conclude that the control formulations “were not suitable” and “clearly don’t work.” The district court credited the expert testimony that a skilled artisan would have known that the control formulations were unsuitable, and thus, discouraging investigation into these formulations, and concluded that Rogueda teaches away and does not render the claims obvious. The CAFC stated that there was no clear error in the district court’s determination and affirmed the validity of the claims.

Dissent

Judge Taranto dissented from the claim construction opinion. Judge Taranto stated that 0.001% should be construed to have its significant-figure meaning of 0.0005% to 0.0014% with the possibility of shrinking the lower end of the range to exclude the overlap area between the significant-figure interval of 0.001% (0.0005% to 0.0014%) and the significant-figure interval of 0.0005% (00045% to 0.00054%). Thus, if this exclusion is applied, the range would be 0.00055% to 0.0014%.

Judge Taranto takes the position that nothing in the specification or prosecution history warrants departing from the ordinary meaning. Judge Taranto pointed out that the specification, when referring to the formulations that were tested, states that several of the formulations were “considered excellent” and that the formulation with 0.001% PVP “gave the best suspension ability overall.” In the prosecution history, the Examiner stated the need for the Applicant to show criticality by showing unexpected results of a 0.001% concentration level compared to concentration levels “slightly greater or less” than 0.001% PVP. But it is unclear if the Examiner meant to include 0.0005% and other tested concentration levels tested within the meaning of “slightly greater or less.” The Examiner’s statement about criticality does not exclude 0.0005%.

Judge Taranto also stated that changing “0.001%” having one significant figure to “0.0010%” having two significant figures (as proposed by Mylan and adopted by the majority) requires rewriting the claim term, and that this rewriting is counter to the specification and prosecution history. The specification and prosecution history uniformly used only one significant figure when referring to PVP concentration. Just because four decimal places were used for some PVP concentrations does not mean that all concentration values should be read to express a degree of precision to four decimal places. The specification uses four decimal places to refer to the absolute concentration level in examples where this is unavoidable such as for 0.0001% and 0.0005%. However, absolute levels and degrees of precision are distinct.

Judge Taranto also addressed the fact that the range implied by 0.001% overlaps the range implied by 0.0005%. Judge Taranto stated that the overlap does not support adding an extra significant digit. Judge Taranto stated that “the most this overlap could possibly support would be an exclusion of the small range with the one significant-figure interval for which there is overlap resulting in the range of 0.00055% to 0.0014%. However, Judge Taranto pointed out that Mylan’s product is still within this narrower range, and thus, it is not necessary to decide whether the overlap-area exclusion is justified as a claim construction.

Comments

The majority appears to have been swayed by the fact that a formulation within the range of the ordinary meaning of the claimed concentration provided significantly different results. What is not clear is whether these different results, while not the best, could still be considered good. Judge Taranto pointed out that the specification stated that several of the tested formulations were considered excellent while the 0.001% was the best. When drafting and prosecuting patent applications, you need to be aware that your experimental data and amendments to the claims can be used to narrow the range afforded by the ordinary meaning of a certain value.

With regard to arguing non-obviousness due to a teaching away in the prior art, expert testimony can be critical and should be used to support your argument whether you are defending the validity of a patent or trying to invalidate.

Prosecution history disclaimer dooms infringement case for patentee

| November 22, 2021

Traxcell Technologies, LLC v. Nokia Solutions and Networks

Decided on October 12, 2021

Prost, O’Malley, and Stoll (opinion by Prost)

Summary

Patentee’s arguments during prosecution distinguishing the claimed invention over prior art were found to be clear and unmistakable disclaimer of certain meanings of the disputed claim terms. The prosecution history disclaimer resulted in claim constructions that favored the accused infringer and compelled a determination of non-infringement.

Details

Traxcell Technologies LLC specializes in navigation technologies. The company was founded by Mark Reed, who is also the sole inventor behind U.S. Patent Nos. 8,977,284, 9,510,320, and 9,642,024 that Traxcell accused Nokia of infringing.

The 284, 320, and 024 patents are directly related to each other as grandparent, parent, and child, respectively. The three patents are concerned with self-optimizing wireless network technology. Specifically, the patents claim systems and methods for measuring the performance and location of a wireless device (for example, a phone), in order to make “corrective actions” to or tune a wireless network to improve communications between the wireless device and the network.

The asserted claims from the three patents require a “first computer” (or in some of the asserted claims, simply “computer”) that is configured to perform several functions related to the “location” of a mobile wireless device.

Central to the parties’ dispute was the proper constructions of “first computer” and “location”.

Nokia’s accused geolocation system was undisputedly a self-optimizing network product. Nokia’s system performed similar functions as those claimed in the asserted computers, but across multiple computers. Nokia’s system also collected performance information for mobile wireless devices located within 50-meter-by-50-meter grids.

To avoid infringement, Nokia argued that the claimed “first computer” required a single computer performing the claimed functions, and that the claimed “location” required more than the use of a grid.

On the other hand, wanting to capture Nokia’s products, Traxcell argued that the claimed “first computer” encompassed embodiments in which the claimed functions were spread among multiple computers, and that the claimed “location” plainly included a grid-based location.

Unfortunately for Traxcell, their arguments did not stand a chance against the prosecution histories of the asserted patents.

The doctrine of prosecution history disclaimer “preclud[es] patentees from recapturing through claim interpretation specific meanings disclaimed during prosecution”. Omega Eng’g, Inc. v. Raytek Corp., 334 F.3d 1314, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2003). “Prosecution disclaimer can arise from both claim amendments and arguments”. SpeedTrack, Inc. v. Amazon.com, 998 F.3d 1373, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2021). “An applicant’s argument that a prior art reference is distinguishable on a particular ground can serve as a disclaimer of claim scope even if the applicant distinguishes the reference on other grounds as well”. Id. at 1380. For there to be disclaimer, the patentee must have “clearly and unmistakably” disavowed a certain meaning of the claim.

Of the three asserted patents, the 284 patent had the most protracted prosecution, with six rounds of rejections. And it was the prosecution history of the 284 patent that provided the fodder for the district court’s claim constructions. Incidentally, the 284 patent was also the only one of the three asserted patents prosecuted by the inventor, Mark Reed, himself.

During claim construction, the district court construed the terms “first computer” and “computer” to mean a single computer that could performed the various claimed functions.

The district court first looked to the plain language of the claims. The claim language recites “a first computer” or “a computer” that performs a function, and then recites that “the first computer” or “the computer” performs several additional functions. The district court determined that the claims plainly tied the claimed functions to a single computer, and that “it would defy the concept of antecedent basis” for the claims to refer back to “the first computer” or “the computer”, if the corresponding tasks were actually performed by a different computer.

The intrinsic evidence that convinced the district court of its claim construction was, however, the prosecution history of the 284 patent.

During prosecution, in a 67-page response, Mr. Reed argued explicitly and at length, in a section titled “Single computer needed in Reed et al. [i.e., the pending application] v. additional software needed in Andersson et al. [i.e., the prior art]”, that the claimed invention requiring just one computer distinguished over the prior art system using multiple computers. The district court quoted extensively from this response as intrinsic evidence supporting its claim construction.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s claim construction, quoting still more passages from the same response as evidence that the patentee “clearly and unmistakably disclaimed the use of multiple computers”.

Next, the district court addressed the term “location”. The district court construed the term to mean a “location that is not merely a position in a grid pattern”.

Here, the district court’s claim construction relied almost exclusively on arguments that Reed made during prosecution of the 284 patent. Referring again to the same 67-page response, the district court noted that Mr. Reed explicitly argued, in a section titled “Grid pattern not required in Reed et al. v. grid pattern required in Steer et al.”, that the claimed invention distinguished over the prior art because the claimed invention operated without the limitation of a grid pattern, and that the absence of a grid pattern permitted finer tuning of the network system.

And again, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s claim construction, finding that “the disclaimer here was clear and unmistakable”.

The claim constructions favored Nokia’s non-infringement arguments that its system lacked the single-computer, non-grid-pattern-based-location limitations of the asserted claims. Accordingly, the district court found, and the Federal Circuit affirmed, that Nokia’s system did not infringe the 284, 320, and 024 patents.

Traxcell made an interesting argument on appeal—specifically, the disclaimer found by the district court was too broad and a narrower disclaimer would have been enough to overcome the prior art. Traxcell seemed to be borrowing from the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel. Under that doctrine, arguments or amendments made during prosecution to obtain allowance of a patent creates prosecution history estoppel that limits the range of equivalents available under the doctrine of equivalents.

However, the Federal Circuit was unsympathetic to Traxcell’s argument, explaining that Traxcell was held “to the actual arguments made, not the arguments that could have been made”. The Federal Circuit also noted that “it frequently happens that patentees surrender more…than may have been absolutely necessary to avoid particular prior art”.

Mr. Reed’s somewhat unsophisticated prosecution of the 284 patent was in sharp contrast to the prosecution of the related 320 and 024 patents, which were handled by a patent attorney. The prosecution histories of the 320 and 024 patents said very little about the cited prior art, even less about the claimed invention. In addition, whereas Mr. Reed editorialized on various claimed features during prosecution of the 284 patent, the prosecution histories of the 320 and 024 patents rarely even paraphrased the claims.

Takeaways

- Avoid gratuitous remarks that define or characterize the claimed invention or the prior art during prosecution. Quote the claim language directly and avoid paraphrasing the claim language, as the paraphrases risk being construed later as a narrowing characterization of the claimed invention.

- Avoid claim amendments that are not necessary to distinguish over the prior art.

- The prosecution history of a patent can affect the construction of claims in other patents in the same family, even when the claim language is not identical. Be mindful about how arguments and/or amendments made in one application may be used against other related applications.

PATENT CLAIMS CANNOT BE CONSTRUED ONE WAY FOR ELIGIBILITY AND ANOTHER WAY FOR INFRINGEMENT

| September 17, 2021

Data Engine Technologies LLC v. Google LLC

Decided on August 26, 2021

Reyna, Hughes, Stoll. Opinion by Stoll.

Summary:

This case is a second appeal to the CAFC. In the first appeal, the CAFC reversed the district court and determined that certain claims of patents owned by Data Engine Technologies LLC (DET) directed to spreadsheet technologies are patent eligible subject matter. In arguing patent eligible subject matter, DET emphasized the claimed improvement as being unique to three-dimensional spreadsheets. On remand, the district court construed the preamble of the claims having the phrase “three-dimensional spreadsheet” as limiting, and based on this claim construction, granted Google’s motion for summary judgment of noninfringement. In this appeal, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s determination that the preamble of the claims is limiting and that the district court’s construction of the term “three-dimensional spreadsheet” is correct. Thus, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s summary judgment of noninfringement.

Details:

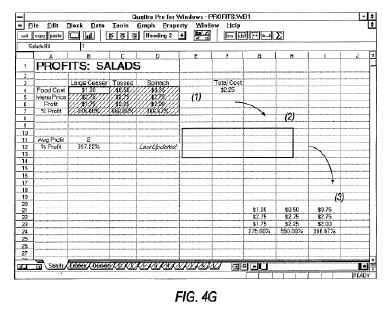

DET’s patents at issue in this case are U.S. Patent Nos. 5,590,259; 5,784,545; and 6,282,551 directed to systems and methods for displaying and navigating three-dimensional electronic spreadsheets. They describe providing “an electronic spreadsheet system including a notebook interface having a plurality of notebook pages, each of which contains a spread of information cells, or other desired page type.” Figs. 2A and 2D of the ‘259 patent are shown below. Fig. 2A shows a spreadsheet page having notebook tabs along the bottom edge. Fig. 2D shows just the notebook tabs of the spreadsheet.

Claim 12 of the ‘259 patent is a representative claim and is provided below:

12. In an electronic spreadsheet system for storing and manipulating information, a computer-implemented method of representing a three-dimensional spreadsheet on a screen display, the method comprising:

displaying on said screen display a first spreadsheet page from a plurality of spreadsheet pages, each of said spreadsheet pages comprising an array of information cells arranged in row and column format, at least some of said information cells storing user-supplied information and formulas operative on said user-supplied information, each of said information cells being uniquely identified by a spreadsheet page identifier, a column identifier, and a row identifier;

while displaying said first spreadsheet page, displaying a row of spreadsheet page identifiers along one side of said first spreadsheet page, each said spreadsheet page identifier being displayed as an image of a notebook tab on said screen display and indicating a single respective spreadsheet page, wherein at least one spreadsheet page identifier of said displayed row of spreadsheet page identifiers comprises at least one user-settable identifying character;

receiving user input for requesting display of a second spreadsheet page in response to selection with an input device of a spreadsheet page identifier for said second spreadsheet page;

in response to said receiving user input step, displaying said second spreadsheet page on said screen display in a manner so as to obscure said first spreadsheet page from display while continuing to display at least a portion of said row of spreadsheet page identifiers; and

receiving user input for entering a formula in a cell on said second spreadsheet page, said formula including a cell reference to a particular cell on another of said spreadsheet pages having a particular spreadsheet page identifier comprising at least one user-supplied identifying character, said cell reference comprising said at least one user-supplied identifying character for said particular spreadsheet page identifier together with said column identifier and said row identifier for said particular cell.

In the first appeal regarding patent eligibility, DET argued that a key aspect of the patents “was to improve the user interface by reimagining the three-dimensional electronic spreadsheet using a notebook metaphor.” DET argued that claim 12 is directed to patent-eligible subject matter because it is to a concept that solves “a problem that is unique to not only computer spreadsheet applications …., but specifically three-dimensional electronic spreadsheets.” In that appeal, the CAFC agreed that claim 12 is to patent eligible subject matter and remanded to the district court.

On remand, during claim construction, a dispute arose over whether the preamble is a limitation of the claims requiring construction, and if so, what is the proper construction of the term. The district court determined that the preamble is limiting and determined that the term “three-dimensional spreadsheet” means a “spreadsheet that defines a mathematical relation among cells on different spreadsheet pages, such that cells are arranged in a 3-D grid.” Based on this interpretation, Google moved for summary judgment of noninfringement because Google Sheets is not a “three-dimensional spreadsheet” as required by the claims. The district court granted the motion because “Google Sheets does not allow a user to define the relative position of cells in all three dimensions and is, therefore, incapable of infringing” the claims.

In this appeal, DET argued that the preamble term “three-dimensional spreadsheet” is not limiting and thus does not have patentable weight. The CAFC disagreed stating that a patentee cannot rely on language found in the preamble of the claim to successfully argue patent eligible subject matter, and then later assert that the preamble term has no patentable weight for purposes of showing infringement. The CAFC stated that “[w]e have repeatedly rejected efforts to twist claims, ‘like a nose of wax,’ in ‘one way to avoid [invalidity] and another to find infringement.’” In citing an analogous case, the CAFC stated that it cannot be argued that the preamble has no weight when the preamble was used in prosecution to distinguish prior art. In re Cruciferous Sprout Litig., 301 F.3d 1343, 1347–48 (Fed. Cir. 2002). The CAFC concluded that because DET emphasized the preamble term to support patent eligibility, the preamble term “three-dimensional spreadsheet” is limiting.

DET next argued that the construction of “three-dimensional spreadsheet” does not require “a mathematical relation among cells on different spreadsheet pages” as required by the district court’s construction. The CAFC stated that the claim language and the specification do not provide guidance on whether the mathematical relation is required. However, the CAFC looked to the prosecution history. To overcome a rejection based on a prior art reference, the applicant provided a definition of a “true” three-dimensional spreadsheet and stated that the prior art does not provide a true 3D spreadsheet. According to the applicant, a “true” three-dimensional spreadsheet “defines a mathematical relation among cells on the different pages so that operations such as grouping pages and establishing 3D ranges have meaning.” Based on this definition provided in the prosecution history, the CAFC stated that the district court properly interpreted “three-dimensional spreadsheet” as requiring a mathematical relation among cells on different spreadsheet pages.

DET argued that the definition provided in the prosecution history does not rise to the level of “clear and unmistakable” disclaimer when read in context. Specifically, DET stated in the same remarks that the prior art reference is a three-dimensional spreadsheet, and thus, could not have been distinguishing the prior art based on the three-dimensional spreadsheet feature. DET stated that they distinguished the prior art on the basis that the prior art linked different user-named spreadsheet files and that this is not the same as the claimed “user-named pages in a 3D spreadsheet.” Thus, DET argued that the statements defining a “true” 3D spreadsheet are irrelevant. However, the CAFC stated that they have held patentees to distinguishing statements made during prosecution even if they said more than needed to overcome a prior art rejection citing Saffran v. Johnson & Johnson, 712 F.3d 549, 559 (Fed. Cir. 2013). Thus, the CAFC concluded that even if the specific definition of a “true” 3D spreadsheet was not necessary to overcome the rejection, the express definition was provided, and DET cannot escape the effect of this statement made to the USPTO by suggesting that the statement was not needed to overcome the rejection. The CAFC affirmed the district court’s claim construction and its summary judgment of noninfringement.

Comments

In litigation, you will not be able to vary the construction of claims one way for validity and another way for infringement. Also, if you rely on features in the preamble of a claim for validity, the preamble will be considered as limiting and having patentable weight for infringement purposes.

Another key point from this case is that during prosecution of a patent application, you should say as little as possible to distinguish the prior art. Distinguishing statements in the prosecution history, even if not necessary to overcome the prior art, can be used to limit your claims.

Claim construction of a non-functional term in an apparatus claim; proof of vitiation against infringement under the doctrine of equivalents

| March 29, 2021

Edgewell Personal Care Brands, LLC v. Munchkin, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021) (Case No. 2020-1203)

March 9, 2021

Newman, Moore, and Hughes. Court opinion by Moore

Summary

On appeals from the district court for summary judgment of noninfringement of two patents, both directed to a cassette to be installed when a diaper pail system is in use, the Federal Circuit unanimously vacated the summary judgment of noninfringement of one patent because of erroneous claim construction, with caution that it is usually improper to construe non-functional claim terms in apparatus claims in a way that makes infringement or validity turn on the way an apparatus is later put to use. Furthermore, the Federal Circuit unanimously reversed the summary judgment of noninfringement of the other patent under the doctrine of equivalents because of erroneous application of the vitiation theory in the context of summary judgment, with caution that courts should be cautious not to shortcut the inquiry for infringement under the doctrine of equivalents by identifying a ‘binary’ choice in which an element is either present or ‘not present.’”

Details

I. Background

(i) The Patents in Dispute

U.S. Patent Nos. 8,899,420 (“the ’420 patent”) and 6,974,029 (“the ’029 patent”) are directed to a cassette to be installed when a diaper pail system is in use.

The ’420 patent is directed to a cassette with a “clearance” located in a bottom portion of the cassette. Claim 1 is the representative of the ’420 patent, which recites:

1. A cassette for packing at least one disposable object, comprising: an annular receptacle including an annular wall delimiting a central opening of the annular receptacle, and a volume configured to receive an elongated tube of flexible material radially outward of the annular wall; a length of the elongated tube of flexible material disposed in an accumulated condition in the volume of the annular receptacle; and an annular opening at an upper end of the cassette for dispensing the elongated tube such that the elongated tube extends through the central opening of the annular receptacle to receive disposable objects in an end of the elongated tube,

wherein the annular receptacle includes a clearance in a bottom portion of the central opening, … (emphasis added).

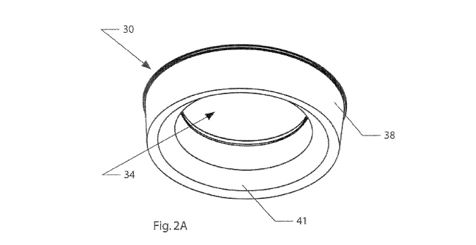

Fig. 2A of the ’420 patent, reproduced below, illustrates a bottom perspective view of a cassette 30 to be used with an apparatus 10 (not shown in the figure) for packaging disposable objects (34: a central opening; 38: a bottom annular receptacle; a chamfer clearance 41).

The ’029 patent is directed to a cassette with a cover extending over pleated tubing housed therein. Claim 1 is the representative of the ’029 patent, which recites:

1. A cassette for use in dispensing a pleated tubing comprising:

an annular body having a generally U shaped cross-section defined by an inner wall, an outer wall and a bottom wall joining a lower part of said inner and outer walls, said walls defining a housing in which the pleated tubing is packed in layered form;

an annular cover extending over said housing; said cover having an inner portion extending downwardly and engaging an upper part of said inner wall of said body and a top portion extending over said housing; said top portion including a tear-off outwardly projecting section having an outer edge engaging an upper part of said outer wall of said annular body; said tear-off section, when torn-off, leaving a peripheral gap to allow access and passage of said tubing therebetween; said downwardly projecting inner portion having an inclined annular area defining a funnel to assist in sliding said tubing when pulled through a central core defined by said inner wall of said body; and … (emphasis added).

(ii) The District Court

Edgewell Personal Care Brands, LLC, and International Refills Company, Ltd. (“Edgewell”) sued Munchkin, Inc. (“Munchkin”) in the United States District Court for the Central District of California (“the district court”) for infringement of claims of the ’420 patent and ’029 patent.

Edgewell manufactures and sells the Diaper Genie, which is a diaper pail system that has two main components: (i) a pail for collection of soiled diapers; and (ii) a replaceable cassette that is placed inside the pail and forms a wrapper around the soiled diapers.

Edgewell accused Second and Third Generation refill cassettes, which Munchkin marketed as being compatible with Edgewell’s Diaper Genie-branded diaper pails.

After the district court issued a claim construction order, construing terms of both the ’420 patent and the ’029 patent, Edgewell continued to assert literal infringement for the ’420 patent, and infringement under the doctrine of equivalents (“the DoE”) for the ’029 patent. Munchkin moved for, and the district court granted, summary judgment of noninfringement of both patents. Edgewell appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) unanimously vacated the summary judgment of noninfringement (literal infringement) of the ’420 patent, reversed the summary judgment of noninfringement (infringement under the DoE) of the ’029 patent, and remanded the case to the district court for further proceedings.

(i) The ’420 Patent

There was no dispute that the cassette itself contained a clearance when it is not installed in the pail. Rather, the dispute focused on whether the claims required a clearance space between the annular wall defining the chamfer clearance and the pail itself when the cassette was installed (emphasis added). The district court determined that “clearance” required space after cassette installation and construed the clearance as “the space around [interfering] members that remains (if there is any), not the space where the interfering member or cassette is itself located upon insertion” (emphasis added).

The Court held that the district court erred in construing the term “clearance” in a manner dependent on the way the claimed cassette is put to use in an unclaimed structure, and vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’420 patent.

On the merits, the Court stated that it is usually improper to construe non-functional claim terms in apparatus claims in a way that makes infringement or validity turn on the way an apparatus is later put to use because an apparatus claim is generally to be construed according to what the apparatus is, not what the apparatus does.

The Court moved on to argue that, absent an express limitation to the contrary, the term “clearance” should be construed as covering all uses of the claimed cassette as the parties do not dispute that the ’420 patent claims are directed only to a cassette. The Court looked into the specification to find that, in nearly all of the disclosed embodiments, the specification suggests that the cassette clearance mates with a complimentary structure in the pail such that there is “engagement” (emphasis added). Thus, the Court concluded that the claim does not require a clearance after insertion. In other words, the specification, taken as a whole, does not support the district court’s construction which would preclude such engagement when the cassette is inserted into the pail (emphasis added).

In conclusion, the Court vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’420 patent and remanded the case because the Court held that the district court erred in its construction of the term “clearance.”

(ii) The ’029 Patent

The district court construed “annular cover” in the ’029 patent as “a single, ring-shaped cover, including at least a top portion and an inner portion that are parts of the same structure” (emphasis added). Edgewell did not dispute the construction. Instead, Edgewell sought infringement under the DoE for the ’029 patent because Munchkin’s accused Second and Third Generation cassettes each include a two-part annular cover (emphasis added). The district court granted summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’029 patent under the DoE. because the district court determined that no reasonable jury could find that Munchkin’s Second and Third Generation Cassettes satisfy the ’029 patent’s “annular cover” and “tear-off section” limitations under the DoE given that favorable application of the DoE would effectively vitiate the ‘tear-off section’ limitation (emphasis added).

The Court affirmed the district court’s claim construction in view of the plain language of the claims and the written description of the ’029 patent.

In contrast, the Court disagreed to the district court’s vitiation theory under the DoE. While the Court reconfirmed the vitiation theory by stating that vitiation has its clearest application “where the accused device contain[s] the antithesis of the claimed structure”(citing Planet Bingo, LLC v. GameTech Int’l, Inc., 472 F.3d 1338, 1345 (Fed. Cir. 2006)), the Court cautioned that “[c]ourts should be cautious not to shortcut this inquiry by identifying a ‘binary’ choice in which an element is either present or ‘not present’” (citing Deere & Co. v. Bush Hog, LLC, 703 F.3d 1356–57 (Fed. Cir. 2012)).

Applying these concepts to the facts of this case, the Court conclude that the district court erred in evaluating this element as a binary choice between a single-component structure and a multi-component structure, rather than evaluating the evidence to determine whether a reasonable juror could find that the accused products perform substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, achieving substantially the same result as the claims.

Citing Edgewell’s expert testimony, the Court concluded that the detailed application of the function-way-result test, supported by deposition testimony from Munchkin employees, is sufficient to create a genuine issue of material fact for the jury to resolve and, therefore, is sufficient to preclude summary judgment of noninfringement under the DoE.

In conclusion, the Court reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’029 patent under the DoE and remanded the case.

Takeaway

· Claim construction: A term in a claim should be construed as covering all uses of the claimed subject matter.

· Infringement under the DoE: Proof of vitiation requires more than identifying a binary choice in which an element is either “present” or “not present.” Instead, the proof still requires failure of passing the function-way-result test.

Tags: claim construction > doctrine of equivalents > summary judgment > vitiation

District court’s construction of a toothbrush claim gets flossed

| January 14, 2021

Maxill Inc. v. Loops, LLC (non-precedential)

December 31, 2020

Before Moore, Bryson, and Chen (Opinion by Chen).

Summary

Construing a claim reciting an assembly of identifiably separate components, the Federal Circuit determines that a limitation associated with a claimed component pertains to the component before it is combined with the other components. The lower court’s summary judgment of non-infringement, based on a claim construction requiring assembly, is reversed.

Details

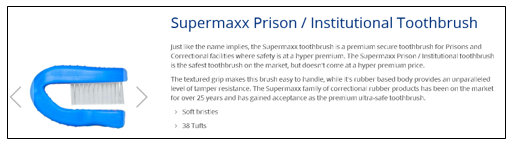

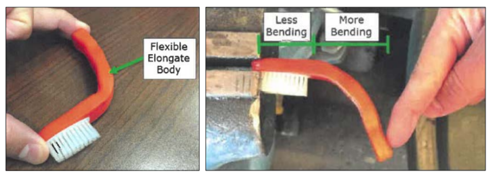

Loops, LLC and Loops Flexbrush, LLC (“Loops”) own U.S. Patent No. 8,448,285. The 285 patent is directed to a flexible toothbrush that is safe for distribution in correctional and mental health facilities. The toothbrush being made of flexible elastomers is less likely to be fashioned into a shiv.

Claim 1 of the 285 patent is representative and is reproduced below:

A toothbrush, comprising:

an elongated body being flexible throughout the elongated body and comprising a first material and having a head portion and a handle portion;

a head comprising a second material, wherein the head is disposed in and molded to the head portion of the elongated body; and

a plurality of bristles extending from the head forming a bristle brush,

wherein the first material is less rigid than the second material.

Maxill, Inc. makes “Supermaxx Prison/Institutional” toothbrushes that have a rubber-based, flexible body.

Loops and Maxill have for years been embroiled in patent infringement litigation, both in the U.S. and abroad, over flexible toothbrushes. This appeal arose out of a district court declaratory judgment action initiated by Maxill, who sought declaratory judgment of non-infringement and invalidity of the 285 patent.

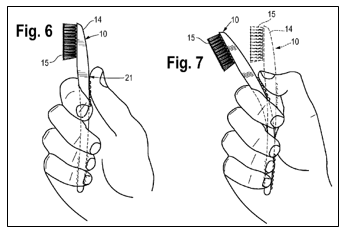

During the district court proceeding, Loops moved for summary judgment of infringement. In their opposition, Maxill argued that whereas the “flexible throughout” limitation in the 285 patent claims required that the body of the toothbrush be flexible from one end to the other, only the handle portion of the body of the Supermaxx toothbrush was flexible. The head portion of the toothbrush body, including the head, did not bend.

The district court agreed with Maxill, finding that Maxill’s Supermaxx toothbrush did not satisfy the “flexible throughout” limitation because the head portion of the toothbrush body, combined with the head, was rigid and unbendable. The district court then took the rare step of sua sponte granting Maxill summary judgment of non-infringement.

Loops appealed.

The main issue on appeal is the proper construction of the “flexible throughout” limitation. The question, however, is not simply whether the claim limitation requires that the body be flexible from one end to the other, but rather, whether the body must be flexible from one end to the other once assembled with the head.

As noted above, claim 1 of the 285 patent requires “an elongated body being flexible throughout the elongated body…and having a head portion and a handle portion”, and “a head…is disposed in and molded to the head portion of the elongated body”.

Does the “flexible throughout” limitation apply to the elongated body when it is combined with the head (i.e., post-assembly)? In that case, the district court was correct and Maxill’s Supermaxx toothbrush would not infringe the 285 patent.

Or does the “flexible throughout” limitation apply to the elongated body alone (i.e., pre-assembly)? In that case, the district court was wrong and Maxill’s Supermaxx toothbrush would be potentially infringing.

The Federal Circuit disagrees with the district court, determining that the “flexible throughout” limitation pertains to the elongated body alone and does not extend to the head even when the head is molded to the elongated body.

The Federal Circuit first looks at the claims, finding that the claims do not describe the head “as being a part of the elongated body; rather, the head…is identified in the claim as a separate element from the elongated body”.

Even though the claims require that the head be “disposed in and molded to” the elongated body, this recitation “does not meant that the head loses its identity as a separately identifiable component of the claimed toothbrush and somehow merges into becoming a part of the elongated body”,

The Federal Circuit then looks at the specification, finding that the specification consistently describes the head and elongated body as separate components.

Finally, the Federal Circuit finds that the prosecution history does not contain any “disclaimer requiring that the head be considered in evaluating the flexibility of the elongated body”.

The Federal Circuit is also bothered by the district court’s sua sponte summary judgment of non-infringement. This sua sponte action, says the Federal Circuit, deprived Loop of a full and fair opportunity to respond to Maxill’s non-infringement positions.

This case is interesting because the patentee seems to have accomplished a lot with (intentionally?) imprecise claim drafting. While the specification describes that the elongated body, as a standalone component, is fully flexible, there is no description that once combined with the head, the head portion of the elongated body remains flexible. But if the claims are construed the way the Federal Circuit has, written description or enablement is not an issue. And during prosecution, the patentee was able to distinguish over prior art teaching partially flexible toothbrush handles by arguing that the claimed elongated body was flexible throughout, but also distinguish over prior art disclosing toothbrushes with fully flexible handles and removable heads by arguing that the “permanent disposition of the head in the head portion is paramount in providing a fully flexible toothbrush while also providing the rigidity required in the head to effectively brush teeth”.

Takeaway

- Claim elements tend to be construed as identifiably separate components in the absence of claim language or descriptions in the specification indicating that the components are formed as a unitary whole. Take care when amending claims to add features that may exist only when the components are assembled or disassembled.

Dependent Claims Cannot Broaden an Independent Claim from Which They Depend

| December 4, 2020

Network-1 Technologies, Inc. v. Hewlett-Packard Company, Hewlett-Packard Enterprise Company

Before PROST, Chief Judge, NEWMAN and BRYSON, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed, in part, and affirmed, in part, the district court’s decision and ordered a new trial on infringement. Because the district court erred in construing one patent claim, the Federal Circuit concluded that the district court’s erroneous claim construction established prejudice towards Network-1. The Federal Circuit also affirmed the district court’s judgment that the dependent claims did not improperly broaden one of the asserted claims.

Background

Network-1 Technologies, Inc. (“Network-1”) owns U.S. Patent 6,218,930 (the ‘930 patent), entitled “Apparatus and Method for Remotely Powering Access Equipment over a 10/100 Switched Ethernet Network,” which sued Hewlett-Packard (“HP”) for infringement in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. The jury found the patent not infringed and invalid. But the district court granted Network-1’s motion for judgment as a matter of law (“JMOL”) on validity following post-trial motions.

Network-1 appealed the district court’s final judgment that HP does not infringe the ’930 patent, arguing the district court erred in its claim construction on “low level current” and “main power source.” HP cross-appealed the district court’s estoppel determination in raising certain validity challenges under 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2) based on HP’s joinder to an inter partes review (“IPR”) before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“the Board”). Also, HP argued that Network-1 improperly broadened claim 6 of the ’930 patent by adding two dependent claims 15 and 16.

Discussion

The ’930 patent discloses an apparatus and methods for allowing electronic devices to automatically determine if remote equipment is capable of accepting remote power over Ethernet. On appeal, the arguments on the alleged infringement are drawn towards claim 6 as follows.

6. Method for remotely powering access equipment in a data network, comprising,

providing a data node adapted for data switching, an access device adapted for data transmission, at least one data signaling pair connected between the data node and the access device and arranged to transmit data therebetween, a main power source connected to supply power to the data node, and a secondary power source arranged to supply power from the data node via said data signaling pair to the access device,

delivering a low level current from said main power source to the access device over said data signaling pair,

sensing a voltage level on the data signaling pair in response to the low level current, and

controlling power supplied by said secondary power source to said access device in response to a preselected condition of said voltage level.

Network-1 argued that the district court erroneously construed the claim terms “low level current” and “main power source” in claim 6. About “low level current,” the district court imposed both an upper bound (the current level cannot be sufficient to sustain start up) … and a lower bound (the current level must be sufficient to begin startup). Network-1 admitted that the term “low level current” describes current that cannot “sustain start up” but disagreed with the district court’s construction that the current has a lower bound at a level sufficient to begin start up.

The Federal Circuit reviewed the arguments and made it clear that “[T]he claims themselves provide substantial guidance as to the meaning of particular claim terms” and “the specification is the single best guide to the meaning of a disputed term.” It has been pointed out that the claim phrase is not limited to the word “low,” and the claim construction analysis should not end just because one reference point has been identified. The Federal Circuit further explained that the claim phrase “low level current” does not preclude a lower bound by using the word “low.” Rather, in the same way the phrase should be construed to give meaning to the term “low,” the phrase must also be construed to give meaning to the term “current.” The term “current” necessarily requires some flow of electric charge because “[i]f there is no flow, there is no ‘current.’” Therefore, the Federal Circuit confirms that the district court correctly construed the phrase “low level current.”

However, the Federal Circuit held that the district court erred in its construction of “main power source” in the patent claims resulting in prejudice towards Network-1. The district court construed “main power source” as “a DC power source,” thereby excluding AC power sources from its construction. The Federal Circuit concluded that the correct construction of “main power source” includes both AC and DC power sources. Although HP argued that the erroneous claim construction was harmless and no accused product meets the claim limitation “delivering a low level current from said main power source,” the Federal Circuit confirmed that Network-1 has established that the claim construction prejudiced it because the evidence shows that HP relied on the district court’s erroneous construction for its argument. The district court’s erroneous claim construction of “main power source” is entitled Network-1 to a new trial on infringement.

On cross-appeal, HP argued that the district court erred in concluding that HP was statutorily estopped from raising certain invalidity. In this case, HP did not petition for IPR but relied on the joinder exception to the time bar under § 315(b). HP first filed a motion to join the Avaya IPR with a petition requesting review based on grounds not already instituted. The Board correctly denied HP’s first request but later granted HP’s second joinder request, which petitioned for only the two grounds already instituted. The Federal Circuit reasoned that “HP, however, was not estopped from raising other invalidity challenges against those claims because, as a joining party, HP could not have raised with its joinder any additional invalidity challenges.” A party is only estopped from challenging claims in the final written decision based on the grounds that it “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the inter partes review (IPR). Hence, the Federal Circuit ruled that HP was not statutorily estopped from challenging the asserted claims of the ’930 patent, which were not raised in the IPR and could not have reasonably been raised by HP.

Prior to reexamination, claim 6 of the ’930 patent was construed to require the “secondary power source” to be physically separate from the “main power source.” But during the reexamination, Network-1 added claims 15 and 16, which depended from claim 6 and respectively added the limitations that the secondary power source “is the same source of power” and “is the same physical device” as the main power source. HP argued that claim 6 and the other asserted claims are invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 305 because Network-1 improperly broadened claim 6 by adding claim 15 and 16 in the reexamination. However, the Federal Circuit does not agree that claim 6 is invalid for improper broadening based on the addition of claims 15 and 16. First, a patentee is not permitted to enlarge the scope of a patent claim during reexamination. The broadening inquiry involves two steps: (1) analyzing the scope of the claim prior to reexamination and (2) comparing it with the scope of the claim subsequent to reexamination. The Federal Circuit’s broadening inquiry begins and ends with claim 6. Because claim 6 was not itself amended, the scope of claim 6 was not changed as a result of the reexamination. Where the scope of claim 6 has not changed, there has not been improper claim broadening. Dependent claims cannot broaden an independent claim from which they depend. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s conclusion that claim 6 and the other asserted claims are not invalid due to improper claim broadening.

Takeaway

- A party is only estopped from challenging claims in the final written decision based on grounds that it “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the inter partes review (IPR).

- Dependent claims cannot broaden an independent claim from which they depend.

Disavowal – Construing an element in a patent claim to require what is not recited in the claim but is described in an embodiment of the specification

| January 14, 2020

Techtronic Industries Co. Ltd. v. International Trade Commission

December 12, 2019

Lourie, Dyk, and Wallach, Circuit Judges. Court opinion by Lourie.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the Commission’s claim construction order reversing the ALJ’s construction of the term “wall console” in each of claims in the patent in suit, holding that the ALJ properly construed the term “wall console” as “wall-mounted control unit including a passive infrared detector” because each section of the specification evinces that the patent disavowed coverage of wall consoles lacking a passive infrared detector. Consequently, the Court reversed the Commission’s determination of infringement as well because the parties agreed that the appellants do not infringe the patent under the ALJ’s claim construction.

Details

I. background

1. The Patent in Suit – U.S. Patent 7,161,319 (the “‘319 patent”)

Intervenor Chamberlain Group Inc. (“Chamberlain”) owns the ‘319 patent, which discloses improved “movable barrier operators,” such as garage door openers. Claim 1, a representative claim, reads as follows:

1. An improved garage door opener comprising

a motor drive unit for opening and closing a garage door, said motor drive unit having a microcontroller

and a wall console, said wall console having a microcontroller,

said microcontroller of said motor drive unit being connected to the microcontroller of the wall console by means of a digital data bus.

2. Prior Proceedings

In July 2016, Chamberlain filed a complaint at the Commission, alleging that Techtronic Industries Co. Ltd. and others (collectively, “Appellants”) violated Section 337(a)(1)(B) of the Tariff Act of 1930 by the “importation into the United States, the sale for importation, and the sale within the United States after importation” of Ryobi Garage Door Opener models that infringe the ‘319 patent.

The only disputed term of the ‘319 patent was “wall console.” The ALJ concluded that Chamberlain had disavowed wall consoles lacking a passive infrared detector because the ‘319 patent sets forth its invention as a passive infrared detector superior to those of the prior art by virtue of its location in the wall console, rather than in the head unit, and that the only embodiment in the ‘319 patent places the passive infrared detector in the wall console as well.

The Commission reviewed the ALJ’s order and issued a decision reversing the ALJ’s construction of “wall console” and vacating his initial determination of non-infringement. The Commission presented following reasons for the reversal: (i) while “the [‘319] specification describes the ‘principal aspect of the present invention’ as providing an improved [passive infrared detector] for a garage door operator,” the specification discloses other aspects of the invention, and a patentee is not required to recite in each claim all features described as important in the written description; (ii) the claims of U.S. Patent 6,737,968, which issued from a parent application, expressly located the passive infrared detector in the wall console, “demonstrat[ing] the patentee’s intent to claim wall control units with and without [passive infrared detectors];” and (iii) the prosecution history of the ‘319 patent lacked “the clear prosecution history disclaimer.”

Under the Commission’s construction, the ALJ found that Appellants infringed the ‘319 patent. Accordingly, the Commission entered the Remedial Orders against the Appellants.

The appeal followed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously sided with the Appellants, concluding that Chamberlain disavowed coverage of wall consoles without a passive infrared detector because “the specification, in each of its sections, discloses as the invention a garage door opener improved by moving the passive infrared detector from the head unit to the wall console.”

The court opinion authored by Judge Lourie started scrutiny of the ‘319 specification with the background section. The court opinion found that the background section discloses that the prior art taught the use of passive infrared detectors in the head unit of the garage door opener to control the garage’s lighting, but that locating the detector in the head unit was expensive, complicated, and unreliable (emphases added). The court opinion moved on to state, [t]he ‘319 patent therefore sets out to solve the need for “a passive infrared detector for controlling illumination from a garage door operator which could be quickly and easily retrofitted to existing garage door operators with a minimum of trouble and without voiding the warranty.”

The court opinion further stated, “[t]he remaining sections of the patent—even the abstract—disclose a straightforward solution: moving the detector to the wall console” (emphasis added).

The court opinion dismissed the Commission’s argument that “[n]owhere does the ‘319 patent state that it is impossible or even infeasible to locate a passive infrared detector at some other location” by pointing out, “the entire specification focuses on enabling placement of the passive infra-red detector in the wall console, which is both responsive to the prior art deficiency the ’319 patent identifies and repeatedly set forth as the objective of the invention.”

As for the “other aspects of the invention” partially relied on by the Commission, the court opinion stated, “[t]he suggestion that the patent recites another invention—related to programming the microcontroller—in no way undermines the conclusion that the infrared detector must be on the wall unit .” More specifically, in response to Chamberlain’s and the Commission’s argument that portions of the description, particularly col. 4 l. 60–col. 7 l. 26, concern an exemplary method of programming the microcontroller to interact with the head unit by means of certain digital signaling techniques, matters not strictly related to the detector, the court opinion stated, “the entire purpose of this part of the description is to enable placement of the detector in the wall console, and it never discusses programming the microcontroller or applying digital signaling techniques for any purpose other than transmitting lighting commands from the wall console.”

Finally, the court opinion rejected the contention of Chamberlain and the Commission that the ‘319 patent’s prosecution history is inconsistent with disavowal, by stating, “there is [n]o requirement that the prosecution history reiterate the specification’s disavowal.”

In view of the above, the Court concluded that the ‘319 patent disavows wall consoles lacking a passive infrared detector. Accordingly, the Court reversed the Commission’s claim construction order and the determination of infringement.

Takeaway

· Disavowal, whether explicit or implicit, may cause a claim term to be construed narrower than an ordinary meaning of the term.

· Disavowal may be found with reference to an entire portion of the specification including an abstract and background section.

The Federal Circuit Affirms PTAB’s Obvious Determination Against German-Based Non-Practicing Entity, Papst Licensing GMBH & Co., Based on Both Issue Preclusion and Lack of Merit

| July 19, 2019

Papst Licensing GMBH & Co. v. Samsung

May 23, 2019

Dyk, Taranto, and Chen. Opinion by Taranto

Summary

German-based non-practicing entity Papst Licensing GMBH & Co. is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 9,189,437 entitled “Analog Data Generating and Processing Device Having a Multi-Use Automatic Processor.” The ‘437 patent issued in 2015 and claims priority to an original application filed in 1999 through continuation applications, and is one of a family of at least seven patents based on the same specification and/or priority that have been asserted in litigations by Papst against various entities to seek licenses. Here, Samsung successfully brought an Inter Parties Review (IPR) proceeding before the Patent & Trademark Appeal Board (PTAB) in which the PTAB held that claims of the ‘437 were invalid as obvious over prior art. Papst appealed the PTAB’s decision, and, on appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision based on both issue preclusion and obviousness.

Details

Procedural Background

German-based non-practicing entity Papst Licensing GMBH & Co. (“Papst”)

is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 9,189,437 entitled “Analog Data Generating and

Processing Device Having a Multi-Use Automatic Processor.” The ‘437 patent issued in 2015 and claims

priority to an original application filed in 1999 through continuation

applications, and is one of a family of at least seven patents based on the same

specification and/or priority that have been asserted in litigations by Papst

against various companies to seek licenses.

In response to such litigations, various combinations of companies filed

numerous petitions for Inter Partes Review (IPR) to review many claims of the

family of patents. In this case,

Samsung successfully initiated an IPR proceeding before the Patent &

Trademark Appeal Board (PTAB) in which the PTAB held that claims of the ‘437

were invalid as obvious over prior art.

Factual Background

The patent at issue on appeal is U.S. Patent No. 9,189,437 is entitled “Analog Data Generating and Processing Device Having a Multi-Use Automatic Processor.” The specification describes an interface device for communication between a data device (on one side of the interface) and a host computer (on the other). The interface device achieves high data transfer rates, without the need for a user-installed driver specific to the interface device, by using fast drivers that are already standard on the host computer for data transfer, such as a hard-drive driver. In short, the interface device sends signals to the host device that the interface device is an input/output device for which the host already has such a driver – i.e., such that the host device perceives the interface device to actually be that other input/output device.

For reference, claim 1of the ‘437 patent is shown below:

1. An analog data generating and processing de-vice (ADGPD), comprising:

an input/output (i/o) port;

a program memory;

a data storage memory;

a processor operatively interfaced with the i/o port, the program memory and the data storage memory;

wherein the processor is adapted to implement a data generation process by which analog data is acquired from each respective analog acquisition channel of a plurality of independent analog acquisition channels, the analog data from each respective channel is digitized, coupled into the processor, and is processed by the processor, and the processed and digitized analog data is stored in the data storage memory as at least one file of digitized analog data;

wherein the processor also is adapted to be involved in an automatic recognition process of a host computer in which, when the i/o port is operatively interfaced with a multi-purpose interface of the host computer, the processor executes at least one instruction set stored in the program memory and thereby causes at least one parameter identifying the analog data generating and processing device, independent of analog data source, as a digital storage device instead of an analog data generating and processing device to be automatically sent through the i/o port and to the multi-purpose interface of the computer (a) without requiring any end user to load any software onto the computer at any time and (b) without requiring any end user to interact with the computer to set up a file system in the ADGPD at any time, wherein the at least one parameter is consistent with the ADGPD being responsive to commands is-sued from a customary device driver;

wherein the at least one parameter provides information to the computer about file transfer characteristics of the ADGPD; and

wherein the processor is further adapted to be involved in an automatic file transfer process in which, when the i/o port is operatively interfaced with the multi-purpose interface of the computer, and after the at least one parameter has been sent from the i/o port to the multi-purpose interface of the computer, the processor executes at least one other instruction set stored in the program memory to thereby cause the at least one file of digitized analog data acquired from at least one of the plurality of analog acquisition channels to be transferred to the computer using the customary device driver for the digital storage device while causing the analog data generating and processing device to appear to the computer as if it were the digital storage device without requiring any user-loaded file transfer enabling software to be loaded on or in-stalled in the computer at any time.

a. The Board’s IPR Decision Related to the ‘437 Patent

Before the PTAB, the board held that the relevant claims of the ‘437 – claims 1-38 and 43-45 – were invalid as obvious over U.S. Patent No. 5,758,081 (Aytac), a publication setting forth standards for SCSI interfaces (discussed in the ‘081 patent) and “admitted” prior art described in the ‘437 patent.

The Aytac patent describes connecting a personal computer to an interface device that would in turn connect to (and switch between) various other devices, such as a scanner, fax machine, or telephone. The interface device includes the “CaTbox,” which is connected to a PC via SCSI cable, and to a telecommunications switch.

In its determination of obviousness, the Board adopted a claim construction that is central to Papst’s appeal. In particular, claim 1 of the ‘437 patent requires an automatic recognition process to occur “without requiring any end user to load any software onto the computer at any time” and an automatic file transfer process to occur “without requiring any user-loaded file transfer enabling software to be loaded on or installed in the computer at any time.”

The Board interpreted the “without requiring” limitations to mean “without requiring the end user to install or load specific drivers or software for the ADGPD beyond that included in the operating system, BIOS, or drivers for a multi-purpose interface or SCSI interface.” In adopting that construction, among those that can be required to be installed for the processes to occur, relying on the specification and claims as making clear that the invention contemplates use of SCSI drivers to carry out the processes.

The Board also rejected Papst’s contention that “the ‘without requiring’ limitations prohibit an end user from installing or loading other drivers.”

b. The Board’s IPR Decision Related to the ‘144 Patent

With respect to another U.S. Patent in Papst’s family of patents – i.e., U.S. Patent No. 8,966,144, which is based on the same specification as the ‘437 patent – the PTAB had issued a similar IPR decision, in which the same claim limitations of “without requiring …” were similarly interpreted as in the present board decision and in which the claim limitation was similarly found to be obvious over the same prior art as applied in the present board decision.

Following the PTAB decision related

to the ‘144 patent, Papst appealed the decision to the Federal Circuit. However, on the eve before oral arguments,

Papst voluntarily dismissed its appeal, whereby the PTAB’s decision related to

the ‘144 patent became final.

Discussion

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision based on both issue preclusion and obviousness.

- Issue Preclusion

The Federal Circuit explained that “[t]he Supreme Court has made clear that, under specified conditions, a tribunal’s resolution of an issue that is only one part of an ultimate legal claim can preclude the loser on that issue from later contesting, or continuing to contest, the same issue in a separate case. Thus:

subject to certain well-known exceptions, the general rule is that “[w]hen an issue of fact or law is actually litigated and determined by a valid and final judgment, and the determination is essential to the judgment, the determination is conclusive in a subsequent action between the parties, whether on the same or a different claim.”

The Federal Circuit noted that “we have held that the same is true of an IPR proceeding before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, so that the issue preclusion doctrine can apply in this court to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s decision in an IPR once it becomes final.”

The well-known exception, noted by the Federal Circuit, involved that: the court recognizes that “[i]ssue preclusion may be in-apt if ‘the amount in controversy in the first action [was] so small in relation to the amount in controversy in the second that preclusion would be plainly unfair.”

However, the Federal Circuit emphasized that that was not the case here, and, the court also emphasized that, in the ‘144 case Papst even brought the litigation through to the eve of oral argument, which highlights that that was not the case. Notably, the Federal Circuit also emphasizes that: “More generally, given the heavy burdens that Papst placed on its adversaries, the Board, and this court by waiting so long to abandon defense of the ’144 patent and ’746 patent claims, Papst’s course of action leaves it without a meaningful basis to argue for systemic efficiencies as a possible reason for an exception to issue preclusion.”

With respect to issue preclusion, the Federal Circuit explained that the Board in the ’144 patent decisionresolved the same claim construction issue in the same way as the Board in the present IPR. It characterized “the issue in dispute” as “center[ing] on whether the ‘without requiring’ limitations prohibit an end user from installing or loading other drivers.” Moreover, the Federal Circuit also explained that “the Board also ruled that use of SCSI software does not violate the ‘without requiring’ limitations, because the patent clearly showed that such software may be used,” and that “[t]hat ruling was not just materially identical to the Board’s claim construction ruling in this case; it also was essential to the Board’s ultimate determination, which depended on finding that the installation of CATSYNC, as disclosed in Aytac, was not prohibited by the ’144 patent’s “without requiring” limitation and that Aytac taught that the transfer process could be performed with SCSI software.”

Thus, the Federal Circuit held that issue preclusion applied in this case related to the ‘437 patent.

- Obviousness

On appeal, Papst presents two arguments that are addressed by the Federal Circuit First, Papst argues that the board improperly construed the limitation “without requiring” as meaning that the claimed processes can take place with SCSI software (or other multi-purpose interface soft-ware or software included in the operating system or BIOS).. Second, Papst argues that the board improperly concluded that Aytac teaches an automatic file transfer that can take place with only the SCSI drivers, without the assistance of user-added CATSYNC software.

With respect to the obviousness evaluation, the Federal Circuit found the Board’s conclusion regarding the construction of the “without requiring” limitations of the ‘437 patent to be correct based on the “ordinary meaning” of the words employed. The Federal Circuit explained that “[t]o state that a process can take place “without requiring” a particular action or component is, by the words’ ordinary meaning as confirmed in Celsis In Vitro, to state simply that the process can occur even though the action or component is not present; it is not to forbid the presence of the particular action or component.”

In addition, the Federal Circuit also agreed with the Board’s conclusion that SCSI interface software was permitted software in the claim construction because of the description in the specification of the ‘437 patent. The Federal Circuit expressed that: “The specification is decisive. Reflecting the recognition that SCSI interfaces were ‘present on most host devices or laptops’ at the time” and that “the specification explains that the invention contemplates use of SCSI software.”

Moreover, the Federal Circuit agreed that the “Board’s finding that a relevant skilled artisan would understand that the Aytac’s CaTbox can perform an automatic file transfer using SCSI without the CATSYNC software that Papst says is required, ” noting that Samsung’s expert Dr. Reynolds testified that only the SCSI protocol and the ASPI drivers are needed to transfer a file in Aytac, similar to the function of the ’437 patent.

Thus, the Federal Circuit affirmed the board’s determinations of obviousness related to the ‘437 patent.

Takeaway

When asserting patent infringement of multiple similar patents in a patent family, there is an increased risk of facing issue preclusion issues.

A comparison of an accused product to a commercial product that meets all the claim limitations for finding infringement of the claim

| April 29, 2019

TEK Global S.R.L. v. Sealant Systems International Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2019) (Prost, C.J.) (Case No. 17-2507)

March 29, 2019

Prost, Chief Judge, Dyk and Wallach, Circuit Judges. Court opinion by Chief Judge Prost.

Summary

In a precedential opinion, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s claim construction in a specific context that an asserted claim including “container connecting conduit” was not subject to 35 U.S.C 112, ¶ 6 (112(f)) because the term “conduit” recites sufficiently definite structure to avoid classification as a nonce term. The Federal Circuit also affirmed the district court’s overruling of the accused infringer’s objections to certain alleged product-to-product comparisons in the patentee’s closing argument with general guidance that, despite the maxim that to infringe a patent claim, an accused product must meet all the limitations of the claim, a comparison of the accused product to a commercial product that meets all the claim limitations may support a finding of infringement of the claim.

Details

I. background

1. Patent in Dispute

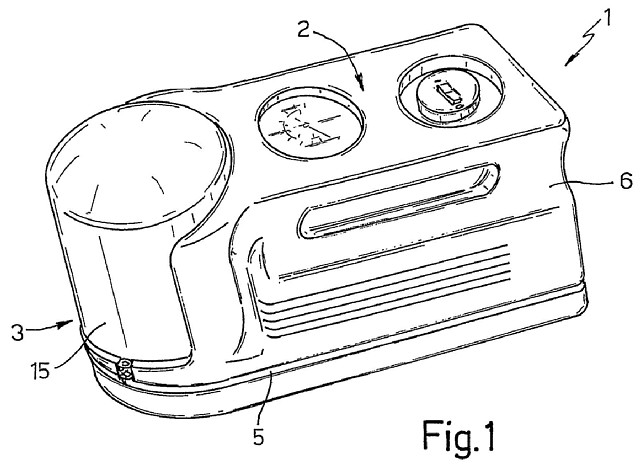

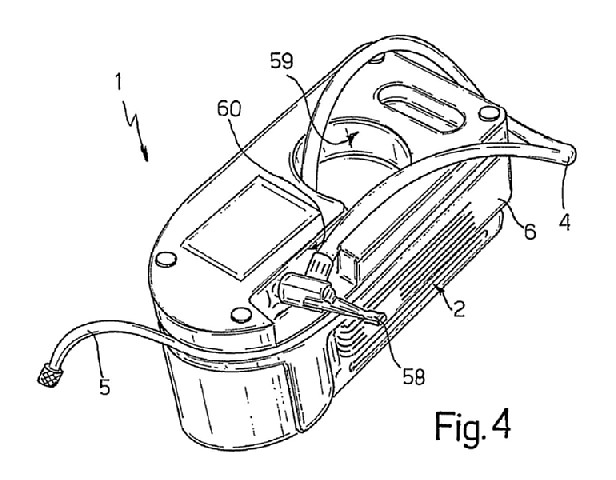

TEK Corporation and TEK Global, S.R.L. (collectively, “TEK”) owns U.S. Patent No. 7,789,110 (“’110 patent”), directed to an emergency kit for repairing vehicle tires deflated by puncture.

In a lawsuit by TEK against Sealant Systems International and ITW Global Tire Repair (collectively, “SSI”) at the United States District Court for the Northern District of California (“district court”), claim 26 is the only asserted independent claim:

26. A kit for inflating and repairing inflatable articles; the kit comprising a compressor assembly, a container of sealing liquid, and conduits connecting the container to the compressor assembly and to an inflatable article for repair or inflation, said kit further comprising an outer casing housing said compressor assembly and defining a seat for the container of sealing liquid, said container being housed removably in said seat, and additionally comprising a container connecting conduit connecting said container to said compressor assembly, so that the container, when housed in said seat, is maintained functionally connected to said compressor assembly, said kit further comprising an additional hose cooperating with said inflatable article; and a three-way valve input connected to said compressor assembly, and output connected to said container and to said additional hose to direct a stream of compressed air selectively to said container or to said additional hose.

2. Preceding Proceedings

In claim construction proceedings, SSI argued that “conduits connecting the container” and “container connecting conduit” in claim 26 are subject to 35 U.S.C. 112, ¶ 6, and that the claim requires a fast-fit coupling, which the accused product lacks.